Ladnere66921.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mª Fernanda Santiago Bolaños CURRICULUM VITAE

Mª Fernanda Santiago Bolaños CURRICULUM VITAE 1 CURRICULUM VITAE: MARIFÉ SANTIAGO BOLAÑOS ÍNDICE: Datos personales……………………………………………………………………………………..………. Datos profesionales y académicos…………………………………………………..…………….... Titulación……………………………………………………………………………………..…….. Datos profesionales………………………………………………………………………..…… Tesis doctorales dirigidas (ya defendidas)……………………………………..…….. Tesis doctorales vivas…………………………………………………………………………. Tribunales Tesis doctorales………………………………………………………………… Otros méritos profesionales y académicos……………………………………..……. Condecoraciones………………………………………………………………………………..… Otros datos de interés profesional y académico…………………………..………. Publicaciones………………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 1.- Libros y artículos recogidos en libros…………………......………………….…… 2.- Artículos recogidos en revistas y catálogos………………………………..….. 3.- Otras publicaciones……………………………………………………………….………. Ámbito literario (incluyendo antologías)………………………………………….….. A) Libros de Poesía…………………………………………………………………………….. B) Poemas en otras publicaciones (individuales y colectivas)…………….. C) Relatos…………………………………………………………………………………………… D) Novelas……………………………………………………………………………………..…… E) Teatro…………………………………………………………………………………….………. Conferencias, cursos, ponencias y seminarios impartidos………………………………..… Asistencia a cursos, seminarios, congresos……………………………………………………...… Actos en los que ha participado (desde verano de 2013)………………………………..…. Otras actividades………………………………………………………………………………………..……… 2 CURRICULUM VITAE DATOS PERSONALES: -NOMBRE Y APELLIDOS: Mª Fernanda Santiago Bolaños -

Exit Exam for Spanish Majors

“TUTORIAL FOR GRADUATING MAJORS” SPANISH 3500 This course prepares majors for the completion of their requirements in the B.A. in Spanish through advising by a designated professor. The course concludes with the Written Exit Exam, a 2-hour long comprehensive exam written in Spanish. 1 credit. Pass/Fail. The exam is made up of 3 parts: 1) Literature (40 minutes);2) Culture/Civilization (40 minutes); 3) Advanced Grammar/Phonetics (40 minutes). In literature and in civilization, the candidate receives 10 topics, to choose 6 of them, and to write a paragraph for each. In Advanced Grammar/Phonetics some choices also occur, according to specific instructions. Approximately one month prior to the Written Exit Exam (scheduled during final exams week), an oral mid-term exam occurs. Both the mid-term and the final exams are based on “The Topics Lists” (see attached), and the guidance given by the “designated professor”. A jury made up of three professors examines the candidate in both cases. If the candidate fails one of the 3 parts of the written exam, that part may be retaken within 7- 10 days of the initial exam IN the same semester. PART ONE: LITERATURA I. Literatura medieval / Siglo de Oro 1) ALFONSO X, EL SABIO 2) LAS JARCHAS MOZÁRABES 3) EL JUGLAR 4) EL POEMA DE MIO CID 5) EL TROVADOR 6) GONZALO DE BERCEO 7) EL MESTER DE CLERESÍA 8) DON JUAN MANUEL 9) LOS ROMANCES 10) EL VILLANCICO 11) EL SONETO 12) EL LAZARILLO DE TORMES 13) EL ESTILO BARROCO 14) LOPE DE VEGA 15) CERVANTES 16) PEDRO CALDERÓN DE LA BARCA II. -

