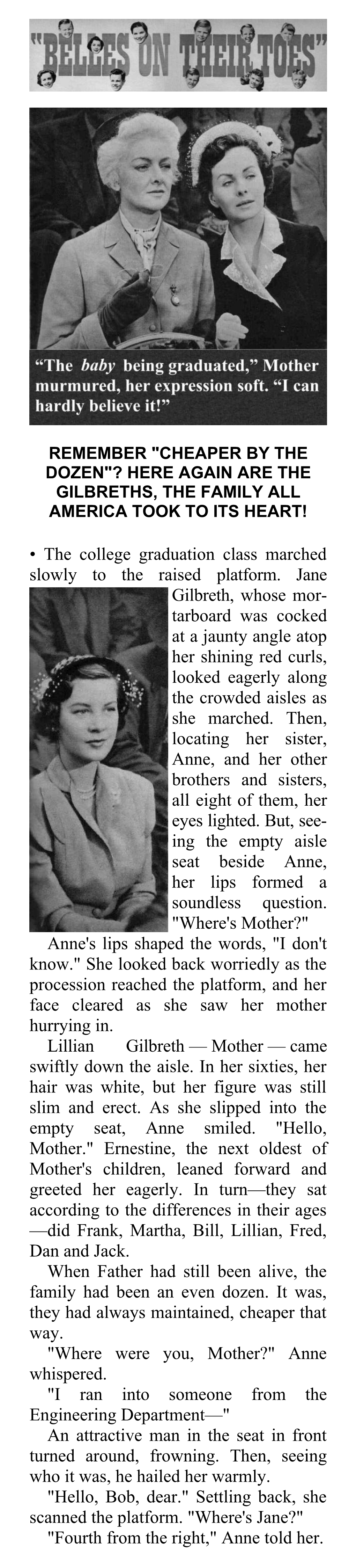

Belles on Their Toes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillian Moller Gilbreth Biografia

Resumen sobre Lillian Moller Gilbreth Lillian Evelyn (Möller) Gilbreth (Oakland, 1878-Phoenix, 1972) ingeniera, psicóloga, profesora y madre de familia numerosa es, fundamentalmente, la madre de la moderna gestión empresarial. Ella y su marido Frank Bunker Gilbreth (1868- 1924) fueron los pioneros en algunas técnicas de gestión empresarial que aún se emplean actualmente en la construcción y en otras industrias. Lillian fue además una de esas primeras supermujeres, capaces de combinar una carrera brillante con una vida familiar clásica: fue una prolifica autora, obtuvo diferentes licenciaturas y fue la madre de doce hijos. Quizás encontremos a veces que es mejor recordada por su maternidad, ya que dos de sus hijos, Frank Gilbreth Jr. y Ernestine Gilbreth Carey, escribieron los populares libros Cheaper by the Dozen (1949) en y Belles on Their Toes (1950), que fueron llevados a la gran pantalla en más de una ocasión, y en los que cuentan sus experiencias en el seno de una familia grande y famosa, aunque Lillian Gilberth no solamente fue madre de familia. La joven Lillian Evelyn Möller fue una alumna destacada en el instituto y decidió en principio estudiar música y literatura, aunque su padre no veía por ningún lado la necesidad de que una mujer accediese a una enseñanza superior, siendo de los que pensaban que le bastaban los conocimientos que le sirviesen para llevar una casa eficazmente. Pero Lillian le convenció para que la dejara asistir a clase en la Universidad de California, en Berkeley mientras viviera en casa y atendiera las tareas domésticas, y ya que estudiaba allí un primo suyo. -

