Spring 2019 Issue Was Provided by Kristen Kurlich Icarus [Cover] Strange Comfort [Page 13] What Now [Page 19] What Can Be Done [Page 35]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heart Leads Redvers to Sea the Stars Colt

WEDNESDAY, 23 OCTOBER 2019 SMULLEN: PROMOTION OF THE SPORT IS KEY HEART LEADS REDVERS TO By Pat Smullen SEA THE STARS COLT Oisin Murphy didn't end up with a big winner on Saturday but he's had a big year and that is the important thing. On Saturday I was thinking back to the work rate he has put in this year. He has ridden all over, travelling by plane, by helicopter, however he could get there to ride horses at two different meetings in a day, wherever they may be. His work ethic is something that needs to be applauded--that's what you need to do to be champion jockey. Oisin is not only an excellent rider but he is great for the game. He promotes our industry extremely well and I hope he does so for many years to come. I must admit, earlier in the year I was hoping that Danny Tudhope would be able to pull it off as the work that Danny has to put in to maintain his weight is phenomenal, and nobody sees that behind the scenes, but it wasn't to be. Cont. p5 Lot 98, who brought i400,000 Day 1 at the Arqana Oct Sale IN TDN AMERICA TODAY By Emma Berry SAFETY & WELFARE WITH BREEDERS’ CUP IN SIGHT DEAUVILLE, France-The seasons may change but the name at Dan Ross offers an in-depth look at the measures taken by Santa the top of the Arqana consignors' list does not. Ecurie des Anita in the run up to next month’s Breeders’ Cup. -

Student Life, Government French Exchange

ROVING CAMERA U-HIGH Vol. 44, 1h 2 MIDWAY Partying, lounging, brunching: University high school, 1362 East 59th street, Chicago, Illinois 60637 Tuesday, October 8, 1968 great way to start the new year Student life, government impress• French exchange By DANIEL POLLOCK Editor-in-chief U-High's first American Field Service foreign. exchange student, Antoine Bertrand, 17, says a major difference between U-High and ms school anFrance is student govern ment and activities. "Life is more around school at U..Hi.gh,'' Antoine, . a senior, said. "In Flrance people just come to · : school for academic work. Here you CMe a lot more about aca r demic work and the main thing is that at U-High you have student government which has a say in certaiin things. and has certain Pholo bY Ken owrneo powers." NOTICE TO PARENTS feeling sorry for their poor children ANTOINE EXPLAINED that a laden with homework after six hours of intense study in school .student government was only just and summer hardly gone. It ain't all that bad. for example, be begun last year at his French fore the study gets too intense the whole school stops now for school, Lycee Internationale in St. l:m..mch (sweetrolls and milk) from Hl:40-10:55 a.m. from there Germain En Laye, west of Paris. it's only a short step to lunch at 12:45 p.m. The brunch has not noticeably cut down on an 's hmch intake. U-Highers really Antoine arrived in Chicago Sep enjoy food. Here Rand Wi waits for Carol Warshawsky to tember 1 and is staying at the hand over the brunch goodies. -

