9769 SP5A.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975)

CARTER, JOHN MARSHALL. The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975). Directed by: Prof. John H. Beeler. The purpose of this study was to investigate the historical accounts of the Norman Conquest and its results. A select group of historians and works, primarily English, were investigated, beginning with the chronicles of medieval writers and continuing chronologically to the works of twentieth century historians. The majority of the texts that were examined pertained to the major problems of the Norman Conquest: the introduction of English feudalism, whether or not the Norman Conquest was an aristocratic revolution, and, how it affected the English church. However, other important areas such as the Conquest's effects on literature, language, economics, and architecture were observed through the "eyes" of past and present historians. A seconday purpose was to assemble for the student of English medieval history, and particularly the Norman Conquest, a variety of primary and secondary sources. Each new generation writes its own histories, seeking to add to the existing cache of material or to reinterpret the existing material in the light of the present. The future study of history will be significantly advanced by historiographic surveys of all major historical events. Professor Wallace K. Ferguson produced an indispensable work for students of the Italian Renaissance, tracing the development of historical thought from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. V Professor Bryce Lyon performed a similar task,if not on as epic a scale, with his essay on the diversity of thought in regard to the history of the origins of the Middle Ages. -

The Norman Conquest

OCR SHP GCSE THE NORMAN CONQUEST NORMAN THE OCR SHP 1065–1087 GCSE THE NORMAN MICHAEL FORDHAM CONQUEST 1065–1087 MICHAEL FORDHAM The Schools History Project Set up in 1972 to bring new life to history for school students, the Schools CONTENTS History Project has been based at Leeds Trinity University since 1978. SHP continues to play an innovatory role in history education based on its six principles: ● Making history meaningful for young people ● Engaging in historical enquiry ● Developing broad and deep knowledge ● Studying the historic environment Introduction 2 ● Promoting diversity and inclusion ● Supporting rigorous and enjoyable learning Making the most of this book These principles are embedded in the resources which SHP produces in Embroidering the truth? 6 partnership with Hodder Education to support history at Key Stage 3, GCSE (SHP OCR B) and A level. The Schools History Project contributes to national debate about school history. It strives to challenge, support and inspire 1 Too good to be true? 8 teachers through its published resources, conferences and website: http:// What was Anglo-Saxon England really like in 1065? www.schoolshistoryproject.org.uk Closer look 1– Worth a thousand words The wording and sentence structure of some written sources have been adapted and simplified to make them accessible to all pupils while faithfully preserving the sense of the original. 2 ‘Lucky Bastard’? 26 The publishers thank OCR for permission to use specimen exam questions on pages [########] from OCR’s GCSE (9–1) History B (Schools What made William a conqueror in 1066? History Project) © OCR 2016. OCR have neither seen nor commented upon Closer look 2 – Who says so? any model answers or exam guidance related to these questions. -

Frank Barlow 1911–2009

FRANK BARLOW Frank Barlow 1911–2009 FRANK BARLOW was born on 19 April 1911, the eldest son of Percy Hawthorn Barlow and Margaret Julia Wilkinson, who had married in 1910. In his nineties he wrote a memoir, which is mostly devoted to describing his childhood and adolescence and his experiences during the Second World War, and which is now included among his personal and professional papers. He also kept many papers and memorabilia from his childhood and youth and he preserved meticulously his professional papers. His numerous publications include fi fteen books and scholarly editions, of which many have turned out to be of quite exceptional long- term importance. He is notable above all for three outstandingly important historical biographies, for the excellence of his editions and interpreta- tions of diffi cult Latin texts, and for a textbook that has remained in print for more than half a century. His interest in literature, present from an early age, and his belief that historical research and writing, while being conducted according to the most exacting scholarly standards, should be approached as a branch of literature, made him a historian whose appeal was literary as well as conventionally historical. He used biography as a means not just to understand an individual but also as the basis from which to interpret broad historical issues and to refl ect on the mysteries of the human condition. In his hands, the edition of a Latin text was also a means to literary expression, with the text’s meaning elucidated percep- tively and imaginatively and the translation being every bit as much a work of literature as the original text. -

