PAPER VI UNIT I Non-Fictional Prose—General

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delightful Visibility and Its Limits. Joseph Addison on “The

Delightful Visibility and its Limits. Joseph Addison on “The Pleasures of the Imagination” It is undoubtedly his close connection to Cartesianism1 which leads the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche at the end of the 17th century to pay little attention to the relevance of the imagination for the realm of the visible. His programme of rationalism with its ambition to marginalize the human faculty of creating images by assigning it to a worthless sense perception renders it almost impossible to recognize the constitutive function of this faculty for visuality in general. A few decades later, however, things change with the emergence of empiricism and the publication of John Locke’s Essay concerning Human Understanding, especially with regard to the differentiation between primary and secondary qualities.2 According to this distinction, qualities like colours, sounds and tastes are not part of the material object itself but constructed in the process of perception. In contrast to primary qualities like extension and figure, which belong directly to the material object, secondary qualities like colours, sounds and tastes emerge from the imagination, proving it to be an important part of perception in general. Concerning these particular notions, it was Locke who gave Joseph Addison the cue for his Essay on the Pleasures of the Imagination.3 As unmistakably announced in the title of his essay, Addison undertakes nothing less than a counter-programme to Malebranche’s devaluation of the imagination, turning towards the delights affiliated with this faculty and at the same time attempting to establish a theoretical approach. Unlike other discourses on the imagination4, he does not attempt to defend or justify a ‚lesser’ human faculty. -

Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key”

“Down the Winding Stair”: Victorian Popular Science and Deep Time in “The Golden Key” Geoffrey Reiter t is sometimes tempting to call George MacDonald’s fantasies “timeless”I and leave it at that. Such is certainly the case with MacDonald’s mystical fairy tale “The Golden Key.” Much of the criticism pertaining to this work has focused on its more “timeless” elements, such as its intrinsic literary quality or its philosophical and theological underpinnings. And these elements are not only important, they truly are the most fundamental elements needed for a full understanding of “The Golden Key.” But it is also important to remember that MacDonald did not write in a vacuum, that he was in fact interested in and engaged with many of the pressing issues of his day. At heart always a preacher, MacDonald could not help but interact with these issues, not only in his more openly didactic realistic novels, but even in his “timeless” fantasies. In the Victorian period, an era of discovery and exploration, the natural sciences were beginning to come into their own as distinct and valuable sources of knowledge. John Pridmore, examining MacDonald’s view of nature, suggests that MacDonald saw it as serving a function parallel to the fairy tale or fantastic story; it may be interpreted from the perspective of Christian theism, though such an interpretation is not necessary (7). Björn Sundmark similarly argues that in his works “MacDonald does not contradict science, nor does he press a theistic interpretation onto his readers” (13). David L. Neuhouser has concluded more assertively that while MacDonald was certainly no advocate of scientific pursuits for their own sake, he believed science could be of interest when examined under the aegis of a loving God (10). -

The Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment Free Download

THE DIVINE WITHIN: SELECTED WRITINGS ON ENLIGHTENMENT FREE DOWNLOAD Aldous Huxley,Huston Smith | 305 pages | 02 Jul 2013 | HARPER PERENNIAL | 9780062236814 | English | New York, United States The Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment (Paperback) Born into a French noble family in southern France, Montesquieu practiced law in adulthood and witnessed great political upheaval across Britain and France. Aldous Huxley mural. Animal testing Archival research Behavior epigenetics Case The Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment Content analysis Experiments Human subject research Interviews Neuroimaging Observation Psychophysics Qualitative research Quantitative research Self-report inventory Statistical surveys. By the decree of the angels, and by the command of the holy men, we excommunicate, expel, curse and damn Baruch de Espinoza, with the consent of God, Blessed be He, and with the consent of all the Holy Congregation, in front of these holy Scrolls with the six-hundred-and-thirteen precepts which are written therein, with the excommunication with which Joshua banned The Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment[57] with the curse with which Elisha cursed the boys [58] and with all the curses which are written in the Book of the Law. Huxley consistently examined the spiritual basis of both the individual and human society, always seeking to reach an authentic and The Divine Within: Selected Writings on Enlightenment defined experience of the divine. Spinoza's Heresy: Immortality and the Jewish Mind. And when I read about how he decided to end his life while tripping on LSD I thought that was really heroic. Miguel was a successful merchant and became a warden of the synagogue and of the Amsterdam Jewish school. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected]

