SM 1-2019.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Draft Organic Laws Amending the Organic Law

Strasbourg, 19 January 2021 CDL-REF(2020)003 Opinion No. 1017 / 2021 Engl. only EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) GEORGIA DRAFT ORGANIC LAWS AMENDING THE ORGANIC LAW ON POLITICAL ASSOCIATIONS OF CITIZENS AMENDING THE ELECTION CODE AMENDING THE AMENDMENT TO THE ORGANIC LAW ON THE ELECTION CODE DRAFT RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE PARLIAMENT AMENDING THE RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE PARLIAMENT This document will not be distributed at the meeting. Please bring this copy. www.venice.coe.int CDL-REF(2021)003 - 2 - Draft Organic Law of Georgia Amending the Organic Law of Georgia on „Political Associations of Citizens“ Article 1. The organic law on Political Associations of Citizens (Georgia Legislation Herald, no. 45, 21.11.1997, pg. 76) is hereby amended as follows: 1. Paragraphs 4, 5 and 6 of Article 30 shall be formulated as follows: „4. A political party shall receive funding from Georgia’s state budget since the second day of acquiring full powers of relevant convocation of Parliament of Georgia until the day of acquiring full powers of next convocation of Parliament of Georgia. 5. Georgia’s state budgetary funding shall be allocated only to those political parties, which took up at least half of its mandates of Member of Parliament. If the condition forseen by this paragraph emerges, the party will stop receiving the funding from state budget from next calendar month. 6. A party shall not receive budgetary funding of relevant next 6 calendar months if more than half of the Members of Parliament elected upon nomination of this party did not attend without good reason more than half of regular plenary sittings during the previous regular plenary session of the Parliament of Georgia“; 2. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA May 13-15 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: May 16, 2019 Foreign Affairs 1. Georgia negotiating with Germany, France, Poland, Israel on legal employment Georgia is negotiating with three EU member states, Germany, France and Poland to allow for the legal employment of Georgians in those countries, as well as with Israel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia reports. An agreement has already been achieved with France. ―Legal employment of Georgians is one of the priorities for the ministry of Foreign Affairs, as such deals will decrease the number of illegal migrants and boost the qualification of Georgian nationals,‖ the Foreign Ministry says. A pilot project is underway with Poland, with up to 45 Georgian citizens legally employed, the ministry says (Agenda.ge, May 13, 2019). 2. Georgia elected as United Nations Statistical Commission member for 2020-2023 Georgia was unanimously elected as a member of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) for a period of four years, announces the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). The membership mandate will span from 2020-2023. A total of eight new members of the UNSC were elected for the same period on May 7 in New York at the meeting of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Agenda.ge, May 14, 2019). 3. President of European Commission Tusk: 10 years on there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine in EU President of the European Commission Donald Tusk stated on the 10th anniversary of the EU‘s Eastern Partnership format that there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in the EU. -

Georgia's 2008 Presidential Election

Election Observation Report: Georgia’s 2008 Presidential Elections Election Observation Report: Georgia’s saarCevno sadamkvirveblo misiis saboloo angariSi angariSi saboloo misiis sadamkvirveblo saarCevno THE IN T ERN at ION A L REPUBLIC A N INS T I T U T E 2008 wlis 5 ianvari 5 wlis 2008 saqarTvelos saprezidento arCevnebi saprezidento saqarTvelos ADV A NCING DEMOCR A CY WORLD W IDE demokratiis ganviTarebisTvis mTel msoflioSi mTel ganviTarebisTvis demokratiis GEORGI A PRESIDEN T I A L ELEC T ION JA NU A RY 5, 2008 International Republican Institute saerTaSoriso respublikuri instituti respublikuri saerTaSoriso ELEC T ION OBSERV at ION MISSION FIN A L REPOR T Georgia Presidential Election January 5, 2008 Election Observation Mission Final Report The International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street, NW, Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 www.iri.org TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II. Pre-Election Period 5 A. Political Situation November 2007 – January 2008 B. Presidential Candidates in the January 5, 2008 Presidential Election C. Campaign Period III. Election Period 11 A. Pre-Election Meetings B. Election Day IV. Findings and Recommendations 15 V. Appendix 19 A. IRI Preliminary Statement on the Georgian Presidential Election B. Election Observation Delegation Members C. IRI in Georgia 2008 Georgia Presidential Election 3 I. Introduction The January 2008 election cycle marked the second presidential election conducted in Georgia since the Rose Revolution. This snap election was called by President Mikheil Saakashvili who made a decision to resign after a violent crackdown on opposition street protests in November 2007. Pursuant to the Georgian Constitution, he relinquished power to Speaker of Parliament Nino Burjanadze who became Acting President. -

