Democracy in Georgia: Da Capo?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

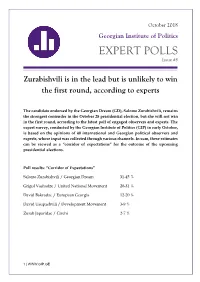

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

Letter of Concern of April 2015

7 April 2015 Mr Giorgi Margvelashvili President of Georgia Abdushelishvili st. 1, Tbilisi, Georgia1 Mr Irakli Garibashvili Prime Minister of Georgia 7 Ingorokva St, Tbilisi 0114, Georgia2 Mr David Usupashvili Chairperson of the Parliament of Georgia 26, Abashidze Street, Kutaisi, 4600 Georgia Email: [email protected] Political leaders in Georgia must stop slandering human rights NGOs Mr President, Mr Prime Minister, Mr Chairperson, We, the undersigned members and partners of the Human Rights House Network and the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders, call upon political leaders in Georgia to stop slandering non-governmental organisations with unfounded accusations and suggestions that their work would harm the country. Since October 2013, public verbal attacks against human rights organisations by leading political figures in Georgia have increased. The situation is starting to resemble to an anti-civil society campaign. In October 2013, the Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Energy Resources of Georgia, Kakhi Kaladze, criticised the non-governmental organisations, which opposed the construction of a hydroelectric power plant and used derogatory terms to express his discontent over their protest.3 In May 2014, you, Mr Prime Minister, slammed NGOs participating in the campaign about privacy rights, “This Affects You,”4 and stated that they “undermine” the functioning of the State and “damage of the international reputation of the country.”5 Such terms do not value disagreement with NGOs and their participation in public debate, but rather delegitimised their work. Further more, the Prime Minister’s statement encouraged other politicians to make critical statements about CSOs and start activities against them. -

The Relevance of the Actual Values of the Political Actors of Georgia with the Ideologies Declared by Them

The Relevance of the Actual Values of the Political Actors of Georgia with the Ideologies Declared by Them Dr. Maia Urushadze1, Dr. Tamar Kiknadze2 1Caucasus International University 2Head of the Doctoral Program in Political Science, Caucasus International University Abstract The permanent ideological impact of the propaganda narratives of powerful political entities on the international community is perceived as one of the most important challenges of the 21st century. The international agenda is full of controversial interpretations, produced by powerful international political actors. As a result, the international media agenda is getting like the battlespace for the struggle of interpretations, where the ruthless kind of "frame-games" between the strongest global agenda-setting political entities takes place. The information field is open for all countries, including the small states, where political parties are not strong enough to have their propaganda to resist the ideological pressure from outside. Due to this, the societies of these countries are still easily influenced by the narratives of global political actors creating a suitable psychological environment for internal conflicts in societies. We consider Georgia among these states. Therefore, our research aimed to study the relevance of the actual values of local (Georgian) political actors with the ideologies declared by them. In this regard, our primary objective was to understand the specifics of strategic communication of local political actors, then, to compare their narratives with the rhetoric of international actors, and finally, to determine the strength of local society's resistance to these narratives. We hope that in this way we can assess the long-term impact of global actors’ propaganda communication could have on a small country. -

Recent Elections in Georgia: at Long Last, Stability?

Recent Elections in Georgia: At long Last, Stability? DARRELL SLIDER G eorgia held its fourth contested parliamentary elections 31 October 1999 (the fifth, if one includes the 1918 multiparty elections that produced a Social Democratic government that was forced into exile by the Red Army in 1921) and its fourth presidential election on 9 April 2000. Press reports emphasized the endorsement the elections provided to President Eduard Shevardnadze and his party, the Citizens' Union of Georgia, which won a clear majority in the parlia- ment. At the same time, both the parliamentary and presidential elections were marred by heavy-handed manipulation of the political atmosphere preceding the balloting. The parliamentary elections also continued a troubling trend in Geor- gian politics: the exclusion of significant segments of the political spectrum from representation in the legislature. Perhaps more than any other former Soviet republic, Georgia has emphasized the development of political parties. Party list voting is the chief method for choosing members of parliament: lince 1992, 150 of 235 parliamentarians have been chosen by proportional voting.' The remainder, just over one-third, are cho- sen from single-member districts that correspond to Soviet-era administrative entities.2 Each election, however, has taken place under a different set of rules, which has had a major impact on the composition of the parliament. The party list system was also employed in November 1998 to choose local councils. In theory, a party list system should contribute to the formation of strong par- ties and a more stable party system. In practice, however, Georgian political par- ties remain highly personalized and organizationally weak. -

