SCIENTIFIC YEARBOOK Issue Twelve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCSEJ WEEKLY TOP 10 Washington, DC June 29

NCSEJ WEEKLY TOP 10 Washington, D.C. June 29, 2018 Poland’s Holocaust Law Weakened After ‘Storm and Consternation’ By Marc Santora New York Times, June 27, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/27/world/europe/poland-holocaust-law.html WARSAW — Just a few months after making it illegal to accuse the Polish nation of complicity in the Holocaust, Poland backpedaled on Wednesday, moving to defang the controversial law by eliminating criminal penalties for violators. The United States and other traditional allies had excoriated the Polish government over the law, passed in February, condemning it as largely unenforceable, a threat to free speech, and an act of historical revisionism. Although both ethnic Poles and Jews living in Poland suffered unfathomable loss during World War II, the law drove a wedge between Israel and Poland, setting back years of hard work to repair bitter feelings. Both houses of Parliament voted on Wednesday to remove the criminal penalties, after an emotional session that saw one nationalist lawmaker try to block access to the podium. President Andrzej Duda later signed the measure into law, his office said. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel welcomed the move, saying in a statement that he was pleased Poland rescinded provisions that “caused a storm and consternation in Israel and among the international community.” By amending the statute, Poland’s governing Law and Justice party hoped to repair some of the diplomatic damage it had caused, even as it pressed ahead with sweeping judicial overhauls that have been condemned by European Union leaders as a threat to the rule of law. -

Yes 2012 Report.Pdf

CONFERENCE OPENING Dear Friends, Today, countries are in a global race that gets faster and faster. I am not a political scientist - as an art collector I like to use art when I speak about global challenges. Let me use the famous photographer Andreas Gursky’s “Boxenstopp” as an analogy. A pit stop in Formula 1. One team is blue and yellow. This is Ukraine; these are Ukraine’s colours. What is the Ukrainian team doing? I believe - reforms. In the global race, reforms are pit stops allowing you to change and speed up. Some countries which were slow before improve their position. Like cars that put on the right new tires and fill up with the right amount of gasoline, they can overtake others. Others put on the wrong equip- ment or lose too much time in the pit stop and fall behind. I hope Ukraine’s team will be successful. And I hope for all of us this conference will be an intellectual pit stop where we refuel and re-equip ourselves, take in new energy and ideas, to help all our respective countries become smarter, better, more productive, more just. For this, we have fantastic speakers with us in Yalta, political leaders, business leaders, social leaders, intellectuals. I look forward to our discussions. Victor Pinchuk, Founder and Member of the Board, Yalta European Strategy 1 AGENDA 9th YALTA ANNUAL MEETING Ukraine and the World: Addressing Tomorrow’s Challenges Together AGENDA Thursday, September 13 21:20 – 21:25 Welcoming Remarks Aleksander Kwasniewski, President of Poland (1995-2005); Chairman of the Board, Yalta European Strategy -

17Th Plenary Session

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities 20 th SESSION CG(20)7 2 March 2011 Local elections in Ukraine (31 October 2010) Bureau of the Congress Rapporteur: Nigel MERMAGEN, United Kingdom (L, ILDG)1 A. Draft resolution....................................................................................................................................2 B. Draft recommendation.........................................................................................................................2 C. Explanatory memorandum..................................................................................................................4 Summary Following the official invitation from the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine to observe the local elections on 31 October 2010, the Congress appointed an observer delegation, headed by Gudrun Mosler-Törnström (R, Austria, SOC), Member and Vice-President of the State Parliament of Salzburg. Councillor Nigel Mermagen (L, UK, ILDG) was appointed Rapporteur. The delegation was composed of fifteen members of the Congress and four members of the EU Committee of the Regions, assisted by four members of the Congress secretariat. The delegation concluded, after pre-election and actual election observation missions, that local elections in Ukraine were generally conducted in a calm and orderly manner. It also noted with satisfaction that for the first time, local elections were held separately from parliamentary ones, as requested in the past by the Congress. No indications of systematic fraud were brought -