International Journal of Academic Research ISSN: 2348-7666; Vol.3, Issue-7(4), July, 2016 Impact Factor: 3.656; Email: [email protected] In-charge of English Department, Ideal College of Arts & Sciences (A), Kakinada It may not be hyperbolic to As an educationist, reformer say that there may not be such a great politician, and follower of Brahmo Samaj, man as Tagore. Just two points are worth he assimilated the best in the oriental enough to mention here. He was the tradition. fought against the bigotry and author of our National Anthem . At least inertia of conventional Hinduism. He 40 crore Indians stand up to respect the relinquished his knight hood. National Anthem, when it is sung or As a painter, Tagore struck the played on music. He was the author of golden mean between traditionalism and the National Anthem of Bangladesh also. impressionism. “Genuinely original, There also a good number of people genuinely native”. Again, as a musician respect their National Anthem by he established a pleasing synthesis standing in attention. What else would between classical and light music, the dead soul requires to be joyous, if at Rabidra Sangeet will enjoy eternal youth. all we have belief on soul. As a dramatist, he started with verse- Above all he was the first Asian plays and ended with dance drama. He to receive the Noble Prize for English was also an actor. literature in 1913. The writing of Tagore began his poetic career at Gitanjali, written in a foreign language the age of eight and continued it until the was preferred to the writings of even the last day of his eventful life. -

Tagore's Song Offerings: a Study on Beauty and Eternity

Everant.in/index.php/sshj Survey Report Social Science and Humanities Journal Tagore’s Song Offerings: A Study on Beauty and Eternity Dr. Tinni Dutta Lecturer, Department of Psychology , Asutosh College Kolkata , India. ABSTRACT Gitanjali written by Rabindranath Tagore (and the English translation of the Corresponding Author: Bengali poems in it, written in 1921) was awarded the Novel Prize in 1913. He Dr. Tinni Dutta called it Song Offerings. Some of the songs were taken from „Naivedya‟, „Kheya‟, „Gitimalya‟ and other selections of his poem. That is, the Supreme Being is complete only together with the soul of the devetee. He makes the mere mortal infinite and chooses to do so for His own sake, this could be just could be a faint echo of the AdvaitaPhilosophy.Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali express the distinctive method of philosophy…The poet is nothing more than a flute (merely a reed) which plays His timeless melodies . His heart overflows with happiness at His touch that is intangible Tagore‟s song in Gitanjali are analyzed in this ways - content analysis and dynamic analysis. Methodology of his present study were corroborated with earlier findings: Halder (1918), Basu (1988), Sanyal (1992) Dutta (2002).In conclusion it could be stated that Tagore‟s songs in Gitanjali are intermingled with beauty and eternity.A frequently used theme in Tagore‟s poetry, is repeated in the song,„Tumiaamaydekechhilechhutir‟„When the day of fulfillment came I knew nothing for I was absent –minded‟, He mourns the loss. This strain of thinking is found also in an exquisite poem written in old age. -

