251-268 Cornell Sum 09.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

Georgia Draft Organic Laws Amending the Organic Law

Strasbourg, 19 January 2021 CDL-REF(2020)003 Opinion No. 1017 / 2021 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) GEORGIA DRAFT ORGANIC LAWS AMENDING THE ORGANIC LAW ON POLITICAL ASSOCIATIONS OF CITIZENS AMENDING THE ELECTION CODE AMENDING THE AMENDMENT TO THE ORGANIC LAW ON THE ELECTION CODE DRAFT RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE PARLIAMENT AMENDING THE RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE PARLIAMENT This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2021)003 - 2 - Draft Organic Law of Georgia Amending the Organic Law of Georgia on „Political Associations of Citizens“ Article 1. The organic law on Political Associations of Citizens (Georgia Legislation Herald, no. 45, 21.11.1997, pg. 76) is hereby amended as follows: 1. Paragraphs 4, 5 and 6 of Article 30 shall be formulated as follows: „4. A political party shall receive funding from Georgia’s state budget since the second day of acquiring full powers of relevant convocation of Parliament of Georgia until the day of acquiring full powers of next convocation of Parliament of Georgia. 5. Georgia’s state budgetary funding shall be allocated only to those political parties, which took up at least half of its mandates of Member of Parliament. If the condition forseen by this paragraph emerges, the party will stop receiving the funding from state budget from next calendar month. 6. A party shall not receive budgetary funding of relevant next 6 calendar months if more than half of the Members of Parliament elected upon nomination of this party did not attend without good reason more than half of regular plenary sittings during the previous regular plenary session of the Parliament of Georgia“; 2. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA May 13-15 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: May 16, 2019 Foreign Affairs 1. Georgia negotiating with Germany, France, Poland, Israel on legal employment Georgia is negotiating with three EU member states, Germany, France and Poland to allow for the legal employment of Georgians in those countries, as well as with Israel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia reports. An agreement has already been achieved with France. ―Legal employment of Georgians is one of the priorities for the ministry of Foreign Affairs, as such deals will decrease the number of illegal migrants and boost the qualification of Georgian nationals,‖ the Foreign Ministry says. A pilot project is underway with Poland, with up to 45 Georgian citizens legally employed, the ministry says (Agenda.ge, May 13, 2019). 2. Georgia elected as United Nations Statistical Commission member for 2020-2023 Georgia was unanimously elected as a member of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) for a period of four years, announces the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). The membership mandate will span from 2020-2023. A total of eight new members of the UNSC were elected for the same period on May 7 in New York at the meeting of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Agenda.ge, May 14, 2019). 3. President of European Commission Tusk: 10 years on there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine in EU President of the European Commission Donald Tusk stated on the 10th anniversary of the EU‘s Eastern Partnership format that there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in the EU. -

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia

Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson SILK ROAD PAPER January 2018 Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia Niklas Nilsson © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center American Foreign Policy Council, 509 C St NE, Washington D.C. Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Russian Hybrid Tactics in Georgia” is a Silk Road Paper published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and Silk Road Studies Program, Joint Center. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the American Foreign Policy Council and the Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion regarding the region. The opinions and conclusions expressed in this study are those of -

Georgia's 2008 Presidential Election

Election Observation Report: Georgia’s 2008 Presidential Elections Election Observation Report: Georgia’s saarCevno sadamkvirveblo misiis saboloo angariSi angariSi saboloo misiis sadamkvirveblo saarCevno THE IN T ERN at ION A L REPUBLIC A N INS T I T U T E 2008 wlis 5 ianvari 5 wlis 2008 saqarTvelos saprezidento arCevnebi saprezidento saqarTvelos ADV A NCING DEMOCR A CY WORLD W IDE demokratiis ganviTarebisTvis mTel msoflioSi mTel ganviTarebisTvis demokratiis GEORGI A PRESIDEN T I A L ELEC T ION JA NU A RY 5, 2008 International Republican Institute saerTaSoriso respublikuri instituti respublikuri saerTaSoriso ELEC T ION OBSERV at ION MISSION FIN A L REPOR T Georgia Presidential Election January 5, 2008 Election Observation Mission Final Report The International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 www.iri.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II. Pre-Election Period 5 A. Political Situation November 2007 – January 2008 B. Presidential Candidates in the January 5, 2008 Presidential Election C. Campaign Period III. Election Period 11 A. Pre-Election Meetings B. Election Day IV. Findings and Recommendations 15 V. Appendix 19 A. IRI Preliminary Statement on the Georgian Presidential Election B. Election Observation Delegation Members C. IRI in Georgia 2008 Georgia Presidential Election 3 I. Introduction The January 2008 election cycle marked the second presidential election conducted in Georgia since the Rose Revolution. This snap election was called by President Mikheil Saakashvili who made a decision to resign after a violent crackdown on opposition street protests in November 2007. Pursuant to the Georgian Constitution, he relinquished power to Speaker of Parliament Nino Burjanadze who became Acting President. -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