Family Lines from Companions of the Conqueror

Companions of the Conqueror and the Conqueror 1 Those Companions of William the Conqueror From Whom Ralph Edward Griswold and Madge Elaine Turner Are Descended and Their Descents from The Conqueror Himself 18 May 2002 Note: This is a working document. The lines were copied quickly out of the Griswold-Turner data base and have not yet been retraced. They have cer- tainly not been proved by the accepted sources. This is a massive project that is done in pieces, and when one piece is done it is necessary to put it aside for a while before gaining the energy and enthusiasm to continue. It will be a working document for some time to come. This document also does not contain all the descents through the Turner or Newton Lines 2 Many men (women are not mentioned) accompanied William the Conqueror on his invasion of England. Many men and women have claimed to be descended from one or more of the= Only a few of these persons are documented; they were the leaders and colleagues of William of Normandy who were of sufficient note to have been recorded. Various sources for the names of “companions” (those who were immediate associates and were rewarded with land and responsibility in England) exist. Not all of them have been consulted for this document. New material is in preparation by reputable scholars that will aid researchers in this task. For the present we have used a list from J. R. Planché. The Conqueror and His Companions. Somerset Herald. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1874.. The persons listed here are not the complete list but constitute a subset from which either Ralph Edward Griswold or Madge Elaine Turner (or both) are descended). -

Shirley Ann Brown

Shirley Ann Brown The Bayeux Tapestry and the Song of Roland RITING AROUND 1067, Guy of Amiens described in his Carmen de W Hastingae Proelio how a certain "mimus" rode before the assem- bled French troops at Hastings and juggled with his sword. The purpose of this bravado performance was to hearten the French and terrify the English. An infuriated English knight rode forward to rid the field of this arrogant intruder, but he was swept from his horse by the lance of "Incisor-ferri" and, losing his head, became instead the first trophy of the battle.1 Some sixty years later the incident had assumed a different dimension when William of Malmesbury indicated that the story of Roland was sung before the French at Hastings to serve as an example of valour to those who were about to face a fight that could end only in victory or death.2 It is not surprising that Wace, writing between 1160 and 1174, combined the two stories, and that the juggling knight "Taillefer" was said to have had the Song of Roland on his lips as he faced the army. All that this proves, of course, is that the story of Roland's valor and death at Roncevaux was a popular model of military heroism during the twelfth century. It is difficult to imagine how the poem, as we have it, could have been performed while two armies were poised and ready to attack each other. Nevertheless, the Song of Roland has been associated with the Normans and Hastings by many subsequent historians. -

A Model of Wisdom and Exemplar of Modesty Without Parallel in Our Time”: How Matilda of Flanders Was Represented in Two Twelfth-Century Histories

“A model of wisdom and exemplar of modesty without parallel in our time”: how Matilda of Flanders was represented in two twelfth-century histories. Alexandra Lee Pierce Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in History (by Thesis Only) December 2010 School of Historical Studies The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract Matilda of Flanders was the wife of William the Conqueror, and as such was the first Anglo-Norman queen of England. Coming from an important family with connections to the French royal family, she played a crucial role in the new Anglo-Norman kingdom. As well as being a duchess and a queen, Matilda was also important as a monastic benefactor and as the mother of eight children, a number of whom went on to play important roles. My thesis investigates the different ways in which two twelfth-century historians, William of Malmesbury and Orderic Vitalis, represented Matilda. Beginning with an understanding that women in medieval historical texts are an ‘imaginative construction,’ it examines how these two near-contemporary historians constructed Matilda’s image to reinforce their own overall purposes. My discussion of how Matilda was represented is divided into three chapters. The first chapter examines how the two historians represented Matilda through family connections. Her marital relationship with William was the most important to both historians; how Malmesbury and Orderic represented her relationships with her children and her natal family is also examined. The second chapter is concerned with representations of Matilda through political activities, as duchess and queen. -