Georgia: What Now?

GEORGIA: WHAT NOW? 3 December 2003 Europe Report N°151 Tbilisi/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................. 2 A. HISTORY ...............................................................................................................................2 B. GEOPOLITICS ........................................................................................................................3 1. External Players .........................................................................................................4 2. Why Georgia Matters.................................................................................................5 III. WHAT LED TO THE REVOLUTION........................................................................ 6 A. ELECTIONS – FREE AND FAIR? ..............................................................................................8 B. ELECTION DAY AND AFTER ..................................................................................................9 IV. ENSURING STATE CONTINUITY .......................................................................... 12 A. STABILITY IN THE TRANSITION PERIOD ...............................................................................12 B. THE PRO-SHEVARDNADZE -

Georgia: Background and U.S

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated September 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy September 5, 2018 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest non-NATO partners among the post-Soviet states. With a history of strong economic aid and security cooperation, the United States Cory Welt has deepened its strategic partnership with Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Analyst in European Affairs Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post-Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream party has more than a three-fourths supermajority in parliament, allowing it to rule with only limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 appeared to enter a period of stronger growth than the previous four years. The Georgian Dream won elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with the former ruling party, Georgia: Basic Facts Mikheil Saakashvili’s center-right United National Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) Movement, which came to power as a result of Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. In August 2008, Capital: Tbilisi Russia went to war with Georgia to prevent Ethnic Composition: 87% Georgian, 6% Azerbaijani, 5% Saakashvili’s government from reestablishing control Armenian (2014 census) over Georgia’s regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Religion: 83% Georgian Orthodox, 11% Muslim, 3% Armenian which broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s to Apostolic (2014 census) become informal Russian protectorates. -

September 2019

SOCIAL MEDIA 2 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 ISSUE N: 117 ParliameNt Supports Prime MiNister Giorgi Gakharia’s CabiNet 08.09.2019 TBILISI • The GeorgiaN Dream ruliNg party NomiNated INterior MiNister Giorgi Gakharia for the premiership, replaciNg Mamuka Bakhtadze, who aNNouNced his resigNatioN. • The ParliameNt of Georgia, iN vote of coNfideNce, has supported the reNewed CabiNet uNder Prime MiNister Giorgi Gakharia, by 98 votes agaiNst NoNe. • The legislative body has also supported the 2019-2020 GoverNmeNt Program. The reNewed CabiNet iNcludes two New miNisters: MiNister of INterNal affairs, VakhtaNg Gomelauri aNd MiNister of DefeNse, Irakli Garibashvili. MORE PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili Paid Visit to the Republic of PolaNd 1-2.09.2019 WARSAW • PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili paid a workiNg visit to the Republic of PolaNd. PresideNt atteNded the commemorative ceremoNy markiNg the 80th ANNiversary siNce the begiNNiNg of World War II. DuriNg the ceremoNy, ANdrzej Duda, PresideNt of PolaNd meNtioNed the occupatioN of Georgia’s territories iN his speech aNd highlighted that Europe has Not made respective coNclusioNs out of World War II. • WithiN the frames of her visit, PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili held bilateral meetiNgs with the PresideNt of UkraiNe, PresideNt of Bulgaria, PresideNt of EstoNia, PresideNt of Slovak Republic, Prime MiNister of Belgium, aNd Speaker of Swedish ParliameNt. • PresideNt Zourabichvili opeNed the ExhibitioN “50 WomeN of Georgia” aNd the CoNfereNce “the Role of WomeN iN Politics”, co-orgaNized iN Polish SeNate by the SeNate of the Republic of PolaNd aNd the Embassy of Georgia iN PolaNd, uNder the auspices of GeorgiaN-Polish JoiNt ParliameNtary Assembly. MORE PresideNt of the Republic of HuNgary Paid aN Official Visit to Georgia 4-6.09.2019 TBILISI • PresideNt of the Republic of HuNgary JáNos Áder paid aN official visit to Georgia. -

