New Directions in Contemporary Music Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Conception, Para-Musical Events and Stage Performance in Jani Christou’S Strychnine Lady (1967)

Musical conception, para-musical events and stage performance in Jani Christou’s Strychnine Lady (1967) Giorgos Sakallieros Department of Music Studies, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] Konstantinos Kyriakos Department of Theatre Studies, University of Patras, Greece [email protected] Proceedings of the fourth Conference on Interdisciplinary Musicology (CIM08) Thessaloniki, Greece, 3-6 July 2008, http://web.auth.gr/cim08/ Background in music analysis. Jani Christou (1926-1970) was a eminent Greek avant-garde composer who expanded the traditional aesthetics of musical conception, as well as of concert and stage performance, to a whole new art-form that involved music, philosophy, psychology, mythical archetypes, and dramatic setting. His ideals and envisagements, constantly evolving from the late 1950s, are profoundly denoted in his late works, created between 1965-1968 (Mysterion, Anaparastasis I – III, Epicycle, Strychnine Lady). These works, originally conceived as ‘stage rituals’, include instrumental performance, singing, acting, dance, tape and visual effects, and thus combine musical and para-musical events and gestures. Background in theatre studies. From the early 1960s music theatre comprised a major field of avant-garde composition in which spectacle and dramatic impact were emphasized over purely musical factors. Avant-garde performance trends and media, such as Fluxus or happenings, had a significant impact on several post-war composers both in Europe and North America (i.e. Cage, Ligeti, Berio, Nono, Kagel, Henze, Stockhausen, Birtwistle and Maxwell Davies), which led to the establishment and flourish of the experimental music theatre during the 1960s and 1970s. The use of new dramatic and musical means combined elements of song, dance, mimic, acting, tape, video and visual effects which could be tailored to a wide range of performing spaces. -

New Directions: Olivier, Branagh, and Shakespeare's "Henry V"

New Directions: Olivier, Branagh, and Shakespeare’s Henry V A Senior Honors Thesis By Michael Descy Under the Guidance of Professor William Flesch For The Department of English Brandeis University Spring 2000 -1- Shakespeare Versus Film Shakespeare’s ongoing popularity, durability, and quality make his plays popular source material for movies. Countless films, from Kurosawa’s Ran to the recent teen comedy 10 Things I Hate About You, are adaptations of Shakespeare plays. For the most part, though, these films tend to be as far away from Shakespeare as Shakespeare was from his source material—they are not Shakespeare films as academics define them. True Shakespeare films are adaptations that strive to retain as much of the language and carry the same intent of the original plays. Inevitably, they must also carry the vision of their directors, and the source material must be altered, sometimes drastically, to suit the screen. Putting Shakespeare on film is not easy. As adaptations go, they face a unique set of problems that are compounded by both the audience’s familiarity with the plays, which raises expectations for the movie, and with the audience’s unfamiliarity with Shakespeare’s Elizabethan language in film settings. The plays themselves also run far longer than the traditional movie length of two hours, which puts added strain on a typical movie audience. The language is far more dense, voluminous, and descriptive than normal movie dialogue, which makes the words seem redundant and the movie overly “talky.” Finally, the texts themselves are so entrenched in our culture that they approach sacred works, which renders the necessary cutting and continuity editing sacrilege. -

Download Download

Teresa de Lauretis Futurism: A Postmodern View* The importance of Modernism and of the artistic movements of the first twenty or so years of this century need not be stressed. It is now widely acknowledged that the "historical avant-garde" was the crucible for most of the art forms and theories of art that made up the contemporary esthetic climate. This is evidenced, more than by the recently coined academic terms "neoavanguardia" and "postmodernism," 1 by objective trends in the culture of the last two decades: the demand for closer ties between artistic perfor- mance and real-life interaction, which presupposes a view of art as social communicative behavior; the antitraditionalist thrust toward interdisciplinary or even non-disciplinary academic curri- cula; the experimental character of all artistic production; the increased awareness of the material qualities of art and its depen- dence on physical and technological possibilities, on the one hand; on the other, its dependence on social conventions or semiotic codes that can be exposed, broken, rearranged, transformed. I think we can agree that the multi-directional thrust of the arts and their expansion to the social and the pragmatic domain, the attempts to break down distinctions between highbrow and popular art, the widening of the esthetic sphere to encompass an unprecedented range of phenomena, the sense of fast, continual movement in the culture, of rapid obsolescence and a potential transformability of forms are issues characteristic of our time. Many were already implicit, often explicit, in the project of the historical avant-garde. But whereas this connection has been established and pursued for Surrealism and Dada, for example, Italian Futurism has remained rather peripheral in the current reassessment; indeed one could say that it has been marginalized and effectively ignored. -

