Paris, New York, and Post-National Romance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reid Hall Columbia Global Centers | Paris

Reid Hall Reid Academic Year 2016 – 2017 Columbia Global Centers | Paris Annual Report “ The best semester of my life.” DIEGO RODRIGUEZ, ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM Contents “During my time at Reid Hall, I not only benefited from exceptional professors from Columbia’s campus and at Paris IV, but also had my perspective of the world drastically expanded. Advisory Board & Faculty Steering Committee 2 Between living with host families and interacting Letter from President Lee C. Bollinger 4 with other students—both those in my program Letter from EVP Safwan M. Masri 5 and those at French universities—I gained the Introduction, Paul LeClerc, Director 6 ability to analyze and critique the American and Reid Hall, Une réhabilitation, the French ways of life. I became so enamored Brunhilde Biebuyck, Administrative Director 10 by the latter that, while initially only intending to The Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination 13 Fall, Spring, & Summer Academic Programs 16 spend one semester MA in History and Literature 16 Whether or not a The Shape of Two Cities: Paris Spring Term 20 abroad, I have Columbia Undergraduate Programs in Paris, Fall & Spring Terms 22 chosen to stay in student intends Columbia Undergraduate Programs in Paris, France to continue Summer Term 25 to do the same, Other Summer Academic Programs 27 my studies. Alliance Graduate Summer School 27 I recommend a Senior Thesis Research in Europe 30 Public Programs 31 study abroad at Paris Center Programming 31 Columbia Sounds at Reid Hall 33 Reid Hall without Columbia University Alumni Club of France 34 Programs Organized by CGC l Paris 36 ” hesitation. -

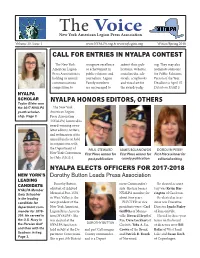

NYALPA Voice (Spring 2018 Issue)

The Voice New York American Legion Press Association Volume 20, Issue 1 www.NYALPA.org & www.nylegion.org Winter/Spring 2018 CALL FOR ENTRIES IN NYALPA CONTEST The New York recognize excellence submit their pub- ing. They may also American Legion or achievement in lications, websites, nominate someone Press Association is public relations and social media, edi- for Public Relations holding its annual journalism. Legion torials, scrapbooks Person of the Year. communications Family members and visual art for Deadline is April 15. competition to are encouraged to the awards judg- Details on PAGE 5. NYALPA SCHOLAR NYALPA HONORS EDITORS, OTHERS Taylor Blake won the 2017 NYALPA The New York youth scholar- American Legion ship. Page 3. Press Association (NYALPA) honored its award-winning news- letter editors, writers, and webmasters at its annual luncheon held in conjunction with the Department of PAUL STEWARD JAMES BOJANOWSKI DOROLYN PERRY New York Convention First Place winner for First Place winner for First Place winner for last July. PAGE 4 post publication county publication editorial writing NYALPA ELECTS OFFICERS FOR 2017-2018 NEW YORK’S Dorothy Button Leads Press Association LEADING CANDIDATE Dorothy Button, ment Commander’s Re-elected as secre- adjutant of Ashford aide. She has been a tary was Kevin Har- NYALPA Member Gary Schacher Memorial Post 1576 NYALPA member for rington of Castleton. is the leading in West Valley, is the about four years. Re-elected as trea- candidate for new president of the ELECTED as vice surer was Executive department com- New York American presidents were:: Carl Director Lynda Pixley mander for 2018- Legion Press Associa- Griffiths of Munns- of Ransomville. -

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism With

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism with Friends In the years that followed the completion of its initial broadcast run, which came to an end on 6th (S10 E17 and 18), iconicMay millennial with USthe sitcom airing ofFriends the tenth (NBC season 1994-2004) finale The generated Last One only a moderate amount of scholarly writing. Most of it tended to deal with the series st- principally-- appointment in terms of its viewing institutional of the kindcontext, that and was to prevalent discuss it in as 1990s an example television of mu culture.see TV This, of course, was prior to the widespread normalization of time-shifted viewing practices to which the online era has since given rise (Lotz 2007, 261-274; Curtin and Shattuc 2009, 49; Gillan 2011, 181). Friends was also the subject of a small number of pieces of scholarship that entriesinterrogated that emerged the shows in thenegotiation mid-2000s of theincluded cultural politics of gender. Some noteworthy discussion of its liberal feminist individualism, and, for what example, she argued Naomi toRocklers be the postfeminist depoliticization of the hollow feminist rhetoric that intermittently rose to der, and in its treatment of prominence in the shows hierarchy of discourses of gen thatwomens interrogated issues . issues Theand sameproblems year arising also saw from the some publication of the limitationsof work by inherentKelly Kessler to ies (2006). The same year also sawthe shows acknowledgement depiction and in treatmenta piece by offeminist queer femininittelevision scholars Janet McCabe and Kim Akass of the significance of Friends as a key text of postfeminist television culture (2006). -

