The Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

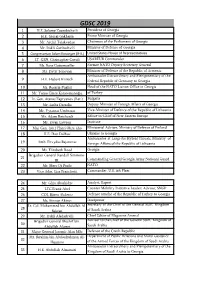

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Focus on Ukraine September 27– October 1, 2010

Democratic initiatives foundation Focus on Ukraine September 27– October 1, 2010 1 Democratic initiatives foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS І. Overviews of political events of the week…………………….…………..…………..…3 II. Analytical Reference………………………….……………………………………...….……….5 Legislation and human rights. Ruling of the Constitutional Court: correction of mistakes or a coup d’etat?…..…………………………..…….…..…...…...…..5 Foreign policy. Ukraine-NATO relations: a period of lost opportunities?………………….….….....…..7 2 Democratic initiatives foundation І. Overviews of political events of the week Scholars and writers appealed to the President of Ukraine and the speaker of September the parliament with a request to not approve the new version of the law “On 27 Language”. They are convinced that if the law is adopted, the Russian language will be granted the status of the second official state language, which contradicts the Constitution. The organizers and participants of the the Haidamaka.UA festival of rebellious and patriotic songs held in Irpen on the outskirts of Kyiv this Sunday were assaulted by nearly two dozen youth with baseball bats. Furthermore, the local police in Irpen did not take any counteractions against the assailants. Leader of the “For Ukraine” party Vyacheslav Kyrylenko described the scuffle in Irpen an act of “political violence”. Press Secretary of the Prosecutor General’s Office of Ukraine Yuriy Boichenko informed that the family of the former deceased Minister of Internal Affairs Yuriy Kravchenko, whom Oleksiy Pukach named the senior authority -

Diplomatic Corps of Ukraine Надзвичайні І Повноважні Посли України В Іноземних Державах Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to Foreign Countries

Дипломатичний корпус України Diplomatic Corps of Ukraine Надзвичайні і Повноважні Посли України в іноземних державах Ambassadors Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to foreign countries Відомості станом на 8 жовтня 2019 року. Можливі зміни у складі керівників дипломатичних місій будуть у наступному випуску щорічника При підготовці щорічника використано матеріали Міністерства закордонних справ України Data current as of October 8, 2019. Possible changes in composition of the heads of diplomatic missions will be provided in the next issues of the edition Data of the Ministry of Foreign Aairs of Ukraine were used for preparation of this year-book materials АВСТРАЛІЙСЬКИЙ СОЮЗ e Commonwealth of Australia Надзвичайний і Повноважний Посол Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 24.09.2015 МИКОЛА КУЛІНІЧ Mykola Kulinіch Надзвичайний Ambassador Extraordinary і Повноважний Посол and Plenipotentiary Олександр Міщенко (2004–2005); Oleksandr Mishchenko (2004–2005); Посол України в Австралії Ambassador of Ukraine та Новій Зеландії to Australia and New Zealand Валентин Адомайтіс (2007–2011); Valentyn Adomaitis (2007–2011); Тимчасові повірені у справах: Chargé d’Aaires: Сергій Білогуб (2005–2007); Serhii Bilohub (2005–2007); Станіслав Сташевський (2011–2014); Stanislav Stashevskyi (2011–2014); Микола Джиджора (2014–2015) Mykola Dzhydzhora (2014–2015) АВСТРІЙСЬКА РЕСПУБЛІКА e Republic of Austria Надзвичайний і Повноважний Посол Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary 17.11.2014 ОЛЕКСАНДР ЩЕРБА Oleksandr Shcherba Надзвичайні Ambassadors -