That Most Famous Dozen

That Most Famous Dozen By DAVID FERGUSON Introduction In the movie, Belles on Their Toes, the last scene depicts Lillian Gilbreth (and Frank looking on from heaven), watching as the last of the Gilbreth Dozen graduates from college, thus ending the film story of this family. While the books, starting with Cheaper by the Dozen, and movies all came out within the same few short years at the middle of the century, the 1925: Lillian with all the children except Anne public certainly has not forgotten the Gilbreth family. Since forming The Gilbreth Network, the most frequently asked questions concern the Gilbreth "children." Where are they now? What did they do for a living? Did any of them have large families? After the web site was created, the requests for information increased to the point where, if I sold this story, I could have retired on the sales. I want to express my thanks to Ernestine Gilbreth Carey, for supplying much of the in- formation contained herein. We discussed this article and had to weigh your interest against the family's desire for privacy. If we could say one thing about the Gilbreth family, it is that they're no different than any of us, in that they like their privacy. After all, we all get too many calls, ask- ing us to switch long-distance phone carriers, without adding to the problem. The Gilbreth Dozen The children of Frank B. Gilbreth and Lillian M. Gilbreth were born between 1905 and 1922. While their father died at the early age of 55 (a month shy of his 56th birthday), his children, for the most part, took after their mother, as far as longevity is concerned. -

^ QUALITY... Removed in a Routine Procedure, Weinberg Said

80 MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday, Sept. 8, 1989 CARS CARS CARS CARS Remove mineral buildup I [CARS from your feokettle by FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE I CARS CARS FOR SALE FOR SALE FOR SALE pouring In holt o cup of white ylnegor and one BUICK Electra Estate PONTIAC Flero 1985 - FORD LTD Country PLYMOUTH Renault SUBARU Brot 1979 . quart of top wafer. Heat to Wagon 1982 - Good Saulre Wagon - 1972, CHEVY Camaro Z-281985 PONTIAC Firebird 1977 - Automatic, V-6, low 1982 - All options, 81K. B®stofter.643- rolling boll and let stand condition. S2900. 646- 400V-8, excellent condi Excellent condition. 1 - T-top, power steerlng- Needs work. Best otter. mileage, silver with 2005, leave message. 4526. Coll 649-9151 otter 5pm. for one hour. Pour out block spoiler, mags, tion. $500. 647-7890. owner, $1,950 or best /brakes, V-8,5.0L,47K, solution, till with water, offer. 647-0347. CHEVROLET 1984 Celeb- $5,900. 646-9826. CHEVROLET Comoro a/c, om/fm cassette, rltv - 4 door, fully boll again and discord. tilt wheel, tinted win AUDI 40uu 1980 - $2500 1985 - V-6, tuned port Add buildup to your dows. $5,495 or best equipped. Excellent Excellent condition Infection, 5 speed olr, condition. Asking budget by selling no- offer. 742-1398 plus extras. 646-9826. power steering and longer used furniture and evenings. $4,000. 646-2392. brokes, om/fm, 82K, $4,499. 646-9826. appliances with a low-cost CLYbE od In Classified. 643-2711. CHEVROLET-BUICK, INC. ROUTE 83, VERNON CARDINAL BUICK'S VOLUME 84 Cutlata Coups *5895 ^4 Buick Csntury Wag *5995 85 Reliant 4 Door *4995 85 Buick Elsctra 4 Or. -

Ebook \\ Belles on Their Toes > Read

ZIFTSLHDVE # Belles on Their Toes // Book Belles on Th eir Toes By Frank B Gilbreth, Ernestine Gilbreth Carey HarperCollins, United States, 2003. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Perennial.. 202 x 130 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. Life is very different now in the rambling Gilbreth house.When the youngest was two and the oldest eighteen, Dad died and Mother bravely took over his business. Now, to keep the family together, everyone has to pitch in and pinch pennies. The resourceful clan rises to every crisis with a marvelous sense of fun -- whether it s battling chicken pox, giving the boot to an unwelcome boyfriend, or even meeting the President. And the few distasteful things they can t overcome -- like castor oil -- they swallow with good humor and good grace. Belles on Their Toes is a warm, wonderful, and entertaining sequel to Cheaper by the Dozen. READ ONLINE [ 8.05 MB ] Reviews Completely essential read publication. It is really basic but excitement in the fiy percent of the book. You will not really feel monotony at anytime of your respective time (that's what catalogues are for about in the event you ask me). -- Lexie Paucek PhD This book is indeed gripping and fascinating. It normally is not going to price a lot of. I am very easily will get a delight of reading a created pdf. -- Albertha Cartwright UDFLALZCGL \ Belles on Their Toes « eBook Related Books 101 Ways to Beat Boredom: NF Brown B/3b Pearson Education Limited. Paperback. Book Condition: new. BRAND NEW, 101 Ways to Beat Boredom: NF Brown B/3b, Anna Claybourne, This title is part of Bug Club, the first whole-school reading programme to combine books with an online reading world to teach today's.. -

