Assessing the Accuracy of Tree Diameter Measurements Collected at a Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dial Caliperscalipers at the Conclusion of This Presentation, You Will Be Able To…

Forging new generations of engineers DialDial CalipersCalipers At the conclusion of this presentation, you will be able to… identify four types of measurements that dial calipers can perform. identify the different parts of a dial caliper. accurately read an inch dial caliper. DialDial CalipersCalipers GeneralGeneral InformationInformation DialDial CalipersCalipers are arguably the most common and versatile of all the precision measuring tools. Engineers, technicians, scientists and machinists use precision measurement tools every day for: • analysis • reverse engineering • inspection • manufacturing • engineering design DialDial CalipersCalipers FourFour TypesTypes ofof MeasurementsMeasurements Dial calipers are used to perform four common measurements on parts… 1. Outside Diameter/Object Thickness 2. Inside Diameter/Space Width 3. Step Distance 4. Hole Depth OutsideOutside MeasuringMeasuring FacesFaces These are the faces between which outside length or diameter is measured. InsideInside MeasuringMeasuring FacesFaces These are the faces between which inside diameter or space width (i.e., slot width) is measured. StepStep MeasuringMeasuring FacesFaces These are the faces between which stepped parallel surface distance can be measured. DepthDepth MeasuringMeasuring FacesFaces These are the faces between which the depth of a hole can be measured. Note: Work piece is shown in section. Dial Caliper shortened for graphic purposes. DialDial CalipersCalipers NomenclatureNomenclature A standard inchinch dialdial calipercaliper will measure slightly more than 6 inches. The bladeblade scalescale shows each inch divided into 10 increments. Each increment equals one hundred thousandths (0.100”). Note: Some dial calipers have blade scales that are located above or below the rack. BladeBlade The bladeblade is the immovable portion of the dial caliper. SliderSlider The sliderslider moves along the blade and is used to adjust the distance between the measuring surfaces. -

Check Points for Measuring Instruments

Catalog No. E12024 Check Points for Measuring Instruments Introduction Measurement… the word can mean many things. In the case of length measurement there are many kinds of measuring instrument and corresponding measuring methods. For efficient and accurate measurement, the proper usage of measuring tools and instruments is vital. Additionally, to ensure the long working life of those instruments, care in use and regular maintenance is important. We have put together this booklet to help anyone get the best use from a Mitutoyo measuring instrument for many years, and sincerely hope it will help you. CONVENTIONS USED IN THIS BOOKLET The following symbols are used in this booklet to help the user obtain reliable measurement data through correct instrument operation. correct incorrect CONTENTS Products Used for Maintenance of Measuring Instruments 1 Micrometers Digimatic Outside Micrometers (Coolant Proof Micrometers) 2 Outside Micrometers 3 Holtest Digimatic Holtest (Three-point Bore Micrometers) 4 Holtest (Two-point/Three-point Bore Micrometers) 5 Bore Gages Bore Gages 6 Bore Gages (Small Holes) 7 Calipers ABSOLUTE Coolant Proof Calipers 8 ABSOLUTE Digimatic Calipers 9 Dial Calipers 10 Vernier Calipers 11 ABSOLUTE Inside Calipers 12 Offset Centerline Calipers 13 Height Gages Digimatic Height Gages 14 ABSOLUTE Digimatic Height Gages 15 Vernier Height Gages 16 Dial Height Gages 17 Indicators Digimatic Indicators 18 Dial Indicators 19 Dial Test Indicators (Lever-operated Dial Indicators) 20 Thickness Gages 21 Gauge Blocks Rectangular Gauge Blocks 22 Products Used for Maintenance of Measuring Instruments Mitutoyo products Micrometer oil Maintenance kit for gauge blocks Lubrication and rust-prevention oil Maintenance kit for gauge Order No.207000 blocks includes all the necessary maintenance tools for removing burrs and contamination, and for applying anti-corrosion treatment after use, etc. -

