Resilience Through Engaging Citizens with Urban Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION and a Number of Corridors As Illustrated in Figure 3

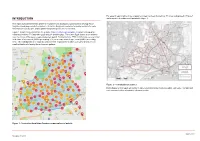

For ease of reporting the whole engagement area has been divided into 37 zones as displayed in Figure 2 INTRODUCTION and a number of corridors as illustrated in Figure 3. This report summarises the first phase of engagement as Stockport Council looks to develop Active Neighbourhood proposals in the Heaton’s. An Active Neighbourhood aims to enable residents to make short trips on foot, by cycle and by public transport in preference to car travel. Figure 1 shows a screenshot from the website (https://heatons.commonplace.is/) which was open for comments between 7th September 2020 and 23rd October 2020. There were 5228 visitors to the website over the course of the seven-week engagement period. During this time, 7788 contributions were recorded in the form of a comment (1298 representing 17%) or an expression of agreement (6490 representing 83%). The contributions were made by a total of 1331 respondents of which 553 subscribed to receive email notifications informing them of project updates. Figure 2 - Consultation area zones Each chapter of this report will contain a table summarising the comments within each zone / corridor and each comment will be allocated a reference number. Figure 1 - Screenshot from https://heatons.commonplace.is/ website March 2021 Stockport Council Figure 3 - Consultation area corridors March 2021 Stockport Council ZONE 1: SOUTH OF A5145 DIDSBURY ROAD AND WEST OF STATION ROAD & VALE ROAD This chapter reports on pins dropped to the south of the A5145 Didsbury Road and to the west of Station Road & Vale Road. The zone includes Heaton Mersey Industrial Estate, Embankment Business Park, and Heaton Mersey Valley Golf Course. -

Davenport Green to Ardwick

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | MA07 MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H10 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick H10 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

20 21 22 23 24 25 Trial Planters KEY Phase 2 Area

No part of this drawing or data file may be reproduced without the prior written permission of the Strategic Director of Highways, Transport & Engineering or approved representative. Contains OS Data © Crown copyright and database rights 2017PINK BANK Ordnance Survey 100019568. 587b RAINFORTH STREET Gore 111 19 75 10 327 Church 21 589 Brook DICKENSON ROAD 1 5 LANE 39 606 23 65 15 7 20 4a Works 40 25 55 86 608 SHERRINGTON STREET 110 9 53 2 8 31 15 33 MONKTON AVENUE 352 13 47.9m 53 19 1 38 317 to 319 612 KENTON AVENUE 6 9 24 610 1 to 23 BIRCH LANE PROUT STREET 6 Shelter 11 72 13 315 CHURTON ROAD Hall 28 614 13 593 1 HATTON STREET 202 31 19 2 13 13 Birch Longsight Business Park 616 13 13 15 29 35 62 MACKENZIE STREET 1 5 14 4 THORNHOLME 121 166 Court 2 14 309 618 338 17 CALBOURNE CRESCENT 2 2 189 46 48 6 59 35 118 599 14 10 2 336 STOCKPORT ROAD Path (um) FENMORE AVENUE Garage 48 81 12 36 5 13 2 DARRAS ROAD MP 0.75 212 61 9 14 37 63 HEXHAM 2a 23 16 29 4 to 8 CLARENCE ROAD 31 123 69 11 10 324 1 42 21 108 26 25 14 59 22 620 82 1a 322 23 120 24 13 38 74 10 Mega Plaza 622 307 4 to 1 51 50 Roby United 26 72 13 8 23 50 7 141 624 Reformed Church 13 1b 47.0m 41 33 137 2 Bank TALLIS STREET 224 143 1 6 1 30 62 195 BARNBY STREET 14 HOPKINS STREET 139 62 ROAD 312 18 1 CLOSE 12 39 6 20 31 195a 41 3 176 1 52 47.4m PATEY STREET 8 28 628 26 1 34 135 20 135 13 128 BARNARD ROAD 11 234 1 25 2 42 60.6m 25 8 55.2m MEADE GROVE 60 33 PO 2 1 26 32 75 2 81 27 1 39 83 22 12 14 45 131 2 32 RUSHFORD STREET 1 20 41 SWAYFIELD AVENUE TRUST ROAD Surgery ALBERT PLACE 60 23 -