Georgia: Background and U.S

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated September 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy September 5, 2018 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest non-NATO partners among the post-Soviet states. With a history of strong economic aid and security cooperation, the United States Cory Welt has deepened its strategic partnership with Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Analyst in European Affairs Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post-Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream party has more than a three-fourths supermajority in parliament, allowing it to rule with only limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 appeared to enter a period of stronger growth than the previous four years. The Georgian Dream won elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with the former ruling party, Georgia: Basic Facts Mikheil Saakashvili’s center-right United National Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) Movement, which came to power as a result of Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. In August 2008, Capital: Tbilisi Russia went to war with Georgia to prevent Ethnic Composition: 87% Georgian, 6% Azerbaijani, 5% Saakashvili’s government from reestablishing control Armenian (2014 census) over Georgia’s regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Religion: 83% Georgian Orthodox, 11% Muslim, 3% Armenian which broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s to Apostolic (2014 census) become informal Russian protectorates. -

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION in GEORGIA 27Th October 2013

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION IN GEORGIA 27th October 2013 European Elections monitor The candidate in office, Giorgi Margvelashvili, favourite in the Presidential Election in Georgia Corinne Deloy Translated by Helen Levy On 27th October next, 3,537,249 Georgians will be electing their president of the republic. The election is important even though the constitutional reform of 2010 deprived the Head of State of some of his powers to be benefit of the Prime Minister and Parliament (Sakartvelos Parlamenti). The President of the Republic will no longer be able to dismiss the government and convene a new Analysis cabinet without parliament’s approval. The latter will also be responsible for appointing the regional governors, which previously lay within the powers of the President of the Republic. The constitutional reform which modified the powers enjoyed by the head of State was approved by the Georgian parliament on 21st March last 135 votes in support, i.e. all of the MPs present. The outgoing President, Mikheil Saakashvili (United National Movement, ENM), in office since the election on 4th January 2004 cannot run for office again since the Constitution does not allow more than two consecutive mandates. Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia in coalition with Mikheil Saakashvili. 10 have been appointed by politi- Our Georgia-Free Democrats led by former representa- cal parties, 13 by initiative groups. 54 people registe- tive of Georgia at the UN, Irakli Alasania, the Republi- red to stand in all. can Party led by Davit Usupashvili, the National Forum The candidates are as follows: led by Kakha Shartava, the Conservative Party led by Zviad Dzidziguri and Industry will save Georgia led by – Giorgi Margvelashvili (Georgian Dream-Democratic Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili has been in office Georgia), former Minister of Education and Science and since the general elections on 1st October 2012. -

D) South Caucasus

International Alert. Local Business, Local Peace: the Peacebuilding Potential of the Domestic Private Sector Case study South Caucasus* * This document is an extract from Local Business, Local Peace: the Peacebuilding Potential of the Domestic Private Sector, published in 2006 by the UK-based peacebuilding NGO International Alert. Full citation should be provided in any referencing. © International Alert, 2006. All rights reserved. No part of this publication, including electronic materials, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without full attribution. South Caucasus Between pragmatism and idealism: businesses coping with conflict in the South Caucasus Natalia Mirimanova This report explores the role that local private sector activity can play in addressing the conflicts of the South Caucasus. It is based on qualitative interviews conducted with a range of entrepreneurs, both formal and informal, carried out in 2005. It embraces three unresolved conflicts: the conflict between Armenians and Azeris over Nagorny-Karabakh; and the conflicts over Abkhazia and South Ossetia that challenged Georgia’s territorial integrity.1 All three resulted from the break-up of the Soviet Union. Despite its peaceful dissolution, the newly independent states in the South Caucasus all experienced some degree of violence. The turmoil in Georgia was linked to the escalation of internal conflicts with the autonomous regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, while the unilateral secession of Nagorny-Karabakh – a predominantly Armenian region in Azerbaijan – sparked a war between the latter and Armenia. An overview of the conflicts is provided below, together with an outline of the current political context and the private sectors. -