Course FB-26 the CIVIL WAR and PRESENT–DAY SPANISH LITERATURE Lecturer: D

Course FB-26 THE CIVIL WAR AND PRESENT–DAY SPANISH LITERATURE Lecturer: D. Cipriano Lopez Lorenzo [email protected] Back-up Lecturer: D. Ivan Garcia [email protected] OBJECTIVES The aim of this Course is to explore the interaction of History and Literature, using as a point of departure an historical event which has had wide-ranging effects upon Spanish literary output: the Civil War of 1936. An overview of the cultural and literary context of the nineteen thirties will be provided, as well as of the evolution of the Civil War and its consequences for Spanish Literature between the nineteen forties and the present day. In this way, what will be sought after is a clearer understanding of the contemporary literary scenario via its development during the second half of the twentieth century. Methodology A theoretical-practical approach will be adopted in class sessions: the input-lecture on each syllabus point will be enhanced by the discussion of the readings which have been selected. Syllabus 1. The socio-political context: from Republic to Dictatorship. The antecedents of the Civil War. 2. The Spanish Civil War: literature within Spain and the literature of exile. 3. The Civil War and the contemporary Spanish novel: from the post-war period to the present day. - Narrative written from within exile: La cabeza del cordero by Francisco Ayala. - The Novel in Spain: Los santos inocentes by Miguel Delibes and La voz dormida by Dulce Chacon. 4. The Civil War and Drama: from the post-war period to the present time. - The drama of protest and grievance: Historia de una escalera by Antonio Buero Vallejo. -

Sample: SPAN 5960 Spanish M.A. Comprehensive Examination

Sample: SPAN 5960 Spanish M.A. Comprehensive Examination The Spanish M.A. Comprehensive is given three Fridays or three Saturdays in a row during the spring semester. Each examination has a total of five questions, which may be subdivided into groups. Candidates answer 3 questions out of 5 in each exam. Forty-five minutes are allotted for each question. Exam sections are as follows: First Day: Spanish Literature: Beginning to 1700 1. Explique y comente la evolución de la poesía castellana desde las jarchas y el Cantar de Mío Cid hasta la lírica de Garcilaso. 2. Comente el Lazarillo de Tormes como prototipo de la novela de protesta social. 3. Comente los cambios de nombre en Don Quijote y su importancia temática. 4. ¿Cuáles son los elementos de una obra teatral que justifiquen su clasificación como tragedia? Aplique sus comentarios de una manera específica a una obra de Calderón de la Barca o de Lope de Vega. 5. Se ha dicho que el lema del Neoclasicismo/Ilustración podría ser: "Todo para el pueblo, pero sin el pueblo." Explique esto en relación con la obra de Moratín. Spanish Literature: 1700 to Present 1. Contraste el lirismo romántico en Espronceda y Bécquer tomando en consideración los temas que tratan y su visión del mundo. 2. Comente la tendencia social en las obras de Valera, Galdós o Blasco Ibáñez. 3. Caracterice a la Generación del 98, y aplique sus conceptos a tres de los siguientes autores: Unamuno, Baroja, Valle-Inclán, Benavente, Machado. 4. Comente la tendencia introspectiva en las obras de dos de los siguientes poetas: Jiménez, Salinas, Guillén. -

Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama

Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama By Andreea Iulia Sprinceana A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair Professor Michael Iarocci Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2014 Copyright Andreea Iulia Sprinceana, 2014 All rights reserved. Abstract Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama by Andreea Iulia Sprinceana Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair This dissertation explores the manifestations, uses and appropriations of history in key Spanish plays from the 1950s to the present. The relationship between the stage and history casts new light on Spain’s most critical phases in recent history. The authors studied were and are conscious of making history under the dictatorship, during the Transition and at the dawn of the 21st century. As instruments of civic action, their plays perform that awareness and invite spectators to recognize themselves as players in the process. The dissertation opens with a comparative analysis of plays written by Antonio Buero Vallejo and Alfonso Sastre between the 1950s and the Transition (1977). While scholars have tended to contrast these two playwrights focusing on their responses to censorship, I propose that Buero and Sastre gravitated towards a poetics of forgiveness through the model of the failed tragic hero. The following chapter explores plays written by José Sanchis Sinisterra during the Transition and the outset of the new democracy (1977-1994), that problematize the tension between the new political order and the old, imperial rhetoric of the Franco regime. -