Thematic Forest Dictionary

Elżbieta Kloc THEMATIC FOREST DICTIONARY TEMATYCZNY SŁOWNIK LEÂNY Wydano na zlecenie Dyrekcji Generalnej Lasów Państwowych Warszawa 2015 © Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych ul. Grójecka 127 02-124 Warszawa tel. 22 18 55 353 e-mail: [email protected] www.lasy.gov.pl © Elżbieta Kloc Konsultacja merytoryczna: dr inż. Krzysztof Michalec Konsultacja i współautorstwo haseł z zakresu hodowli lasu: dr inż. Maciej Pach Recenzja: dr Ewa Bandura Ilustracje: Bartłomiej Gaczorek Zdjęcia na okładce Paweł Fabijański Korekta Anna Wikło ISBN 978-83-63895-48-8 Projek graficzny i przygotowanie do druku PLUPART Druk i oprawa Ośrodek Rozwojowo-Wdrożeniowy Lasów Państwowych w Bedoniu TABLE OF CONTENTS – SPIS TREÂCI ENGLISH-POLISH THEMATIC FOREST DICTIONARY ANGIELSKO-POLSKI TEMATYCZNY SŁOWNIK LEÂNY OD AUTORKI ................................................... 9 WYKAZ OBJAŚNIEŃ I SKRÓTÓW ................................... 10 PLANTS – ROŚLINY ............................................ 13 1. Taxa – jednostki taksonomiczne .................................. 14 2. Plant classification – klasyfikacja roślin ............................. 14 3. List of forest plant species – lista gatunków roślin leśnych .............. 17 4. List of tree and shrub species – lista gatunków drzew i krzewów ......... 19 5. Plant morphology – morfologia roślin .............................. 22 6. Plant cells, tissues and their compounds – komórki i tkanki roślinne oraz ich części składowe .................. 30 7. Plant habitat preferences – preferencje środowiskowe roślin -

Planting Power ... Formation in Portugal.Pdf

Promotoren: Dr. F. von Benda-Beckmann Hoogleraar in het recht, meer in het bijzonder het agrarisch recht van de niet-westerse gebieden. Ir. A. van Maaren Emeritus hoogleraar in de boshuishoudkunde. Preface The history of Portugal is, like that of many other countries in Europe, one of deforestation and reafforestation. Until the eighteenth century, the reclamation of land for agriculture, the expansion of animal husbandry (often on communal grazing grounds or baldios), and the increased demand for wood and timber resulted in the gradual disappearance of forests and woodlands. This tendency was reversed only in the nineteenth century, when planting of trees became a scientifically guided and often government-sponsored activity. The reversal was due, on the one hand, to the increased economic value of timber (the market's "invisible hand" raised timber prices and made forest plantation economically attractive), and to the realization that deforestation had severe impacts on the environment. It was no accident that the idea of sustainability, so much in vogue today, was developed by early-nineteenth-century foresters. Such is the common perspective on forestry history in Europe and Portugal. Within this perspective, social phenomena are translated into abstract notions like agricultural expansion, the invisible hand of the market, and the public interest in sustainably-used natural environments. In such accounts, trees can become gifts from the gods to shelter, feed and warm the mortals (for an example, see: O Vilarealense, (Vila Real), 12 January 1961). However, a closer look makes it clear that such a detached account misses one key aspect: forests serve not only public, but also particular interests, and these particular interests correspond to specific social groups. -

Forestry Commission Bulletin: Forestry Practice

HMSO £3.50 net Forestry Commission Bulletin Forestry Commission ARCHIVE Forestry Practice FORESTRY COMMISSION BULLETIN No. 14 FORESTRY PRACTICE A Summary of Methods of Establishing, Maintaining and Harvesting Forest Crops with Advice on Planning and other Management Considerations for Owners, Agents and Foresters Edited by O. N. Blatchford, B.Sc. Forestry Commission LONDON: HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE © Crown copyright 1978 First published 1933 Ninth Edition 1978 ISBN011 7101508 FOREWORD This latest edition ofForestry Practice sets out to give a comprehensive account of silvicultural practice and forest management in Britain. Since the first edition, the Forestry Commission has produced a large number of Bulletins, Booklets, Forest Records and Leaflets covering very fully a wide variety of forestry matters. Reference is made to these where appropriate so that the reader may supplement the information and guidance given here. Titles given in the bibliography at the end of each chapter are normally available through a library and those currently in print are listed in the Forestry Commission Catalogue of Publications obtainable from the Publications Officer, Forest Research Station, Alice Holt Lodge, Wrecclesham, Famham, Surrey. Research and Development Papers mainly unpriced may be obtained only from that address. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The cover picture and all the photographs are from the Forestry Commission’s photographic collection. Fair drawings of diagrams were made, where appropriate, by J. Williams, the Commission’s Graphics Officer. CONTENTS Chapter 1 SEED SUPPLY AND COLLECTION Page Seed sources . 1 Seed stands 1 Seed orchards 3 Collection of seed 3 Storage of fruit and seeds 3 Conifers . 3 Broadleaved species 3 Seed regulations 3 Bibliography 4 Chapter 2 NURSERY PRACTICE Objectives . -

Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals, 2001 Workshop Proceedings