6 February 10, 2002

INSIDE:• Ambassadors reflect on 10 years of U.S.-Ukraine relations — page 3. • A look at the sports career of Olympian Zenon Snylyk — pages 8-9. • Lviv acts to salvage its architectural monuments — page 12. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXX HE No.KRAINIAN 6 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2002 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine’sT OlympicU athletes train UndersecretaryW of State Paula Dobriansky in Sun Valley for Winter Games visits Kyiv to size up election preparations by Roman Woronowycz incidents were not a reason to condemn the Kyiv Press Bureau overall process this early on. “When allegations are put on the table, KYIV – Undersecretary of State Paula one part of the election process is that, Dobriansky used a two-day visit to Kyiv on whether founded or not, each one is investi- February 5-6 to glimpse how elections to gated thoroughly,” Dr. Dobriansky Ukraine’s Parliament are shaping up and to explained. emphasize their significance in The undersecretary of state explained Washington’s eyes. During a series of meet- that the allegations of improprieties to ings with government officials, including which she alluded were from a report issued President Leonid Kuchma, as well as law- by the respected civic organization the makers, journalists and representatives of Committee of Ukrainian Voters. civic organizations, she said that an accent The report, which is published monthly, must be placed on keeping the entire elec- is a compilation of alleged election law vio- toral process, which will culminate in a lations as reported by hundreds of monitors national poll on March 31, free and fair. -

SCIENTIFIC YEARBOOK Issue Twelve

SCIENTIFIC YEARBOOK Issue Twelve Compilers Leonid Guberskiy, Pavlo Kryvonos, Borys Gumenyuk, Anatoliy Denysenko, Vasyl Turkevych Kyiv • 2011 ББК 66.49(4УКР)я5+63.3(4УКР)Оя5 UKRAYINA DYPLOMATYCHNA (Diplomatic Ukraine) SCIENTIFIC AN NUALLY Issued since November 2000 THE TWELFTH ISSUE Founders: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Diplomatic Academy at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine General Directorate for Servicing Foreign Representations Historical Club Planeta The issue is recommended for publishing by the Scientific Council of the Diplomatic Academyat the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine, Protocol No of September 28, 2011 р. Publisher: General Directorate for Servicing Foreign Representations Chief Editor Anatoliy Denysenko, PhD (history) Deputy chief editors: Borys Humenyuk, Doctor of History, Vasyl Turkevych, Honored Art Worker of Ukraine Leonid Schlyar, Doctor of Political Sciences Executive editor: Volodymyr Denysenko, Doctor of History ISBN 966-7522-07-5 EDITORIAL BOARD Kostyantyn Gryschenko, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine Leonid Guberskiy, Rector of the T.G. Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Member of the NAS of Ukraine, Doctor of Philosophy Borys Humenyuk, Rector of the Diplomatic Academy of Ukraine under the MFA of Ukraine, Deputy Chief Editor Volodymyr Khandogiy, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Ukraine to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Volodymyr Yalovyi, Deputy Head of the VR Staff of Ukraine Oleh Bilorus, Head of the VR Committee of Ukraine for Foreign -

NATO SPS Science Day in Kyiv, Ukraine, 27 May 2016

Special Edition NATO SPS Science Day in Kyiv, Ukraine, 27 May 2016 NATO Emerging Security Challenges Division Special Edition NATO SPS Science Day in Kyiv, Ukraine, 27 May 2016 — SPS Cooperation with Ukraine — NATO Emerging Security Challenges Division 4 Science for Peace and Security Cooperation with Ukraine The NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme is a partnership tool that promotes se- curity-related practical cooperation between experts and scientists from NATO and Partner countries. Active engagement between Ukraine and the SPS Programme dates back to 1991 and has been deep- ening ever since. In response to the crisis in Ukraine and following the political guidance provided by NATO Foreign Ministers in April 2014, practical co- operation with Ukraine in the field of science and technology has been further enhanced. In September 2015, the NATO-Ukraine Joint Work- ing Group on Scientific and Environmental Coop- NATO Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security eration (JWGSEC) met at NATO HQ in Brussels. Challenges, Ambassador Sorin Ducaru, and the Ambas- The high-level Ukrainian Delegation was led by the sador of Ukraine to NATO, Ihor Dolhov speak about prac- Deputy Minister of Education, Mr. Maxim Strikha. tical cooperation at a joint interview in December 2014. During the meeting, the Ukrainian representatives provided an overview of the impact of the current security crisis in Ukraine on scientific infrastructure and education institutes in the country. In this regard, the SPS Programme plays an important role by en- gaging Allied and Ukrainian scientists and experts in The NATO Science for meaningful, practical cooperation, forging networks Peace and Security and supporting capacity building in the country. -

The NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme

The Emerging Security Challenges Division The NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme CONTACT US Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme Emerging Security Challenges Division (ESCD) NATO HQ Bd. Leopold III B-1110 Brussels Belgium Fax: +32 2 707 4232 Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2016 You can find further information and the latest news about the SPS Programme on our website (www.nato.int/science). You can also follow the SPS Programme on Twitter @NATO_SPS. 1214-17 NATO GRAPHICS & PRINTING 1214-17 NATO The Emerging Security Challenges Division The NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme Annual Report 2016 1 Foreword by Ambassador Sorin Ducaru The implementation of the NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme over the last year has been pursued in close alignment with NATO’s strategic objectives and partnership priorities: SPS activities made concrete contributions to NATO’s Defence and Related Security Capacity Building (DCB) Initiative for partners and helped to project stability towards the East and South of the Alliance. Responding to the Warsaw Summit guidance, the Programme also demonstrated its flexibility and versatility as a unique tool, quickly offering valuable training modules and practical cooperation through SPS projects to partner nations. As a concrete example in this sense, the SPS Programme responded to political guidance from Allies and a request from our Iraqi partners by launching a flagship project to contribute to Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) Disposal and Search Capacity Building for Iraq. The SPS Programme is currently providing both equipment and expert training, assuming a train-the-trainer approach to harness a multiplier effect and ensure the sustainability of the training. -

2 Present-Day Challenges to Ukraine's Security

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE π 2 (106) CONTENTS 2009 PRESENT-DAY SECURITY CHALLENGES REQUIRE JOINT RESPONSES ..............................2 UKRAINE’S NATIONAL SECURITY IN THE XXI CENTURY: Founded and published by: CHALLENGES AND THE NEED FOR COLLECTIVE ACTION .......................................................3 UKRAINE’S NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY IN PRESENT-DAY CIRCUMSTANCES (Presentations by expert discussion participants) ..................................................................7 Ihor ARHUCHYNSKYI ...............................................................................................................7 UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES Viktor KORENDOVYCH .............................................................................................................8 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV Yevhen SHELEST .....................................................................................................................9 Petro KANANA .........................................................................................................................9 Director General Anatoliy Rachok Oleksandr BELOV ...................................................................................................................10 Editor-in-Chief Yevhen Shulha Valeriy CHALYI .......................................................................................................................11 Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala ..............................................................................................................12 -

Security and Nonproliferation

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL CENTER ON EXPORT AND IMPORT OF SPECIAL TECHNOLOGIES, HARDWARE AND MATERIALS SECURITY AND NONPROLIFERATION ISSUE 3 (9) 2005 KYIV 2005 SECURITY AND NONPROLIFERATION ISSUE 3 (9) 2005 Dear Reader, This issue of our journal is dedicated to an extraordinary event for the nuclear weapons non-proliferation regime - VII Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. The creators of the NPT being the basis for the non-proliferation regime factored in the need to respond to challenges and problems that form proliferation threats and established for that purpose a five-year period to consummate in a Review Conference. The main purpose of the Conference is to monitor NPT efficiency on a phased basis and follow up on the implementation of decisions made at previous Review Conferences. The previous Conference was held in 2000. The current VII Review Conference is being convened at a hard time experienced by the Treaty. New threats to the non-proliferation regime that emerged after the breakup of the bipolar world and have been growing over recent years are a quite tangible challenge to the survival of both the NPT itself, and the regime in general. One should clearly understand that a single nuclear-weapon proliferation event is able to make a crack in the dam preventing nuclear weapons from creeping throughout the planet and put the whole dam at risk of being rapidly washed out. It will result in a less stable and predictable world, in which all countries will feel less secure. North Korea’s and Iran’s problems have reached a climax of intensity. -

November 29, 2016 | Hilton Kyiv Hotel

November 29, 2016 | Hilton Kyiv Hotel Welcoming Remarks Contents 6 Security & Defense Panel How will Ukraine look in 2020? 7 Panel moderator: Welcome to the 5th annual Tiger Conference. Our theme this year Mark Hertling is “Ukraine: Vision 2020.” The nation has set many goals to achieve 7 Panel speakers: in the next three years – NATO membership, European Union inte- Pavlo Klimkin gration, a fast-growing and innovative economy, reduced corruption, Linas Antanas Linkevičius Ihor Dolhov energy independence, visa-free travel and many others. Pavel E. Felgenhauer MOHAMMAD Are Ukraine’s leaders – and its people – serious about achieving Ivanna Klympush-Tsintsadze ZAHOOR these aims? If so, what concrete steps must they take to achieve 12 Asset Recovery Panel success? What obstacles are blocking the way? Chairman of ISTIL 13 Panel moderator: Group and Kyiv Post Natalie Jaresko One clear obstacle is Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine and how publisher it transforms our society, the subject of our fi rst panel. Another is 13 Panel speakers: asset recovery – how Ukraine can recover the $40 billion stolen from Myroslava Krasnoborova Igor Budnik the people during President Viktor Yanukovych's administration. It Andriy Stelmashchuk is the focus of the second panel today. A third panel explores how Daria Kaleniuk Ukraine intends to build a new economy that works for everyone. The 16 New Economy Panel fi nal panel we call reality check, in which fi ve knowledgeable experts will give us an honest picture of where the nation stands today. 17 Panel moderator: Daniel Bilak The Tiger Conference gets better every year, thanks to our sponsors 17 Panel speakers: and all of you. -

ENGLISH Only Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe

SEC.GAL/80/05 11 April 2005 OSCE+ ENGLISH only Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic and Environmental Activities Vienna, 8 April 2005 To: All OSCE Delegations Partners for Co-operation Mediterranean Partners for Co-operation Subject: Third Preparatory Seminar for the Thirteenth OSCE Economic Forum: “Integrating Persons belonging to National Minorities: Economic and other Perspectives” Attached herewith is the Consolidated Summary of the Third Preparatory Seminar for the Thirteenth OSCE Economic Forum: “Integrating Persons belonging to National Minorities: Economic and other Perspectives”, which took place in Kyiv, Ukraine, 10-11 March 2005. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office of the Co-ordinator of OSCE Economic Vienna, 8 April 2005 and Environmental Activities CONSOLIDATED SUMMARY THIRD PREPARATORY SEMINAR FOR THE THIRTEENTH OSCE ECONOMIC FORUM: INTEGRATING PERSONS BELONGING TO NATIONAL MINORITIES: ECONOMIC AND OTHER PERSPECTIVES KYIV, UKRAINE, 10-11 MARCH 2005 OFFICE OF THE CO-ORDINATOR OF OSCE ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL ACTIVITIES KÄRNTNER RING 5-7, 7TH FLOOR, 1010 VIENNA; TEL: + 43 1 51436-0; FAX: 51436-96; EMAIL: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE SEMINAR………………………………………………………...………3 OPENING PLENARY SESSION Welcoming remarks by: • H.E. Ihor Dolhov, Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine …………………………….8 • Mr. Stanislav Raščan, Acting Director General of the Directorate for Policy Planning and Multilateral Political Relations, -

Overview of Science for Peace and Security Programme's Projects In

Overview of Science for Peace and Security Programme’s Projects in Ukraine September 2015 Contact us Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme Emerging Security Challenges Division (ESCD) NATO HQ - Bd. Leopold III - B-1110 Brussels - Belgium Fax: +32 2 707 4232 You can find further information and the latest news about the SPS Programme on our website (www.nato.int/science) You can also follow the SPS Programme on Twitter @NATO_SPS. Email: [email protected] 1605-15 NATO Graphics & Printing 1605-15 NATO NATO Emerging Security Challenges Division Security-related Scientific Cooperation with Ukraine Ukraine has been actively engaged within the frame- work of the NATO Science for Peace and Security (SPS) Programme since 1991. This collaboration was intensified following an exchange of letters on cooperation in the area of science and the environ- ment in 1999. Since May 2000, the NATO-Ukraine Joint Working Group on Scientific and Environmen- tal Cooperation is meeting on a regular basis to re- view achievements and discuss topics of interests and priority areas for future scientific cooperation. Its most recent meeting was held on 18 September 2015 at the NATO Headquarters in Brussels. In the light of the crisis in Ukraine and following the NATO Assistant Secretary General for Emerging political guidance received from Allies at the Meeting Security Challenges, Ambassador Sorin Ducaru, and of Foreign Ministers in April 2014 and at the NATO the Ambassador of Ukraine to NATO, Ihor Dolhov Wales Summit in September 2014, the SPS Pro- speak about practical cooperation at a joint interview gramme substantially stepped up its practical coop- in December 2014.