APULUM LI CARPATHIAN HEARTLANDS Studies on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orientalisms in Bible Lands

eoujin ajiiiBOR Rice ^^ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES GIFT OF Carl ©ton Shay [GREEN FUND BOOK No. 16] Orientalisms IN Bible Lands GIVING LIGHT FROM CUSTOMS, HABITS, MANNERS, IMAGERY, THOUGHT AND LIFE IN THE EAST FOR BIBLE STUDENTS. BY EDWIN WILBUR RICE, D. D. AUTHOR OK " " Our Sixty-Six Sacred Commentaries on the Gospels and The Acts ; " " " " of the Bible ; Handy Books ; People's Dictionary Helps for Busy Workers," etc. PHILADELPHIA: The American Sunday-School Union, 1816 Chestnut Street. Copyright, 1910,) by The American Sunday-School Union —— <v CONTENTS. • • • • • I. The Oriental Family • • • " ine The Bible—Oriental Color.—Overturned Customs.— "Father."—No Courtship.—The Son.—The Father Rules.— Patriarchal Rule.—Semites and Hebrews. Betrothal i6 II. Forming the Oriental Family: Love-making Unknown. — Girl's Gifts. — Wife-seeking. Matchmaking.—The Contract.—The Dowry.—How Set- tied.—How Paid.—Second Marriage.—Exempt from Duties. III. Marriage Processions • • • • 24 Parades in Public—Bridal Costumes.—Bnde's Proces- sion (In Hauran,—In Egypt and India).—Bridegroom's Procession.—The Midnight Call.—The Shut Door. IV. Marriage Feasts • 3^ Great Feasts.—Its Magnificence.—Its Variety.—Congratula- tions.—Unveiling the Face.—Wedding Garment.—Display of Gifts.—Capturing the Bride.—In Old Babylonia. V. The Household ; • • • 39 Training a Wife. —Primitive Order.—The Social Unit. Childless. —Divorce. VI. Oriental Children 43 Joy Over Children.—The Son-heir.-Family Names.—Why Given?—The Babe.—How Carried.—Child Growth. Steps and Grades. VII. Oriental Child's Plays and Games 49 Shy and Actors.—Kinds of Plavs.—Toys in the East.— Ball Games.—Athletic Games.—Children Happy.—Japanese Children. -

Strange Grooves in the Pennines, United Kingdom

Rock Art Research 2016 - Volume 33, Number 1, pp. 000-000. D. SHEPHERD and F. JOLLEY KEYWORDS: Groove – Gritstone – Pennine – Anthropogenic marking – Petroglyph STRANGE GROOVES IN THE PENNINES, UNITED KINGDOM David Shepherd and Frank Jolley Abstract. This paper presents an account of grooved markings found on sandstone surfaces in the Pennine upland of Yorkshire, United Kingdom, of other single examples in Scotland and the U.S.A., and of numerous unsuccessful attempts to secure an archaeological or geological explanation for them. Of particular interest are the cases where cupules and grooves appear in juxtaposition. There is a concluding discussion of some aspects which may inform a practical aetiology. Introduction of grooved surfaces have been found in around 600 The South Pennines comprise a dissected plateau square kilometres of South Pennine upland. rising to over 400 m, underlain by Namurian rocks of The Quarmby archive (WYAAS n.d.) contained a the Millstone Grit series of the Carboniferous period, in partial reference to a similar feature found on Orkney a gentle, anticlinal form; the area did not bear moving (Fig. 8). ice during the Late Devensian (final Pleistocene). The The Orkney example was found during peat- outcrops tend to fringe the upland edges. cutting at Drever’s Slap on Eday and was reported to During fieldwork to locate and record examples of the RCHAMS and subsequently placed on the Orkney rock art (Shepherd and Jolley 2011) a number of features Historic Monuments Record (RCHAMS 1981). A were identified that did not fit within the conventional site visit by D. Fraser, Department of Archaeology, canon of rock art (Figs 1 to 4). -