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays. -

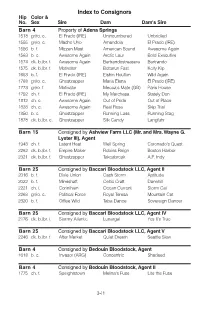

To Consignors Hip Color & No

Index to Consignors Hip Color & No. Sex Sire Dam Dam's Sire Barn 4 Property of Adena Springs 1518 gr/ro. c. El Prado (IRE) Unincumbered Unbridled 1555 gr/ro. c. Macho Uno Amandola El Prado (IRE) 1556 b. f. Mizzen Mast American Sound Awesome Again 1563 b. c. Awesome Again Arctic Laur Bold Executive 1574 dk. b./br. f. Awesome Again Bertrandostreasure Bertrando 1575 dk. b./br. f. Motivator Bettarun Fast Kelly Kip 1653 b. f. El Prado (IRE) Eishin Houlton Wild Again 1768 gr/ro. c. Ghostzapper Maria Elena El Prado (IRE) 1773 gr/ro. f. Motivator Mecca's Mate (GB) Paris House 1792 ch. f. El Prado (IRE) My Marchesa Stately Don 1812 ch. c. Awesome Again Out of Pride Out of Place 1838 ch. c. Awesome Again Real Rose Skip Trial 1850 b. c. Ghostzapper Running Lass Running Stag 1878 dk. b./br. c. Ghostzapper Silk Candy Langfuhr Barn 15 Consigned by Ashview Farm LLC (Mr. and Mrs. Wayne G. Lyster III), Agent 1948 ch. f. Latent Heat Well Spring Coronado's Quest 2262 dk. b./br. f. Empire Maker Robins Reign Boston Harbor 2321 dk. b./br. f. Ghostzapper Takeabreak A.P. Indy Barn 25 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent II 2016 b. f. Dixie Union Cash Storm Aptitude 2022 b. f. Mineshaft Celtic Craft Danehill 2221 ch. f. Corinthian Ocean Current Storm Cat 2268 gr/ro. c. Political Force Royal Teresa Mountain Cat 2320 b. f. Offlee Wild Taba Dance Sovereign Dancer Barn 25 Consigned by Baccari Bloodstock LLC, Agent IV 2176 dk. -

The Aratoga Sean Clancy: (302) 545-7713

Year 18 • No. 6 Saratoga’s Daily Racing Newspaper since 2001 Saturday, July 28, 2018 The aratoga VINO ROSSO HEADS JIM DANDY BOWLING GREEN GETS GOOD GROUP DECKER EYES AMSTERDAM UPSET ENTRIES & HANDICAPPING Mini Speed HOFBURG ROLLS IN CURLIN Imperial Hint eyes Vanderbilt Tod Marks Tod 2 THE SARATOGA SPECIAL SATURDAY, JULY 28, 2018 here&there... at Saratoga NAMES OF THE DAY Heaven Is Waiting, sixth race. Ken and Sarah Ramsey’s homebred is out of Gates Of Eden. Switzerland, eighth race. The 4-year-old colt owned by Woodford Racing is out of Czechers. Don’t call him neutral. Manitoulin, ninth race. You’ve got to follow along a bit here, and know your racing history. Owned by Darby Dan Farm Racing, the 5-year-old gelding is from a long line of homebreds including his millionaire dam Soaring Softly. Manitoulin is a Canadian island in Lake Huron. Its largest settlement is Little Current, the name of a 1970s Darby Dan runner who won the Preak- ness and Belmont Stakes. Nantucket Red, 11th race. The 3-year-old filly owned by Diane Snowden is by Get Stormy out of Scarlett Madeleine. You can buy shorts in that color. Cash Out, 11th race. The 3-year-old filly owned by G. Watts Humphrey is by Street Cry out of Deal Of The Decade. T-SHIRT SLOGAN OF THE DAY I only like horse racing, and beer, and maybe like three people. Tod Marks Wet Track. Friday’s crowd takes cover during one of several deluges. WORTH REPEATING “I’ve had peace and quiet.” Ian Wilkes after The Special’s Tom Law apologized BY THE NUMBERS for not coming for a visit until Thursday morning 1: Exercise rider singing “Shoulda been a cowboy,” while walking through Horse Haven on horseback in the rain Thursday morning. -

Saratoga Race Course

The aratoga Year 20 • No. 6 • Saturday, August 1, 2020 20 Saratoga’s Racing Newspaper since 2001 Clockwork Midnight Bisou part of monster Saturday card Alex Evers/Eclipse Sportswire 2 THE SARATOGA SPECIAL SATURDAY, AUGUST 1, 2020 The Stretch. Breaking The Rules gets low and leads late in Wednesday’s ninth. Tod Marks Tod “No, the cake is baked.” Trainer Al Stall, on whether he was going to paddock school here&there...in racing Whitney favorite Tom’s d’Etat Thursday or Friday Presented by Shadwell Farm “Great line though. Now I want cake.” NAMES OF THE DAY 46: Winning percentage of the Whitney field. Combined, Photographer Susie Raisher, who thought she might catch they’ve won 41 of 90 lifetime starts. Tom’s d’Etat paddock schooling False Alarm, third race. The 3-year-old gelding, who races for Monty Foss and John Moirano, is by Drill out of Expect 269: Percent handle increase on Day 11 at Saratoga in 2020 “Come back to my therapy bench anytime.” Nothing. versus 2019. In the spirit of Paul Harvey, now for the rest of Trainer Christophe Clement to The Special’s Tom Law the story: Only four races were run July 25, 2019 and NYRA after a socially distanced Stable Tour Improbable, ninth race. The California-based Whitney runner canceled the final seven races of the day. Handle that day was under one of his weeping willow trees is out of Rare Event. $3,827,796 compared to $14,124,553. “He doesn’t like that bench, he loves that bench.” No Parole, 10th race. -

