William the Conqueror and Wessex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix a PCC Protocol Death Senior National Figure.Pdf

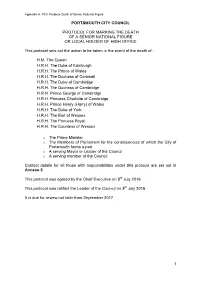

Appendix A: PCC Protocol Death of Senior National Figure PORTSMOUTH CITY COUNCIL PROTOCOL FOR MARKING THE DEATH OF A SENIOR NATIONAL FIGURE OR LOCAL HOLDER OF HIGH OFFICE This protocol sets out the action to be taken in the event of the death of: H.M. The Queen H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh H.R.H. The Prince of Wales H.R.H. The Duchess of Cornwall H.R.H. The Duke of Cambridge H.R.H. The Duchess of Cambridge H.R.H. Prince George of Cambridge H.R.H. Princess Charlotte of Cambridge H.R.H. Prince Henry (Harry) of Wales H.R.H. The Duke of York H.R.H. The Earl of Wessex H.R.H. The Princess Royal H.R.H. The Countess of Wessex o The Prime Minister o The Members of Parliament for the constituencies of which the City of Portsmouth forms a part o A serving Mayor or Leader of the Council o A serving member of the Council Contact details for all those with responsibilities under this protocol are set out in Annexe 5 This protocol was agreed by the Chief Executive on 8th July 2016 This protocol was ratified the Leader of the Council on 8th July 2016 It is due for review not later than September 2017 1 Appendix A: PCC Protocol Death of Senior National Figure PART 1 Implementation of the Protocol on hearing of the death Action required Authorised by Other Notes Portsmouth City Council’s Implementation will be The implementing officer mourning Protocol will be authorised by the Chief will arrange for flags to be implemented on the formal Executive or Assistant lowered immediately and announcement of the Chief Executive for books of condolence to be death of any one of those implementation by Claire opened on the next persons named on page 1 Looney, Partnership & working day. -

The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings The Battle of Hastings is one of the most famous battles in English history. What Caused the Battle? In 1066, three men were fighting to be King of England: William of Normandy, Harold Godwinson and Harald Hardrada. Harold Godwinson was crowned king on 6th January 1066. William and Harald were not happy. They both prepared to invade England in order to kill King Harold and become king themselves. Harald Hardrada attacked from the north of England on 25th September. However, he was killed in battle and his army was defeated by King Harold’s army. King Harold was then told that William of Normandy had landed in the south and was attacking the surrounding countryside. King Harold was furious and marched his tired troops 300 kilometres to meet them. Eight days later, Harold and his men reached London. William sent a messenger to London. The message tried to get Harold to accept William as the true King of England. Harold refused and was angered by William’s request. Harold was advised to wait before attacking William and his army. His troops were very tired and they needed time to prepare for the battle. However, Harold ignored this advice and on 13th October, his troops arrived in Hastings ready to fight. They captured a hill (now known as Battle Hill) and set up a fortress surrounded with sharp stakes stuck in a deep ditch. Harold ordered his forces to stay in their positions no matter what happened. The Battle of Hastings On 14th October, the battle began. -

The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975)

CARTER, JOHN MARSHALL. The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975). Directed by: Prof. John H. Beeler. The purpose of this study was to investigate the historical accounts of the Norman Conquest and its results. A select group of historians and works, primarily English, were investigated, beginning with the chronicles of medieval writers and continuing chronologically to the works of twentieth century historians. The majority of the texts that were examined pertained to the major problems of the Norman Conquest: the introduction of English feudalism, whether or not the Norman Conquest was an aristocratic revolution, and, how it affected the English church. However, other important areas such as the Conquest's effects on literature, language, economics, and architecture were observed through the "eyes" of past and present historians. A seconday purpose was to assemble for the student of English medieval history, and particularly the Norman Conquest, a variety of primary and secondary sources. Each new generation writes its own histories, seeking to add to the existing cache of material or to reinterpret the existing material in the light of the present. The future study of history will be significantly advanced by historiographic surveys of all major historical events. Professor Wallace K. Ferguson produced an indispensable work for students of the Italian Renaissance, tracing the development of historical thought from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. V Professor Bryce Lyon performed a similar task,if not on as epic a scale, with his essay on the diversity of thought in regard to the history of the origins of the Middle Ages. -