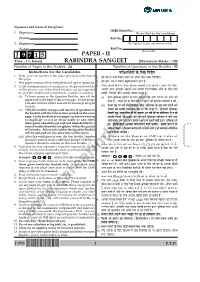

Copy of OMR Sheet on Conclusion of Examination

Signature and Name of Invigilator OMR Sheet No. : .......................................................... 1. (Signature) (To be filled by the Candidate) (Name) Roll No. 2. (Signature) (In figures as per admission card) (Name) Roll No. (In words) J 9715 PAPER - II Time : 1¼ hours] RABINDRA SANGEET [Maximum Marks : 100 Number of Pages in this Booklet : 24 Number of Questions in this Booklet : 50 Instructions for the Candidates ÂÚUèÿææçÍüØô¢ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÙÎðüàæ 1. Write your roll number in the space provided on the top of 1. §â ÂëDU ·ð¤ ª¤ÂÚU çÙØÌ SÍæÙ ÂÚU ¥ÂÙæ ÚUôÜU ÙÕÚU çÜç¹°Ð this page. 2. This paper consists of fifty multiple-choice type of questions. 2. §â ÂýàÙ-Âæ ×𢠿æâ Õãéçß·¤ËÂèØ ÂýàÙ ãñ´Ð 3. At the commencement of examination, the question booklet 3. ÂÚUèÿææ ÂýæÚUÖ ãôÙð ÂÚU, ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¥æ·¤ô Îð Îè ÁæØð»èÐ ÂãÜðU ÂUæ¡¿ ç×ÙÅU will be given to you. In the first 5 minutes, you are requested ¥æ·¤ô ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ÌÍæ ©â·¤è çÙÙçÜç¹Ì Áæ¡¿ ·ð¤ çÜ° çÎØð to open the booklet and compulsorily examine it as below : ÁæØð¢»ð, çÁâ·¤è Áæ¡¿ ¥æ·¤ô ¥ßàØ ·¤ÚUÙè ãñ Ñ (i) To have access to the Question Booklet, tear off the (i) ÂýàÙ-ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ¹ôÜÙð ·ð¤ çÜ° ÂéçSÌ·¤æ ÂÚU Ü»è ·¤æ»Á ·¤è âèÜ ·¤æð paper seal on the edge of this cover page. Do not accept ȤæǸ Üð¢UÐ ¹éÜè ãé§ü Øæ çÕÙæ SÅUè·¤ÚU-âèÜU ·¤è ÂéçSÌ·¤æ Sßè·¤æÚU Ù ·¤Úð¢UÐ a booklet without sticker-seal and do not accept an open booklet. -

![Rabindranath Tagore Passed Away - [August 7, 1941] This Day in History](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4064/rabindranath-tagore-passed-away-august-7-1941-this-day-in-history-554064.webp)

Rabindranath Tagore Passed Away - [August 7, 1941] This Day in History

Rabindranath Tagore Passed Away - [August 7, 1941] This Day in History Rabindranath Tagore was an important figure in the Indian freedom struggle and served an inspiration to many. In this article, you can read about his life and contributions to the IAS Exam. Rabindranath Tagore Biography Rabindranath Tagore, also called ‘Gurudev’ passed away on 7 August 1941 at Jorasanko, Calcutta in his ancestral home. He was 80. • Rabindranath Tagore was born on 7 May 1861 to an upper-class Bengali family in his ancestral home in Calcutta. • He became the most influential writer, poet and artist in Bengal and also India in the early 20th century • He was a polymath and his mastery spread over many arenas like art, literature, poetry, drama, music and learning. • He became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature when he won the award in 1913 for his translation of his own work in Bengali, Gitanjali. He was the first non-white person to win a Nobel Prize. • Tagore is said to have composed over 2000 songs and his songs and music are called ‘Rabindrasangeet’ with its own distinct lyrical and fluid style. • The national anthems of both India and Bangladesh were composed by Tagore. (India’s Jana Gana Mana and Bangladesh’s Amar Shonar Bangla.) • The Sri Lankan national anthem is also said to have been inspired by him. • Tagore had composed Amar Shonar Bangla in 1905 in the wake of the Bengal partition to foster a spirit of unity and patriotism among Bengalis. He also used the Raksha Bandhan festival to bring about a feeling of brotherhood among Bengal’s Hindus and Muslims during the partition of 1905. -