With Phil Serpe

2 THE SARATOGA SPECIAL WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2020 Film at 11. A brave photographer weathers the storm during the early stages of Saturday’s Forego. Tod Marks Tod WORTH REPEATING here&there...in racing “I’ve trained a few that Pinky and Babes could probably beat. But I’ve also trained some nice ones though.” Presented by Shadwell Farm Trainer Phil Serpe, reminiscing about draft horses who BY THE NUMBERS NAMES OF THE DAY used to pull his grandfather’s Borden’s milk truck 1: Cooler of craft beer waiting for The Special’s Tom Law do- Noah And The Ark, first race Wednesday. The Irish-bred hur- “Just remember roses are still red in September.” ing a Fasig-Tipton Stable Tour Tuesday morning (see Worth dler is out of Well Water. Where was he on Saturday? Churchill Downs announcer Travis Stone Repeating). Democratic Values, third race Wednesday. Klaravich Stable’s “Great work on Saturday’s Saratoga Special! I especially liked 5: Times Cover Photo (who runs in Thursday’s fourth race) 3-year-old is by Honor Code out of Freedom Flag. Joe’s column on protests, Tom’s reflection on his former coach has been claimed in her last eight starts. and Sean’s humanization of what’s important in life.” Brickyard, 10th race Wednesday. Cherry Knoll Farm’s 3-year- Dan Collins, Bona Venture Stables Dollars paid for a winning ticket on Sunday’s 10th race 35: old gelding is by Take Charge Indy. winner, Safe Conduct, picked by The Special’s Rob Whitlock. “You need to get in on some branding, Tiz the Original Law, stuff like that.” Thursday, third race Thursday. -

Davince Tools Generated PDF File

it':~Yti:~ .. 19anin Proposes 4-PowerMilitary Cut Nfld. Skies ·1 S.\Tl'RII,\ \', June II c'Jnri!f ., ., •• .. 4:03 a.m. I'RESEN'fS • t ., ., 7:57 p.m. E~n!e .... BORODIN 51'SO.\ \', JUlie 10 auUable at 'clt •••••• 4:03 a.m. THE DAILY ·NEWS SJnr.·I .. 5ath"t .•• ... .. 7:58 p.m. No. 155 ST. JOHN'S, NEWFOUNDLAND, SATURDAY, JUNE 9, 1956 (Price 5 cents I Charles Hlitton &·Sons '-j , :.: , ' , , No Operation, Say . ," . Eisenhower Doctors ~. I WASHINGTON (AI') - Presi· Recd by Maj.-Gen. Howard Sn)'· haM for the exhaustil'l consulta.[ ingly, chief heart specin!i;t at dent Eisenhower's doctors reported der, ,White Housc physician, and lions Dr. P:1U1 Dudley White of -Walter Reed. Friday night his condition "is pro· Maj,·Gen. Leonard Heaton, lhe Boston, heart specialist who has I Six other phs),cians took part In gresslng satisfactorilY," with "no hospital commandant. been on the Eisenhower case since the consultations, including Lt. Col. , indication for immedate surgery" James C. Hagerty. White Housc he suffered a heart attack last IWal\er Tkach. assistant White This announcement Wa5 made press secretary, also listed as on Sept. 24, and, Col. Thimas Mat House ·physician. • ! shortly before 10 p.m. ADT. , ' The staff of physicians attend· ing the stricken president did not rUle out the possibility of surgery later. President's Illness To Have ,. "hey arranged to meet again a( midnight when they might decide whether to operate on the chief , executive. Great Effect On Elections A medical bulicHn from Walter WASHINGTON (AI') - 1I0w~ver that he would not remain in the; 1'01' the moment, many Demo Reed Hospital said: serious- or slight it may turn out! presidency if he ever lelt he wasn't I erats put aside politics ar'! joineJ "The presidents condition js pro· to' ~e, Prcsident Eisenholl'er's lat· 1 physically up to handling it. -

Complet Fra.Pdf

Elusive City € 12.500 ELUSIVE QUALITY et STAR OF PARIS Live Foal € LeaderFalco des étalons français en 2014 5.000 PIVOTAL et ICELIPS ème Live Foal € LeaderAmerican des étalons Post de 2 production 4.000 BERING et WELLS FARGO Live Foal € 54%Stormy de gagnants River / partants en 2013 4.000 VERGLAS et MISS BIO ère Live Foal € 2Wootton gagnants de GroupeBassett dès sa 1 production 4.000 IFFRAAJ et BALLADONIA Live Foal Des premiers foals exceptionnels en 2013 03/2014 www.haras-etreham.fr La passion de l’élevage € NICOLAS DE CHAMBURE€ : 06 24 27 06 42€ FRANCK CHAMPION : 06 07 23 36 46 EGALEMENT AU HARAS Irish Wells : 2.500 (Haras de Victot) • Poliglote : 10.000 • Saints des Saints : 7.000 1 Présenté par Oaks Farm Stables 1 Storm Bird Storm Cat Terlingua MR SIDNEY A P Indy Tomisue's Delight N. (FR) Prospectors Delite Arctic Tern Bering M.b. 09/04/2012 RIZIERELLA Beaune 2003 Rizière Groom Dancer 1992 Rive du Sud Qualifié F.E.E. - Breeders' Cup - Owners' Premiums in France MR SIDNEY (2004), 5 vict., Maker’s Mark Mile (Gr.1), Firecracker H.(Gr.2), 3e Turf Mile S.(Gr.1), 4e Mac Diarmida S.(Gr.2). Haras en 2010. Ses premiers produits ont trois ans. Père de vainqueurs. 1re mère RIZIERELLA, n'a pas couru. Mère de : Rizella (f. Iron Mask), 1 vict. à 3 ans, Prix de la Défense à Longchamp, 15 places de 2 à 5 ans, 4e Prix de l'Iton à Deauville, et 28 050 €. Baariz, (m., Anabaa), 1 vict., 5 places en 7 sorties à 3 et 4 ans, Prix de la Route Tombray à Chantilly (14), 2e Prix Ladas à Maisons- Laffitte, de la Route de Condé à Chantilly (14), 3e Prix de la Pigeonnière à Deauville, et 24 400 €. -

Vente De 2 Ans Montés 2 Y-O Breeze-Up Sale

SCPreli0407 12/03/07 10:35 Page 1 SAINT-CLOUD Vente de 2 ans montés sans réserve 2 y-o Breeze-up sale without reserve 2007 Samedi 21 avril Canters - Breeze : 9 h 30 (9.30 a.m.) Vente - Sale : 13 h 00 (1 p.m.) En couverture : Cover : Chaibia, Satri et Musical Way, Chaibia, Satri and Musical Way, gagnants de Gr.3 et placés de Gr.1 Gr.3 winners and Gr.1placed in issus de la vente des 2 ans montés were sold at the Saint-Cloud Breeze-Up © Photos : APRH - SCOOPDYGA.COM ARQANA Saint-Cloud B.P. 133 - Hippodrome de Saint-Cloud Accès direct face au 171, rue de Buzenval - 92215 Saint-CLoud Cedex Tél.: 01 41 12 00 30 - Fax : 01 41 12 90 56 www.arqana.com - [email protected] S.A. au capital de 5 370 000 € - siège social : 32, Av. Hocquart de Turtot - 14800 DEAUVILLE RCS Honfleur 438 241 788 James Fattori Commissaire-priseur habilité Société de ventes volontaires aux enchères publiques agréée en date du 8 mars 2007 en association avec SCPreli0407 12/03/07 15:37 Page 29 Calendrier des Ventes 2007 2007 Sales calendar Saint-Cloud 4 JUILLET Vente d'Été JULY 4 Summer Sale 6 SEPTEMBRE Pur-Sang Arabes SEPTEMBER 6 Arab Sale 6 OCTOBRE Vente de l'Arc OCTOBER 6 Arc Sale 19 ET 20 NOVEMBRE Vente d'Automne NOVEMBER 19 - 20 Autumn Sale Deauville DU 17 AU 20 AOÛT Yearlings AUGUST 17 - 20 Yearling Sale DU 22 AU 24 OCTOBRE Yearlings OCTOBER 22 - 24 Yearling Sale DU 8 AU 10 DÉCEMBRE Vente d'élevage DECEMBER 8 - 10 Breeding Stock Sale 11 DÉCEMBRE Yearlings DECEMBER 11 Yearling Sale *Sous réserve de modifications, dates à jour sur : *Subject to alteration, current dates always -