Erin and Alban

A READY REFERENCE SKETCH OF ERIN AND ALBAN WITH SOME ANNALS OF A BRANCH OF A WEST HIGHLAND FAMILY SARAH A. McCANDLESS CONTENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART I CHAPTER I PRE-HISTORIC PEOPLE OF BRITAIN 1. The Stone Age--Periods 2. The Bronze Age 3. The Iron Age 4. The Turanians 5. The Aryans and Branches 6. The Celto CHAPTER II FIRST HISTORICAL MENTION OF BRITAIN 1. Greeks 2. Phoenicians 3. Romans CHAPTER III COLONIZATION PE}RIODS OF ERIN, TRADITIONS 1. British 2. Irish: 1. Partholon 2. Nemhidh 3. Firbolg 4. Tuatha de Danan 5. Miledh 6. Creuthnigh 7. Physical CharacteriEtics of the Colonists 8. Period of Ollaimh Fodhla n ·'· Cadroc's Tradition 10. Pictish Tradition CHAPTER IV ERIN FROM THE 5TH TO 15TH CENTURY 1. 5th to 8th, Christianity-Results 2. 9th to 12th, Danish Invasions :0. 12th. Tribes and Families 4. 1169-1175, Anglo-Norman Conquest 5. Condition under Anglo-Norman Rule CHAPTER V LEGENDARY HISTORY OF ALBAN 1. Irish sources 2. Nemedians in Alban 3. Firbolg and Tuatha de Danan 4. Milesians in Alban 5. Creuthnigh in Alban 6. Two Landmarks 7. Three pagan kings of Erin in Alban II CONTENTS CHAPTER VI AUTHENTIC HISTORY BEGINS 1. Battle of Ocha, 478 A. D. 2. Dalaradia, 498 A. D. 3. Connection between Erin and Alban CHAPTER VII ROMAN CAMPAIGNS IN BRITAIN (55 B.C.-410 A.D.) 1. Caesar's Campaigns, 54-55 B.C. 2. Agricola's Campaigns, 78-86 A.D. 3. Hadrian's Campaigns, 120 A.D. 4. Severus' Campaigns, 208 A.D. 5. State of Britain During 150 Years after SeveTus 6. -

Captain Andrew Aspden the Private Secretary to the Earl of Wessex, Bagshot Park, Bagshot, Surrey, GU19 5PL

Captain Andrew Aspden The Private Secretary to the Earl of Wessex, Bagshot Park, Bagshot, Surrey, GU19 5PL 14th April 2021 Dear Earl of Wessex, I was deeply saddened to learn of the death of His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and I join with the nation in mourning his loss. I write to express my deepest sympathy to you and The Countess of Wessex. On behalf of the Rayner farming family of Royal Berkshire, the whole family gives thanks for His Royal Highness’ dedicated service to the nation, and commitment to making a difference via so many charitable causes. His Royal Highness’ constant support to her Majesty throughout seven decades of marriage has been a true inspiration. I was extremely privileged that His Royal Highness was able to attend my Mayor’s ball in May 2013 at Guards Polo Club. His Royal Highness made it an incredibly special evening, as he took time to speak to the three school choirs, including the choir from St Mary’s School Ascot, and all our guests. With His Royal Highness The Prince Philip’s help, we raised a lot of money for The Prince Philip Trust Fund that night. His Royal Highness offered great support and wise words while my team was building the Carriage Driving Courses in the grounds of Windsor Castle. We will miss seeing His Royal Highness driving in his carriages and Land Rover around Home Park Private while we are preparing for the Royal Windsor Horse Show. I have many fond memories and encounters to remember His Royal Highness Prince Philip by. -