Masculinization of Tragedy in Joseph Addison's Cato and George Lillo's

Litera: Dil, Edebiyat ve Kültür Araştırmaları Dergisi Litera: Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Litera 2018; 28(2): 233-252 DOI: 10.26650/LITERA2018-0006 Research Article Masculinization of Tragedy in Joseph Addison’s Cato and George Lillo’s The London Merchant Joseph Addison’un Cato ve George Lillo’nun Londralı Tüccar Eserlerinde Tragedyanın Maskülenleşmesi Sinan GÜL1 ABSTRACT During the 18th century, the development of gender and sexuality in the modern Western world was under tremendous impact of visual and literary culture. Considering this, by examining Addison’s Cato. A Tragedy. By Mr. Addison. Without the Love Scenes (1764) (Latin version) and Lillo’s The London Merchant (1731), this article analyzes the masculine features of the characters of 18th-century tragedies in England and investigates the reasons behind the dismissal and belittlement of love scenes and feminine qualities in those tragedies. In comedies, women and their qualities were openly ridiculed, while in tragedies, masculine values and patriarchal rules were overtly protected. Depicting societal norms and ideals, Cato and The London Merchant portray the evolving notions of masculinity. Despite increasing female influence in political and social culture, love, often associated with feminine qualities, was belittled in domestic and public domains. In doing so, playwrights either entirely ignored the idea of using female characters in their plays, thus creating contextual errors of portraying husbands without wives or sons without mothers, or depicted women as the sources of passion that could potentially destroy society, men in particular. Therefore, the concept of love was neglected, undervalued, or dismissed, with playwrights rather offering patriotic or capitalist virtues to substitute the idea of love so that their plays would be deemed as appropriate for public appreciation. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe

Hasan Deniz · Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe Evolution Education Around the Globe [email protected] Hasan Deniz • Lisa A. Borgerding Editors Evolution Education Around the Globe 123 [email protected] Editors Hasan Deniz Lisa A. Borgerding College of Education College of Education, Health, University of Nevada Las Vegas and Human Services Las Vegas, NV Kent State University USA Kent, OH USA ISBN 978-3-319-90938-7 ISBN 978-3-319-90939-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90939-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018940410 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

1822 ESSAYS Charles Lamb

1822 ESSAYS Charles Lamb Lamb, Charles (1775-1834) - English essayist and critic well-known for the humorous and informal tone of his writing. His life was marked by tragedy and frustration; his sister Mary, whom he took lifelong care of, killed their parents in a fit of madness, and he himself spent time in a madhouse. Essays (1822) - A collection of essays written by Lamb under the pseudonym, “Elia,” including, among others, “On the Tragedies of Shakspeare,” “On the Genius and Character of Hogarth,” and “Recollections of Christ’s Hospital.” Table Of Contents CONTENTS . 3 RECOLLECTIONS OF CHRIST’S HOSPITAL . 4 ON THE TRAGEDIES OF SHAKSPEARE . 13 SPECIMENS FROM THE WRITINGS OF FULLER, THE CHURCH HISTORIAN . 25 ON THE GENIUS AND CHARACTER OF HOGARTH; WITH SOME REMARKS ON A PASSAGE IN THE WRITINGS OF THE LATE MR. BARRY . 31 ON THE POETICAL WORKS OF GEORGE WITHER 45 THE END OF THE ESSAYS OF CHARLES LAMB . 48 CONTENTS Recollections of Christ’s Hospital On the Tragedies of Shakspeare Specimens for the Writings of Fuller On the genius and Character of hogarth On the Poetical Works of George Wither RECOLLECTIONS OF CHRIST’S HOSPITAL To comfort the desponding parent with the thought that, without diminishing the stock which is imperiously demanded to furnish the more pressing and homely wants of our nature, he has disposed of one or more perhaps out of a numerous offspring, under the shelter of a care scarce less tender than the paternal, where not only their bodily cravings shall be supplied, but that mental pabulum is also dispensed, which HE hath declared to be no less necessary to our sustenance, who said, that, “not by bread alone man can live”: for this Christ’s Hospital unfolds her bounty.