Kissing Co-Stars: on and Off-Screen Celebrity Couples

Kissing Co-Stars: On and Off- Screen Celebrity Couples By Katie Gray When couples on-screen become real celebrity couples off- screen, we get extra excited. What could be better than falling in love with a movie relationship, and then learning that it is actually a reality? It’s a fairy tale come true when it becomes an actual celebrity relationship! Whether the relationships last or are just a fling, it’s fun while it lasts. In many cases, it’s ended in celebrity weddings and celebrity babies. We can all take a cue andrelationship advice from these cute celeb couples who show us love on and off-screen! Cupid has compiled our six favorite on and off-screen celebrity couples: 1. Ben Affleck & Jennifer Garner: This celebrity couple met on the set of Daredevil and ended up getting married and having children together. They married in 2005 in Turks and Caicos and have three children together: Violet, Seraphina and Samuel. They announced they were divorcing in 2015, but they remain friends and family because of their offspring. Garner has also dated previous co-stars such as Alias co-star Michael Vartan, and she was even married to Scott Foley for three years after meeting him on the set of his seriesFelicity . It’s true that love can be found on set! 2. Brad Pitt & Angelina Jolie: Everybody loves Brangelina! This celebrity couple met while filming Mr. & Mrs. Smith together and caused a big stir, as speculation stirred that an affair happened between the two while Pitt was still married to Jennifer Aniston. -

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway by Nate Jones

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway By Nate Jones Spend a few minutes reading blog comments, and you might assume that Anne Hathaway’s approval rating falls somewhere between that of Boko Haram and paper cuts — but you'd actually be completely wrong. According to E-Poll likability data we factored into Vulture's Most Valuable Stars list, the braying hordes of Hathaway haters are merely a very vocal minority. The numbers say that most people actually like her. Even more shocking? Who they like her more than. In calculating their E-Score Celebrity rankings, E-Poll asked people how much they like a particular celebrity on a six-point scale, which ranged from "like a lot" to "dislike a lot." The resulting Likability percentage is the number of respondents who indicated they either "like" Anne Hathaway or "like Anne Hathaway a lot." Hathaway's 2014 Likability percentage was 67 percent — up from 66 percent in 2013 — which doesn't quite make her Will Smith (85 percent), Sandra Bullock (83 percent), Jennifer Lawrence (76 percent), or even Liam Neeson (79 percent), but it does put her well above plenty of stars whose appeal has never been so furiously impugned on Twitter. Why? Well, why not? Anne Hathaway is a talented actress and seemingly a nice person. The objections to her boiled down to two main points: She tries too hard, and she's overexposed. But she's been absent from the screen since 2012'sLes Misérables, so it's hard to call her overexposed now. And trying too hard isn't the worst thing in the world, especially when you consider the alternative. -

22Nd NFF Announces Screenwriters Tribute

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NANTUCKET FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES TOM MCCARTHY TO RECEIVE 2017 SCREENWRITERS TRIBUTE AWARD NICK BROOMFIELD TO BE RECOGNIZED WITH SPECIAL ACHIEVEMENT IN DOCUMENTARY STORYTELLING NFF WILL ALSO HONOR LEGENDARY TV CREATORS/WRITERS DAVID CRANE AND JEFFREY KLARIK WITH THE CREATIVE IMPACT IN TELEVISION WRITING AWARD New York, NY (April 6, 2017) – The Nantucket Film Festival announced today the honorees who will be celebrated at this year’s Screenwriters Tribute—including Oscar®-winning writer/director Tom McCarthy, legendary documentary filmmaker Nick Broomfield, and ground-breaking television creators and Emmy-nominated writing team David Crane and Jeffrey Klarik. The 22nd Nantucket Film Festival (NFF) will take place June 21-26, 2017, and celebrates the art of screenwriting and storytelling in cinema and television. The 2017 Screenwriters Tribute Award will be presented to screenwriter/director Tom McCarthy. McCarthy's most recent film Spotlight was awarded the Oscar for Best Picture and won him (and his co-writer Josh Singer) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. McCarthy began his career as a working actor until he burst onto the filmmaking scene with his critically acclaimed first feature The Station Agent, starring Peter Dinklage, Patricia Clarkson, Bobby Cannavale, and Michelle Williams. McCarthy followed this with the equally acclaimed film The Visitor, for which he won the Spirit Award for Best Director. He also shared story credit with Pete Docter and Bob Peterson on the award-winning animated feature Up. Previous recipients of the Screenwriters Tribute Award include Oliver Stone, David O. Russell, Judd Apatow, Paul Haggis, Aaron Sorkin, Nancy Meyers and Steve Martin, among others. -

Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~

KEEPING UP WITH THE JONESES: SOCIOECONOMIC CLASS REPRESENTATION IN SITCOMS by ALEXANDRA HICKS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2014 A• Abstracto( the Thesis of Alexandra Hicks for 1he degree ofBachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be talcen June, 2014 Title: Keeping Up With the Jonescs: Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~ This thesis examines the representation of socioeconomic class in situation comedies. Through the influence of the advertising industiy, situation comedies (sitcoms) have developed a pattem throughout history of misrepresenting ~ial class, which is made evident by their portrayals ofdifferent races, genders, and professions. To rectify the IKk ofprevious studies on modem comedies, this study analyzes socioeconomic class representation on sitcoms that have aired in the last JS years by taking a sample ofseven shows and comparing the estimated cost of characters' residences to the amount of money they would likely earn in their given profession. 1be study showed that modem situation comedies misrepresent socioeconomic class by portraying characters living in residences well beyond what they could afford in real life. Accurate demonstration ofsocioeconomic class on television is imperative be<:ause images presented on television genuinely influence viewers• perceptions of reality. Inaccurate portrayals ofclass could cause audiences to develop distorted views ofmember.; of socioeconomic classes and themselves. u Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Debra Merskin for inspiring me to examine television in an in-depth and critical manner. -

Cole Porter: the Social Significance of Selected Love Lyrics of the 1930S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository Cole Porter: the social significance of selected love lyrics of the 1930s by MARILYN JUNE HOLLOWAY submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject of ENGLISH at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IA RABINOWITZ November 2010 DECLARATION i SUMMARY This dissertation examines selected love lyrics composed during the 1930s by Cole Porter, whose witty and urbane music epitomized the Golden era of American light music. These lyrics present an interesting paradox – a man who longed for his music to be accepted by the American public, yet remained indifferent to the social mores of the time. Porter offered trenchant social commentary aimed at a society restricted by social taboos and cultural conventions. The argument develops systematically through a chronological and contextual study of the influences of people and events on a man and his music. The prosodic intonation and imagistic texture of the lyrics demonstrate an intimate correlation between personality and composition which, in turn, is supported by the biographical content. KEY WORDS: Broadway, Cole Porter, early Hollywood musicals, gays and musicals, innuendo, musical comedy, social taboos, song lyrics, Tin Pan Alley, 1930 film censorship ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I should like to thank Professor Ivan Rabinowitz, my supervisor, who has been both my mentor and an unfailing source of encouragement; Dawie Malan who was so patient in sourcing material from libraries around the world with remarkable fortitude and good humour; Dr Robin Lee who suggested the title of my dissertation; Dr Elspa Hovgaard who provided academic and helpful comment; my husband, Henry Holloway, a musicologist of world renown, who had to share me with another man for three years; and the man himself, Cole Porter, whose lyrics have thrilled, and will continue to thrill, music lovers with their sophistication and wit. -

Accepted Manuscript Version

Research Archive Citation for published version: Kim Akass, and Janet McCabe, ‘HBO and the Aristocracy of Contemporary TV Culture: affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007’, Mise au Point, Vol. 10, 2018. DOI: Link to published article in journal's website Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: This manuscript version is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives License CC BY NC-ND 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact Research & Scholarly Communications at [email protected] 1 HBO and the Aristocracy of TV Culture : affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007 Kim Akass and Janet McCabe In its institutional pledge, as Jeff Bewkes, former-CEO of HBO put it, to ‘produce bold, really distinctive television’ (quoted in LaBarre 90), the premiere US, pay- TV cable company HBO has done more than most to define what ‘original programming’ might mean and look like in the contemporary TV age of international television flow, global media trends and filiations. In this article we will explore how HBO came to legitimatise a contemporary television culture through producing distinct divisions ad infinitum, framed as being rooted outside mainstream commercial television production. In creating incessant divisions in genre, authorship and aesthetics, HBO incorporates artistic norms and principles of evaluation and puts them into circulation as a succession of oppositions— oppositions that we will explore throughout this paper. -

Jennifer Aniston, Jimmy Kimmel Face Fire Scare on Stage at 2020 Emmy Awards

Jennifer Aniston, Jimmy Kimmel face fire scare on stage at 2020 Emmy Awards foxnews.com/entertainment/jennifer-aniston-jimmy-kimmel-fire-scare-2020-emmy-awards The stage was on fire at the 2020 Emmy Awards on Sunday night. The show kicked off with a handful of jokes about coronavirus and the subsequent quarantine by host Jimmy Kimmel before he was joined on stage by Jennifer Aniston to present the award for best lead actress. The bit began with Kimmel, 52, donning rubber gloves to douse the envelope containing the winner's name in a disinfectant spray. To further the joke, they placed the envelope in a wastebasket and lit it on fire. The "Friends" alum, 51, was handed a fire extinguisher and blasted the firey bin. The first blast didn't take, however, as the fire rose up again before Kimmel could retrieve the envelope, so she jumped to action again. The star sprayed the envelope a third time as the comedian was using tongs to pull the slip from the bin. Once the envelope was safely removed from the bin, the pair turned their attention back to the bit, but once again, flames rose from the wastebasket. Quick on her feet, Aniston put out the fire once and for all. Jennifer Aniston puts out a fire in a wastebasket with Jimmy Kimmel at the 2020 Emmy Awards. (ABC/Image Group LA via Getty) Kimmel Tweeted after the ordeal. "THANK GOD FOR JENNIFER ANISTON!" he said, sharing a photo of the star in action. The bit came after Kimmel explained that each of the nominees will be at remote locations, such as their homes, and the winners would receive their awards in real-time.