The Strange Death of King Harold II: Propaganda and the Problem of Legitimacy in the Aftermath of the Battle of Hastings Chris Dennis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux and Earl of Kent

( 55 ) ODO, BISHOP OF BAYEUX AND EARL OF KENT. BY SER REGINALD TOWER, K.C.M.G., C.Y.O. IN the volumes of Archceologia Cantiana there occur numerous references to Bishop Odo, half-brother of William the Conqueror ; and his name finds frequent mention in Hasted's History of Kent, chiefly in connection with the lands he possessed. Further, throughout the records of the early Norman chroniclers, the Bishop of Bayeux is constantly cited among the outstanding figures in the reigns of William the Conqueror and of his successor William Rufus, as well as in the Duchy of Normandy. It seems therefore strange that there should be (as I am given to understand) no Life of the Bishop beyond the article in the Dictionary of National Biography. In the following notes I have attempted to collate available data from contemporary writers, aided by later historians of the period during, and subsequent to, the Norman Conquest. Odo of Bayeux was the son of Herluin of Conteville and Herleva (Arlette), daughter of Eulbert the tanner of Falaise. Herleva had .previously given birth to William the Conqueror by Duke Robert of Normandy. Odo's younger brother was Robert, Earl of Morton (Mortain). Odo was born about 1036, and brought up at the Court of Normandy. In early youth, about 1049, when he was attending the Council of Rheims, his half-brother, William, bestowed on him the Bishopric of Bayeux. He was present, in 1066, at the Conference summoned at Lillebonne, by Duke William after receipt of the news of Harold's succession to the throne of England. -

Anglo- Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066

1.1 Anglo- Saxon society Key topic 1: Anglo- Saxon England and 1.2 The last years of Edward the Confessor and the succession crisis the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066 1.3 The rival claimants for the throne 1.4 The Norman invasion The first key topic is focused on the final years of Anglo-Saxon England, covering its political, social and economic make-up, as well as the dramatic events of 1066. While the popular view is often of a barbarous Dark-Ages kingdom, students should recognise that in reality Anglo-Saxon England was prosperous and well governed. They should understand that society was characterised by a hierarchical system of government and they should appreciate the influence of the Church. They should also be aware that while Edward the Confessor was pious and respected, real power in the 1060s lay with the Godwin family and in particular Earl Harold of Wessex. Students should understand events leading up to the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066: Harold Godwinson’s succession as Earl of Wessex on his father’s death in 1053 inheriting the richest earldom in England; his embassy to Normandy and the claims of disputed Norman sources that he pledged allegiance to Duke William; his exiling of his brother Tostig, removing a rival to the throne. Harold’s powerful rival claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Hardrada and Edgar – and their motives should also be covered. Students should understand the range of causes of Harold’s eventual defeat, including the superior generalship of his opponent, Duke William of Normandy, the respective quality of the two armies and Harold’s own mistakes. -

The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings The Battle of Hastings is one of the most famous battles in English history. What Caused the Battle? In 1066, three men were fighting to be King of England: William of Normandy, Harold Godwinson and Harald Hardrada. Harold Godwinson was crowned king on 6th January 1066. William and Harald were not happy. They both prepared to invade England in order to kill King Harold and become king themselves. Harald Hardrada attacked from the north of England on 25th September. However, he was killed in battle and his army was defeated by King Harold’s army. King Harold was then told that William of Normandy had landed in the south and was attacking the surrounding countryside. King Harold was furious and marched his tired troops 300 kilometres to meet them. Eight days later, Harold and his men reached London. William sent a messenger to London. The message tried to get Harold to accept William as the true King of England. Harold refused and was angered by William’s request. Harold was advised to wait before attacking William and his army. His troops were very tired and they needed time to prepare for the battle. However, Harold ignored this advice and on 13th October, his troops arrived in Hastings ready to fight. They captured a hill (now known as Battle Hill) and set up a fortress surrounded with sharp stakes stuck in a deep ditch. Harold ordered his forces to stay in their positions no matter what happened. The Battle of Hastings On 14th October, the battle began. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975)

CARTER, JOHN MARSHALL. The Norman Conquest: Ten Centuries of Interpretation (1975). Directed by: Prof. John H. Beeler. The purpose of this study was to investigate the historical accounts of the Norman Conquest and its results. A select group of historians and works, primarily English, were investigated, beginning with the chronicles of medieval writers and continuing chronologically to the works of twentieth century historians. The majority of the texts that were examined pertained to the major problems of the Norman Conquest: the introduction of English feudalism, whether or not the Norman Conquest was an aristocratic revolution, and, how it affected the English church. However, other important areas such as the Conquest's effects on literature, language, economics, and architecture were observed through the "eyes" of past and present historians. A seconday purpose was to assemble for the student of English medieval history, and particularly the Norman Conquest, a variety of primary and secondary sources. Each new generation writes its own histories, seeking to add to the existing cache of material or to reinterpret the existing material in the light of the present. The future study of history will be significantly advanced by historiographic surveys of all major historical events. Professor Wallace K. Ferguson produced an indispensable work for students of the Italian Renaissance, tracing the development of historical thought from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. V Professor Bryce Lyon performed a similar task,if not on as epic a scale, with his essay on the diversity of thought in regard to the history of the origins of the Middle Ages. -