9769 SP5A.Indd

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge Pre-U Certifi cate HISTORY (PRINCIPAL) 9769/05A Paper 5A Special Subject: The Norman Conquest, 1051–1087 For Examination from 2016 SPECIMEN PAPER 2 hours Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *0123456789* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, glue or correction fl uid. DO NOT WRITE IN ANY BARCODES. Answer Question 1 in Section A Answer one question from Section B. You are reminded of the need for analysis and critical evaluation in your answers to questions. You should also show, where appropriate, an awareness of links and comparisons between different countries and different periods. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. The syllabus is approved for use in England, Wales and Northern Ireland as a Cambridge International Level 3 Pre-U Certifi cate. This document consists of 3 printed pages and 1 blank page. © UCLES 2014 [Turn over 2 Section A Nominated topic: The Invasion of 1066 1 Study all the following documents and answer the questions which follow. In evaluating and commenting on the documents, it is essential to set them alongside, and to make use of, your own contextual knowledge. A An English chronicler, probably writing in Worcester, gives an account of King Harold’s campaigns in 1066. -

The Bishop of Winchester's Deer Parks in Hampshire, 1200-1400

Proc. Hampsk. Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 44, 1988, 67-86 THE BISHOP OF WINCHESTER'S DEER PARKS IN HAMPSHIRE, 1200-1400 By EDWARD ROBERTS ABSTRACT he had the right to hunt deer. Whereas parks were relatively small and enclosed by a park The medieval bishops of Winchester held the richest see in pale, chases were large, unfenced hunting England which, by the thirteenth century, comprised over fifty grounds which were typically the preserve of manors and boroughs scattered across six southern counties lay magnates or great ecclesiastics. In Hamp- (Swift 1930, ix,126; Moorman 1945, 169; Titow 1972, shire the bishop held chases at Hambledon, 38). The abundant income from his possessions allowed the Bishop's Waltham, Highclere and Crondall bishop to live on an aristocratic scale, enjoying luxuries (Cantor 1982, 56; Shore 1908-11, 261-7; appropriate to the highest nobility. Notable among these Deedes 1924, 717; Thompson 1975, 26). He luxuries were the bishop's deer parks, providing venison for also enjoyed the right of free warren, which great episcopal feasts and sport for royal and noble huntsmen. usually entitled a lord or his servants to hunt More deer parks belonged to Winchester than to any other see in the country. Indeed, only the Duchy of Lancaster and the small game over an entire manor, but it is clear Crown held more (Cantor et al 1979, 78). that the bishop's men were accustomed to The development and management of these parks were hunt deer in his free warrens. For example, recorded in the bishopric pipe rolls of which 150 survive from between 1246 and 1248 they hunted red deer the period between 1208-9 and 1399-1400 (Beveridge in the warrens of Marwell and Bishop's Sutton 1929). -

Philip De Sayton's Grandfather Fought with William the Conqueror At

Philip de Sayton’s grandfather fought with William the Conqueror at Hastings in 1066. Winton was built by the Setons following a grant of land by David I to Phillip de Sayton in 1150. Phillip’s grandson married the sister of King Robert “The Bruce” of Scotland. In the sixteenth century, Henry VIII had Winton burnt in an effort to impress Mary Queen of Scots, and Mary Seton was later her Lady-in-Waiting. The Seton’s tenure lasted until 1715 when they backed the Jacobites and the Earl of Winton was taken to the Tower of London. The Earl’s capture ended an era when Kings were entertained and master craftsmen were engaged fresh from Edinburgh Castle to embellish Winton House in the style of the Scottish Renaissance. In the absence of the Earl but in his name, Winton was requisitioned by Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745 when his rebel army camped on Winton Estate. The Hamilton Nisbets, who bought the House and Estate, linked it to one of the greatest inheritances of the 18th and 19th centuries. The furnishings came from all over Europe and the Turkish Empire and the impressive estates covered some of the country's best farmland. Golf was not just a pastime but was carried out on estate land, which, at that time, included Muirfield and Gullane Links. For over a century, Winton has hosted musical evenings and private functions; more recently it has successfully been used for corporate dinners and lunches, conferences, product launches and weddings, using the main rooms of the House. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the Family, the Fief and the Feudal Monarchy*

