2015 Workshop Proceedings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FICHA PAÍS Francia República Francesa

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Francia República Francesa La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los medios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios, no defendiendo posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. ABRIL 2021 Moneda: euro=100 céntimos Francia Religión: La religión mayoritaria es la católica, seguida del islam. Otras re- ligiones (judaísmo, protestantismo, budismo) también están representadas, aunque en menor medida. Forma de Estado: República presidencialista, al frente de la cual está el REINO UNIDO presidente de la República, que ejerce el Poder Ejecutivo y es elegido por BÉLGICA Lille sufragio universal directo por un período de cinco años (sistema electoral a Canal de la Mancha doble vuelta). Sus poderes son muy amplios, y entre ellos se encuentra la Amiens facultad de nombrar al Primer Ministro, disolver el Parlamento y concentrar Rouen ALEMANIA Caen Metz la totalidad de los poderes en su persona en caso de crisis. El Primer Ministro PARIS Chalons-en- Champagne es el Jefe del Gobierno y debe contar con la mayoría del Parlamento; su poder Strasbourg Rennes político está muy limitado por las prerrogativas presidenciales. Orléans División administrativa: Francia se divide en 13 regiones metropolitanas, 2 regiones de ultramar y 3 colectividades únicas de ultramar, con un total de Nantes Dijon Besancon SUIZA 101 departamentos (96 metropolitanos y 5 de ultramar). -

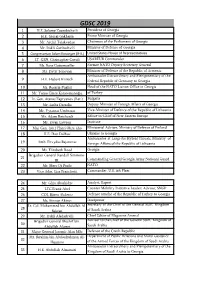

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

The Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Erkut, Gulden; Baypinar, Mete Basar Conference Paper Regional Integration in the Black Sea Region: the Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Erkut, Gulden; Baypinar, Mete Basar (2006) : Regional Integration in the Black Sea Region: the Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa, 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118385 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Focus on Ukraine September 27– October 1, 2010

Democratic initiatives foundation Focus on Ukraine September 27– October 1, 2010 1 Democratic initiatives foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS І. Overviews of political events of the week…………………….…………..…………..…3 II. Analytical Reference………………………….……………………………………...….……….5 Legislation and human rights. Ruling of the Constitutional Court: correction of mistakes or a coup d’etat?…..…………………………..…….…..…...…...…..5 Foreign policy. Ukraine-NATO relations: a period of lost opportunities?………………….….….....…..7 2 Democratic initiatives foundation І. Overviews of political events of the week Scholars and writers appealed to the President of Ukraine and the speaker of September the parliament with a request to not approve the new version of the law “On 27 Language”. They are convinced that if the law is adopted, the Russian language will be granted the status of the second official state language, which contradicts the Constitution. The organizers and participants of the the Haidamaka.UA festival of rebellious and patriotic songs held in Irpen on the outskirts of Kyiv this Sunday were assaulted by nearly two dozen youth with baseball bats. Furthermore, the local police in Irpen did not take any counteractions against the assailants. Leader of the “For Ukraine” party Vyacheslav Kyrylenko described the scuffle in Irpen an act of “political violence”. Press Secretary of the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine Yuriy Boichenko informed that the family of the former deceased Minister of Internal Affairs Yuriy Kravchenko, whom Oleksiy Pukach named the senior authority -