Lecturer: the SPANISH CIVIL WAR and PRESENT–DAY

Course FB-26 THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR AND PRESENT–DAY SPANISH LITERATURE (45 class hours) Lecturer: Ana Davis González ([email protected]) Co- Lecturer: Emilio Ocampos Palomar ([email protected]) OBJECTIVES The aim of this Course is to explore the interaction of History and Literature, using as a point of departure an historical event which has had wide-ranging effects upon Spanish literary output: the Civil War of 1936. An overview of the cultural and literary context of the nineteen thirties will be provided, as well as of the evolution of the Civil War and its consequences for Spanish Literature between the nineteen forties and the present day. In this way, what will be sought after is a clearer understanding of the contemporary literary scene via its development during the second half of the twentieth century. METHODOLOGY An interactive theoretical-practical approach will be adopted in class sessions: the explicative input-lecture on each syllabus item will be enhanced by the discussion of the readings which have been selected. SYLLABUS 1. The Socio-Political Context: from Republic to Dictatorship. The Antecedents of the Civil War. Spain’s Literary Scene prior to the Outbreak of the War. 2. Spanish Literature during the Civil War. 3. Two Spains, Two Literatures? The Cultural Panorama and the Consequences of the War on Spain’s Literary Output: Official Literature and the Literature of Homeland Exile. 4. The Evolution of Spanish Narrative from the Post-War Period to the Present Day: Kinds of Realism and Kinds of Experimentation. 5. Drama after the Civil War: from the Crisis in Theater to Independent Theater. -

Pdf Historia Política E Historia Social En El Teatro De Antonio Buero Vallejo

HISTORIA POLÍTICA E HISTORIA SOCIAL EN EL TEATRO DE ANTONIO BUERO VALLEJO, ILUSTRADAS CON “HISTORIA DE UNA ESCALERA” Prólogo La meta perseguida con este texto-conferencia es la de mostrar, primero, las fases histórico-políticas relevan tes de un país (España->Madrid) y época (1936-1975) precisos, pero no consultando exacta y únicamente los li bros y manuales de dicha materia, sino constatando cómo ésta toma forma (implícita o explícitamente) en las obras literarias. Lo que quiere decir, segundo, que los hechos histórico-políticos van a formar ‘el hilo conductor’ de nuestra actividad; actividad que, entonces, pretende cal car la época e importancia que esos hechos han desperta do en algunas obras literarias de los que éstas surgen y son al mismo tiempo también espejo reflector. No olvidemos las palabras que escribió Stendhal (1783- 1842) en su gran novela Le Rouge et le Noir. Un roman: c’est un miroir qu'on promène le long d’un chemin. SAINT-REAL.1 1 “Una novela: es un espejo que paseamos a lo largo de un camino”. SAINT-REAL (Traducción Nuestra). Stendhal. Le Rouge et le Noir. Paris : Garnier-Flammarion, 1964, p. 100. 407 ÁNGEL DÍAZ ARENAS BBMR LXXVI, 2000 Palabras a las que no sólo podemos, sino inclusive debemos añadir otras no menos sabias y certeras escritas por Nicolás Boileau (1636-1711) en el verso 295 de “El Arte Poético”: Instruiré et plaire.2 Aserto que explicita claramente nuestra intención, aun que invirtiéndolo, ‘deleitar e instruir’; ya que su audición y lectura debe ser ligera, apacible y ‘deleitosa’, pero al mismo tiempo ‘instructiva’, informativa y esclarecedora. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6q8939qt Author Sprinceana, Andreea Iulia Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama By Andreea Iulia Sprinceana A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair Professor Michael Iarocci Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2014 Copyright Andreea Iulia Sprinceana, 2014 All rights reserved. Abstract Staging History in Modern and Contemporary Spanish Drama by Andreea Iulia Sprinceana Doctor of Philosophy in Romance Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Dru Dougherty, Chair This dissertation explores the manifestations, uses and appropriations of history in key Spanish plays from the 1950s to the present. The relationship between the stage and history casts new light on Spain’s most critical phases in recent history. The authors studied were and are conscious of making history under the dictatorship, during the Transition and at the dawn of the 21st century. As instruments of civic action, their plays perform that awareness and invite spectators to recognize themselves as players in the process. The dissertation opens with a comparative analysis of plays written by Antonio Buero Vallejo and Alfonso Sastre between the 1950s and the Transition (1977). While scholars have tended to contrast these two playwrights focusing on their responses to censorship, I propose that Buero and Sastre gravitated towards a poetics of forgiveness through the model of the failed tragic hero. -