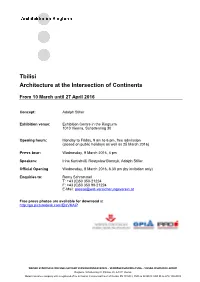

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents From 10 March until 27 April 2016 Concept: Adolph Stiller Exhibition venue: Exhibition Centre in the Ringturm 1010 Vienna, Schottenring 30 Opening hours: Monday to Friday, 9 am to 6 pm, free admission (closed on public holidays as well as 25 March 2016) Press tour: Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 4 pm Speakers: Irina Kurtishvili, Rostyslaw Bortnyk, Adolph Stiller Official Opening Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 6.30 pm (by invitation only) Enquiries to: Romy Schrammel T: +43 (0)50 350-21224 F: +43 (0)50 350 99-21224 E-Mail: [email protected] Free press photos are available for download at http://go.picturedesk.com/ElaVKAiP WIENER STÄDTISCHE WECHSELSEITIGER VERSICHERUNGSVEREIN – VERMÖGENSVERWALTUNG – VIENNA INSURANCE GROUP Ringturm, Schottenring 30, PO Box 80, A-1011 Vienna Mutual insurance company with a registered office in Vienna; Commercial Court of Vienna; FN 101530 i; DVR no 0688533; VAD ID no ATU 15363309 Tbilisi – architecture at the crossroads of Europe and Asia The name Tbilisi is derived from the old Georgian word “tbili”, which roughly translates as “warm” and refers to the region’s numerous hot sulphur springs that reach temperatures of up to 47°C. The area was first settled in the early Bronze Age, and ancient times also left their mark: in Greek mythology, the Argonauts sailed to Colchis, which was part of Georgia, in their quest for the Golden Fleece. In the fifth century King Vakhtang I Gorgasali turned the existing settlement into a fortified town, and in the first half of that century Tbilisi was recognised as the second capital of the kings of Kartli in eastern Georgia. -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Georgia – Researched and Compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 19 November 2009

Georgia – Researched and compiled by the Refugee Documentation Centre of Ireland on 19 November 2009 Information on corruption among officials in Georgia A report by the US Department of State under the heading ‘Arrest and Detention’ states: “In September 2007, former defense minister Irakli Okruashvili gave a televised press conference in which he declared his opposition to the government and accused President Saakashvili of several serious crimes, including ordering him to kill prominent businessman Badri Patarkatsishvili. Police arrested Okruashvili and charged him with corruption later that month. Opposition leaders expressed concern that Okruashvili's arrest was politically motivated, constituted an attempt to intimidate the political opposition, and was part of a series of attacks on human rights by the government. Okruashvili was released on bail in October 2007 after making a videotaped confession to some of the charges against him and retracted his charges against Saakashvili. Okruashvili left the country in November 2007 and, in subsequent interviews from abroad, stated that his confession, retraction, and departure from the country had been forced. In November 2007, Okruashvili was arrested in Germany, and later returned to France, his original entry point into Europe. On March 28, Okruashvili was tried in absentia in Tbilisi, found guilty of large-scale extortion, and sentenced to 11 years in prison. On April 23, he was granted political asylum in France. On September 12, the French appellate court ruled against Okruashvili's extradition to Georgia. During the year members of Okruashvili's political party alleged that close associates or family members of associates were arrested for their party affiliation.” (US Department of State (25th February 2009) 2008 Human Rights Report: Georgia) This report also states under the heading ‘Denial of Fair Public Trial’: “In June 2007, in cooperation with the Council of Europe, the High School of Justice established a curriculum for training judges.