John Howe on the &Quot;Carmen De Hastingae Proelio&Quot; Of

Frank Barlow, ed.. The "Carmen de Hastingae Proelio" of Guy Bishop of Amiens. New York and Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999. xciv + 55 pp. $73.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-820758-0. Reviewed by John Howe Published on H-Catholic (September, 2000) The "Carmen de Hastingae Proelio" (the "Song forward" transcription--is little changed from the of the Battle of Hastings") is a poem of 835 surviv‐ original Oxford text presented by the late Cather‐ ing Virgilian lines, known basically from a single ine Morton and Hope Munz in 1972; the new copy in Brussels BR ms. 10615-729, fols. 227v-230v, translation is slightly less purple and more literal an early twelfth-century miscellaneous anthology than theirs; the introduction has been almost en‐ from the Abbey of St. Eucharius-Matthias in Trier tirely redone. (a medieval direct copy of 66 lines also survives, For both professional historians and ama‐ but lacks independent textual value). The Carmen teurs interested in "1066 and all that," the Carmen describes William the Conqueror's invasion of might seem somewhat disappointing. Form, me‐ England from the arrival of his feet at Saint- ter, and heroic mode eclipse concrete detail. Of Valery-sur-Somme until his coronation at West‐ the departure, for example we read that: minster (i.e. the events from September through ... all arrive rejoicing, and run instantly to December of 1066, where the text breaks off). Al‐ take up position. Some step the masts, others hoist though the surviving poem is anonymous and un‐ the sails. Many force the knights' horses to clam‐ titled, it has been identified as the "metricum car‐ ber on to the ships. -

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson “Harold II” redirects here. For other uses, see Harald II. ing to secure the English throne for Edward the Confes- sor. In 1045, Godwin was at the height of his power, when his daughter Edith was married to the king.[8] Harold II (or Harold Godwinson)(Old English: Harold Godƿinson; c. 1022 – 14 October 1066) was the last Godwin and Gytha had several children. The sons were Anglo-Saxon King of England.[lower-alpha 1] Harold reigned Sweyn, Harold, Tostig, Gyrth, Leofwine and Wulfnoth. from 6 January 1066[1] until his death at the Battle of There were also three daughters: Edith of Wessex, origi- Hastings on 14 October, fighting the Norman invaders led nally named Gytha but renamed Ealdgyth (or Edith) when by William the Conqueror during the Norman conquest she married King Edward the Confessor; Gunhild; and of England. His death marked the end of Anglo-Saxon Ælfgifu. The birthdates of the children are unknown, but rule over England. Sweyn was the eldest and Harold was the second son.[9] Harold was aged about 25 in 1045, which makes his birth Harold was a powerful earl and member of a promi- [10] nent Anglo-Saxon family with ties to King Cnut. Upon date around 1020. the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066, the Witenagemot convened and chose Harold to succeed; he was crowned in Westminster Abbey. In late Septem- ber he successfully repelled an invasion by rival claimant 2 Powerful nobleman Harald Hardrada of Norway, before marching his army back south to meet William the Conqueror at Hastings Edith married Edward on 23 January 1045, and around some two weeks later. -

Was the Battle of Hastings Really Fought on Battle Hill? a GIS Assessment

Was the Battle of Hastings Really Fought on Battle Hill? A GIS Assessment Christopher Macdonald Hewitt Department of Geography University of Western Ontario ABSTRACT: Fought on a hillside in southern England in the fall of 1066, the Battle of Hastings has long been regarded as a seminal moment in British history, due to the profound changes the invading Norman conquerors brought to the British Isles. As such, the conflict has been the subject of significant historical analysis. One aspect of the battle that has not drawn much attention in academic accounts, however, relates to its location. To this point, observers have generally accepted that the site of the conflict was “Battle Hill,” pointing as evidence to the nearby presence of Battle Abbey, erected by the Norman leader, William the Conqueror, to commemorate his victory. Yet to this point, no archaeological evidence has been found to support the fact that a battle once occurred here. Furthermore, there are some local historians who believe that other sites are plausible. This study retests the case for Battle Hill as the site of the Battle of Hastings through a re-examination of historical data using a GIS-based multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) model. The results indicate that while Battle Hill is indeed a likely site for the conflict, another nearby location—Caulbec Hill is an equally if not more plausible contender. The study concludes by discussing the implications of this investigation for interdisciplinary research. Introduction he Battle of Hastings, fought on a hillside in southern England in the fall of 1066, has long been regarded as a seminal moment in British history. -

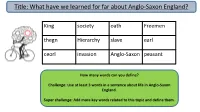

Title: What Have We Learned for Far About Anglo-Saxon England?