Nasty Women Transgressive Womanhood in American History

Nasty Women Transgressive Womanhood in American History Edited by Marian Mollin With the Students of HIST 4914 - Spring 2020 The saying goes that well-behaved women rarely make history. For centuries, American women have been carving out spaces of their own in a male-dominated world. From politics, to entertainment, to their personal lives, women have been making their mark on the American landscape since the nation’s inception, often ignored or overlooked by those creating the record. This collection takes the long view of the American woman and examines her transgressive behavior through the decades. Including stories of women enslaved, early celebrities, engineers, and more, these essays demonstrate how there is no such thing as an “average” woman, as even those ordinary women are found doing extraordinary things. This collection comes at a particularly poignant time, as August 2020 marked the 100th anniversary of the ratification and adoption of the 19th amendment, which – in a landmark for women’s right – granted American women the right to vote. Virginia Tech Department of History in association with ISBN 9781949373516 90000 > 9 781949 373516 Nasty Women Nasty Women: Transgressive Womanhood in American History is part of the Virginia Tech Student Publications series. This series contains book-length works authored and edited by Virginia Tech undergraduate and graduate students and published in collaboration with Virginia Tech Publishing. Often these books are the culmination of class projects for advanced or capstone courses. The series provides the opportunity for students to write, edit, and ultimately publish their own books for the world to learn from and enjoy. -

Myrna Loy ~ 46 Films and More

Myrna Loy ~ 46 Films and more Myrna Loy was born Myrna Adele Williams on 2 August 1905 in Radersburg, Montana to parents of Welsh, Scottish and Swedish descent. After her rancher father David became, at just 21, the youngest man ever elected to the Montana State Legislature, the family moved 35 miles to Helena, the state capital, which is where Myrna grew up. Frank (later Gary) Cooper, four years her senior, was a near neighbour: We lived high off the hog on Fifth Avenue. It was just a nice middle- class neighbourhood. Most of the richer families were building on the opposite mountainside. Helena is a spacious city, climbing up Mount Ascension and Mount Helena from Last Chance Gulch, so we had wonderful, steep streets. When it snowed you could slide past Judge Cooper's house all the way to the railroad station in the valley part of town. The Coopers lived just below us in a fairly elegant house with an iron fence around it.1 In 1918 a flu pandemic swept the world, and one of its countless victims was 39 year old David Williams. This prompted his widow Ella to move with children Myrna and nine year old David to Los Angeles. There Myrna attended the Westlake School for Girls where at the age of 15 she caught the acting bug. In 1924-5, she came to the attention of silver screen big-hitters Rudolph and Natacha Valentino, following which doors of opportunity began to open. Her first film, released in 1925, was What Price Beauty? Later the same year she appeared alongside young Joan Crawford in Pretty Ladies. -

Belles on Their Toes Free

FREE BELLES ON THEIR TOES PDF Frank B Gilbreth,Ernestine Gilbreth Carey | 240 pages | 16 Dec 2003 | HarperCollins | 9780060598235 | English | New York, NY, United States Belles on Their Toes - Wikipedia Looking at this character, it was difficult to believe that she had a dozen children. She was slim, tall, and beautiful and had red hair. She worked closely with her husband in the field of engineering even though this was highly unusual for a woman in the early s. After his death, she traveled to Europe to give lectures and to try to persuade her husband's clients to remain with her so that her family could stay together. Even though she was very busy with her work, her children were her priority. Somehow she always came up with the time to become an integral part of their lives. This character was very resourceful and economical. She didn't worry about details that she felt others could handle, and she included her children and their opinions in her decisions. She Belles on Their Toes so close to their children. Browse all BookRags Study Guides. All rights reserved. Toggle navigation. Sign Up. Sign In. Get Belles on Their Toes from Amazon. View the Study Pack. Plot Summary. Belles on Their Toes Chapters 16 - Topics for Discussion. Print Word PDF. This section contains words approx. Lillian Gilbreth Looking at this character, it was difficult to believe that she had Belles on Their Toes dozen children. She was so close to their children Tom This was View a FREE sample. More summaries and resources for teaching or studying Belles on Their Toes. -

Printer Friendly Version

Printer Friendly Version http://omaha.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100118/ENTERTAIN... Published Jan 18, 2010 Published Monday January 18, 2010 Curtain to rise on family's story By Bob Fischbach WORLD-HERALD STAFF WRITER PURDUE LIBRARIES' ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS Frank and Lillian Gilbreth with 11 of their 12 children sometime in the 1920s. When “Cheaper by the Dozen” opens Friday night at the Omaha Community Playhouse, three generations of an Omaha family will be excited to be there. That's their family's story being told onstage. “Cheaper by the Dozen,” a book about the life of a family with 12 children, became a best seller in 1948. A hit movie version, starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy as parents Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, followed in 1950. The Gilbreths were industrial engineers, efficiency experts who studied repetitive motion. The movie finds humor in the efficient way Frank ran his home and his large family. Irene Gilbreth, 91, widow of Frank and Lillian's son Dan, will be at the playhouse Friday, along with her daughter, Peggy Nipper, 68, and grandson, Zach Nipper, 35. A fourth generation, great-granddaughter, Claire Nipper, 3, is too young to attend. Though the family home, as the book records, is in Montclair, N.J., Peggy is the reason for the Omaha branch. Her husband, Henry, is an associate professor of pathology and assistant dean for admissions for Creighton University's medical school. They moved here in 1986. When Peggy's mother got older, she moved from the East Coast to Omaha to be near her daughter. -

Gender and the Screenplay Processes, Practices, Perspectives

Networking Knowledge_________ Volume 10 Issue 2 June 2017 Gender and the Screenplay Processes, Practices, Perspectives Guest Edited by Louise Sawtell and Stayci Taylor Networking Knowledge Gender and the Screenplay (Jun. 2017) Networking Knowledge Special Issue Gender and the Screenplay: Processes, Practices, Perspectives Edited by Louise Sawtell and Stayci Taylor TABLE OF CONTENTS Gender and the Screenplay: Processes, Practices, Perspectives. An Introduction. Louise Sawtell and Stayci Taylor 1 Hidden a-Gender?: questions of gender in screenwriting practice Stayci Taylor 4 An Interview with Helen Jacey Interviewed by Louise Sawtell and Stayci Taylor 14 In her own voice: Reflections on the Irish film industry and beyond Susan Liddy 19 Re-Configuring the New Women – Female Screenwriters and Street Films in Weimar Republic Juliane Scholz 32 Bracketting Noir: Narrative and Masculinity in The Long Goodbye Kyle Barrett 43 Position-in-frame: gendered mobility, legacy and transformative sacrifice in the screen stories of Susanne Bier Cath Moore 54 Honey, You Know I Can’t Hear You When You Aren’t in the Room: Key Female Filmmakers Prove the Importance of Having a Female in the Writing Room Rosanne Welch 67 Sexism From Page to Screen: How Hollywood Screenplays Inscribe Gender Radha O’Meara 77 i Networking Knowledge Editorial (Jun. 2017) Gender and the Screenplay: Processes, Practices, Perspectives. An Introduction. LOUISE SAWTELL AND STAYCI TAYLOR, RMIT University While plenty has been written about gender representation on screen, much less has been written about gender in regards to screenplays. Emerging scholarly research around screenwriting practice often focuses on questions of the craft – is screenwriting a technical or creative act? – and whether or not the screenplay’s only destiny is to disappear into the film (Carriére, cited in Maras 1999, 147). -

Teacher's Guide

TEACHER’S GUIDE TUNDRA BOOKS 1 www.tundrabooks.com @TundraBooks facebook.com/TundraBooks DEAR EDUCATOR Spic-and-Span! Lillian Gilbreth’s Wonder Kitchen presents the life of the highly intelligent, enormously creative and accom- plished Lillian Gilbreth. An efficiency expert, an industrial engineer, an inventor, a psychologist, an author and a professor, Gilbreth was the first woman elected to the National Academy of Engineering, was the subject of two movies and had a U.S. postage stamp issued in her honor. Spic-and-Span! can be used in the classroom in a number of ways including: • Exploring conceptual and thematic connections such as function, change, connection, efficiency, convenience, time, innovation, progress and feminism • As an introduction to the genre of biography • Enrichment for a science and technology unit • As a whole class read aloud or for independent reading and/or research The activity guide includes a variety of discussion questions, whole class, small group, and independent activities and prompts to elicit a meaningful understanding of the text for children ranging in age from five to eight years. The suggested activities can be adapted to suit the needs of your students. Where applicable, activities have been aligned with Common Core State Stan- dards. ABOUT THE BOOK Lillian Moller Gilbreth, born in 1878, put her privileged life aside for one of adventure and challenge. She and her husband, Frank, became efficiency experts by studying the actions of factory workers. They ran their household of eleven children ef- ficiently too. When Frank suddenly died, Lillian faced enormous worry. Where would the family live? How would she pay for their food, clothing and education? When the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company eventually hired her to improve kitchen design, Lillian interviewed over four thousand women to discover what didn’t work in their own kitchens. -

Management, Chester Barnard, Frank and Gilberth Theory, Gantt Contribution

Items Description of Module Subject Name Human Resource Management Paper Name Development of Management Thoughts, Principles and Types Module Title Early Contributors Module Id Module No. -5 Pre- Requisites Concept of Management Objectives To understand the different schools of thoughts Keywords Management, Chester Barnard, Frank and Gilberth Theory, Gantt Contribution QUADRANT-I Module 5: Early Contributors 5.1 Learning Objective 5.2 Introduction 5.3 Chester Barnard contribution to Management Thoughts 5.4 Formal and Informal Organisations 5.5 Frank and Lillian Gilberth Theory .6 Gantt Contribution 5.7 Perspectives 5.8 Summary 5.1 Learning Objectives After completing this module, you will be able to: Objective: 1. To understand the great classical theories of management. 2. To enable a sense of humour about the beginning of the contributors towards management practices. 3. To build a relationship between early management thoughts and modern thought of control. Introduction The early contributors include Chester Barnard who studied organization in systematic way and defined organizations in two types. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth who are considered the founders of modern industrial management, who sought to improve workers' productivity while making their work easier. Gantt's contribution who is often seen as a disciple of Taylor and a promoter of the scientific school of management. In his early career, with the influence of Taylor - and Gantt's aptitude for problem-solving - resulted in attempts to address the technical problems of scientific management. In this module we will learn in detail their contributions in management. Chester Barnard Chester Barnard was the President of new Jerray Bell Telephone Company. -

Yaszek Final.Indb

GALACTIC SUBURBIA YYaszekaszek ffinal.indbinal.indb i 111/21/20071/21/2007 111:41:061:41:06 AAMM GALACTIC THE OHIO STATE Columbus YYaszekaszek ffinal.indbinal.indb iiii 111/21/20071/21/2007 111:41:171:41:17 AAMM SUBURBIA RRECOVERINGE CO V E R I N G WWOMEN’SO M E N ’ S SSCIENCECI E N C E FICTIONF I CT I O N LISA YASZEK UNIVERSITY PRESS YYaszekaszek ffinal.indbinal.indb iiiiii 111/21/20071/21/2007 111:41:171:41:17 AAMM Copyright © 2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yaszek, Lisa, 1969– Galactic suburbia : recovering women’s science fi ction / Lisa Yaszek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978–0–8142–1075–8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978–0–8142–5164–5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Science fi ction, American—History and criticism. 2. American fi ction—Women authors—History and criticism. 3. American fi ction—20th century—History and criti- cism. 4. Feminism and literature—United States—History—20th century. 5. Women and literature—United States—History—20th century. 6. Feminist fi ction, American— History and criticism. 7. Sex role in literature. I. Title. PS374.S35Y36 2008 813.’08762099287—dc22 2007032288 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978–0–8142–1075–8) Paper (ISBN 978–0–8142–5164–5) CD ROM (ISBN 978–0–8142–9153–5) Cover design by Dan O’Dair. Text design by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe. Type set in ITC Veljovic. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc.