Yearbook of Polish Foreign Policy 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Power About Aspen

No. 04 ASPEN.REVIEW 2017 CENTRAL EUROPE COVER STORIES Małgorzata Fidelis, Konrad Niklewicz, Dita Přikrylová, Matthew Qvortrup, Iveta Radičová POLITICS Andrii Portnov ECONOMY Ivan Mikloš CULTURE Michał Lubina INTERVIEW Agnieszka Holland, Teddy Cruz 9 771805 679005 No. 04/2017 Women — in Power Women in Power Women Quo— Vadis, Central and Eastern Europe? — Thinking Architecture without Buildings About Aspen Aspen Review Central Europe quarterly presents current issues to the general public in the Aspenian way by adopting unusual approaches and unique viewpoints, by publishing analyses, interviews and commentaries by world-renowned professionals as well as Central European journalists and scholars. The Aspen Review is published by the Aspen Institute Central Europe. Aspen Institute Central Europe is a partner of the global Aspen network and serves as an independent platform where political, business, and non-prof-it leaders, as well as personalities from art, media, sports and science, can interact. The Institute facilitates interdisciplinary, regional cooperation, and supports young leaders in their development. The core of the Institute’s activities focuses on leadership seminars, expert meetings, and public conferences, all of which are held in a neutral manner to encourage open debate. The Institute’s Programs are divided into three areas: — Leadership Program offers educational and networking projects for outstanding young Central European professionals. Aspen Young Leaders Program brings together emerging and experienced leaders for four days of workshops, debates, and networking activities. — Policy Program enables expert discussions that support strategic thinking and interdisciplinary approach in topics as digital agenda, cities’ development and creative placemaking, art & business, education, as well as transatlantic and Visegrad cooperation. -

The Long Shadow of a Nuclear Monster Analysis

Analysis The Long Shadow of a Nuclear Monster Lithuanian responses to the Astravyets NPP in Belarus | Tomas Janeliūnas | March 2021 Title: The Long Shadow of a Nuclear Monster: Lithuanian responses to the Astravyets NPP in Belarus Author: Janeliūnas, Tomas Publication date: March 2021 Category: Analysis Cover page photo: Evaporation process seen from the cooling towers of the Russian-built Belarus nuclear power plant in Astravyets. Footage is made from the Lithuanian territory about 30 km from the nuclear plant (photo credit: Karolis Kavolelis/KKF/Scanpix Baltics). Keywords: energy policy, energy security, foreign policy, geopolitics, nuclear energy, Baltic states, Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Russia, European Union Disclaimer: The views and opinions contained in this paper are solely those of its author and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the International Centre for Defence and Security or any other organisation. ISSN 2228-2076 © International Centre for Defence and Security 63/4 Narva Rd., 10120 Tallinn, Estonia [email protected], www.icds.ee I The Long Shadow of a Nuclear Monster I About the author Tomas Janeliūnas Dr. Tomas Janeliūnas is a full-time professor at the Institute of International Relations and Political Science (IIRPS), Vilnius University, since 2015. He has been lecturing at the IIRPS since 2003 on subjects including Strategic Studies, National Security, and Foreign Policy of Lithuania, as well as Foreign Policy of the Great Powers. From 2013 to 2018 he served as the head of the Department of International Relations at the IIRPS. From 2009 to 2020 he was the Editor-in-Chief of the main Lithuanian academic quarterly of political science, Politologija. -

Annual Report the PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY of the MEDITERRANEAN

PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY OF THE MEDITERRANEAN ASSEMBLEE PARLEMENTAIRE DE LA MEDITERRANEE اﻟﺠﻤﻌﻴﺔ اﻟﺒﺮﻟﻤﺎﻧﻴﺔ ﻟﻠﺒﺤﺮ اﻷﺑﻴﺾ اﻟﻤﺘﻮﺳﻂ a v n a C © 2020 Annual Report THE PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY OF THE MEDITERRANEAN The Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean (PAM) is an international organization, which brings together 34 member parliaments from the Euro-Mediterranean and Gulf regions to discuss the most pressing common challenges, such as regional conflicts, security and counterterrorism, humanitarian crises, economic integration, climate change, mass migrations, education, human rights and inter-faith dialogue. Through this unique political forum, PAM Parliaments are able to engage in productive discussions, share legislative experience, and work together towards constructive solutions. a v n 2 a C © CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 14TH PLENARY SESSION 6 REPORT OF ACTIVITIES 9 1ST STANDING COMMITTEE - POLITICAL AND SECURITY-RELATED COOPERATION 11 2ND STANDING COMMITTEE - ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL COOPERATION 16 3RD STANDING COMMITTEE - DIALOGUE AMONG CIVILIZATIONS AND HUMAN RIGHTS 21 KEY EVENTS 2020 28 PAM 2020 DOCUMENTS – QUICK ACCESS LINKS 30 PAM AWARDS 2020 33 MANAGEMENT AND FINANCIAL REMARKS 36 FINANCIAL REPORT 39 CALENDAR 2020 49 PRELIMINARY CALENDAR 2021 60 3 a v n a C © FOREWORD Hon. Karim Darwish President of PAM Dear Colleagues and friends, It has been a privilege and an honor to act as the President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean in 2020. As this year draws to a close, I would like to reiterate my deep gratitude to all PAM delegates and their National Parliaments, the PAM Secretariat and our partner organizations for their great work and unwavering support during a time when our region Honorable Karim Darwish, President of PAM and the world face a complex array of challenges. -

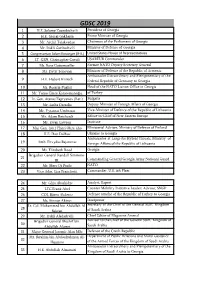

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

John III Sobieski at Vienna

John III Sobieski at Vienna John III Sobieski at Vienna Lesson plan (Polish) Lesson plan (English) Bibliografia: [w:] Jan III Sobieski, List do królowej Marii Kazimiery, oprac. Leszek Kukulski, red. , wybór , Warszawa 1962. John III Sobieski at Vienna John III Sobieski’s entry to Vienna Source: Wjazd Jana III Sobieskiego do Wiednia, domena publiczna. Link to the lesson You will learn where from and why did Ottoman Turks come to Europe; what is the history of Polish and Turkish relations in the 17th century; who was John III Sobieski and what are his merits for Poland; what is the history of the victory of Polish army – battle of Vienna of 1683. Nagranie dostępne na portalu epodreczniki.pl Since the 14th century the Ottoman Empire (the name comes from Osman – tribe leader from the medieval times) had been creating with conquests a great empire encompassing wide territories of Asia Minor, Middle East, North Africa and Europe. In Europe almost the whole Balkan Peninsula was under the sultan (Turkish ruler). The Turks threatened Poland and the Habsburg monarchy (Austria). Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldova (duchies which are parts of present‐day Romania and Moldova) were a bone of contention. In 1683 Vienna, the capital of Austria, was besieged by the Turkish army. Polish king John III Sobieski concluded an alliance with the emperor Leopold I. United Polish and German armies under the command of the Polish monarch came to the relief of Austrian capital. On 12th September 1683 there was a great battle of Vienna where John III magnificently defeated Turks. Polish mercenaries (Hussars) and artillery had the key role there. -

Print Notify

National Security Bureau https://en.bbn.gov.pl/en/news/462,President-appoints-new-Polish-government.html 2021-09-28, 07:01 16.11.2015 President appoints new Polish government President Andrzej Duda appointed the new Polish government during a Monday ceremony following a sweeping victory of the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) in the October 25 general elections. The president appointed Beata Szydlo as the new prime minister. Following is the line-up of the Beata Szydlo cabinet: Mateusz Morawiecki - deputy PM and development minister Piotr Glinski - deputy PM and culture minister Jaroslaw Gowin - deputy PM and science and higher education minister Mariusz Blaszczak - interior and administration minister fot. E. Radzikowska-Białobrzewska, Antoni Macierewicz - defence minister KPRP Witold Waszczykowski - foreign affairs minister Pawel Szalamacha - finance minister Zbigniew Ziobro - justice minister Dawid Jackiewicz - treasury minister Anna Zalewska - education minister Jan Szyszko - environment minister Elzbieta Rafalska - labour minister Krzysztof Jurgiel - agriculture minister Andrzej Adamczyk - infrastructure and construction minister Konstanty Radziwill - health minister Marek Grobarczyk - maritime economy and inland waterways minister Anna Strezynska - digitisation minister Witold Banka - sports minister Beata Kempa - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, head of PM's Office Elzbieta Witek - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, government spokesperson Henryk Kowalczyk - member of the Council of Ministers, chairman of the Government Standing Committee Mariusz Kaminski - minister, member of the Council of Ministers, coordinator of special services Krzysztof Tchorzewski - member of the Council of Ministers (expected future energy minister) "I feel fully co-responsible for the country's affairs with the prime minister and her government", President Andrzej Duda said Monday at the appointment of Poland's Beata Szydlo government. -

The Piast Horseman)

Coins issued in 2006 Coins issued in 2006 National Bank of Poland Below the eagle, on the right, an inscription: 10 Z¸, on the left, images of two spearheads on poles. Under the Eagle’s left leg, m the mint’s mark –– w . CoinsCoins Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the shadow of an armoured mounted sergeant holding a spear. On the top right, a diagonal inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI face value 200 z∏ (the Piast Horseman). The Piast Horseman metal 900/1000Au finish proof – History of the Polish Cavalry – diameter 27.00 mm weight 15.50 g mintage 10,000 pcs Obverse: On the left, an image of the Eagle established as the state Emblem of the Republic of Poland. On the right, an image of Szczerbiec (lit. notched sword), the sword that was traditionally used in the coronation ceremony of Polish kings. In the background, a motive from the sword’s hilt. On the right, face value 2 z∏ the notation of the year of issue: 2006. On the top right, a semicircular inscription: RZECZPOSPOLITA POLSKA (the metal CuAl5Zn5Sn1 alloy Republic of Poland). At the bottom, an inscription: 200 Z¸. finish standard m Under the Eagle’s left leg, the mint’s mark:––w . diameter 27.00 mm Reverse: In the centre, a stylised image of an armoured weight 8.15 g mounted sergeant with a bared sword. In the background, the mintage 1,000,000 pcs sergeant’s shadow. On the left, a semicircular inscription: JEèDZIEC PIASTOWSKI (the Piast Horseman). -

The Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Erkut, Gulden; Baypinar, Mete Basar Conference Paper Regional Integration in the Black Sea Region: the Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Erkut, Gulden; Baypinar, Mete Basar (2006) : Regional Integration in the Black Sea Region: the Case of Two Sisters, Istanbul and Odessa, 46th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Enlargement, Southern Europe and the Mediterranean", August 30th - September 3rd, 2006, Volos, Greece, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/118385 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Results of the 133Rd Assembly and Related

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) Meetings and other activities 133rd Assembly 1. Opening of the Assembly .................................................................................................... 4 2. Participation ......................................................................................................................... 4 3. Choice of an emergency item .............................................................................................. 5 4. Debates and decisions of the Assembly and its Standing Committees .............................. 6 5. Concluding sitting ................................................................................................................ 12 197th session of the Governing Council 1. Membership and Permanent Observers of the IPU ............................................................ 12 2. Financial situation of the IPU ............................................................................................... 13 3. Programme and budget for 2016 ........................................................................................ 13 4. Cooperation with the United Nations system ...................................................................... 13 5. Implementation of the IPU Strategy for 2012-2017 ............................................................. 14 6. Recent specialized meetings ............................................................................................... 15 7. Reports of plenary bodies and specialized committees ..................................................... -

100Th Anniversary of the National Flag of Poland 100Th Anniversary of the National Flag of Poland

100th Anniversary of the National Flag of Poland 100th Anniversary of the National Flag of Poland The Polish white-and-red flag is only 100 tional colours was first used on a wider Face value: 10 zł Designer: Anna Wątróbska-Wdowiarska years old, even though it is the simplest scale in 1792, during the celebrations sign symbolising the White Eagle, which of the first anniversary of the passing of Metal: Ag 925/1000 Issuer: NBP has been the emblem of Poland for eight the Constitution of 3rd May. In 1831, the Finish: proof, UV print centuries. The upper white stripe of the Sejm of the Congress Kingdom of Poland Diameter: 32.00 mm The coins, commissioned by NBP, flag symbolises the Eagle, while the red adopted a white-and-red cockade as the Weight: 14.14 g were struck by Mennica Polska S.A. one symbolises the colour of the es- official national symbol. The design of the Edge: plain cutcheon. The flag in the form in which it flag used these days was only introduced Mintage: up to 13,000 pcs All Polish collector coins feature: is used these days was introduced only by the Legislative Sejm of the reborn Re- face value; image of the Eagle established after Poland regained its independence public of Poland on 1 August 1919. In the as the state emblem of the Republic of following the partitions. In the Middle first act on the coat-of-arms and the na- Poland; inscription: Rzeczpospolita Polska Ages, the ensign carried by knights of the tional colours of the Republic of Poland, year of issue. -

Security Intransition

SECURITY INTRANSITION HOW to COUNTER AGGRESSION WITH LIMITED Resources Kyiv 2016 This report was prepared within the “Think Tank Support Initiative” implemented by the International Renaissance Foundation (IRF) in partnership with Think Tank Fund (TTF) with financial support of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine. The contents are those of the Institute of World Policy and do not necessarily re- flect the views of the Swedish Government, the International Renaissance Founda- tion, Think Tank Fund. No part of this research may be reproduced or transferred in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or including photocopying or by any information storage retrieval system, without the proper reference to the original source. Authors: Sergiy Solodkyy, Oleksiy Semeniy, Leonid Litra, Olena Betliy, Mykola Bielieskov, Olga Lymar, Yana Sayenko, Yaroslav Lytvynenko, Zachary A. Reeves Cover Picture: Michelangelo, David and Goliath, 1509 © Institute of World Policy, 2016 CONTENTS Foreword 5 1. Asymmetric security model 7 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 1.1. Definition of asymmetric security model ……………………………………………… 10 1.2. Key elements in development of asymmetric security model ………………… 12 1.3. The model’s stability (sustainability) in the short, medium and long term 21 Recommendations ………………………………………………………………………………………… 23 Advantages and disadvantages of the model …………………………………………………… 24 2. A security model based on a bilateral US-UA pact 25 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 25 2.2. Best-case security cooperation -

Armed Resistance in the Ghettos and Camps

ARMED RESISTANCE IN THE GHETTOS AND CAMPS RESISTANCE IN THE GHETTOS On January 18, 1943, German forces entered the Warsaw the Germans withdrew from the ghetto. The remaining ghetto in order to arrest Jews and deport them. To inhabitants believed that the armed resistance combined their astonishment, young Jews offered them armed with the difficulties in finding Jews in hiding, had resistance and actually drove the German forces out of led to the end of the Aktion. As a result, over the next the ghetto before they were able to finish their ruthless months the armed undergrounds sought to strengthen task. This armed resistance came on the heels of the themselves and the vast majority of ghetto residents and great deportation that had occurred in the summer zealously built more and better bunkers in which to hide. and early autumn of 1942, which had resulted in the dispatch of 300,000 Jews, the vast majority of the ghetto’s inhabitants to Nazi camps, almost all to the Treblinka extermination camp. About 60,000 Jews remained in the ghetto, traumatized by the deportations and believing that the Germans had not deported them and would not deport them since they wanted their labor. Two undergrounds led by youth activists, with several hundred members, coalesced between the end of the first wave of deportations and the events of January. During four days in January, the Germans sought to round up Jews and the armed resistance continued. The ghetto inhabitants went through a swift change, Left: Waffen SS soldiers locating Jews in dugouts. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, 6003996 no longer believing that their value as labor would Right: HeHalutz women captured with weapons during the safeguard them.