Title: What have we learned for far about Anglo-Saxon England? King society oath Freemen thegn Hierarchy slave earl ceorl invasion Anglo-Saxon peasant How many words can you define? Challenge: Use at least 3 words in a sentence about life in Anglo-Saxon England. Super challenge: Add more key words related to this topic and define them. Title: What have we learned for far about Anglo-Saxon England? Mutual respect How does life Individual Liberty Rule of law in Anglo- Tolerance Saxon Democracy England compare to today? Learning Objectives -Recap the structure of Anglo-Saxon society (towns, villages and churches). -Recap the events of the Norman Invasion of England. -Explain the main threats to William after the Norman Invasion in 1066. Anglo-Saxon knowledge check Contents: 1. Anglo-Saxon Society overview – true or false 2. The last years of Edward the Confessor – fill in the blanks 3. The Norman invasion and contenders to the throne- multiple choice quiz 4. Free recall- establishing control William! 5. RAG of your learning so far! Title: What have we learned for far about Anglo-Saxon England? Anglo-Saxon society was structured into a hierarchy of power. At the top of the hierarchy was the monarch (king). Underneath him, at the top of the hierarchy was the aristocracy. These were the people in society who were seen as being important because of their wealth ad power, which they have often inherited form their parents or ancestors. Learning Objectives -Recap the structure of Anglo-Saxon society (towns, villages and churches). -Recap the events of the Norman Invasion of England. -

Writing William. William the Conqueror and the Problem of Legitimacy In

Writing William William the Conqueror and the Problem of Legitimacy in Twelfth-Century English Historiography Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Pia Zachary aus München 2019 Erstgutachter: apl. Prof. Dr. Jörg Schwarz Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Claudia Märtl Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 7. Februar 2019 Acknowledgements This work is revised from my doctoral thesis submitted at the Ludwig-Maximilians- Universität that could not have been written in this form without the support of numer- ous people, for which I am very grateful. I wish to begin my thanks with my supervisor, Jörg Schwarz, for his constant support, feedback, and encouragement. The thesis was further examined by Claudia Märtl whom I want to thank for her feedback. Further, I want to thank Alessia Bauer for being part of the examination committee and for her constant encouragement. The fellow delegates of the conferences I attended encouraged me and lent me their advice. Thanks go especially to Emily Winkler and Alheydis Plassmann. Emily took her time to discuss my outline and shared her yet unpublished doctoral thesis. Alheydis Plassmann helped me sharpen my topic and introduced me to the Forschungsbereich England mit britischen Inseln im Mittelalter. I owe further thanks to Mark Hengerer and Martin Kaufhold for discussing my exposé with me. I further want to thank to my colleagues at the Writing Center who helped me improving my writing process and especially my English. Special thanks are to Sarah Martin and Mark Olival-Bartley for their patient proof-reading of all kind of texts, not least this one. -

The Strange Death of King Harold II: Propaganda and the Problem of Legitimacy in the Aftermath of the Battle of Hastings Chris Dennis

Feature The strange death of King Harold II: Propaganda and the problem of legitimacy in the aftermath of the Battle of Hastings Chris Dennis ow did King Harold II die at the oversight since it was undoubtedly the they cut Harold to pieces. The absence HBattle of Hastings? The question decisive moment in the battle: as the of the ‘hacking episode’ from the earliest is simple enough and the answer is conflict draws to a close, he notes, in Norman accounts and its subsequent apparently well known. Harold was passing, that Harold, his brothers and inclusion in the histories written in the killed by an arrow which struck him in many nobles had been killed. William early twelfth century is suggestive. It the eye. His death is depicted clearly on of Jumièges has Harold killed in the first is conceivable that the Norman court the Bayeux Tapestry in one of its most attack, ‘pierced with mortal wounds’.1 withheld it during William’s reign famous images: as the battle draws to Since he used the word ‘pierced’ some because his advisors were concerned a close, Harold stands underneath his might assume that he was intimating that the manner of Harold’s death would name in the inscription ‘Hic Harold rex that Harold had been struck by an have undermined the legitimacy of his interfectus est’, head tilted backwards, arrow; but his language is so imprecise own accession. clutching a golden arrow which that Frank Barlow has suggested that the But many historians do not endorse protrudes from his face. The scene is so phrase is nothing more than a literary this version of his death.