Principles of Plant Taxonomy, X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Devonian Water Canyon Formation of Northeastern Utah

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1963 The Lower Devonian Water Canyon formation of Northeastern Utah Michael E. Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Michael E., "The Lower Devonian Water Canyon formation of Northeastern Utah" (1963). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6626. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6626 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOWER DEVONIAN WATER CANYON FORMATION OF NORTHEASTERN UTAH by Michael E. Taylor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1963 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer greatly appreciates the advice and criticism offered by Dean J. Stewart Williams, Dr. Clyde T . Hardy , and Dr. Donald R. Olsen, of the Department of Geology of Utah State University. He is also grateful to his parents for their encouragement during the course of this investigation and for capable assistance with the preparation of the manuscript. Michael E. Taylor TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION o 1 General statement 1 Geolog ic setting o 3 External stratigraphic relations 4 WATER CANYON FORMATION 8 General statement 8 Card Member 9 Grassy Flat Member 13 Areal distribution 22 Paleonto logy 27 Age 33 Correlat i on 35 Environment of deposition 37 Source of detr itus 40 SUMMARY , 42 LITE RATURE CITED 43 APPENDIX 46 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. -

The Lower Cretaceous Flora of the Gates Formation from Western Canada

The Lower Cretaceous Flora of the Gates Formation from Western Canada A Shesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geological Sciences Univ. of Saska., Saskatoon?SI(, Canada S7N 3E2 b~ Zhihui Wan @ Copyright Zhihui Mian, 1996. Al1 rights reserved. National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON KlA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libraxy of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur foxmat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirernents for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ZHIRUI WAN Depart ment of Geological Sciences University of Saskatchewan Examining Commit tee: Dr. -

Life and Time of Indian Williamsonia

Life and time of Indian Williamsonia )ayasri Banerji Banerji, J 1992. Life and time of Indian Williamsonia. Palaeobotanist 40 : 245-259. The Williamsonia plant, belonging to the order Bennettitales, consists of stem-Bucklandia Presl, leaf Ptilophyllum Morris, male flower- Weltrichia Braun and female flower- Williamsonia Carruthers. This plant was perhaps a small, much branched woody tree of xerophytic environment. It co-existed alongwith extremely variable and rich flora including highly diversified plant groups from algae to gymnosperms. In India, it appeared during the marine Jurassic, proliferated and widely distributed in the Lower Cretaceous and disappeared from the vegetational scenario of Upper Cretaceous Period with the advent of angiosperms. Key-words-Bennettitales, Williamsonia, Jurassic-Cretaceous (India). jayasri Baner}i, Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, 53 University Road, Lucknow 226007, India. ri~T ~ 'lfmftq- fili'<1QQ«lf.:lQi "" om~~ "l?li'O'$i'OI<1fl \f>'f it ~ filf<1QQ«lf.:lQi qtfr if ~ ~ 3!<'flT-3!<'flT 'lTIif it ~ "lTif t W'I'T CAT-~ m, ~ ~ ~it ~fu;m;;mrr~1 ~qtm~~ <ffir ll~<'ilf4>~<'1'i"li'tfGr, "''!'''l ~~?l~Ti:t>Qi <ilf.1 'I"lT filf<1QQ«lf.:lQi ~ ~ ~ f;;ru-if.~ ~ 61'1'~dOl'h\'i if m <'IT<'1T ~ Wc:r, 3!fuq,iffiliOlT3if it ~ ¥i "IT' ~ it il'1f4ff1"1ld, it if qtfr ~ 'it, q;r tt ~ ~tl W'I'T~~'-I'<"1if~~3lT, 3Tahmm'-l'<"1if~~~-~'d"f~<f"lT'3'1f'<mm~ ~ ~ ~ ~ if qtm if if t1T"f -flT"f lIT lfllT' LIFE OF WILLIAMSONIA PLANT B. dichotoma Sharma. In B. indica Seward, the secondary wood is more compact than recent cycads In the Upper Mesozoic Era, a new group of and cycadeoids. -

Dicranophyllum Glabrum (DAWSON) STOPES, an UNUSUAL ELEMENT of LOWER WESTPHALIAN FLORAS in ATLANTIC CANADA

DICRANOPHYLLUM GLABRUM OF LOWER WESTPHALIAN FLORAS IN CANADA 7 Dicranophyllum glabrum (DAWSON) STOPES, AN UNUSUAL ELEMENT OF LOWER WESTPHALIAN FLORAS IN ATLANTIC CANADA Robert H. WAGNER Centro Paleobotánico, Jardín Botánico de Córdoba, Avda. de Linneo, s/n, 14004 Córdoba (Spain); e-mail: [email protected] Wagner, R. H. 2005. Dicranophyllum glabrum (Dawson) Stopes, an unusual element of lower Westphalian fl oras in Atlantic Canada. [Dicranophyllum glabrum (Dawson) Stopes, un elemento raro de las fl oras del Westfaliense inferior del Canadá Atlántico.] Revista Española de Paleontología, 20 (1), 7-13. ISSN 0213-6937. ABSTRACT Rare but well preserved repeatedly dichotomised leaves, apparently in a single plane, are identifi ed with Dicrano- phyllum, an unusual gymnosperm attributed to a special order, the Dicranophyllales. The specimens recorded here from the “Fern Ledges” at Saint John, New Brunswick are from lower Westphalian (Langsettian) strata, which is a low horizon for this genus, which is best known from the Stephanian and Lower Permian. Comparison is made with various species described from the Carboniferous in Europe. Keywords: Dicranophyllum, Langsettian, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia. RESUMEN Se han hallado ejemplares aislados con hojas que se dicotomizan repetidamente en lo que parece ser un solo plano en estratos del Westfaliense inferior (Langsettiense) de los “Fern Ledges” en Saint John, Nueva Brunswick. Estos ejemplares se han atribuido al género Dicranophyllum, una gimnosperma del orden de las Dicranophy llales. Se trata de un registro antiguo para este género, que se conoce sobre todo en materiales del Estefaniense y del Pérmico Inferior. Se compara con varias de las especies descritas del Carbonífero de Europa. -

The Classification of Early Land Plants-Revisited*

The classification of early land plants-revisited* Harlan P. Banks Banks HP 1992. The c1assificalion of early land plams-revisiled. Palaeohotanist 41 36·50 Three suprageneric calegories applied 10 early land plams-Rhyniophylina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina-proposed by Banks in 1968 are reviewed and found 10 have slill some usefulness. Addilions 10 each are noted, some delelions are made, and some early planls lhal display fealures of more lhan one calegory are Sel aside as Aberram Genera. Key-words-Early land-plams, Rhyniophytina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina, Evolulion. of Plant Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York-5908, U.S.A. 14853. Harlan P Banks, Section ~ ~ ~ <ltm ~ ~-~unR ~ qro ~ ~ ~ f~ 4~1~"llc"'111 ~-'J~f.f3il,!"~, 'i\'1f~()~~<1I'f'I~tl'1l ~ ~1~il~lqo;l~tl'1l, 1968 if ~ -mr lfim;j; <fr'f ~<nftm~~Fmr~%1 ~~ifmm~~-.mtl ~if-.t~m~fuit ciit'!'f.<nftmciit~%1 ~ ~ ~ -.m t ,P1T ~ ~~ lfiu ~ ~ -.t 3!ftrq; ~ ;j; <mol ~ <Rir t ;j; w -.m tl FIRST, may I express my gratitude to the Sahni, to survey briefly the fate of that Palaeobotanical Sociery for the honour it has done reclassification. Several caveats are necessary. I recall me in awarding its International Medal for 1988-89. discussing an intractable problem with the late great May I offer the Sociery sincere thanks for their James M. Schopf. His advice could help many consideration. aspiring young workers-"Survey what you have and Secondly, may I join in celebrating the work and write up that which you understand. The rest will the influence of Professor Birbal Sahni. The one time gradually fall into line." That is precisely what I did I met him was at a meeting where he was displaying in 1968. -