Conseil De L'union Européenne 31/08/2021

UNION EUROPÉENNE EU WHOISWHO ANNUAIRE OFFICIEL DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE CONSEIL DE L'UNION EUROPÉENNE 14/09/2021 Géré par l'Office des publications © Union européenne, 2021 FOP engine ver:20180220 - Content: Anninter export. Root entity 1, all languages. - X15splt1,v170601 - X15splt2,v161129 - Just set reference language to FR (version 20160818) - Removing redondancy and photo for xml for pdf(ver 20201206,execution:2021-09-14T18:54:54.042+02:00 ) - convert to any LV (version 20170103) - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem): 20210616-0 - execution of xslt to fo code: 2021-09-14T18:55:07.953+02:00- linguistic version FR - NAL countries.xml ver (if no ver it means problem):20210616-0 rootentity=CONSIL Avertissement : Les données à caractère personnel figurant dans cet annuaire sont fournies par les institutions, agences et organes de l'Union européenne. Elles sont présentées soit par ordre protocolaire, lorsqu’il existe, soit par ordre alphabétique, sauf erreur ou omission. L’utilisation de ces données à des fins de marketing direct est strictement interdite. Si vous décelez des erreurs, veuillez en faire part à: [email protected] Géré par l'Office des publications © Union européenne, 2021 La reproduction est autorisée. Toute utilisation ou reproduction des photos nécessite l’autorisation préalable des détenteurs des droits d’auteur. LISTE DES BÂTIMENTS (CODIFICATION ABRÉGÉE) Code Ville Adresse DAIL Bruxelles Crèche Conseil Avenue de la Brabançonne 100 / Brabançonnelaan 100 JL Bruxelles Justus Lipsius Rue de la Loi -

Diplomatic Corps of Ukraine Надзвичайні І Повноважні Посли України В Іноземних Державах Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to Foreign Countries

Дипломатичний корпус України Diplomatic Corps of Ukraine Надзвичайні і Повноважні Посли України в іноземних державах Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to foreign countries Відомості станом на 8 жовтня 2019 року. Можливі зміни у складі керівників дипломатичних місій будуть у наступному випуску щорічника При підготовці щорічника використано матеріали Міністерства закордонних справ України Data current as of October 8, 2019. Possible changes in composition of the heads of diplomatic missions will be provided in the next issues of the edition Data of the Ministry of Foreign Aairs of Ukraine were used for preparation of this year-book materials АВСТРАЛІЙСЬКИЙ СОЮЗ e Commonwealth of Australia Надзвичайний і Повноважний Посол Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 24.09.2015 МИКОЛА КУЛІНІЧ Mykola Kulinіch Надзвичайний Ambassador Extraordinary і Повноважний Посол and Plenipotentiary Олександр Міщенко (2004–2005); Oleksandr Mishchenko (2004–2005); Посол України в Австралії Ambassador of Ukraine та Новій Зеландії to Australia and New Zealand Валентин Адомайтіс (2007–2011); Valentyn Adomaitis (2007–2011); Тимчасові повірені у справах: Chargé d’Aaires: Сергій Білогуб (2005–2007); Serhii Bilohub (2005–2007); Станіслав Сташевський (2011–2014); Stanislav Stashevskyi (2011–2014); Микола Джиджора (2014–2015) Mykola Dzhydzhora (2014–2015) АВСТРІЙСЬКА РЕСПУБЛІКА e Republic of Austria Надзвичайний і Повноважний Посол Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 17.11.2014 ОЛЕКСАНДР ЩЕРБА Oleksandr Shcherba Надзвичайні Ambassadors -

La Lettre Janvier 2020

La Lettre Janvier 2020 www.irsem.fr VIE DE L’IRSEM (p. 1) BIBLIOTHÈQUE STRATÉGIQUE (p. 17) Équipe, Dernières publications de l’IRSEM, Le Collimateur (le podcast de l’IRSEM), Événements, Actualité du ministère, Actualité des chercheurs, Actualité des chercheurs associés VEILLE SCIENTIFIQUE (p. 16) Balkans, Sahel À VENIR (p. 18) questions régionales, adjoint au directeur), du SGDSN (sous-di- VIE DE L’IRSEM recteur chargé du contrôle des exportations d’armement, puis sous-directeur chargé des crises & conflits), de la DGA (attaché d’armement au Japon), du ministère des Affaires étrangères ÉQUIPE (consultant permanent sur l’Asie-Pacifique) et de l’université (chercheur au Centre de recherches internationales et straté- En janvier 2020, l’IRSEM accueille deux nouveaux giques de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne). arrivants, Nicolas Regaud, délégué au développement Docteur en science politique de l’Université Paris 1 international, et Dorian Léger, chargé de communication. Panthéon-Sorbonne, il a publié deux ouvrages sur la Nicolas Regaud a rejoint l’IRSEM en tant péninsule indochinoise sous l’angle stratégique et un que Délégué au développement interna- grand nombre d’articles dans des revues nationales et tional. Au sein de l’équipe de direction, internationales concernant, pour la plupart, les questions rattachée directement au directeur, cette de défense et de sécurité en Asie. nouvelle fonction consiste à développer Nouveau chargé de communication du les activités internationales de l’IRSEM, pôle valorisation de la pensée straté- notamment au travers de partenariats gique de l’équipe de soutien à la avec des centres de recherche straté- recherche, Dorian Léger est diplômé de gique homologues. -