© K.S.B. Keats-Rohan 1991. Published Nottingham Mediaeval Studies 36 (1992), 42-78 The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the family, the fief and the feudal monarchy* In memoriam R.H.C.Davis 1. The Problem (i) the non-Norman Conquest Of all the available studies of the Norman Conquest none has been more than tangentially concerned with the fact, acknowledged by all, that the regional origin of those who participated in or benefited from that conquest was not exclusively Norman. The non-Norman element has generally been regarded as too small to warrant more than isolated comment. No more than a handful of Angevins and Poitevins remained to hold land in England from the new English king; only slightly greater was the number of Flemish mercenaries, while the presence of Germans and Danes can be counted in ones and twos. More striking is the existence of the fief of the count of Boulogne in eastern England. But it is the size of the Breton contingent that is generally agreed to be the most significant. Stenton devoted several illuminating pages of his English Feudalism to the Bretons, suggesting for them an importance which he was uncertain how to define.1 To be sure, isolated studies of these minority groups have appeared, such as that of George Beech on the Poitevins, or those of J.H.Round and more recently Michael Jones on the Bretons.2 But, invaluable as such studies undoubtedly are, they tend to achieve no more for their subjects than the status of feudal curiosities, because they detach their subjects from the wider question of just what was the nature of the post-1066 ruling class of which they formed an integral part. -

1966 – 900Th Anniversary of the Battle of Hastings

SPECIAL STAMP HISTORY 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings 1966 The story of the stamps to mark the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings began with a letter of 5 November 1962 to the Postmaster General (PMG) from the ‘1966 Celebrations Council’, constituted in Hastings to prepare events to celebrate the anniversary. The letter suggested that ‘this famous anniversary in the history of our country’ be commemorated by stamps. The reply from the GPO, dated 9 November, was non-committal. The Council was informed that the policy regarding special stamps confined them to ‘outstanding current national or international events and Royal and postal anniversaries’. Even though the Battle of Hastings resulted in the death of the last Saxon King of England and marked the beginning of the Norman Monarchy, the 900th anniversary was clearly seen by the GPO as an historical, rather than royal, anniversary. Such anniversaries were excluded by the policy unless of outstanding historical importance and marked by notable current events. The GPO therefore asked to be kept informed of the events the Council proposed to stage, in order to decide whether this occasion warranted an issue of stamps. Planning of the anniversary celebrations was in its infancy and the Council had only undeveloped ideas. These included re-enacting King Harold’s march from Stamford Bridge and the Battle of Hastings itself. The feeling within the GPO was that the planned celebrations ‘had the air of a local publicity drive’ and, as such, did not merit an issue of stamps. On 14 November 1962, Captain H Kerby asked in Parliament whether the PMG intended to issue stamps to commemorate the 900th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings. -

British Royal Ancestry Book 6, Kings of England from King Alfred the Great to Present Time

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY BRITISH ROYAL ANCESTRY, BOOK 6 Kings of England INTRODUCTION The British ancestry is very much a patchwork of various beginnings. Until King Alfred the Great established England various Kings ruled separate parts. In most cases the initial ruler came from the mainland. That time of the history is shrouded in myths, which turn into legends and subsequent into history. Alfred the Great (849-901) was a very learned man and studied all available past history and especially biblical information. He came up with the concept that he was the 72nd generation descendant of Adam and Eve. Moreover he was a 17th generation descendant of Woden (Odin). Proponents of one theory claim that he was the descendant of Noah’s son Sem (Shem) because he claimed to descend from Sceaf, a marooned man who came to Britain on a boat after a flood. (See the Biblical Ancestry and Early Mythology Ancestry books). The book British Mythical Royal Ancestry from King Brutus shows the mythical kings including Shakespeare’s King Lair. The lineages are from a common ancestor, Priam King of Troy. His one daughter Troana leads to us via Sceaf, the descendants from his other daughter Creusa lead to the British linage. No attempt has been made to connect these rulers with the historical ones. Before Alfred the Great formed a unified England several Royal Houses ruled the various parts. Not all of them have any clear lineages to the present times, i.e. our ancestors, but some do. I have collected information which shows these. They include; British Royal Ancestry Book 1, Legendary Kings from Brutus of Troy to including King Leir.