A Cycadean Trunk from Uryu District, Hokkaido, Japan

Title A Cycadean Trunk from Uryu District, Hokkaido, Japan Author(s) Tanai, Toshimasa Citation Journal of the Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University. Series 4, Geology and mineralogy, 10(3), 545-550 Issue Date 1960-03 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/35919 Type bulletin (article) File Information 10(3)_545-550.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP A CYCADEAN TRUNK geROM IVRW DXSTRXC Er, ffKOKKAXDO, ]APAN By Toshimasa TANAI Contyibution from the ])epartment of Geology and Mineralogy, Faeulty o£ Seience, Hokkaido University, No. 8e2 The fiyst occurrenee of a Cyeadeaii trunl< in Japan was reported by A. KRySUToFovlcff (1920) from the neighbourhood of Takikawa-machi, Sorachi distriet, Hokkaid6. Sinee then, several speeimens have been reported from various loealities from KyGsha to Saghalin. These Cycadear; trunks from Japan and Saghalin were found in the Late Cretaceeus, though most of the European and Ameriean fossi} trunks were fyom the Early Cretaceeus-Jurassic sediments. Fttrthermore, a remarl<able fea- ttu'e of the Japanese Cycadean tyuRks is the absenee o£ any fertile-shoots among the leaf-bases, while many of the European and American speei- mens generally exhibit on a single stem numerous fioweys borne at the ends of short lateral branehes which projeet hardly at all beyoBd the general level of the armour of persistent }eaf-bases. The present material was found from the terraee deposits along the Tachibetsu river near Numata-maehi, Uryti district, Hokkaid6 by A. NAI<AyAMA, who is }lving there ([['ext-fig. 1). It is evidently a bouider transported by river-flow from the upper course of the Tachibetsti river. -

Diversity and Evolution of the Megaphyll in Euphyllophytes

G Model PALEVO-665; No. of Pages 16 ARTICLE IN PRESS C. R. Palevol xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Palevol w ww.sciencedirect.com General palaeontology, systematics and evolution (Palaeobotany) Diversity and evolution of the megaphyll in Euphyllophytes: Phylogenetic hypotheses and the problem of foliar organ definition Diversité et évolution de la mégaphylle chez les Euphyllophytes : hypothèses phylogénétiques et le problème de la définition de l’organe foliaire ∗ Adèle Corvez , Véronique Barriel , Jean-Yves Dubuisson UMR 7207 CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, centre de recherches en paléobiodiversité et paléoenvironnements, 57, rue Cuvier, CP 48, 75005 Paris, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recent paleobotanical studies suggest that megaphylls evolved several times in land plant st Received 1 February 2012 evolution, implying that behind the single word “megaphyll” are hidden very differ- Accepted after revision 23 May 2012 ent notions and concepts. We therefore review current knowledge about diverse foliar Available online xxx organs and related characters observed in fossil and living plants, using one phylogenetic hypothesis to infer their origins and evolution. Four foliar organs and one lateral axis are Presented by Philippe Taquet described in detail and differ by the different combination of four main characters: lateral organ symmetry, abdaxity, planation and webbing. Phylogenetic analyses show that the Keywords: “true” megaphyll appeared at least twice in Euphyllophytes, and that the history of the Euphyllophytes Megaphyll four main characters is different in each case. The current definition of the megaphyll is questioned; we propose a clear and accurate terminology in order to remove ambiguities Bilateral symmetry Abdaxity of the current vocabulary. -