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20040245547A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2004/0245547 A1 Stipe (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 9, 2004 (54) ULTRA LOW-COST SOLID-STATE MEMORY Publication Classi?cation (75) Inventor; Barry Cushing Stipe, San Jose, CA (51) Int. Cl.7 ................................................ .. H01L 31/109 (Us) (52) US. Cl. ............................................................ .. 257/200 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT JOSEPH P. CURTIN . A three-dimensional solid-state memory is formed from a plurality of bit lines, a plurality of layers, a plurality of tree ’ structures and a plurality of plate lines. Bit lines extend in a (73) A551 nee, Hitachi Global Stora e Technolo ies ?rst direction in a ?rst plane. Each layer includes an array of g ' B V AZ Amsterdam g memory cells, such as ferroelectric or hysteretic-resistor ' " memory cells. Each tree structure corresponds to a bit line, (21) APPL NO: 10/751 740 has a trunk portion and at least one branch portion. The trunk ’ portion of each tree structure extends from a corresponding (22) Filed; Jam 5, 2004 bit line, and each tree structure corresponds to a plurality of layers. Each branch portion corresponds to at least one layer Related US, Application Data and extends from the trunk portion of a tree structure. Plate lines correspond to at least one layer and overlap the branch (63) Continuation-in-part of application No. 10/453,137, portion of each tree structure in at least one roW of tree ?led on Jun. 3, 2003, noW abandoned. structures at a plurality of intersection regions. SRIIIIII DRAM HIIIJ FLASH PROBE GUM MTJ-MRAM 3D-MHAM MATRIX ITFBRIIM GT FERAM 001 size 50F? 012 512 502 502 5F? 002 5e? 512 002 502 Minimum "1" 100m 300m 100m 30 0m 311m 100m 40 nm 400m 10 nm 100m 100m MEX. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor. -

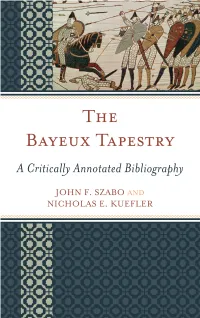

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

9769 SP5A.Indd

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge Pre-U Certifi cate HISTORY (PRINCIPAL) 9769/05A Paper 5A Special Subject: The Norman Conquest, 1051–1087 For Examination from 2016 SPECIMEN PAPER 2 hours Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *0123456789* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, glue or correction fl uid. DO NOT WRITE IN ANY BARCODES. Answer Question 1 in Section A Answer one question from Section B. You are reminded of the need for analysis and critical evaluation in your answers to questions. You should also show, where appropriate, an awareness of links and comparisons between different countries and different periods. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. The syllabus is approved for use in England, Wales and Northern Ireland as a Cambridge International Level 3 Pre-U Certifi cate. This document consists of 3 printed pages and 1 blank page. © UCLES 2014 [Turn over 2 Section A Nominated topic: The Invasion of 1066 1 Study all the following documents and answer the questions which follow. In evaluating and commenting on the documents, it is essential to set them alongside, and to make use of, your own contextual knowledge. A An English chronicler, probably writing in Worcester, gives an account of King Harold’s campaigns in 1066. -

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France

The Idea of Medieval Heresy in Early Modern France Bethany Hume PhD University of York History September 2019 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the historiographical focus on the trope of the Albigensians and Waldensians within sixteenth-century confessional polemic. It supports a shift away from the consideration of medieval heresy in early modern historical writing merely as literary topoi of the French Wars of Religion. Instead, it argues for a more detailed examination of the medieval heretical and inquisitorial sources used within seventeenth-century French intellectual culture and religious polemic. It does this by examining the context of the Doat Commission (1663-1670), which transcribed a collection of inquisition registers from Languedoc, 1235-44. Jean de Doat (c.1600-1683), President of the Chambre des Comptes of the parlement of Pau from 1646, was charged by royal commission to the south of France to copy documents of interest to the Crown. This thesis aims to explore the Doat Commission within the wider context of ideas on medieval heresy in seventeenth-century France. The periodization “medieval” is extremely broad and incorporates many forms of heresy throughout Europe. As such, the scope of this thesis surveys how thirteenth-century heretics, namely the Albigensians and Waldensians, were portrayed in historical narrative in the 1600s. The field of study that this thesis hopes to contribute to includes the growth of historical interest in medieval heresy and its repression, and the search for original sources by seventeenth-century savants. By exploring the ideas of medieval heresy espoused by different intellectual networks it becomes clear that early modern European thought on medieval heresy informed antiquarianism, historical writing, and ideas of justice and persecution, as well as shaping confessional identity.