Tracing Human Networks In

TRACING HUMAN NETWORKS IN PREHISTORIC BALTIC EUROPE : THE INFORMATIVE POTENTIAL OF KRZYZ 7 AND DABKI 9 (POLAND) PRELIMINARY RESULTS ON BONE AND ANTLER WORKED MATERIAL Eva David To cite this version: Eva David. TRACING HUMAN NETWORKS IN PREHISTORIC BALTIC EUROPE : THE IN- FORMATIVE POTENTIAL OF KRZYZ 7 AND DABKI 9 (POLAND) PRELIMINARY RESULTS ON BONE AND ANTLER WORKED MATERIAL. [Research Report] Polish Academy of Sciences. 2007. hal-03285349 HAL Id: hal-03285349 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03285349 Submitted on 13 Jul 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SCIENTIFIC REPORT – PRELIMINARY RESULTS TRACING HUMAN NETWORKS IN PREHISTORIC BALTIC EUROPE : THE INFORMATIVE POTENTIAL OF KRZYZ 7 AND DABKI 9 (POLAND) PRELIMINARY RESULTS ON BONE AND ANTLER WORKED MATERIAL Eva DAVID* Recent archaeological investigations in Poland, at the Krzyz 7 and the Dabki 9 archaeological sites, open discussion about presence or extend of human networks in the Baltic Europe at the both 9th and 5th millenium BC. By networks, it is meant here transports or transferts of goods, ideas or technology that can possibly be highlighted by archaeological studies, by means of reconstructing human behaviours. -

Starters Mains Kemia Plates Desserts Nibbles Aperitifs Blue Man Wrap

Nibbles Aperitifs Mslalla zaytoun £3.5 Batata £4 Pomegranate prosecco Blue man marinated olives Handcut Rosemary fries or spicy wedges served Gin Martini Agroum zayton m’hams £5 with harissa mayo Aperol Spritz Bread served with homemade dips houmous and Berber toast £7 Kenyan Dawa olive tapenade Grilled goats cheese with honey and almonds Dark & Stormy Sferia £6 Choufleur makli £6 Old Fashioned Cheesy Algerian dumplings with harissa mayo Cauliflower koftas Espresso Martini Fatima’s toast £7 Sardina m’charmla £7 Algerian spiced mackerel rillets spread on flat bread Marinated anchovies served with salad £8 each or add a nibble for £12 Starters Halloumi Kaswila bel Romman £7 Crab Brik bel Toum £8 Grilled apple and halloumi topped with honey and pomegranate Crab meat in house spices wrapped in filo pastry on caramelised onion, served with carrot and rosewater served with cucumber relish and red pepper sauce Jej Charmoula bel Zaatar £8 Algerian Mixed Salad £6.50 Spicy grilled marinated chicken with speciality spices, yogurt & mint leben A raw salad with artichoke, courgettes and chickpeas sauce on naan Falafel karentita £7 Merguez A Dar bel Bisbas £8.50 Algerian falafel served with mint cucumber and tahini dressing House speciality spicy lamb sausages served with fennel, spinach and harissa Mains Khrouf bel Barkok wal Loz £14 Khodra £13 Lamb tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa. Seasonal vegetable tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa One of the most famous dishes across North Africa Zaalouk Adas Slata £11 Jej bel Mash Mash £14 Famous North African spiced tomato and grilled aubergine stew Chicken and apricot tagine served with homemade bread, couscous and harissa served with puy lentil and basil salad Algerian Bouillabaisse £14 Shakshuka £11 Famous Mediterranean dish with a North African twist, Mixed north African vegetables in a rich tomato sauce served with a cracked similar to a fish tagine with shellfish and whitefish of the day egg and baked. -

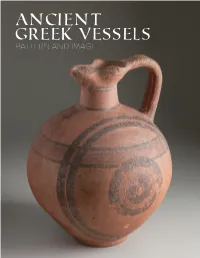

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Enumeration and Identification of Microflora in “Leben”, a Traditional Tunisian Dairy Beverage

International Food Research Journal 24(3): 927-932 (June 2017) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Enumeration and identification of microflora in “Leben”, a traditional Tunisian dairy beverage *Samet-Bali, O., Felfoul, I., Lajnaf, R., Attia, H. and Ayadi, M.A. Département de biologie, Laboratoire Valorisation, Analyse et Sécurité des Aliments (LAVASA), Ecole Nationale d’Ingénieurs de Sfax, Route de Soukra, B.P.W, 3038 Sfax, Tunisia Article history Abstract Received: 15 April 2016 The microflora involved in production of Leben, a Tunisian traditional fermented cow milk Received in revised form: product, were enumerated and identified. 15 samples of traditional Leben were analyzed. Total 10 May 2016 viable microorganisms, lactic acid bacteria (LAB), yeasts and moulds, and coliforms were Accepted: 17 May 2016 enumerated. A total of 45 LAB and 30 yeast isolates were isolated from the 15 Leben samples and identified by API 50 CHL and API 20C AUX identification systems, respectively. The LAB counts were 7.8 log10 CFU/mL, while yeast and mould counts were relatively lower (4.7 Keywords log10 CFU/ml). Low coliform numbers were encountered (1.8 log10 CFU/ml). The LAB species were identified as Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis, Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris and Fermented cow milk Leuconostoc mesenteroides. The isolated yeasts were identified as Candida krusei, Candida Lactic acid bacteria tropicalis and Candida lusitania. The most frequently isolated species was found to be Yeasts Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis (28% of total isolates), followed by Lactococcus lactis subsp. Identification cremoris (20%) and Candida krusei (18%). © All Rights Reserved Introduction product fermentation. -

Historic Furnishings Assessment, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey

~~e, ~ t..toS2.t.?B (Y\D\L • [)qf- 331 I J3d-~(l.S National Park Service -- ~~· U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Furnishings Assessment Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey Decemb r 2 ATTENTION: Portions of this scanned document are illegible due to the poor quality of the source document. HISTORIC FURNISHINGS ASSESSMENT Ford Mansion and Wic·k House Morristown National Historical Park Morristown, New Jersey by Laurel A. Racine Senior Curator ..J Northeast Museum Services Center National Park Service December 2003 Introduction Morristown National Historical Park has two furnished historic houses: The Ford Mansion, otherwise known as Washington's Headquarters, at the edge of Morristown proper, and the Wick House in Jockey Hollow about six miles south. The following report is a Historic Furnishings Assessment based on a one-week site visit (November 2001) to Morristown National Historical Park (MORR) and a review of the available resources including National Park Service (NPS) reports, manuscript collections, photographs, relevant secondary sources, and other paper-based materials. The goal of the assessment is to identify avenues for making the Ford Mansion and Wick House more accurate and compelling installations in order to increase the public's understanding of the historic events that took place there. The assessment begins with overall issues at the park including staffing, interpretation, and a potential new exhibition on historic preservation at the Museum. The assessment then addresses the houses individually. For each house the researcher briefly outlines the history of the site, discusses previous research and planning efforts, analyzes the history of room use and furnishings, describes current use and conditions, indicates extant research materials, outlines treatment options, lists the sources consulted, and recommends sourc.es for future consultation. -

Timeline from Ice Ages to European Arrival in New England

TIMELINE FROM ICE AGES TO EUROPEAN ARRIVAL IN NEW ENGLAND Mitchell T. Mulholland & Kit Curran Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts Amherst 500 Years Before Present CONTACT Europeans Arrive PERIOD 3,000 YBP WOODLAND Semi-permanent villages in which cultivated food crops are stored. Mixed-oak forest, chestnut. Slash and burn agriculture changes appearance of landscape. Cultivated plants: corn, beans, and squash. Bows and arrows, spears used along with more wood, bone tools. 6,000 YBP LATE Larger base camps; small groups move seasonally ARCHAIC through mixed-oak forest, including some tropical plants. Abundant fish and game; seeds and nuts. 9,000 YBP EARLY & Hunter/gatherers using seasonal camping sites for MIDDLE several months duration to hunt deer, turkey, ARCHAIC and fish with spears as well as gathering plants. 12,000 YBP PALEOINDIAN Small nomadic hunting groups using spears to hunt caribou and mammoth in the tundra Traditional discussions of the occupation of New England by prehistoric peoples divide prehistory into three major periods: Paleoindian, Archaic and Woodland. Paleoindian Period (12,000-9,000 BP) The Paleoindian Period extended from approximately 12,000 years before present (BP) until 9,000 BP. During this era, people manufactured fluted projectile points. They hunted caribou as well as smaller animals found in the sparse, tundra-like environment. In other parts of the country, Paleoindian groups hunted larger Pleistocene mammals such as mastodon or mammoth. In New England there is no evidence that these mammals were utilized by humans as a food source. People moved into New England after deglaciation of the region concluded around 14,000 BP. -