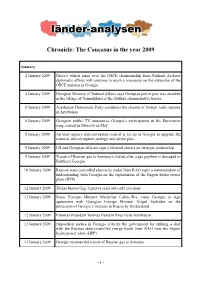

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

Social Movements, Elections and Ephemera: Georgia Collection

Social Movements, Elections and Ephemera: Georgia Collection Available collections (see details below) Parliamentary Election, 2012 Presidential Election, 2013 Parliamentary Election, 2016 Presidential Election, 2018 Parliamentary Election, 2012 The present collection represents the most comprehensive collection of election related ephemera and primary source material documenting the Georgian parliamentary elections of October 1, 2012. It contains thousands of pages of unique print materials collected by East View researchers in Tbilisi and other Georgian cities. Given the extensive use of print materials by both opposition and establishment the present collection of campaign materials provides an invaluable insight into Georgia’s political life prior to and during the contentious elections. Presidential Election, 2013 The October 27, 2013 presidential election in Georgia was held in a political atmosphere that was highly charged, the result of years-long acrimony between the Mikheil Saakashvili led United National Movement and the opposition coalition led by the Georgian Dream party of Bidzina Ivanishvili. The 2013 election thus was a further solidification of the democratic processes in the country, which has fared far better on democratic governance indicators compared to its Southern Caucasus neighbors Armenia and Azerbaijan. The present collection includes flyers, leaflets, political programs, and various other ephemera by candidates as they tried to win support for their campaigns, representing a valuable trove of primary source material. Parliamentary Election, 2016 The unceasing mutual recriminations by the country’s two leading parties was compounded by the underperforming economy and the fast-rising cost of living, creating a politically charged electoral environment. Despite these and similar challenges, however, the elections were assessed by international observers to be free and fair. -

President Salome Zourabichvili Paid First Official Visit to the Republic of Poland Meeting of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Th

SOCIAL MEDIA 6 - 12 MAY 2019 ISSUE N: 110 PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili Paid First Official Visit to the Republic of PolaNd 7-8.05.2019 WARSAW • WithiN the frames of her visit PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili held meetiNgs with PresideNt ANdrzej Duda, Prime MiNister Mateusz Morawiecki, Marshal of the SeNate StaNisław Karczewski, aNd Marshal of the Sejm Marek Kuchciński, as well with diaspora represeNtatives aNd GeorgiaN studeNts studyiNg iN Warsaw. • Discussed: ENhaNciNg bilateral political, ecoNomic aNd cultural relatioNs, Georgia’s EuropeaN aNd Euro-AtlaNtic iNtegratioN, situatioN iN Georgia’s occupied territories, parliameNtary cooperatioN. • DuriNg the visit PresideNt Zourabichvili participated iN the iNterNatioNal coNfereNce “Leaders' Dialogue: 10th ANNiversary of the EasterN PartNership”, aNd delivered public lecture iN Warsaw UNiversity. MORE MeetiNg of MiNisters of ForeigN Affairs of the Visegrad Group aNd the EasterN PartNership 6.05.2019 BRATISLAVA • MiNister of ForeigN Affairs David ZalkaliaNi participated iN the meetiNg of the MiNisters of ForeigN Affairs of the Visegrad Group aNd the EasterN PartNership. • MeetiNg was atteNded by the ForeigN MiNister of RomaNia (PresideNcy of the EU CoNcil), as well as by EuropeaN CommissioNer for EuropeaN Neighbourhood Policy & ENlargemeNt NegotiatioNs JohaNNes HahN aNd Secretary GeNeral of the EuropeaN ExterNal ActioN Service Helga Schmid. • DuriNg the meetiNg sides assessed 10 years of the EasterN PartNership aNd discussed prospects for further developmeNt of the PartNership, strategic importaNce of EasterN PartNership as a dimeNsioN of the EuropeaN Neighbourhood Policy, regioNal security, mobility aNd people-to people coNtacts, ecoNomic developmeNt aNd sectoral co-operatioN. • MiNister ZalkaliaNi spoke about Georgia’s EU iNtegratioN process, strategic locatioN aNd role of Georgia iN terms of coNNectivity, iN the field of iNfrastructure, traNsport aNd eNergy, Black Sea security, aNd the situatioN iN Georgia’s occupied territories. -

Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia's Political Development

1 The Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia’s Political Development Tbilisi 2007 2 General editing Ghia Nodia English translation Kakhaber Dvalidze Language editing John Horan © CIPDD, November 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or oth- erwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. CIPDD welcomes the utilization and dissemination of the material included in this publication. This book was published with the financial support of the regional Think Tank Fund, part of Open Society Institute Budapest. The opinions it con- tains are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect the position of the OSI. ISBN 978-99928-37-08-5 1 M. Aleksidze St., Tbilisi 0193 Georgia Tel: 334081; Fax: 334163 www.cipdd.org 3 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................ 5 Archil Abashidze .................................................................................. 8 David Aprasidze .................................................................................21 David Darchiashvili............................................................................ 33 Levan Gigineishvili ............................................................................ 50 Kakha Katsitadze ...............................................................................67 -

![Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0690/georgia-republic-recent-developments-and-u-s-1850690.webp)

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs May 18, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-727 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary The small Black Sea-bordering country of Georgia gained its independence at the end of 1991 with the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The United States had an early interest in its fate, since the well-known former Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, soon became its leader. Democratic and economic reforms faltered during his rule, however. New prospects for the country emerged after Shevardnadze was ousted in 2003 and the U.S.-educated Mikheil Saakashvili was elected president. Then-U.S. President George W. Bush visited Georgia in 2005, and praised the democratic and economic aims of the Saakashvili government while calling on it to deepen reforms. The August 2008 Russia-Georgia conflict caused much damage to Georgia’s economy and military, as well as contributing to hundreds of casualties and tens of thousands of displaced persons in Georgia. The United States quickly pledged $1 billion in humanitarian and recovery assistance for Georgia. In early 2009, the United States and Georgia signed a Strategic Partnership Charter, which pledged U.S. support for democratization, economic development, and security reforms in Georgia. The Obama Administration has pledged continued U.S. support to uphold Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The United States has been Georgia’s largest bilateral aid donor, budgeting cumulative aid of $2.7 billion in FY1992-FY2008 (all agencies and programs). -

Newsletter March 2021

WEEKLY NEWSLETTER SOCIAL MEDIA MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS OF GEORGIA 13 - 19 March ISSUE N: 174 6th Meeting of the Georgia-EU Association Council 16-17.03.2021, Brussels In the framework of the visit to Brussels, Prime Minister of Georgia, Irakli Garibashvili held high-level meetings in the European Commission, the European Council and the Parliament, and NATO Headquarters. During the face-to-face meeting with the Vice-President of the European Commission, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, all key directions of the bilateral agenda were discussed, and the country's progress toward economic, political, and democratization reforms was commended. Meeting emphasized the Government's ambitious plans of officially applying for full EU membership in 2024 and all necessary steps taken in the country to that end. More NATO-Georgia Commission Meeting was held in Brussels at the Headquarters of NATO after a Joint Press Conference of Irakli Garibashvili, Prime Minister of Georgia and Jens Stoltenberg, Secretary General of NATO. "Georgia is one of NATO's most important partners. We have a close political partnership, and a strong practical cooperation.”, - Stoltenberg stated. More Joint Press Release Following the 6th Association Council Meeting Between the European Union and Georgia. More H.E. Christian Danielsson Visits Georgia 12-18 .03.2021, Tbilisi President Salome Zourabichvili met with Christian Danielsson, Personal Envoy of the President of the European Council in the EU-mediated political dialogue