Cycadeoidea Saucer Shaped Structure

1 | P a g e —The bracts open up at maturity to form a broad Cycadeoidea saucer shaped structure. Systematic Position —There are about 20 pinnate microsporophylls Class: Cycadopsida arranged in a whorl at the base of ovuliferous receptacle. Order: Cycadeoidales/Bennettitales —Two rows of kidney shaped synangia are borne on Family: Cycadeoidaceae the inner surface of each pinnule of a Genus: Cycadeoidea microsporophyll. Microsporophylls were united at the base and free above which is comparable to the segments of an orange. Distribution: Cycadeoidea is the only genus under — Each synangium bore 20-30 tubular pollen sacs the family Cycadeoidaceae and has a wide or sporangia containing monocolpate (monosulcate) geographical distribution, especially in North pollen grains. America, Europe and India during Upper Jurassic to — The synangium consisted of palisade like cells and Upper Cretaceous. dehisced by means of an apical slit into two equal halves. External Features: — Numerous tiny stalked orthotropous ovules are —The plants have ovoid or short columnar which present in group at the conical or dome shaped apex were unbranched or apparently branched. The of the fertile shoot. They are interspersed with trunks were massive, not more than 1 m in length interseminal scales. Their number is equal to the and 60 cm in diameter. number of ovules. Their heads are enlarged into a —The surface of the stem is covered with prominent club which are fused with the adjoining interseminal rhomboidal leaf bases and multicellular hairs in scales in such a manner that it forms a continuous between them. surface layer with openings. Through the openings — The trunk had spirally arranged leaf bases micropyles project. -

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

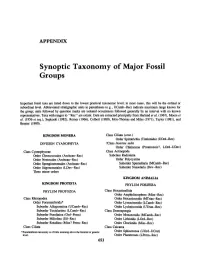

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Type of the Paper (Article

life Article Dynamics of Silurian Plants as Response to Climate Changes Josef Pšeniˇcka 1,* , Jiˇrí Bek 2, Jiˇrí Frýda 3,4, Viktor Žárský 2,5,6, Monika Uhlíˇrová 1,7 and Petr Štorch 2 1 Centre of Palaeobiodiversity, West Bohemian Museum in Pilsen, Kopeckého sady 2, 301 00 Plzeˇn,Czech Republic; [email protected] 2 Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology, Geological Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rozvojová 269, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] (J.B.); [email protected] (V.Ž.); [email protected] (P.Š.) 3 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Kamýcká 129, 165 21 Praha 6, Czech Republic; [email protected] 4 Czech Geological Survey, Klárov 3/131, 118 21 Prague 1, Czech Republic 5 Department of Experimental Plant Biology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Viniˇcná 5, 128 43 Prague 2, Czech Republic 6 Institute of Experimental Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, v. v. i., Rozvojová 263, 165 00 Prague 6, Czech Republic 7 Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Albertov 6, 128 43 Prague 2, Czech Republic * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-733-133-042 Abstract: The most ancient macroscopic plants fossils are Early Silurian cooksonioid sporophytes from the volcanic islands of the peri-Gondwanan palaeoregion (the Barrandian area, Prague Basin, Czech Republic). However, available palynological, phylogenetic and geological evidence indicates that the history of plant terrestrialization is much longer and it is recently accepted that land floras, producing different types of spores, already were established in the Ordovician Period. -

Bennettitales) from the Bajocian of Yorkshire

Int. J. Plant Sci. 170(9):1195–1200. 2009. Ó 2009 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/2009/17009-0007$15.00 DOI: 10.1086/605873 THE POLLEN ULTRASTRUCTURE OF WILLIAMSONIELLA CORONATA THOMAS (BENNETTITALES) FROM THE BAJOCIAN OF YORKSHIRE Natalia Zavialova,1,* Johanna van Konijnenburg-van Cittert,y and Michael Zavadaz *A. A. Borissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyusnaya 123, Moscow 117647, Russia; yInstitute of Environmental Biology, Faculty of Science, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands, and the National Natural History Museum ‘‘Naturalis,’’ Leiden, The Netherlands; and zDepartment of Biological Sciences, East Tennessee State University, Box 70703, Johnson City, Tennessee 37614, U.S.A. The exine ultrastructure of Williamsoniella coronata Thomas from the Bajocian of Yorkshire (United Kingdom) was investigated with light, scanning electron, and transmission electron microscopy. The pollen averages 16.5 mm along its short axis and 24.5 mm along its long axis and is monosulcate, and the nonapertural sculpturing is distinctly verrucate. The pollen wall is homogeneous, and the sulcus membrane is composed of thin exine with scattered small granules. The pollen grains differ in exine sculpturing and pollen wall ultrastructure from pollen grains of the bennettitalean taxa Cycadeoidea dacotensis (MacBride) Ward and Leguminanthus siliquosis (Leuthardt) Kraeusel. They are similar to dispersed pollen grains of Granamonocolpites luisae Herbst from the Triassic Chinle Formation of the United States, supporting the bennettitalean affinity of these dispersed pollen grains. The Bennettitales are palynologically characterized by monosulcate ‘‘boat-shaped’’ pollen with a homogeneous or granular pollen wall ultrastructure. Keywords: exine sculpture, exine ultrastructure, Bennettitales, Jurassic. -

Egu Poster1.Cdr

PPPalaalleeeoooeeennnvivivirrrooonnmnmmeeennntttsss ooofff EEEaraarrlllyyy DeDeDevvvoooninniianaann pplpllaananntttsss anandandd fififishshsh iiinnn ttthehhee CamCamCamppbpbbeeelllllltttooonnn FFFooorrrmmmaaatttiiiooonn,n,, NNNeeewww BBBrrrunuunnssswiwiwiccck,k,k, CaCaCannadnadaadaa::: iiinnnvvvaasiasisiooonnn ooofff ttthehhee lllandaandnd aaattt aaa ccclllaassiassissiccc lllooocccaalalliiitttyyy Fig. 4 - Schematic representation of the fossiliferous lower formational contact Fig. 5 - Schematic representation of section I Acanthodian Chondrichthyan Section I (Fig. 5): A sandy deltaic Syntheses Placoderm Ostracoderm Eurypterid system that microfossil evidence WESTERN BELT Ostracod Val d’Amour Gastropod Fm flow-banded suggests may be brackish. Most S N Lower contact (Fig. 4): The S rhyolite N Section V Section VI interbedded tabular sandstones massive grey t t Campbellton Fm breccia and fissure-fills specimens are preserved in and mudstones with sandstone channels mudstones Fig. 3 - Geologic map of the Campbellton Formation and surroundings illustrating MUD GRAVEL MUD GRAVEL fissured rhyolite surface onmen onmen SAND SAND y y an an ale (m) ale (m) vir vir vc obb outcrop extent, paleocurrents, and locations of stratigraphic sections. vfmvc obb vfm cla silt gr pebb c boul cla silt gr pebb c boul interdistributary mudstone c Sc Lithology Sc Lithology f Structures f c Structures En En 100 of the Val d’Amour Formation was submerged providing a Section I Section II -66°44' -66°40' -66°36' -66°32' -66°28' -66°24' t t Legend: Bonaventure Fm n=3 930 including a large Pterygotus molt and the articulated MUD GRAVEL MUD GRAVEL Outcrop Campbellton Fm n=4 90 shelter for aquatic organisms. This surface was filled by micrite onmen onmen SAND SAND y y City an an 48°04' La Garde Fm ale (m) ale (m) 6 vir vir III vc obb vfm vfmvc obb cla silt gr pebb c boul cla silt gr pebb c boul VI 920 Sc Lithology f c Structures Sc Lithology f c Structures Paleocurrents 70 En En Val d’Amour Fm braincase of the chondrichthyan Doliodus problematicus.