Download [Pdf]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA November 28 – December 1 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: December 2, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Another Georgian Sent to Pretrial Custody in Occupied Tskhinvali Georgian citizen Genadi Bestaev, 51, was illegally detained by the „security committee‟ (KGB) of Russia- backed Tskhinvali Region across the line of occupation, near Khelchua village, for “illegally crossing the state border” and “illegal drug smuggling” today. According to the local agency “Res,” Tskhinvali court sentenced Bestaev, native of village Zardiantkari of Gori Municipality, to two-month pretrial custody. According to the same report, in the past, Bastaev was detained by Russia-backed Tskhinvali authorities for “similar offences” multiple times (Civil.ge, November 29, 2019). Foreign Affairs 2. Citizens of Switzerland can enter Georgia with an ID card Citizens of Switzerland can enter Georgia with an ID card, Georgian PM has already signed an official document. „Citizens of Switzerland can enter Georgia on the basis of a travel document, as well as an identity document showing a person‟s name, surname, date of birth and photo,‟ the official document reads. The resolution dated by November 28, 2019, is already in force (1TV, December 1, 2019). Internal Affairs 3. Members of European Parliament on Developments in Georgia On November 27, the European Parliament held a debate on developments in the Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries at its plenary session in Strasbourg. Kati Piri (Netherlands, Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats): “Large protests are currently held in Tbilisi since the government failed to deliver on its commitment to change the electoral code in 2020 to full proportional system. -

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

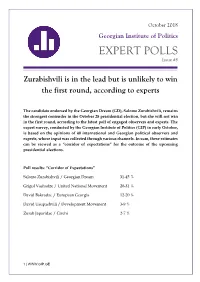

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

Presentation Kit

15YEARS PRESENTATION KIT TURKISH POLICY QUARTERLY PRESENTATION KIT MARCH 2017 QUARTERLY Table of Contents What is TPQ? ..............................................................................................................4 TPQ’s Board of Advisors ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Strong Outreach ........................................................................................................ 7 Online Blog and Debate Sections ..........................................................................8 TPQ Events ...............................................................................................................10 TPQ in the Media ..................................................................................................... 11 Support TPQ .............................................................................................................14 Premium Sponsorship ............................................................................................ 15 Print Advertising .......................................................................................................18 Premium Sponsor ...................................................................................................19 Advertiser ................................................................................................................. 20 Online Advertising ................................................................................................... 21 -

Quarterly Report on the Political Situation in Georgia and Related Foreign Malign Influence

REPORT QUARTERLY REPORT ON THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN GEORGIA AND RELATED FOREIGN MALIGN INFLUENCE 2021 EUROPEAN VALUES CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY European Values Center for Security Policy is a non-governmental, non-partisan institute defending freedom and sovereignty. We protect liberal democracy, the rule of law, and the transatlantic alliance of the Czech Republic. We help defend Europe especially from the malign influences of Russia, China, and Islamic extremists. We envision a free, safe, and prosperous Czechia within a vibrant Central Europe that is an integral part of the transatlantic community and is based on a firm alliance with the USA. Authors: David Stulík - Head of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Miranda Betchvaia - Intern of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Notice: The following report (ISSUE 3) aims to provide a brief overview of the political crisis in Georgia and its development during the period of January-March 2021. The crisis has been evolving since the parliamentary elections held on 31 October 2020. The report briefly summarizes the background context, touches upon the current political deadlock, and includes the key developments since the previous quarterly report. Responses from the third sector and Georgia’s Western partners will also be discussed. Besides, the report considers anti-Western messages and disinformation, which have contributed to Georgia’s political crisis. This report has been produced under the two-years project implemented by the Prague-based European Values Center for Security Policy in Georgia. The project is supported by the Transition Promotion Program of The Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Emerging Donors Challenge Program of the USAID. -

Georgia Between Dominant-Power Politics, Feckless Pluralism, and Democracy Christofer Berglund Uppsala University