Area Footpath Secretary

MANCHESTER AND Manchester and Salford SALFORD Local Group Newsletter and Walks (M & S Ramblers) No 42 September 2019 AGM Saturday 2nd November. Monton Unitarian Church Hall, Monton Green, Eccles M30 8AP Meet at Dukes Drive car park at 11am for walk along Loop line and around Worsley Back at the Church Hall for 12.30pm for lunch Meeting at 1.30pm close at 3.30/4 pm Socials October 22ndGeology and stones. The walk and talk, 'Rocks of Modern Manchester' looking at the variety of materials used to build some of the magnificent buildings in the city. It is led by our own Pia and will be very interesting. .We will meet at 11am in St Peter's Square under the colonnade outside Central Library. November 26th Guided walk and talk through Worsley looking at the impact of the industrial revolution through canals and bridges. Then bringing it right up to date with a look at the site of the RHS gardens (hopefully one of our tours for 2020). This will be led by Emma Fox. December 16th Christmas Social.Meeting at the Market and the Paramount on Oxford Road. More details for November and December nearer the time. Black Men Walking Another chance to see this excellent play. Some of us saw it at Royal Exchange a couple of years ago. Written by the son of two of our members and based on Walking group set up by Maxwell Ayamba, who many of us have heard speak at Kinder anniversary events. http://www.coliseum.org.uk/plays/black-men-walking In Oldham 24-26th October and touring. -

Final Evaluation Report

From Grey to Green 2012 to 2015 – Evaluation Report From Grey to Green Final Evaluation 2012-15 1 October 2015 From Grey to Green 2012 to 2015 – Evaluation Report CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 3 2. WHAT WE WATE TO HAPPEN .......................................................................................................... 5 A AIMS OF THE ROJECT…………………………….………………………………………………………………………………5 B WHY WE WANTED TO DO THE PROJECT .................................................................................... 5 C WHAT WE PLANNED TO DO ....................................................................................................... 6 D THE DIFFERENCE WE EXPECTED IT TO MAKE ........................................................................... 11 3. WHAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED ........................................................................................................ 12 A PROJECT MANAGEMENT ISSUES .............................................................................................. 12 B BACKGROUND TO EVALUATION METHODS USED ................................................................... 12 C THE DIFFERENCE THE PROJECT MADE ..................................................................................... 14 4. REVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 59 A WHAT WORKED WELL AND WHY ............................................................................................ -

Report on Cash Grants Programme to Resources and Governance

Manchester City Council Item 8 Resources and Governance Overview and Scrutiny Committee 16 December 2010 Manchester City Council Report for Information Report To: Resources and Governance Overview and Scrutiny Committee - 16 December 2010 Subject: Cash Grants Programme Report Of: Chief Executive ___________________________________________________________ Purpose of Report: To provide Members with feedback on the implementation of the Cash grants scheme over the last three years, with specific reference to how the scheme has enhanced community engagement in wards. Recommendation For Members to note the content of this report. Financial Consequences for the Revenue and Capital Budgets The current Cash grants programme comprised this year of main stream £1,260,000 plus additional £180,000 from WNF Revenue. Contact Officers Maria Boylan - Strategy Leader, Corporate Performance Tel: 0161 234 3998 [email protected] Jolanta Shields – Area Co-ordination and Third Sector Team - 0161 234 [email protected] Background Documents None Wards Affected All 32 Manchester City Council Item 8 Resources and Governance Overview and Scrutiny Committee 16 December 2010 Introduction 1.1 Manchester City Council’s Cash grant programme was set up in 1999, initially as a one – off scheme to support community projects that contributed to the objectives of the Bright and Clean campaign or the Crime and Disorder Reduction Strategy. Following the popularity and success of the scheme, the City Council agreed to continue providing support for this programme with the budget per ward rising from an initial £25,000 to £45,000 in 2010. Since this funding scheme was first launched, the Council has made an investment of approximately £8 million in 32 wards in Manchester. -