Natural Resource Network Connecting Research, Teaching and Outreach 2001 Workshop Proceedings Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals Caroline A. Fox Research and Demonstration Forest Hillsborough, NH Sampling & Management of Coarse Woody Debris- October 12 Getting the Most from Your Cruise- October 19 Cruising Hardware & Software for Foresters- November 9 UNH Cooperative Extension 131 Main Street, 214 Nesmith Hall, Durham, NH 03824 The Caroline A. Fox Research and Demonstration Forest (Fox Forest) is in Hillsborough, NH. Its focus is applied practical research, demonstration forests, and education and outreach for a variety of audiences. A Workshop Series on Forest Measurements for Natural Resource Professionals was held in the fall of 2001. These proceedings were prepared as a supplement to the workshop. Papers submitted were not peer-reviewed or edited. They were compiled by Karen P. Bennett, Extension Specialist in Forest Resources and Ken Desmarais, Forester with the NH Division of Forests and Lands. Readers who did not attend the workshop are encouraged to contact authors directly for clarifications. Workshop attendees received additional supplemental materials. Sampling and Management for Down Coarse Woody Debris in New England: A Workshop- October 12, 2001 The What and Why of CWD– Mark Ducey, Assistant Professor, UNH Department of Natural Resources New Hampshire’s Logging Efficiency– Ken Desmarais, Forester/ Researcher, Fox State Forest The Regional Level: Characteristics of DDW in Maine, NH and VT– Linda Heath, -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

CVP-19: Procedures for the Checking of Critical Dimensions of The

OMR-CVP-19 PROCEDURES FOR THE CHECKING OF CRITICAL DIMENSIONS OF THE CONICAL MOLD AND TAMPER AND THE CALIBRATION OF PYCNOMETERS AASHTO T 84 A. PURPOSE These procedures are intended to provide instruction for the verification of critical dimensions of the conical mold and tamper. B. APPARATUS REQUIRED 1. Calibrated calipers readable to 0.001 inch (.025 mm) 2. Calibrated balance capable of weighing 500 grams and readable to 0.1 gram. 3. Straightedge or ruler. 4. Thermometer readable to 0.1 °F or 0.1 °C. C. PROCEDURE Conical Cone 1. Measure the inside diameter of the top of the conical cone to the nearest 0.001 inch (.025 mm) by taking two (2) readings 90° apart with calipers and record results. 2. Invert cone and repeat Step 1 and record. 3. Place cone on a flat glass plate. Measure and determine the height of the cone by using the calipers and a straightedge and record results. 4. Measure and record the thickness of the cone to the nearest 0.001inch (.025 mm) with calipers by taking two (2) readings 90° apart on the top and bottom of cone. Tamper 1. Measure diameter of face of tamper by taking two (2) readings 90° apart. 2. Weigh and record weight of tamper to nearest 0.1 gram. Pycnometers Volumetric Flask (500 cm) calibrated annually at 21.3 °C – 24.7 °C (70.4 °F – 76.4 °F) by the following procedure: 1. Volumetric flasks are weighed empty and recorded to the nearest 0.1 gram. 2. Volumetric flasks are filled with water to the mark at which it is calibrated. -

Methodology for Afforestation And

METHODOLOGY FOR THE QUANTIFICATION, MONITORING, REPORTING AND VERIFICATION OF GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS REDUCTIONS AND REMOVALS FROM AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION OF DEGRADED LAND VERSION 1.2 May 2017 METHODOLOGY FOR THE QUANTIFICATION, MONITORING, REPORTING AND VERIFICATION OF GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS REDUCTIONS AND REMOVALS FROM AFFORESTATION AND REFORESTATION OF DEGRADED LAND VERSION 1.2 May 2017 American Carbon Registry® WASHINGTON DC OFFICE c/o Winrock International 2451 Crystal Drive, Suite 700 Arlington, Virginia 22202 USA ph +1 703 302 6500 [email protected] americancarbonregistry.org ABOUT AMERICAN CARBON REGISTRY® (ACR) A leading carbon offset program founded in 1996 as the first private voluntary GHG registry in the world, ACR operates in the voluntary and regulated carbon markets. ACR has unparalleled experience in the development of environmentally rigorous, science-based offset methodolo- gies as well as operational experience in the oversight of offset project verification, registration, offset issuance and retirement reporting through its online registry system. © 2017 American Carbon Registry at Winrock International. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced, displayed, modified or distributed without express written permission of the American Carbon Registry. The sole permitted use of the publication is for the registration of projects on the American Carbon Registry. For requests to license the publication or any part thereof for a different use, write to the Washington DC address listed above. -

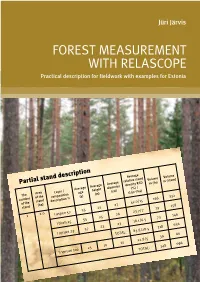

Forest Measurement with Relascope Practical Description for Fieldwork with Examples for Estonia