GEORGIA BETWEEN DOMINANT-POWER POLITICS, FECKLESS PLURALISM, AND DEMOCRACY CHRISTOFER BERGLUND UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Abstract: This article charts the last decade of Georgian politics (2003-2013) through theories of semi- authoritarianism and democratization. It first dissects Saakashvili’s system of dominant-power politics, which enabled state-building reforms, yet atrophied political competition. It then analyzes the nested two-level game between incumbents and opposition in the run-up to the 2012 parliamentary elections. After detailing the verdict of Election Day, the article turns to the tense cohabitation that next pushed Georgia in the direction of feckless pluralism. The last section examines if the new ruling party is taking Georgia in the direction of democratic reforms or authoritarian closure. nder what conditions do elections in semi-authoritarian states spur Udemocratic breakthroughs?1 This is a conundrum relevant to many hybrid regimes in the region of the former Soviet Union. It is also a ques- tion of particular importance for the citizens of Georgia, who surprisingly voted out the United National Movement (UNM) and instead backed the Georgian Dream (GD), both in the October 2012 parliamentary elections and in the October 2013 presidential elections. This article aims to shed light on the dramatic, but not necessarily democratic, political changes unleashed by these events. It is, however, beneficial to first consult some of the concepts and insights that have been generated by earlier research on 1 The author is grateful to Sten Berglund, Ketevan Bolkvadze, Selt Hasön, and participants at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic-Eurasian Studies, as well as the anonymous re- viewers, for their useful feedback. -

Survey on Political Attitudes August 2020 Demographics 1. There Are A

Survey on Political Attitudes August 2020 Demographics 1. There are a number of ethnic groups living in Georgia. Which ethnic group do you consider yourself a part of? [Interviewer! Do not read. One answer only.] Armenian 1 Azerbaijani 2 Georgian 3 Other Caucasian ethnicity (Abkhazian, Lezgin, Ossetian, etc.) 4 Russian 5 Kurd or Yezidi 6 Other ethnicity 7 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 2. What is the highest level of education you have achieved to date? [Interviewer! Do not read. Correspond.] 1 Did not obtain a nine year diploma 2 Nine year diploma 3 High school diploma (11 or 12 years) 4 Vocational/technical degree 5 Bachelor’s degree/5 years diploma 6 Any degree above bachelor’s (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 3. Which of the following best describes your situation? Please tell me about the activity that you consider to be primary. [Interviewer! Read out. Only one answer that corresponds with the respondent’s main activity.] I am retired and do not work 1 I am a student and do not work 2 I am a housewife and do not work 3 I am unemployed 4 I work full or part-time, including seasonal 5 jobs I am self-employed, including seasonal jobs 6 I am disabled and cannot work 7 Other 8 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 4. How often do you use the Internet? Do you use the Internet … [READ OUT] Every day, 1 At least once a week, 2 At least once a month, 3 Less often, 4 or Never? 5 [DO NOT READ] I don’t know what the Internet is. -

Georgia 2017 Human Rights Report

GEORGIA 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The constitution provides for an executive branch that reports to the prime minister, a unicameral parliament, and a separate judiciary. The government is accountable to parliament. The president is the head of state and commander in chief. In September, a controversial constitutional amendments package that abolished direct election of the president and delayed a move to a fully proportional parliamentary election system until 2024 became law. Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) observers termed the October local elections as generally respecting fundamental freedoms and reported candidates were able to campaign freely, while highlighting flaws in the election grievance process between the first and second rounds that undermined the right to effective remedy. They noted, too, that the entire context of the elections was shaped by the dominance of the ruling party and that there were cases of pressure on voters and candidates as well as a few violent incidents. OSCE observers termed the October 2016 parliamentary elections competitive and administered in a manner that respected the rights of candidates and voters but stated that the campaign atmosphere was affected by allegations of unlawful campaigning and incidents of violence. According to the observers, election commissions and courts often did not respect the principle of transparency and the right to effective redress between the first and second rounds, which weakened confidence in the election administration. In the 2013 presidential election, OSCE observers concluded the vote “was efficiently administered, transparent and took place in an amicable and constructive environment” but noted several problems, including allegations of political pressure at the local level, inconsistent application of the election code, and limited oversight of alleged campaign finance violations. -

LETTER to G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS

LETTER TO G20, IMF, WORLD BANK, REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT BANKS and NATIONAL GOVERNMENTS We write to call for urgent action to address the global education emergency triggered by Covid-19. With over 1 billion children still out of school because of the lockdown, there is now a real and present danger that the public health crisis will create a COVID generation who lose out on schooling and whose opportunities are permanently damaged. While the more fortunate have had access to alternatives, the world’s poorest children have been locked out of learning, denied internet access, and with the loss of free school meals - once a lifeline for 300 million boys and girls – hunger has grown. An immediate concern, as we bring the lockdown to an end, is the fate of an estimated 30 million children who according to UNESCO may never return to school. For these, the world’s least advantaged children, education is often the only escape from poverty - a route that is in danger of closing. Many of these children are adolescent girls for whom being in school is the best defence against forced marriage and the best hope for a life of expanded opportunity. Many more are young children who risk being forced into exploitative and dangerous labour. And because education is linked to progress in virtually every area of human development – from child survival to maternal health, gender equality, job creation and inclusive economic growth – the education emergency will undermine the prospects for achieving all our 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and potentially set back progress on gender equity by years. -