6 February 10, 2002

INSIDE:• Ambassadors reflect on 10 years of U.S.-Ukraine relations — page 3. • A look at the sports career of Olympian Zenon Snylyk — pages 8-9. • Lviv acts to salvage its architectural monuments — page 12. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXX HE No.KRAINIAN 6 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2002 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine’sT OlympicU athletes train UndersecretaryW of State Paula Dobriansky in Sun Valley for Winter Games visits Kyiv to size up election preparations by Roman Woronowycz incidents were not a reason to condemn the Kyiv Press Bureau overall process this early on. “When allegations are put on the table, KYIV – Undersecretary of State Paula one part of the election process is that, Dobriansky used a two-day visit to Kyiv on whether founded or not, each one is investi- February 5-6 to glimpse how elections to gated thoroughly,” Dr. Dobriansky Ukraine’s Parliament are shaping up and to explained. emphasize their significance in The undersecretary of state explained Washington’s eyes. During a series of meet- that the allegations of improprieties to ings with government officials, including which she alluded were from a report issued President Leonid Kuchma, as well as law- by the respected civic organization the makers, journalists and representatives of Committee of Ukrainian Voters. civic organizations, she said that an accent The report, which is published monthly, must be placed on keeping the entire elec- is a compilation of alleged election law vio- toral process, which will culminate in a lations as reported by hundreds of monitors national poll on March 31, free and fair. -

Pour Une Véritable Politique Publique Du Renseignement Sébastien-Yves Laurent

Pour une véritable politique publique du renseignement Sébastien-Yves Laurent ÉTUDE JUILLET 2014 Pour une véritable politique publique du renseignement L’Institut Montaigne est un laboratoire d’idées - think tank - créé fin 2000 par Claude Bébéar et dirigé par Laurent Bigorgne. Il est dépourvu de toute attache partisane et ses financements, exclusivement privés, sont très diversifiés, aucune contribution n’excédant 2 % de son budget annuel. En toute indépendance, il réunit des chefs d’entreprise, des hauts fonctionnaires, des universitaires et des représentants de la société civile issus des horizons et des expériences les plus variés. Il concentre ses travaux sur quatre axes de recherche : Cohésion sociale (école primaire, enseignement supérieur, emploi des jeunes et des seniors, modernisation du dialogue social, diversité et égalité des chances, logement) Modernisation de l’action publique (réforme des retraites, justice, santé) Compétitivité (création d’entreprise, énergie pays émergents, financement des entreprises, propriété intellectuelle, transports) Finances publiques (fiscalité, protection sociale) Grâce à ses experts associés (chercheurs, praticiens) et à ses groupes de travail, l’Institut Montaigne élabore des propositions concrètes de long terme sur les grands enjeux auxquels nos sociétés sont confrontées. Il contribue ainsi aux évolutions de la conscience sociale. Ses recommandations résultent d’une méthode d’analyse et de recherche rigoureuse et critique. Elles sont ensuite promues activement auprès des décideurs publics. À travers ses publications et ses conférences, l’Institut Montaigne souhaite jouer pleinement son rôle d’acteur du débat démocratique. L’Institut Montaigne s’assure de la validité scientifique et de la qualité éditoriale des travaux qu’il publie, mais les opinions et les jugements qui y sont formulés sont exclusivement ceux de leurs auteurs. -

Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War

Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War Lyle J. Morris, Michael J. Mazarr, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Stephanie Pezard, Anika Binnendijk, Marta Kepe C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2942 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0309-4 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: Stringer China/Reuters. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The United States is entering a period of intensifying strategic compe- tition with several rivals, most notably Russia and China. -

French Intelligence Decisions and Anticipating and Assessing Risks

̸» ײ¬»´´·¹»²½»® Ö±«®²¿´ ±º ËòÍò ײ¬»´´·¹»²½» ͬ«¼·» From AFIO's The Intelligencer Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies Volume 21 • Number 2 • $15 single copy price Summer 2015 © 2015 AFIO - Association of Former The original 2008 White Paper on Defense and Intelligence Officers, All Rights Reserved National Security, confirmed by that of 2013,5 aimed ÞÛÌÎßÇßÔÍô ØßÝÕÍ ú ÐËÞÔ×Ý Ü×ÍÌÎËÍÌ at filling the gap between the country’s strategic inter- Association of Former Intelligence Officers 7700 Leesburg Pike Ste 324 ests and the capabilities of the French services to fulfill Falls Church, Virginia 22043 them. The 2008 White Paper gave them a strategic Web: www.afio.com , E-mail: [email protected] function named “Knowledge and Anticipation” and thereby propelled the services from obscurity to a cen- Guide to the Study of Intelligence tral role. According to the present head of the French foreign agency DGSE, Bernard Bajolet, intelligence is now seen as necessary in supporting national security French Intelligence decisions and anticipating and assessing risks. Some peculiarities make French intelligence by Philippe Hayez and Hedwige Regnault de Maulmin quite difficult to handle. France remains an exception within the democracies since its intelligence services are not ruled by any parliamentary law, but by a simple oday’s dialectic between transparency and règlement (regulation). Another characteristic of secrecy regarding intelligence issues, questions French intelligence is a paucity of intelligence-related Tthe very existence of secret services. Indeed, the research. French universities have not included intel- idea that government prerogatives should be hidden ligence as a field of study, with the notable exception from the citizens to serve the raison d’Etat is paradox- of Sciences Paris.6 ical in an era where transparency is encouraged and This paper provides a brief history, and outlines seen as a characteristic of an ideal democracy. -

Workshop (PDF)

proceedings of the 34th international workshop on global security Global Security in the Age of Hacking and Information Warfare Is Democracy at Stake? Mrs. Florence Parly Minister for the Armed Forces and Workshop Patron Lieutenant General Bernard de Courrèges d’Ustou Director, Institut des hautes études de défense nationale Dr. Roger Weissinger-Baylon Workshop Chairman and Founder Anne D. Baylon, LL.B., M.A. Editor Cover image Hôtel National des Invalides, Paris Published by Center for Strategic Decision Research | Strategic Decisions Press 2456 Sharon Oaks Drive, Menlo Park, California 94025 USA www.csdr.org Anne D. Baylon, LL.B., M.A., Editor | [email protected] Dr. Roger Weissinger-Baylon, Chairman | [email protected] Photography by Matteo Pellegrinuzzi | [email protected] International Standard Book Number: 1-890664-24-3 © 2017, 2018 Center for Strategic Decision Research Workshop Proceedings Anne D. Baylon, LL.B., M.A. Editor workshop Patron Mrs. Florence Parly Minister for the Armed Forces Theme Global Security in the Age of Hacking and Information Warfare Is Democracy at Stake? Workshop Chairman & Founder Dr. Roger Weissinger-Baylon Co-Director, Center for Strategic Decision Research Presented by Center for Strategic Decision Research (CSDR) and Institut des hautes études de défense nationale (IHEDN) within the French Prime Minister’s organization, including the Castex Chair of Cyber Security Principal Sponsors French Ministry of Defense United States Department of Defense Office of the Director of Net Assessment North Atlantic