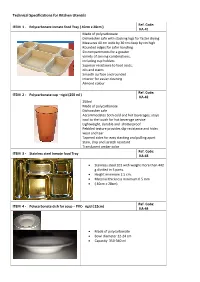

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

Estimations of Population Density for Selected Periods Between the Neolithic and AD 1800 Andreas Zimmermann University of Cologne, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Human Biology Volume 81 Issue 2 Special Issue on Demography and Cultural Article 13 Macroevolution 2009 Estimations of Population Density for Selected Periods Between the Neolithic and AD 1800 Andreas Zimmermann University of Cologne, [email protected] Johanna Hilpert University of Cologne Karl Peter Wendt University of Cologne Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol Recommended Citation Zimmermann, Andreas; Hilpert, Johanna; and Wendt, Karl Peter (2009) "Estimations of Population Density for Selected Periods Between the Neolithic and AD 1800," Human Biology: Vol. 81: Iss. 2-3, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/ humbiol/vol81/iss2/13 Estimations of Population Density for Selected Periods Between the Neolithic and AD 1800 Abstract We describe a combination of methods applied to obtain reliable estimations of population density using archaeological data. The ombc ination is based on a hierarchical model of scale levels. The necessary data and methods used to obtain the results are chosen so as to define transfer functions from one scale level to another. We apply our method to data sets from western Germany that cover early Neolithic, Iron Age, Roman, and Merovingian times as well as historical data from AD 1800. Error margins and natural and historical variability are discussed. Our results for nonstate societies are always lower than conventional estimations compiled from the literature, and we discuss the reasons for this finding. At the end, we compare the calculated local and global population densities with other estimations from different parts of the world. -

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution

On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bar-Yosef, Ofer. 1998. “On the Nature of Transitions: The Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution.” Cam. Arch. Jnl 8 (02) (October): 141. Published Version doi:10.1017/S0959774300000986 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12211496 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Cambridge Archaeological Journal 8:2 (1998), 141-63 On the Nature of Transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution Ofer Bar-Yosef This article discusses two major revolutions in the history of humankind, namely, the Neolithic and the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic revolutions. The course of the first one is used as a general analogy to study the second, and the older one. This approach puts aside the issue of biological differences among the human fossils, and concentrates solely on the cultural and technological innovations. It also demonstrates that issues that are common- place to the study of the trajisition from foraging to cultivation and animal husbandry can be employed as an overarching model for the study of the transition from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on the core areas where each of these revolutions began, the ensuing dispersals and their geographic contexts. -

Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter (1) The remnants of this government established the Republic of Ezo after losing the Boshin War. Two and a half centuries earlier, this government was founded after its leader won the Battle of Sekigahara against the Toyotomi clan. This government's policy of sakoku came to an end when Matthew Perry's Black Ships forced the opening of Japan through the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa. For ten points, name this last Japanese shogunate. ANSWER: Tokugawa Shogunate (or Tokugawa Bakufu) (2) Xenophon's Anabasis describes ten thousand Greek soldiers of this type who fought Artaxerxes II of Persia. A war named for these people was won by Hamilcar Barca and led to his conquest of Spain. Famed soldiers of this type include slingers from Rhodes and archers from Crete. Greeks who fought for Persia were, for ten points, what type of soldier that fought not for national pride, but for money? ANSWER: mercenary (prompt on descriptive answers) (3) The most prominent of the Townshend Acts not to be repealed in 1770 was a tax levied on this commodity. The Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver carried this commodity from England to the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were passed in response to the dumping of this commodity into a Massachusetts Harbor in 1773 by members of the Sons of Liberty. For ten points, identify this commodity destroyed in a namesake Boston party. ANSWER: tea (accept Tea Act; accept Boston Tea Party) (4) This location is the setting of a photo of a boy holding a toy hand grenade by Diane Arbus.