ON the EFFECTIVE USE of PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Andrew Peek All Rights Reserved

ON THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PROXY WARFARE by Andrew Lewis Peek A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 2021 Andrew Peek All rights reserved Abstract This dissertation asks a simple question: how are states most effectively conducting proxy warfare in the modern international system? It answers this question by conducting a comparative study of the sponsorship of proxy forces. It uses process tracing to examine five cases of proxy warfare and predicts that the differentiation in support for each proxy impacts their utility. In particular, it proposes that increasing the principal-agent distance between sponsors and proxies might correlate with strategic effectiveness. That is, the less directly a proxy is supported and controlled by a sponsor, the more effective the proxy becomes. Strategic effectiveness here is conceptualized as consisting of two key parts: a proxy’s operational capability and a sponsor’s plausible deniability. These should be in inverse relation to each other: the greater and more overt a sponsor’s support is to a proxy, the more capable – better armed, better trained – its proxies should be on the battlefield. However, this close support to such proxies should also make the sponsor’s influence less deniable, and thus incur strategic costs against both it and the proxy. These costs primarily consist of external balancing by rival states, the same way such states would balance against conventional aggression. Conversely, the more deniable such support is – the more indirect and less overt – the less balancing occurs. -

Letter of Concern of April 2015

7 April 2015 Mr Giorgi Margvelashvili President of Georgia Abdushelishvili st. 1, Tbilisi, Georgia1 Mr Irakli Garibashvili Prime Minister of Georgia 7 Ingorokva St, Tbilisi 0114, Georgia2 Mr David Usupashvili Chairperson of the Parliament of Georgia 26, Abashidze Street, Kutaisi, 4600 Georgia Email: [email protected] Political leaders in Georgia must stop slandering human rights NGOs Mr President, Mr Prime Minister, Mr Chairperson, We, the undersigned members and partners of the Human Rights House Network and the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders, call upon political leaders in Georgia to stop slandering non-governmental organisations with unfounded accusations and suggestions that their work would harm the country. Since October 2013, public verbal attacks against human rights organisations by leading political figures in Georgia have increased. The situation is starting to resemble to an anti-civil society campaign. In October 2013, the Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Energy Resources of Georgia, Kakhi Kaladze, criticised the non-governmental organisations, which opposed the construction of a hydroelectric power plant and used derogatory terms to express his discontent over their protest.3 In May 2014, you, Mr Prime Minister, slammed NGOs participating in the campaign about privacy rights, “This Affects You,”4 and stated that they “undermine” the functioning of the State and “damage of the international reputation of the country.”5 Such terms do not value disagreement with NGOs and their participation in public debate, but rather delegitimised their work. Further more, the Prime Minister’s statement encouraged other politicians to make critical statements about CSOs and start activities against them. -

Bendukidze and Russian Capitalism

Georgia’s Libertarian Revolution Part two: Bendukidze and Russian Capitalism Berlin – Tbilisi – Istanbul 17 April 2010 “Bendukidze’s wealth, as compared to the assets of Russian billionaires, was relatively modest, with most estimates placing it in the range of 50 to 70 million USD in 2004. In a recent interview, he jokingly called himself a “mini-oligarch” at best. However, Kakha Bendukidze was always more than simply an investor and manager. In a 1996 ranking produced by the polling agency Vox Populi, Bendukidze was ranked 33rd among Russia’s top 50 most influential businessmen wielding the biggest influence on government economic policy. A 2004 article in Kommersant credited Bendukidze with being the first to “realise the need to create a lobbying structure that would be able to promote the interests of big business in a civilized way.” Bendukidze cared about politics and he had ideas about the way the Russian economy ought to develop.” (page 8) Table of contents 1. A biologist in Moscow ........................................................................................................ 3 2. How to Become an Oligarch ............................................................................................... 4 3. Big Business and Russian Politics ...................................................................................... 8 4. Vladimir Putin‟s authoritarian liberalism ........................................................................... 9 5. Leaving Russia (2004) ...................................................................................................... 13 Supported by The Think Tank Fund of the Open Society Institute – 3 – 1. A biologist in Moscow Kakha Bendukidze was born in Tbilisi in 1956 into a family of intellectuals. His father Avtandil was professor of mathematics at Tbilisi State University; his mother, Julietta Rukhadze, a historian and ethnographer. Bendukidze would later proudly describe a family with deep entrepreneurial roots: “My grandfather was one of the first factory owners in Georgia.