Central Asia the Caucasus

CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition VolumeISSN 1404-609121 Issue 4 ( Print2020) ISSN 2002-3839 (Online) CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition Journal of Social and Political Studies Volume 21 Issue 4 2020 CA&C Press AB SWEDEN 1 Volume 21 Issue 4 2020 CENTRAL ASIA AND THE CAUCASUS English Edition FOUNDED AND PUBLISHED BY INSTITUTE FOR CENTRAL ASIAN AND CAUCASIAN STUDIES Registration number: 620720-0459 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden CA&C PRESS AB Publishing House Registration number: 556699-5964 Companies registration Office of Sweden Journal registration number: 23 614 State Administration for Patents and Registration of Sweden E d i t o r s Murad ESENOV Editor-in-Chief Tel./fax: (46) 70 232 16 55; E-mail: [email protected] Kalamkas represents the journal in Kazakhstan (Nur-Sultan) YESSIMOVA Tel./fax: (7 - 701) 7408600; E-mail: [email protected] Ainura represents the journal in Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek) ELEBAEVA Tel./fax: (996 - 312) 61 30 36; E-mail: [email protected] Saodat OLIMOVA represents the journal in Tajikistan (Dushanbe) Tel.: (992 372) 21 89 95; E-mail: [email protected] Farkhad represents the journal in Uzbekistan (Tashkent) TOLIPOV Tel.: (9987 - 1) 225 43 22; E-mail: [email protected] Kenan represents the journal in Azerbaijan (Baku) ALLAHVERDIEV Tel.: (+994 - 50) 325 10 50; E-mail: [email protected] David represents the journal in Armenia (Erevan) PETROSYAN Tel.: (374 - 10) 56 88 10; E-mail: [email protected] Vakhtang represents the journal in Georgia (Tbilisi) -

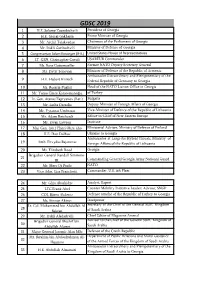

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

3. Farm Restructuring Outcomes: Evidence from the Field

WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPER NO. 459 Europeand Central Asi Environmentallyand Socially Sustainable S DevelopmentSeries Work In progreT 4 for public disculion WTP=459 Public Disclosure Authorized Ukraine Reviewof Farm RestructuringExperiences Public Disclosure Authorized 1~~~~~~~~~~~ L< S.IU.z -. Public Disclosure Authorized Zvi Lerman Public Disclosure Authorized Csaba Csaki Recent World Bank Technical Papers No. 379 Shah and Nagpal, eds., Urban Air Quality Management Strategy in Asia: Jakarta Report No. 380 Shah and Nagpal, eds., Urban Air Quality Management Strategy in Asia: Metro Manila Report No. 381 Shah and Nagpal, eds., Urban Air Quality Management Strategy in Asia: Greater Mumbai Report No. 382 Barker, Tenenbaum, and Woolf, Governance and Regulation of Power Pools and System Operators: An International Comparison No. 383 Goldman, Ergas, Ralph, and Felker, Technology Institutions and Policies: Their Role in Developing TechnologicalCapability in Industry No. 384 Kojima and Okada, Catching Up to Leadership: The Role of Technology Support Institutions in Japan's Casting Sector No. 385 Rowat, Lubrano, and Porrata, Competition Policy and MERCOSUR No. 386 Dinar and Subramanian, Water Pricing Experiences: An International Perspective No. 387 Oskarsson, Berglund, Seling, Snellman, Stenback, and Fritz, A Planner's Guide for Selecting Clean-Coal Technologiesfor Power Plants No. 388 Sanjayan, Shen, and Jansen, Experiences with Integrated-Conservation Development Projects in Asia No. 389 International Commission on Irrigation and Drainage (ICID), Planning the Management, Operation, and Maintenance of Irrigation and Drainage Systems: A Guidefor the Preparation of Strategies and Manuals No. 390 Foster, Lawrence, and Morris, Groundwater in Urban Development: Assessing Management Needs and Formulating Policy Strategies No. 391 Lovei and Weiss, Jr., Environmental Management and Institutions in OECD Countries" Lessons from Experience No. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1993, No.23

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: • Ukraine's search for security by Dr. Roman Solchanyk — page 2. • Chornobyl victim needs bone marrow transplant ~ page 4 • Teaching English in Ukraine program is under way - page 1 1 Publishfd by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-prof it association rainianWee Vol. LXI No. 23 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JUNE 6, 1993 50 cents New York commemorates Tensions mount over Black Sea Fleet by Marta Kolomayets Sea Fleet until 1995. 60th anniversary of Famine Kyyiv Press Bureau More than half the fleet — 203 ships — has raised the ensign of St. Andrew, by Andrij Wynnyckyj inaccurate reports carried in the press," KYYIV — Ukrainian President the flag of the Russian Imperial Navy. ranging from those of New York Times Leonid Kravchuk has asked for a summit NEW YORK — On June 1, the New None of the fleet's Warships, however, reporter Walter Duranty written in the meeting with Russian leader Boris have raised the ensign. On Friday, May York area's Ukrainian Americans com 1930s, to recent Soviet denials and Yeltsin to try to resolve mounting ten memorated the 60th anniversary of the Western attempts to smear famine sions surrounding control of the Black (Continued on page 13) tragic Soviet-induced famine of І932- researchers. Sea Fleet. 1933 with a "Day of Remembrance," "Now the facts are on the table," Mr. In response, Russian Foreign Minister consisting of an afternoon symposium Oilman said. "The archives have been Andrei Kozyrev is scheduled to arrive in Parliament begins held at the Ukrainian Institute of opened in Moscow and in Kyyiv, and the Ukraine on Friday morning, June 4, to America, and an evening requiem for the Ukrainian Holocaust has been revealed arrange the meeting between the two debate on START victims held at St. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992, No.26