Manchester City Council

MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL REPORT FOR RESOLUTION COMMITTEE EXECUTIVE DATE 21 NOVEMBER 2007 SUBJECT LOCAL NATURE RESERVE DECLARATION: BOGGART HOLE CLOUGH AND HIGHFIELD COUNTRY PARK REPORT OF HEAD OF ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES HEAD OF LEISURE AND SPORTS PURPOSE OF REPORT To seek the approval of the Executive Committee to declare two sites in Manchester, Boggart Hole Clough and Highfield Country Park, as Local Nature Reserves. RECOMMENDATIONS 1. To declare the area shown outlined on the “Location map of Boggart Hole Clough” (Appendix 1) as the Boggart Hole Clough Local Nature Reserve. 2. To declare the area shown outlined on the “Location map of Highfield Country Park” (Appendix 2) as the Highfield Country Park Local Nature Reserve. Financial Consequences for the Revenue Budget The proposal has no implications for the City Council’s revenue budget. Financial Consequences for the Capital Budget The proposal has no implications for the City Council’s capital budget. Contact Officers Rachel Christie – Head of Environmental Services 800 4916 [email protected] Eamonn O’Rourke – Head of Leisure and Sports 878 2451 e.o’[email protected] Sarah Davies – Green City Project Director 800 3361 [email protected] Jon Follows – Green City Project Officer 800 1869 [email protected] Background Documents The Boggart Hole Clough and Highfield Country Park Management Plans are available from Room 6019 in the Town Hall Extension. Wards Affected Charlestown Levenshulme Implications for: Anti poverty Equal Opportunities Environment Employment No No Yes No 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 On the 13th April 2005, the Executive Committee approved and adopted the Manchester Biodiversity Strategy. -

Integrated Assessment (Appendices) Atkins

Greater Manchester Transport Strategy 2040 and Delivery Plan 1 (2016/17 - 2021/22) Integrated Assessment Report Appendices Transport for Greater Manchester June 2016 1 GM Transport Strategy 2040 and Delivery Plan 1 Integrated Assessment (Appendices) Atkins Notice This document and its contents have been prepared and are intended solely for Transport for Greater Manchester’s information and use in relation to the Integrated Assessment of the Greater Manchester 2040 Transport Strategy and Delivery Plan 1. Atkins Ltd assumes no responsibility to any other party in respect of or arising out of or in connection with this document and/or its contents. This report has been prepared by sustainability specialists and does not purport to provide legal advice. Document history Job number: 5144920 Document ref: IA Report Appendices Revision Purpose description Originated Checked Reviewed Authorised Date Rev 1.0 Partial draft for comments Sustainability P McEntee C West C West 31/03/16 team Rev 2.0 Full draft for comment P McEntee C West C West C West 20/06/16 Rev 3.0 Final for consultation P McEntee P McEntee C West C West 29/06/16 Client signoff Client Transport for Greater Manchester Project Greater Manchester Transport Strategy2040 and Delivery Plan 1 (2016/17 – 2021/22) Integrated Assessment Document title Integrated Assessment Report (Appendices) Job no. 5144920 Copy no. Document IA Report Appendices reference 2 GM Transport Strategy 2040 and Delivery Plan 1 Integrated Assessment (Appendices) Atkins Table of contents Appendix A. Responses to the IA Key Sustainability Issues Technical Note 4 Appendix B. Policy documents reviewed for the IA 12 Appendix C. -

Ecological Assessment

MATTHEWS LANE GORTON, MANCHESTER ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT TEP Genesis Centre Birchwood Science Park Warrington WA3 7BH Tel: 01925 844004 Email: [email protected] www.tep.uk.com Offices in Warrington, Market Harborough, Gateshead, London and Cornwall PLANNING I DESIGN I ENVIRONMENT Matthews Lane Gorton, Manchester Ecological Assessment Document Title Ecological Assessment Prepared for Laing O'Rourke Northern Ltd Prepared by TEP - Warrington Document Ref 6150.001 Author Fleur Wilson Date January 2017 Checked Emma Pickering Approved Lee Greenhough Amendment History Check / Modified Version Date Approved Reason(s) issue Status by by Matthews Lane Gorton, Manchester Ecological Assessment CONTENTS PAGE Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 2 1.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Site Description ....................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Methods .................................................................................................................. 5 4.0 Results .................................................................................................................... 7 5.0 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ 16 6.0 Recommendations ............................................................................................... -