Hate Speech in Pre-Election Discourse, Presidential Elections 2018

Hate Speech in Pre-Election Discourse Presidential Elections 2018 Author: Tina Gogoladze Editor: Tamar Kintsurashvili Monitoring by Tamar Gagniashvili, Khatia Lomidze, Mariam Tskhovrebashvili, Sopo Chkhaidze Designed by Mariam Tsutskiridze The report Hate Speech in Pre-Election Discourse has been prepared by the Media Development Foundation (MDF) within the USAID-funded Promoting Integration, Tolerance and Awareness Program in Georgia (PITA), implemented by the UN Association of Georgia (UNAG). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or UNAG. 1 Methodology The present report provides the results of monitoring conducted by the Media Development Foundation (MDF) ahead of the 2018 presidential elections. The monitoring was carried out on the cases of hate speech and discrimination on various grounds expressed by electoral subjects and political parties, as well as hate speech used against presidential candidates and political parties. The report involves only the cases of discrimination on ethnic, religious, racial and gender grounds, as well as the cases of encouraging violence; it does not provide insulting comments made by political opponents against each other. The monitoring covers the period from 1 August 2018 to 15 October 2018. The subjects of monitoring were selected from both mainstream and tabloid media. The monitored subjects were: ● News and analytical programs of five TV channels: Georgian Public Broadcaster (Moambe); Rustavi 2 (Kurieri; P.S.); Imedi (Kronika; Imedis Kvira); Maestro (news program) and Obieqtivi (news program). ● Talk-shows of five TV channels: Rustavi 2 (Archevani); Imedi (Pirispir); Iberia (Tavisupali Sivrtse); Obieqtivi (Gamis Studia, Okros Kveta); Kavkasia (Barieri, Spektri). ● Seven online media outlets: Sakinformi, Netgazeti, Interpressnews, Georgia and World, PIA, Kviris Palitra, Marshalpress. -

Technical Election Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report

TECHNICAL ELECTION ASSESSMENT MISSION: GEORGIA 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION INTERIM REPORT TECHNICAL ELECTION ASSESSMENT MISSION: GEORGIA 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION INTERIM REPORT International Republican Institute IRI.org @IRI_Polls © 2020 All Rights Reserved Technical Election Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] IRI | Technical Electoral Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report 3 INTRODUCTION In June and July of 2020, the government of Georgia adopted significant constitutional and election reforms, including a modification of Georgia’s mixed electoral system and a reduction in the national proportional threshold from 5 percent to 1 percent of vote share — presenting an opportunity for citizens to pursue viable third-party options and the possibility of a new coalition government after decades of single-party domination. -

Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia's Political Development

1 The Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia’s Political Development Tbilisi 2007 2 General editing Ghia Nodia English translation Kakhaber Dvalidze Language editing John Horan © CIPDD, November 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or oth- erwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. CIPDD welcomes the utilization and dissemination of the material included in this publication. This book was published with the financial support of the regional Think Tank Fund, part of Open Society Institute Budapest. The opinions it con- tains are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect the position of the OSI. ISBN 978-99928-37-08-5 1 M. Aleksidze St., Tbilisi 0193 Georgia Tel: 334081; Fax: 334163 www.cipdd.org 3 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................ 5 Archil Abashidze .................................................................................. 8 David Aprasidze .................................................................................21 David Darchiashvili............................................................................ 33 Levan Gigineishvili ............................................................................ 50 Kakha Katsitadze ...............................................................................67 -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia March – April 2016 Detailed Methodology