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

University of Alberta the European Union's Migration Co

University of Alberta The European Union's Migration Co-operation with Its Eastern Neighbours: The Art of EU Governance beyond its Borders by Lyubov Zhyznomirska A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science ©Lyubov Zhyznomirska Spring 2013 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. ABSTRACT The dissertation explores the European Union’s (EU) migration relations with Ukraine and Russia since the break-up of the Soviet Union, up until 2011. Utilizing a comparative research design and discursive analytical approach, it critically examines the external dimension of the EU’s immigration policies in order to understand how the EU’s “migration diplomacy” affects the cooperating countries’ politics and policies on migration. The research evaluates the EU’s impact by analyzing the EU-Ukraine and EU-Russia co-operation on irregular migration and the mobility of their citizens through the prism of the domestic discourses and policies on international migration. -

Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Jewish Cemetries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine Samuel D. Gruber United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Gruber, Samuel D., "Jewish Cemeteries, Synagogues, and Mass Grave Sites in Ukraine" (2005). Full list of publications from School of Architecture. Paper 94. http://surface.syr.edu/arc/94 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JEWISH CEMETERIES, SYNAGOGUES, AND MASS GRAVE SITES IN UKRAINE United States Commission for the Preservation of America’s Heritage Abroad 2005 UNITED STATES COMMISSION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICA’S HERITAGE ABROAD Warren L. Miller, Chairman McLean, VA Members: Ned Bandler August B. Pust Bridgewater, CT Euclid, OH Chaskel Besser Menno Ratzker New York, NY Monsey, NY Amy S. Epstein Harriet Rotter Pinellas Park, FL Bingham Farms, MI Edgar Gluck Lee Seeman Brooklyn, NY Great Neck, NY Phyllis Kaminsky Steven E. Some Potomac, MD Princeton, NJ Zvi Kestenbaum Irving Stolberg Brooklyn, NY New Haven, CT Daniel Lapin Ari Storch Mercer Island, WA Potomac, MD Gary J. Lavine Staff: Fayetteville, NY Jeffrey L. Farrow Michael B. Levy Executive Director Washington, DC Samuel Gruber Rachmiel -

Enhancing Co-Operation to Prevent Trafficking in Human Beings in the Mediterranean Region Isbn: 978-92-9234-442-9

Offi ce of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Traffi cking in Human Beings ENHANCING CO-OPERATION TO PREVENT TRAFFICKING IN HUMAN BEINGS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION ISBN: 978-92-9234-442-9 Published by the OSCE Offi ce of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Traffi cking in Human Beings Wallnerstr. 6, 1010 Vienna, Austria Tel: + 43 1 51436 6664 Fax: + 43 1 51436 6299 email: [email protected] © 2013 OSCE/Offi ce of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Traffi cking in Human Beings Copyright: “All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/Offi ce of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Traffi cking in Human Beings as the source.” Design: Tina Feiertag, Vienna Illustration on cover: Mediterraneo (2007), Acrylic on raw canvas 40x50cm, by Adriano Parracciani Illustrations on page 11, 19, 35, 41, 49: Tempera on brick 10x10 cm by Adriano Parracciani Photos on page 8, 10, 14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27, 33: Enrico Para/Camera dei Deputati Photo on page 8, 43: Alfred Kueppers Photos on page 4: OSCE/Mikhail Evstafi ev Photos on page 32: OSCE/Alberto Andreani Cite as: OSCE Offi ce of the Special Representative and Co-ordinator for Combating Traffi cking in Human Beings, Enhancing Co-operation to Prevent Traffi cking in Human Beings in the Mediterranean Region (November 2013). The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is a pan-European security body whose 57 participating States span the geographical area from Vancouver to Vladivostok. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages