Rabinder Nath Tagore : Gitanjali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist a Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd

2018 Heritage Vol.-V Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist A Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd. Associate Professor, Dept. of Political Science, Bethune College, Kolkata-6 Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore, although basically a poet, had a multifaceted personality. Among his various activities his sincerity as a social thinker and activist attract our attention. But this area is till now comparatively unexplored. Many scholars in this area have tried to study Tagore as a social thinker. But so far the findings are scattered and on the whole there is no comprehensive analysis in the strict sense of the term. Hence it is necessary to collect the different findings and to integrate and arrange them within a theoretical framework. This article is an attempt to make a review of literature of the existing books and to prepare a short but sharp bibliography to introduce the area. Key words: Rabindranath Tagore, society, social, political, history, education, Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) was a prolific writer, a successful music composer, a painter, an actor, a drama director and what not. Besides these talents, he was also a social activist and contributed a lot to Indian social and political thought, although this area has not been very much explored till now. Tagore was emphatic upon society building. So he tried to develop all the component elements which were essential for developing the Indian society. He studied the history of India to follow the trend of its evolution. Next he prepared his programme of action – rural reconstruction and spread of education. -

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

Sri Aurobindo: a Postmodern Sublime Poet Dr

Sri Aurobindo: A Postmodern Sublime Poet Dr. Atal Kumar Among all the leading poets of the early twentieth century Indian English poets Sri Aurobindo is vibrant with the contemporary literary ethos–modernism vis-a-vis postmodernism. His modernism was not haunted by what T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound found during the First World War rather pressed by his inner urge of Sublime. Sri Aurobindo's Muse was drenched in the showers of Sublime. He had been a great Indian religious, philosophical and social thinker as well as postmodern sublime poet. The great spiritual master was born on 15 August 1872 in an aristocratic and anglicised family in Calcutta. Sri Krishnandan Ghose, his father, was among them who first went to England for his medical education and returned with anglophilic blood in his veins. Certainly, the early life of that mystic poet was moulded under the parasol of his father's anglicised habits, ideas and ideals. His father's anglophilic disposition induced him to keep his children away from the Indian ways of life. On the contrary Sri Aurobindo's mother Swarnlata Devi belonged to the clan of great Indian Renaissance man of the nineteenth century, Rishi Rajnarayan Bose. She was the adviser of the new composite culture of Indian soil. Dr. Krishnandan Ghose's inner temperament forced him to nurture him in English atmosphere and not from native ways and native language. As a result of that Sri Aurobindo along with his elder brothers Sri Manmohan Ghose and Sri Benoy Bhushan Ghose were admitted to Loreto Convent School at Darjeeling. -

2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected]

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected] In-charge of English Department, Ideal College of Arts & Sciences (A), Kakinada It may not be hyperbolic to As an educationist, reformer say that there may not be such a great politician, and follower of Brahmo Samaj, man as Tagore. Just two points are worth he assimilated the best in the oriental enough to mention here. He was the tradition. fought against the bigotry and author of our National Anthem . At least inertia of conventional Hinduism. He 40 crore Indians stand up to respect the relinquished his knight hood. National Anthem, when it is sung or As a painter, Tagore struck the played on music. He was the author of golden mean between traditionalism and the National Anthem of Bangladesh also. impressionism. “Genuinely original, There also a good number of people genuinely native”. Again, as a musician respect their National Anthem by he established a pleasing synthesis standing in attention. What else would between classical and light music, the dead soul requires to be joyous, if at Rabidra Sangeet will enjoy eternal youth. all we have belief on soul. As a dramatist, he started with verse- Above all he was the first Asian plays and ended with dance drama. He to receive the Noble Prize for English was also an actor. literature in 1913. The writing of Tagore began his poetic career at Gitanjali, written in a foreign language the age of eight and continued it until the was preferred to the writings of even the last day of his eventful life. -

PAPER VI UNIT I Non-Fictional Prose—General

PAPER VI UNIT I Non-fictional Prose—General Introduction, Joseph Addison’s The Spectator Papers: The Uses of the Spectator, The Spectator’s Account of Himself, Of the Spectator 1.1. Introduction: Eighteenth Century English Prose The eighteenth century was a great period for English prose, though not for English poetry. Matthew Arnold called it an "age of prose and reason," implying thereby that no good poetry was written in this century, and that, prose dominated the literary realm. Much of the poetry of the age is prosaic, if not altogether prose-rhymed prose. Verse was used by many poets of the age for purposes which could be realized, or realized better, through prose. Our view is that the eighteenth century was not altogether barren of real poetry. Even then, it is better known for the galaxy of brilliant prose writers that it threw up. In this century there was a remarkable proliferation of practical interests which could best be expressed in a new kind of prose-pliant and of a work a day kind capable of rising to every occasion. This prose was simple and modern, having nothing of the baroque or Ciceronian colour of the prose of the seventeenth-century writers like Milton and Sir Thomas Browne. Practicality and reason ruled supreme in prose and determined its style. It is really strange that in this period the language of prose was becoming simpler and more easily comprehensible, but, on the other hand, the language of poetry was being conventionalized into that artificial "poetic diction" which at the end of the century was so severely condemned by Wordsworth as "gaudy and inane phraseology." 1.2. -

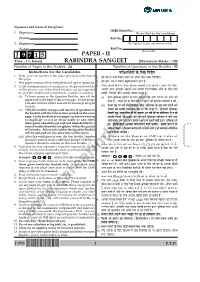

Copy of OMR Sheet on Conclusion of Examination

Signature and Name of Invigilator OMR Sheet No. : .......................................................... 1. (Signature) (To be filled by the Candidate) (Name) Roll No. 2. (Signature) (In figures as per admission card) (Name) Roll No. (In words) J 9715 PAPER - II Time : 1¼ hours] RABINDRA SANGEET [Maximum Marks : 100 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 24 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 50 Instructions for the Candidates ÂÚUèÿææçÍüØô¢ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÙÎðüàæ 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. §â ÂëDU ·ð¤ ª¤ÂÚU çÙØÌ SÍæÙ ÂÚU ¥ÂÙæ ÚUôÜU ÙÕÚU çÜç¹°Ð this page. 2. This paper consists of fifty multiple-choice type of questions. 2. §â ÂýàÙ-Âæ ×𢠿æâ Õãéçß·¤ËÂèØ ÂýàÙ ãñ´Ð 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet 3. ÂÚUèÿææ ÂýæÚUÖ ãôÙð ÂÚU, ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¥æ·¤ô Îð Îè ÁæØð»èÐ ÂãÜðU ÂUæ¡¿ ç×ÙÅU will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested ¥æ·¤ô ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ÌÍæ ©â·¤è çÙÙçÜç¹Ì Áæ¡¿ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÎØð to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : ÁæØð¢»ð, çÁâ·¤è Áæ¡¿ ¥æ·¤ô ¥ßàØ ·¤ÚUÙè ãñ Ñ (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the (i) ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ·ð¤ çÜ° ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ÂÚU Ü»è ·¤æ»Á ·¤è âèÜ ·¤æð paper seal on the edge of this cover page. Do not accept ȤæǸ Üð¢UÐ ¹éÜè ãé§ü Øæ çÕÙæ SÅUè·¤ÚU-âèÜU ·¤è ÂéçSÌ·¤æ Sßè·¤æÚU Ù ·¤Úð¢UÐ a booklet without sticker-seal and do not accept an open booklet. -

Indian Angles

Introduction The Asiatic Society, Kolkata. A toxic blend of coal dust and diesel exhaust streaks the façade with grime. The concrete of the new wing, once a soft yellow, now is dimmed. Mold, ever the enemy, creeps from around drainpipes. Inside, an old mahogany stair- case ascends past dusty paintings. The eighteenth-century fathers of the society line the stairs, their white linen and their pale skin yellow with age. I have come to sue for admission, bearing letters with university and government seals, hoping that official papers of one bureaucracy will be found acceptable by an- other. I am a little worried, as one must be about any bureaucratic encounter. But the person at the desk in reader services is polite, even friendly. Once he has enquired about my project, he becomes enthusiastic. “Ah, English language poetry,” he says. “Coleridge. ‘Oh Lady we receive but what we give . and in our lives alone doth nature live.’” And I, “Ours her wedding garment, ours her shroud.” And he, “In Xanadu did Kublai Khan a stately pleasure dome decree.” “Where Alf the sacred river ran,” I say. And we finish together, “down to the sunless sea.” I get my reader’s pass. But despite the clerk’s enthusiasm, the Asiatic Society was designed for a different project than mine. The catalog yields plentiful poems—in manuscript, on paper and on palm leaves, in printed editions of classical works, in Sanskrit and Persian, Bangla and Oriya—but no unread volumes of English language Indian poetry. In one sense, though, I have already found what I need: that appreciation of English poetry I have encountered everywhere, among strangers, friends, and col- leagues who studied in Indian English-medium schools. -

Background to Indian English Poetry

Chapter : 1 Background to Indian English Poetry 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2. History of Indian English Poetry 1.2.1 Poetry of first phase 1.2.2 Poetry of second phase 1.2.3 Post independence poetry 1.3. Major Indian English Poets 1.3.1 Pre- independence poets 1.3.2 Post - Independence Poets 1.4. Major themes dealt in Indian English Poetry 1.4.1 Pre-independence Poetry Themes 1.4.2 Post - Independence Poetry Themes 1.5 Conclusion 1.6 Summary - Answers to Check Your Progress - Field Work 1.0 Objectives Friends, this paper deals with Indian English Literature and we are going to begin with Indian English verses. After studying this chapter you will be able to - · Elaborate the literary background of the Indian English Poetry · Take a review of the growth and development of Indian English verses · Describe different phases and the influence of the contemporary social and political situations. · Narrate recurrent themes in Indian English poetry. Background to Indian English Poetry / 1 1.1 Introduction Friends, this chapter will introduce you to the history of Indian English verses. It will provide you with information of the growth of Indian English verses and its socio-cultural background. What are the various themes in Indian English poetry? Who are the major Indian English poets? This chapter is an answer to these questions with a thorough background to Indian English verses which will help you to get better knowledge of the various trends in Indian English poetry. 1.2 History of Indian English Poetry Poetry is the expression of human life from times eternal. -

Dus Mahavidyas

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Rabindranath Tagore – A Beacon of Light Copyright © 2011, DollsofIndia Jeebono Jokhon Shukaey Jaey When the heart is hard and parched up Korunadharaey Esho come upon me with a shower of mercy. Shokolo Madhuri Lukaey Jaey When grace is lost from life Geetoshudharoshe Esho come with a burst of song. Kormo Jokhon Probolo Aakar When tumultuous work raises its din Goroji Uthiya Dhake Chari Dhar on all sides shutting me out from beyond, Hridoyprante, Hey Jibononath come to me, my lord of silence Shanto Chorone Esho with thy peace and rest. Aaponare Jobe Koriya Kripon When my beggarly heart sits crouched Kone Pore Thake Deenohino Mon shut up in a corner, Duraar Khuliya, Hey Udaaro Nath break open the door, my king Raajoshomarohe Esho and come with the ceremony of a king Bashona Jokhon Bipulo Dhulaey When desire blinds the mind Ondho Koriya Obodhe Bhulaey with delusion and dust Ohe Pobitro, Ohey Onidro O thou holy one, thou wakeful Rudro Aaloke Esho come with thy light and thy thunder - a poem from the collection - Transalated by Rabindranath Tagore "Gitanjali" Original writing of Rabindranath Tagore Courtesy Gitabitan.net This song was sung by Rabindranath Tagore for Mahatma Gandhi, on September 26, 1932, right after Gandhi broke his fast unto death, undertaken to force the colonial British Government to abjure its decision of separation of the lower castes as an electorate in India. Tagore was and will remain one of the greatest poets and philosophers the world has ever seen. His contribution to Indian literature, music, arts and drama endeared him not only to Bengalis but to Indians and the world at large. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by