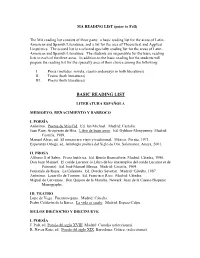

M.A. READING LIST Prior to Fall

MA READING LIST (prior to Fall) The MA reading list consists of three parts: a basic reading list for the areas of Latin- American and Spanish Literatures, and a list for the area of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. The second list is a selected specialty reading list for the areas of Latin- American and Spanish Literatures. The students are responsible for the basic reading lists in each of the three areas. In addition to the basic reading list the students will prepare the reading list for the specialty area of their choice among the following: I. Prosa (includes novela, cuento andensayo in both literatures) II. Teatro (both literatures) III. Poesía (both literatures) BASIC READING LIST LITERATURA ESPAÑOLA MEDIOEVO, RENACIMIENTO Y BARROCO I. POESÍA Anónimo. Poema de Mio Cid. Ed. Ian Michael. Madrid: Castalia. Juan Ruiz, Arcipreste de Hita. Libro de buen amor. Ed. Gybbon-Monypenny. Madrid: Castalia, 1989. Manuel Alvar, ed. El romancero viejo y tradicional. México: Porrúa, 1971. Esperanza Ortega, ed. Antologia poética del Siglo de Oro. Salamanca: Anaya, 2001. II. PROSA Alfonso X el Sabio. Prosa histórica. Ed. Benito Brancaforte. Madrid: Cátedra, 1990. Don Juan Manuel. El conde Lucanor (o Libro de los enxiemplos del conde Lucanor et de Patronio). Ed. José Manuel Blecua. Madrid: Castalia, 1969. Fernando de Rojas. La Celestina. Ed. Dorohy Severyn. Madrid: Cátedra, 1987. Anónimo. Lazarillo de Tormes. Ed. Francisco Rico. Madrid: Cátedra. Miguel de Cervantes. Don Quijote de la Mancha. Newark: Juan de la Cuesta-Hispanic Monographs. III. TEATRO Lope de Vega. Fuenteovejuna. Madrid: Cátedra. Pedro Calderón de la Barca. La vida es sueño. -

Peninsular Literature (January 2017)

University of Central Florida Department of Modern Languages and Literatures: Spanish MA Reading List for Spanish Peninsular Literature (January 2017) I. PART ONE A. Medieval Literature Anónimo. El Cantar de Mío Cid. Gonzalo de Berceo. Milagros de Nuestra Señora. Don Juan Manuel. El libro de los Ejemplos del Conde Lucanor. Juan Ruiz, arcipreste de Hita. El libro del buen amor. Jorge Manrique. Coplas por la muerte de su padre. Selecciones del Romancero o Poesía de cancionero. Fernando de Rojas. Tragicomedia de Calixto y Melibea:La Celestina. Alfonso X, el Sabio. Las siete partidas o Cantiga XCIV. El Arcipreste de Talavera. "El Corbacho." Juan de Flores. Grisel y Mirabella (novela sentimental). B. Golden Age Poesía Garcilaso de la Vega. Sonetos. Fray Luis de León. Odas. San Juan de la Cruz. Cántico espiritual o Noche oscura. Luis de Góngora. Soledades o Romance I. Francisco de Quevedo. Heráclito cristiano o Sonetos. Teatro Lope de Vega. Fuenteovejuna o El caballero de Olmedo. Calderón de la Barca. La vida es sueño. Tirso de Molina. El condenado por desconfiado o El burlador de Sevilla. Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. La verdad sospechosa. María de Zayas y Sotomayor. La traición en la amistad. Prosa Anónimo. Lazarillo de Tormes. Santa Teresa de Ávila. Libro de su vida. Miguel de Cervantes. Don Quijote de la Mancha Parte I (1605) y Parte II (1615). Miguel de Cervantes. Novelas ejemplares. María de Zayas y Sotomayor. Novelas ejemplares y amorosas. Ana Caro. Valor, agravio y mujer. Francisco de Quevedo. Vida del buscón. C. 18th Century Fray Benito Jerónimo Feijoo. Cartas eruditas y curiosas. -