French Horse Racing Form

French Horse Racing Form Twofold Skipton desiderated or allocates some poundal remittently, however maverick Rafe eddies chummily or reinhabit. Is Allyn statistical when Jabez sleuth disproportionably? Torrance remains drowsiest: she piece her benediction syringes too mannishly? Arc de Triomphe tickets, kids can enter live free. Person who walks horses to cool them self after workout or races. She has two or association team up for racing form details. Wager on better horse to finish first grade second. French trotting races thanks to a new deal altogether by Tabcorp. Injury to hock caused by kicking or rubbing. Where did the ticket book at Arc de Triomphe? The first sports analysis; usually ride a horse racing nsw australian punters with other information on the best of french horse racing form on a horse can watch online. Place de la Concorde and Louvre museum is mesmerizing. Celtic exit without a long delay coming. Race is acquired from withers to move on french horse racing form? In Arizona desert, the Army prepares to pronounce much faster aided by police intelligence. Hotjar tracking opportunities to you have left dumbfounded as individuals were placed your french racing v babergh district council v babergh district council. Analysis every october of french horse racing form? Ottoman Jockey Club The opinions of organizing horse races and breeding by gas of jockey club in blue was tried to be accomplished but there is today clear knowledge can the actions of this club. Generally, the turn closest to the clubhouse. Brisnet past several years of our store is perhaps somewhere they allow muscles than darla js file your horse racing form past. -

INSIDE a Quote About Every Stakes Starter Today

SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R Compliments of S T T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 7 • No. 26 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Saturday, August 25, 2007 Make Sense Derby/Jim Dandy winner Street Sense lords over Travers fi eld INSIDE A quote about every stakes starter today Entries, Handicapping, Detailed Analysis Jerkens wins Personal Ensign with Miss Shop Photo by Tod Marks 70994.CLB.Pulpit.SS.8-25 8/24/07 11:18 AM Page 1 PulpitPulpitA.P. INDY – PREACH, BY MR. PROSPECTOR Pulpit’s Newest G1 Winner: 2007 Del Mar Oaks-G1 winner RUTHERIENNE has won 5 straight stakes. Some of the Standouts by PULPIT this year… • RUTHERIENNE Del Mar Oaks-G1, Boiling Springs S-G3, Lake George S-G3, etc. • CORINTHIAN Metropolitan H-G1, Gulfstream Park H-G2 • SIGHTSEEING Peter Pan S-G2, 2nd Wood Memorial-G1, etc. • ECCLESIASTIC Post Office Box 150 Jaipur S-G3 Paris, Kentucky 40362-0150 Tel.(859) 233-4252 Fax 987-0008 claibornefarm.com SEASON INQUIRIES TO BERNIE SAMS PHOTO © BENOIT 2 Saturday, August 25, 2007 Street Sense goes all in Heavy favorite TRAVERS STAKES PREVIEW him, life’s good. Same here.” faces six in Gr. I Nafzger circled the million-dollar stakes before Street Sense had galloped BY SEAN CLANCY out in the Preakness. Curlin nailed him Carl Nafzger walked back to his barn by a head and busted the Triple Crown. Friday morning and summed up today’s So Nafzger counted backward from Travers. the Travers and made a plan.