Jüri Järvis FOREST MEASUREMENT Practical descriptionWITH for fieldwork RELASCOPE with examples for Estonia Partial stand description Average The Area Layer / Average Average Average relative stand number of the Volume Volume composition age height diameter density RSD of the stand m3/ha m3/stand description % (y) (m) (cm) (%) / stand (ha) G (m2/ha) 1 2.0 I aspen 52 55 25 27 42.0/15 166 332 I birch 25 55 25 26 23.7/7 79 158 I spruce 23 57 23 23 18.1/6.5 73 146 TOTAL: 83.8/28.5 318 636 II spruce 100 25 10 10 22.8/5 30 60 TOTAL: 348 696 The relascope and relascope measurement was invented Title of the original: Metsa relaskoopmõõtmine. Puistu rinnaspindala, täiuse ja mahu and introduced by Austrian forest scientist Walter Bitterlich määramine lihtrelaskoopi kasutades. (Bitterlich 1947, 1948). The method is widely used because II täiendatud trükk (2010). it is simple, handy and quick. However, the method is less accurate when compared to cross-callipering forest Translation into English 2013; first printed 2006. measurement. It is used for the preliminary assessment of timber supply in a tree stand 1. © Jüri Järvis 2010; 2013. Simplified relascope is also called “simple relascope”, All rights reserved. “angle-counter”, “angle-gauge” or “angle-template”. So- called true relascope or mirror-relascope is a device that can automatically adjust its measured values according Consultants: Ahto Kangur, Allan Sims, Allar Padari, Andres Kiviste, Artur Nilson, to the slope of the ground (photo 1). Mart Vaus (Estonian University of Life Sciences, Institute of Forestry and Rural Engineering, Electronic relascope can be used instead of traditional Photo 1. -

Marking Centres, Squares and Hexagons

4 Marking centres, WORKSHOP squares and hexagons by GEOMETER ERE ARE THREE methods em- This is calculated from the diameter ployed for the essential work of the shaft’and its radius R. For of finding the centres of a square, R is multiplied by 0.707, for H a hexagon by 0.866. shafts or discs without setting them This dimension H is obtained on up in a lathe; 1, by the centre head an engineer’s steel rule with dividers. of a combination square; 2, by Then one leg of the dividers is placed jenny calipers-also called odd-leg in the shaft centre, and highest and or hermaphrodite calipers and 3, lowest positions marked-to one or by surface gauge and vee blocks on other of which the surface gauge a surface plate. pointer is adjusted. The first two are hand methods In marking, a line is carried across while the third is a shop or toolroom the end of the shaft and along the method. The use of a bell centre side(s) as required. Then the shaft is punch (a metal cone with a punch in unclamped, and for a square turned the centre, placed on the shaft and through 90 deg., as checked by the struck with a hammer), which is a engineer’s square, reclamped, and fourth way, is neither so universal nor another flat and side line scribed-this so accurate as the others. being done for all four. For a hexagon, the procedure is similar, but either the engineer’s square or the 60 deg. -

Dry Disc Brake Calipers

MAINTENANCE MANUAL DRY DISC BRAKE CALIPERS MANUFACTURED BY 2300 OREGON ST., SHERWOOD 97140, OR U.S.A. PHONE: 503.625.2560 • FAX: 503.625.7980 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: http://www.alliedsystems.com 80-767 3/2/2021 Contents pg. i Asbestos and Non-Asbestos Fibers 1 Section 1: Exploded View 2 Section 2: Introduction Description Hydraulic Fluid Identification 3 Section 3: Disassembly Manually Release the Brakes Releasing a Brake with Caging Studs and Nuts Releasing a Brake without Caging Studs and Nuts Remove the Caliper Disassemble the Caliper 5 Section 4: Prepare Parts for Assembly Cleaning Corrosion Protection 6 Section 5: Assembly Assemble the Caliper Prepare to Install the Linings Install the Linings 7 Install the Pistons, Linings and Springs Install the Caliper Bleeding the Brakes 8 Full Hydraulic Systems Air/Hydraulic or Mechanical Actuator Systems 9 Section 6: Adjust the Brakes Adjust the Brakes Adjusting a Brake with Caging Studs and Nuts Adjusting a Brake without Caging Studs and Nuts 10 Test the Caliper Adjusting the Caliper Off the Vehicle Adjusting the Caliper on the Vehicle 12 Section 7: Inspection Inspection Periodic On-Vehicle Inspections Inspect the Linings Inspect the Caliper for Leaks Inspect the Disc 13 Inspect Caliper Parts 14 Section 8: Diagnostics Troubleshooting 15 Section 9: Specifications Torque Specifications Wear Dimensions Total Lining-to-Disc Clearance Hydraulic Fluid Asbestos and Non-Asbestos Fibers Figure 0.1 ASBESTOS FIBERS WARNING NON-ASBESTOS FIBERS WARNING The following procedures for servicing brakes are recommended to reduce exposure to The following procedures for servicing brakes are recommended to reduce exposure to asbestos fiber dust, a cancer and lung disease hazard.