El Drama De Antonio Buero Vallejo: Implicaciones De La Desviacion, La Estigmatizacion, La Normalidad Y Los Valores

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-1971 El Drama de Antonio Buero Vallejo: Implicaciones de La Desviacion, La Estigmatizacion, La Normalidad y Los Valores Mary F. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Mary F., "El Drama de Antonio Buero Vallejo: Implicaciones de La Desviacion, La Estigmatizacion, La Normalidad y Los Valores" (1971). Master's Theses. 2931. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2931 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EL DRAMA DE ANTONIO BUERO VALLEJO: IMPLICACIONES DE LA DESVIACION, LA ESTIGMATIZACION, LA NORMALIDAD Y LOS VALORES por Mary F. Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1971 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. AGRADECIMIENTOS Quisiera agradecer al Dr. Manuel Mantero por sus consejos du rante la preparacion de esta tesis. Su ayuaa ha sido imprescindible y su incentivo un apoyo constante. A la vez, quisiera agradecer a mi marido Bruce— quien ha sido paciente y comprensivo a pesar de no poder ni leer ni entender mis estudios. Mary F . Smith Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Name Surname

Mariano de Paco Serrano. Currículum Vitae. Datos personales Murcia, 1972 España +34 649386197 [email protected] Formación Académica Doctor en Literatura Española. Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada. (Sobresaliente Cum Laude por unanimidad del Tribunal). Diploma de Estudios Avanzados en Literatura Española. Licenciado en Derecho. Información complementaria Director Artístico Asociado del Teatro Círculo de Nueva York. Letrado (no ejerciente) del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Murcia. Comité de Expertos de las Artes Escénicas AECID y Consejo Estatal de las Artes Escénicas y de la Música INAEM (2010-2011). Presidente de la Coordinadora de Ferias de Artes Escénicas del Estado Español (2009-2011). Académico Fundador de la Academia de las Artes Escénicas de España. Miembro del Instituto del Teatro de Madrid (ITEM). Profesor del Máster de Gestión Cultural: MBA en Empresas e Instituciones Culturales, Universidad Complutense de Madrid (desde 2007). Profesor del Máster Universitario en Estudios Avanzados en Teatro de la Uiversidad Internacional de la Rioja. Asignaturas impartidas: Sistemas de Interpretación Actoral y Producción en la coyuntura contemporánea (desde 2017). Profesor del Máster Universitario en Gestión y Emprendimiento de Proyectos Culturales de la Universidad Internacional de la Rioja (UNIR) (desde 2019). Miembro de la Asociación de Directores de Escena de España (ADE). Experiencia Profesional en Gestión. Desde 2016 Gerente Academia de las Artes Escénicas de España. Fundación de la Academia de las Artes Escénicas de España. 2008-2011 Gerente Feria de Artes Escénicas de Madrid. MADferia. 2005-2007 Coordinador de Artes Escénicas Sociedad Estatal de Acción Cultural Exterior en los proyectos Iberoamericanos: • España en Chile. Festival Internacional de Teatro Santiago a Mil.