Biodiversity Action Plan (2003) Followed on of Manchester

Biodiversity Strategy 2005 draft Executive Summary Introduction The word biodiversity comes from the phrase ‘biological diversity’. In its simplest term biodiversity means the whole variety of life on Earth. It includes all plants and animals, their habitats and the factors that link them to each other and their surroundings. It is not restricted to rare or threatened species and habitats but includes the whole of the natural world from the commonplace to the critically endangered. We all have a part to play in safeguarding the In the UK it was identified that a strategic Earth’s biodiversity. Therefore action needs to be approach was needed to halt the loss of taken, at both a local and global level, before our biodiversity. Therefore in 1994 the UK Biodiversity biodiversity disappears for good. The benefits Action Plan was produced which detailed the of biodiversity are endless, but include: UK’s commitment to biodiversity and how it should be delivered. The Greater Manchester Learning about and enjoying the wildlife Biodiversity Action Plan (2003) followed on of Manchester. This makes an important which focused the aims of the UK Biodiversity contribution to our quality of life, health Action Plan at a Greater Manchester level. and spiritual well being. Plants, animals and habitats enrich our From the Greater Manchester Biodiversity everyday lives as they produce the Action Plan (GMBAP) it became apparent that necessary ingredients for all life to exist. there was a need for a strategy to focus at the Without conserving biodiversity, we will city of Manchester level, detailing the habitats pass to our successors a planet that is and species present along with identifying markedly poorer than the one we were the specific priorities for Manchester. -

INTRODUCTION and a Number of Corridors As Illustrated in Figure 3

For ease of reporting the whole engagement area has been divided into 37 zones as displayed in Figure 2 INTRODUCTION and a number of corridors as illustrated in Figure 3. This report summarises the first phase of engagement as Stockport Council looks to develop Active Neighbourhood proposals in the Heaton’s. An Active Neighbourhood aims to enable residents to make short trips on foot, by cycle and by public transport in preference to car travel. Figure 1 shows a screenshot from the website (https://heatons.commonplace.is/) which was open for comments between 7th September 2020 and 23rd October 2020. There were 5228 visitors to the website over the course of the seven-week engagement period. During this time, 7788 contributions were recorded in the form of a comment (1298 representing 17%) or an expression of agreement (6490 representing 83%). The contributions were made by a total of 1331 respondents of which 553 subscribed to receive email notifications informing them of project updates. Figure 2 - Consultation area zones Each chapter of this report will contain a table summarising the comments within each zone / corridor and each comment will be allocated a reference number. Figure 1 - Screenshot from https://heatons.commonplace.is/ website March 2021 Stockport Council Figure 3 - Consultation area corridors March 2021 Stockport Council STATION ROAD CORRIDOR This chapter reports on pins dropped in and around Station Road which links the A5145 Didsbury Road to Craig Road & Vale Road. It also forms a junction with Green Pastures as shown in Figure 4. Figure 5 - Home postcode boundaries of respondents who provided comments in the Station Road corridor Figure 4 - Station Road corridor Pins 6 and 7 are also applicable to Zone 1 and are numbered 11 and 12, respectively. -

Executive 19 November 2008 Local Nature Reserve Declaration

Manchester City Council Item 11 Executive 19 November 2008 MANCHESTER CITY COUNCIL REPORT FOR RESOLUTION REPORT TO Executive DATE 19 November 2008 SUBJECT Local Nature Reserve Declaration: Stenner Woods and Millgate Fields REPORT OF Head of Environmental Services Head of Leisure and Sports PURPOSE OF REPORT To seek the approval of the Executive Committee to declare Stenner Woods and Millgate Fields as a Local Nature Reserve. RECOMMENDATIONS 1. To declare the area shown on the location map of Stenner Woods and Millgate Fields ( Appendix1) outlined in red and excluding the building to the west of Millgate Farm at grid reference 384151,389642 as the Stenner Woods and MIllgate Fields Local Nature Reserve. Financial Consequences for the Revenue Budget The proposal has no implications for the City Council’s revenue budget. Financial Consequences for the Capital Budget The proposal has no implications for the City Council’s capital budget. Contact Officers Rachel Christie – Head of Environmental Services 800 4916 [email protected] Eamonn O’Rourke – Head of Leisure and Sports 878 2451 e.o’[email protected] Dave Barlow –Environmental Engagement Manager 878 2755 [email protected] Alex Krause – Mersey Valley Warden Ecologist 881 5639 [email protected] Manchester City Council Item 11 Executive 19 November 2008 Background Documents The Stenner Woods and Millgate Fields management plans are available from Room 6019 in the Town Hall Extension. Wards Affected Didsbury West Didsbury East Implications for: Anti poverty Equal Opportunities Environment Employment No No Yes No Manchester City Council Item 11 Executive 19 November 2008 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 On the 13th April 2005, Executive Committee approved and adopted the Manchester Biodiversity Strategy.