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia March – April 2016 Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute. The field work was carried out by IPM Research, Ltd. • Data was collected throughout Georgia (except for the occupied territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia) between March 12 – April 2, 2016, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Georgia older than the age of 18 and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, education, region and size/type of settlement. • Multistage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday respondent selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Georgia are grouped into 10 regions plus Tbilisi city. The survey was conducted throughout all regions of Georgia, except for the occupied territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. • Stage two: The territory of each region was split into settlements, and grouped according to subtype (i.e. cities, towns and villages). • Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage three: primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus or minus 2.5 percent. • Response rate was 72%. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the U.S. -

Residents of Georgia August 4-21, 2020 Detailed Methodology

Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Georgia August 4-21, 2020 Detailed Methodology • The fieldwork was carried out by the Institute of Polling & Marketing. The survey was coordinated by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the Center for Insights in Survey Research. • Data was collected across Georgia between August 4 and August 21, 2020 through face-to-face interviews in respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Georgia aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, region and size of the settlement. • A multistage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday respondent’s selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Georgia are grouped into 10 regions. All regions of Georgia were surveyed (Tbilisi city – as separate region). • Stage two: selection of the settlements – cities and villages. • Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage three: primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus or minus 2.5 percent and the response rate was 75 percent. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. 2 Frequently Cited Disaggregates Disaggregate Disaggregation Category Base Male n=691 Gender Female n=809 Age 18-29 n=299 Age Groups Age 30-49 n=567 Age 50 and older n=635 Secondary/Incomplete secondary n=714 Education level Vocational n=223 Higher/Incomplete higher n=557 Rural n=634 Settlement type Urban (excluding Tbilisi) n=414 Tbilisi n=452 *Cited bases are weighted. -

David Usupashvili

David Usupashvili Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia David Usupashvili was elected as Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia on October 21, 2012. He has been Chairman of the Republican Party of Georgia (ALDE and LI member party) since 2005 and Deputy Chairman of the Political Coalition “Georgian Dream” since October 2011. David Usupashvili was born in Signagi, Georgia, on March 5, 1968. He graduated from Magaro Secondary School and continued education at IvaneJavakhishvili Tbilisi State University, where he obtained Diploma of Honours in Law (1985 - 1992). He received Master’s Degree in International Development Policy from Duke University, Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, USA (1997 - 1999). From 1999 to 2005 he worked for an USAID funded Rule of Law program, as Deputy Chief of Party and Senior Legal and Policy Advisor. During 2000 – 2001,David Usupashvili worked as an Executive Secretary for Anti-Corruption Working Group under President of Georgia. David Usupashvili was a founder of one of the first Georgian NGOs, Georgian Young Lawyers Associationthat promoted and largely contributed to democratization processes in Georgia. As a first Chairman he coordinated implementation of major rule of law programs (1994 - 1997). From 1992 to 1994 he worked for the President of Georgia as Senior Legal Adviser and Special Envoy of the President to Parliament and Constitutional Commission of Georgia. From 1989 to 1995 he served at the Central Election Commission of Georgia, as Chief Legal Consultant, Head of Legal Department and Member. David Usupashvili was a member of various boards of the leading Georgian NGOs such as GYLA, OSGF, TI, ISFED, ect. -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia May 20 – June 11, 2019 Detailed Methodology • The field work was carried out by Institute of Polling & Marketing. The survey was conducted by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research. • Data was collected throughout Georgia between May 20 and June 11, 2019, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ home. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Georgia aged 18 or older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, region and size of the settlement. • A multistage probability sampling method was used with random route and next-birthday respondent selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Georgia are grouped into 10 regions. All regions of Georgia were surveyed (Tbilisi city – as separate region). • Stage two: Selection of the settlements – cities and villages. • Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage three: Primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus, or minus 2.5 percent and the response rate was 68 percent. • The achieved sample is weighted for regions, gender, age, and urbanity. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the