Socioeconomic Class Representation in Sitcoms Awroa:&~

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Advocacy. Fighting Defamation. Changing Hearts and Minds

GAY & LESBIAN AllIANCE AgAINST DEFAMATION PERFORMANCE REPORT 2007 Media Advocacy. Fighting Defamation. Changing Hearts and Minds. Personal Stories That Move Public Opinion 70280_GLAAD_r2.indd 1 6/26/08 1:04:19 PM GLAAD PERFORMANCE REPORT 2007 1 Letter from the President 1 Letter from the National Board Co-Chairs 2 Changing Hearts and Minds: Harnessing the Power of the Media to Move Public Opinion 8 Media Advocacy: Focused on Issues of Faith 14 Fighting Defamation: Holding Media Accountable 20 Timeline of Accomplishments 23 18th Annual GLAAD Media Awards 24 Support 30 Independent Auditors’ Report 31 Financial Statements 32 Board of Directors, Staff, Media Fellowships and Internships 70280_GLAAD_r2.indd 2 6/26/08 1:04:19 PM GLAAD PERFORMANCE REPORT 2007 1 Letter from the President Letter from the National Board Co-Chairs I often say that how our lives are portrayed in the media doesn’t On behalf of the GLAAD National Board of Directors and our make a bit of difference; it makes all the difference. Media advocacy, senior volunteers across the country, we are pleased and proud fighting defamation, and changing hearts and minds are at the to offer you this Performance Report for 2007. core of GLAAD ’s mission. Throughout 2007 and for over 22 years, GLAAD has met significant programmatic and operational our culture-changing work has helped empower Americans who milestones in 2007 that are critical to our continued success believe in fairness for all people. The visibility of the lesbian, gay, as the LGBT community’s national media advocacy and anti- bisexual and transgender (LGBT ) community, telling our individual defamation organization. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism With

The One with the Feminist Critique: Revisiting Millennial Postfeminism with Friends In the years that followed the completion of its initial broadcast run, which came to an end on 6th (S10 E17 and 18), iconicMay millennial with USthe sitcom airing ofFriends the tenth (NBC season 1994-2004) finale The generated Last One only a moderate amount of scholarly writing. Most of it tended to deal with the series st- principally-- appointment in terms of its viewing institutional of the kindcontext, that and was to prevalent discuss it in as 1990s an example television of mu culture.see TV This, of course, was prior to the widespread normalization of time-shifted viewing practices to which the online era has since given rise (Lotz 2007, 261-274; Curtin and Shattuc 2009, 49; Gillan 2011, 181). Friends was also the subject of a small number of pieces of scholarship that entriesinterrogated that emerged the shows in thenegotiation mid-2000s of theincluded cultural politics of gender. Some noteworthy discussion of its liberal feminist individualism, and, for what example, she argued Naomi toRocklers be the postfeminist depoliticization of the hollow feminist rhetoric that intermittently rose to der, and in its treatment of prominence in the shows hierarchy of discourses of gen thatwomens interrogated issues . issues Theand sameproblems year arising also saw from the some publication of the limitationsof work by inherentKelly Kessler to ies (2006). The same year also sawthe shows acknowledgement depiction and in treatmenta piece by offeminist queer femininittelevision scholars Janet McCabe and Kim Akass of the significance of Friends as a key text of postfeminist television culture (2006). -

REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: the Big Bang Theory Reconsidered REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: Many Studies Define “Nerdiness” Differently

ARTICLE Title REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: The Big Bang Theory Reconsidered REDEFINING “NERDINESS”: Many studies define “nerdiness” differently. Some textual cues including explicit and implicit cues. These would define gifted students as “nerds” (O’Connor 293), terms are adopted from Culpeper’s The Language and The Big Bang Theory Reconsidered suggesting that the word is based solely on intelligence. Characterisation: People in Plays and Other Texts, in which he Others may define “nerds” as “physical self-loathing [and explains that these textual cues can help a viewer make having] technological mastery” (Eglash 49), suggesting certain inferences about a specific character (Language that “nerds” have body issues or are somehow more and Characterisation 167). Explicit cues are when charac- BY JACLYN GINGRICH technologically savvy than the average person. Bednarek ters specifically express information about themselves or defines “nerdiness” as displaying the following linguistic others (Language of Characterisation 167). An example framework: “believes in his own intelligence,” “was a child would be when Leonard says, “Yeah, I’m a frickin’ genius” ABSTRACT it is that they are average people socializing with each prodigy,” “struggles with social skills,” “is different,” “is health (“The Middle Earth Paradigm”). Here he is explicitly other and living normal lives. The Big Bang Theory displays This paper analyzes the linguistic characteristics of Leonard obsessed/has food issues,” “has an affinity for and knowl- saying that he believes he has intellectual superiority. the comical reality of what normally happens in these Hofstadter, television character from The Big Bang Theory and edge of computer-related activities,” “does not like change,” Implicit cues are implied. -

AGE Qualitative Summary

AGE Qualitative Summary Age Gender Race 16 Male White (not Hispanic) 16 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 17 Male Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 18 Malel Blacklk or Africanf American (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female White (not Hispanic) 18 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 18 Male White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 19 Female Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female White (p(not Hispanic)) 19 Male Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female Hispanic (unspecified) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Female White (not Hispanic) 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 19 Female Other 19 Male Hispanic/Latino – White 19 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 20 Female White (not Hispanic) 20 Female Other 20 Female Black or African American (not Hispanic) 20 Male Other 20 Male Native American or Alaskan Native 21 Female Don’t want to respond 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Female White (not Hispanic) 21 Male Asian, Asian Indian, or Pacific Islander 21 Female White (not -

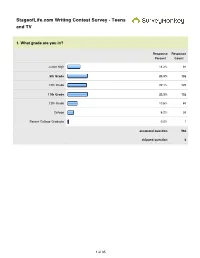

Stageoflife.Com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV

StageofLife.com Writing Contest Survey - Teens and TV 1. What grade are you in? Response Response Percent Count Junior High 14.3% 81 9th Grade 23.3% 132 10th Grade 22.1% 125 11th Grade 23.3% 132 12th Grade 10.6% 60 College 6.2% 35 Recent College Graduate 0.2% 1 answered question 566 skipped question 0 1 of 35 2. How many TV shows (30 - 60 minutes) do you watch in an average week during the school year? Response Response Percent Count 20+ (approx 3 shows per day) 21.7% 123 14 (approx 2 shows per day) 11.3% 64 10 (approx 1.5 shows per day) 9.0% 51 7 (approx. 1 show per day) 15.7% 89 3 (approx. 1 show every other 25.8% 146 day) 1 (you watch one show a week) 14.5% 82 0 (you never watch TV) 1.9% 11 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3. Do you watch TV before you leave for school in the morning? Response Response Percent Count Yes 15.7% 89 No 84.3% 477 answered question 566 skipped question 0 2 of 35 4. Do you have a TV in your bedroom? Response Response Percent Count Yes 38.7% 219 No 61.3% 347 answered question 566 skipped question 0 5. Do you watch TV with your parents? Response Response Percent Count Yes 60.6% 343 No 39.4% 223 If yes, which show(s) do you watch as a family? 302 answered question 566 skipped question 0 6. Overall, do you think TV is too violent? Response Response Percent Count Yes 28.3% 160 No 71.7% 406 answered question 566 skipped question 0 3 of 35 7. -

The Walking Dead,” Which Starts Its Final We Are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant Season Sunday on AMC

Las Cruces Transportation August 20 - 26, 2021 YOUR RIDE. YOUR WAY. Las Cruces Shuttle – Taxi Charter – Courier Veteran Owned and Operated Since 1985. Jeffrey Dean Morgan Call us to make is among the stars of a reservation today! “The Walking Dead,” which starts its final We are Covid-19 Safe-Practice Compliant season Sunday on AMC. Call us at 800-288-1784 or for more details 2 x 5.5” ad visit www.lascrucesshuttle.com PHARMACY Providing local, full-service pharmacy needs for all types of facilities. • Assisted Living • Hospice • Long-term care • DD Waiver • Skilled Nursing and more Life for ‘The Walking Dead’ is Call us today! 575-288-1412 Ask your provider if they utilize the many benefits of XR Innovations, such as: Blister or multi-dose packaging, OTC’s & FREE Delivery. almost up as Season 11 starts Learn more about what we do at www.rxinnovationslc.net2 x 4” ad 2 Your Bulletin TV & Entertainment pullout section August 20 - 26, 2021 What’s Available NOW On “Movie: We Broke Up” “Movie: The Virtuoso” “Movie: Vacation Friends” “Movie: Four Good Days” From director Jeff Rosenberg (“Hacks,” Anson Mount (“Hell on Wheels”) heads a From director Clay Tarver (“Silicon Glenn Close reunited with her “Albert “Relative Obscurity”) comes this 2021 talented cast in this 2021 actioner that casts Valley”) comes this comedy movie about Nobbs” director Rodrigo Garcia for this comedy about Lori and Doug (Aya Cash, him as a professional assassin who grapples a straight-laced couple who let loose on a 2020 drama that casts her as Deb, a mother “You’re the Worst,” and William Jackson with his conscience and an assortment of week of uninhibited fun and debauchery who must help her addict daughter Molly Harper, “The Good Place”), who break up enemies as he tries to complete his latest after befriending a thrill-seeking couple (Mila Kunis, “Black Swan”) through four days before her sister’s wedding but decide job. -

'Perry Mason' Lays Down the Law Anew On

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! June 19 - 25, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 E A D T Y E A W A H P Y F A Z Your Key I J P E C L K S N Z R A E T C 2 x 3" ad To Buying R E Q I P L Y U G R P O U E Y Matthew Rhys stars P F L U J R H A E L Y N P L R and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad F A R H O W E P L I T H G O W in “Perry Mason,” I F Y P N M A S E P Z X T J E premiering Sunday D E L L A Z R E S S E A M A G on HBO. Z P A R T R Y D L I G N S U S B F N Y H N E M H I O X L N N E R C H A L K D T J L N I A Y U R E L N X P S Y E Q G Y R F V T S R E D E M P T I O N H E E A Z P A V R J Z R W P E Y D M Y L U N L H Z O X A R Y S I A V E I F C I P W K R U V A H “Perry Mason” on HBO Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Perry (Mason) (Matthew) Rhys (Great) Depression Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Della (Street) (Juliet) Rylance (Los) Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Paul (Drake) (Chris) Chalk Origins Midlothian Mirror and Ellis (Sister) Alice (Tatiana) Maslany (Private) Investigator County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search (E.B.) Jonathan (John) Lithgow Redemption Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘Perry Mason’ lays down for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light, 3.5" ad Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Interpretation of Verbal Humor in the Sitcom the Big Bang Theory from the Perspective of Adaptation-Relevance Theory

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 3, No. 12, pp. 2220-2226, December 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.12.2220-2226 Interpretation of Verbal Humor in the Sitcom The Big Bang Theory from the Perspective of Adaptation-relevance Theory Zejun Ma School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China Man Jiang School of Foreign Languages, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China Abstract—Humor plays a very important role in every sphere of our daily life, especially verbal humor which is mainly carried by language use in a certain context to achieve humorous effect. As a special carrier of humor, sitcom, which is a type of comedy performance, has attracted millions of audiences with humorous utterances all over the world. The American sitcom The Big Bang Theory has been one of the most popular American sitcoms in China within these years which largely count on verbal humor to create general humorous effect. Based on the achievements made by previous researchers, the present study explores the verbal humor in the American sitcom The Big Bang Theory in the light of a new model—Adaptation-Relevance model so as to reveal its interpretive power of humor and its feasibility in analyzing verbal humor in the sitcom The Big Bang Theory. The paper mainly adopts the qualitative and descriptive methods to analyze the selected examples and finally comes to a conclusion that this Adaptation-Relevance model which is an integration of two powerful pragmatic theories holds the interpretive power for verbal humor and has feasibility in analyzing verbal humor by using the data in sitcom The Big Bang Theory. -

Paris, New York, and Post-National Romance

Sex and the Series: Paris, New York, and Post-National Romance Dana Heller / love Paris every moment, Every moment of the year I love Paris, why oh why do I love Paris? Because my love is here. —Cole Porter, / Love Paris This essay will examine and contrast two recent popular situation comedies, NBC's Friends and HBO's Sex and the City, as narratives that participate in the long-standing utilization of Paris as trope, or as an instrumental figure within the perennially deformed and reformed landscape of the American national imaginary. My argument is that Paris re-emerges in post-9/11 popular culture as a complex, multi-accentual figure within the imagined mise-en-scene of the world Americans desire. The reasons for this are to a large degree historical: in literature, cinema, television, popular music, and other forms of U.S. cultural production, from the late nineteenth century through the twentieth century and into the twenty first, Paris has remained that city where one ventures, literally and/or imaginatively, to dismember history, or to perform a disarticulation of the national subject that suggests possibilities for the interrogation of national myths and for 0026-3079/2005/4602-145$2.50/0 American Studies, 46:1 (Summer 2005): 145-169 145 146 Dana Heller the articulation of possible new forms of national unity and allegiance. These forms frequently find expression in the romantic transformation of a national citizen-subject into a citizen-subject of the world, a critique of the imperialist aspirations of the nation-state that antithetically masks those same aspirations under the sign of the disillusioned American cosmopolitan abroad. -

60 Minutes/Vanity Fair Poll June 12-16, 2013

60 Minutes/Vanity Fair Poll June 12-16, 2013 Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “All women eventually become just like their mother.” Most Americans think women can avoid becoming just like their moms. According to most Americans, all women are not destined to follow in their mother’s footsteps. While 23% agreed with the statement that all women become just like their mother, three in four said this was not true. There is little difference by age or gender. Better educated Americans are less likely to be fatalistic on this matter. While 26% of Americans without a college degree said that all women eventually become just like their mother, this percentage drops to 20% for those with college degrees and 14% for those with some post graduate studies. “All Women Eventually Become Their Mothers” Total No College Post Respondents Degree Degree Grads Agree 23% 26% 20% 14% Disagree 74 72 78 83 Do you agree or disagree with the following statement? – “A good woman is hard to find” Most men think a good woman is hard to find, though women aren’t so sure. Most Americans think a good woman is hard to find. Overall, 57% of Americans think so, though women are not as likely to say so as men. While six in 10 men think a good woman is hard to find, just half of women agree. “A Good Woman is Hard to Find” Total Men Women Agree 57% 63% 50% Disagree 42 35 48 Those having trouble finding a good woman may want to head west.