Monash's Public Sector Management Institute Gets A$1.5M Boost

• Monash's Public Sector ~~ Management Institute gets a$1.5m boost ~ The Federal Government has granted the university 51.S million over the next two and a half years towards expanding tbe recently-eslablished Public. AMAGAZINE FORTHE UNIVERSITY Sector Management Institute witbin tbe Graduate School of Management. Registered by Australia Post - publication No. VBG0435 The grant, announced by the Minister the Minister for Transport and Com NUMBER 4-88 JUNE 8, 1988 for Employment, Education and Train munications. Senator Gareth Evans. ing, Mr John Dawkins, represents the Professor Chris Selby·Smith will be lion's share of $1.8 million set aside in responsible for health policy and the last budget as the National Public management, and the chairman of the Sector Management Study Fund. Economics department, Professor John Gun lobby's aim: "To According to its director, Professor Head, for tax and expenditure Allan Fels, the primary thrust of the new administration. He will co-operate in the institute will be research, but it wiD also area of tax. law with Professor Yuri involve itself in teaching non-degree Grbich. a former Monash academic, intimidate government courses, providing in-service training for now at the University of New South public sector managers and carrying out Wales Law School. contract research for Australian and The position of Professor of Public foreign governments and private sector Sector Management, concerned with in the frontier society" organisations. effectiveness and efficiency in the public In addition to the successful tender to service, has been advertised. It is ex Australian sbooten are travelling down a well"trodden American road, says noted the Commonwealth, the institute has pected that an appointment will be made lua coatrol lobbyist, Joba Crook, la b1s Master of Arts tbesls. -

New Directions in the Humanities Nuevas Tendencias En Humanidades

XVII Congreso Internacional sobre Seventeenth International Conference on Nuevas Tendencias New Directions in en Humanidades the Humanities El Mundo 4.0: Convergencias de The World 4.0: Convergences of máquinas y conocimientos Knowledges and Machines 3–5 de julio de 2019 3–5 July 2019 Universidad de Granada University of Granada Granada, España Granada, Spain Las-Humanidades.com TheHumanities.com facebook.com/NuevasTendenciasEnHumanidades facebook.com/NewDirectionsintheHumanities twitter.com/OnTheHumanities | #ICNDH19 twitter.com/OnTheHumanities | #ICNDH19 Seventeenth International Conference on New Directions in the Humanities “The World 4.0: Convergences of Knowledges and Machines” 3–5 July 2019 | University of Granada | Granada, Spain www.TheHumanities.com www.facebook.com/NewDirectionsintheHumanities @onthehumanities | #ICNDH19 XVII Congreso Internacional sobre Nuevas Tendencias en Humanidades “El Mundo 4.0: Convergencias de máquinas y conocimientoss” 3–5 de julio de 2019 | Universidad de Granada | Granada, España www.las-humanidades.com www.facebook.com/NuevasTendenciasEnHumanidades/ @onthehumanities | #ICNDH19 Seventeenth International Conference on New Directions in the Humanities www.thehumanities.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). Common Ground Research Networks may at times take pictures of plenary sessions, presentation rooms, and conference activities which may be used on Common Ground’s various social media sites or websites. -

Michael Pelzel Gravity’S Rainbow 2

Michael Pelzel Gravity’s Rainbow 2 Michael Pelzel 3 Michael Pelzel: Gravity’s Rainbow 4 1. Mysterious Anjuna Bell (2016) 18:47 für Ensemble und Kammerorchester Ensemble ascolta und Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, Peter Rundel (Leitung) 2. Carnaticaphobia (2017) 16:18 für Perkussion, Klavier und Violoncello ensemble recherche 3. Gravity’s Rainbow (2016) 21:00 für CLEX (Kontrabassklarinette extended) und Orchester Ernesto Molinari (CLEX), Basel Sinfonietta, Peter Rundel (Leitung) 4. „Alf“-Sonata (2014) 08:25 5 für Violine und Horn Jetpack Bellerive: Noëlle-Anne Darbellay (Violine) und Samuel Stoll (Horn) Danse diabolique (2016) für Bläser, Harfe, Orgel, Klavier und Schlagzeug WDR Sinfonieorchester, Bas Wiegers (Leitung) 5. I. Introduction 03:28 6. II. Danse diabolique 08:25 Gesamtspieldauer 76:26 Im Sog des Klangstroms 6 Ein Klang, so überwältigend reich und vielfältig, dass er das Ensemble, das ihn hervorbringt, geradezu transzendiert. Eine Fülle an Farben, die ans Maß- lose grenzt. Ein Gewimmel von Gestalten, das die Ohren überfordert. Ein Ganzes, das weit mehr ist als seine Teile, doch ohne diese zu verschlucken. Solcherart mögen die ersten Eindrücke sein, die man von der Musik Michael Pelzels empfängt. Viel (und vieles zugleich) geschieht in ihr, und wer sie unbefangen hört, wird sich von ihr geradezu aufgesogen fühlen, hinein- gestoßen ins Klanggeschehen und zunächst einmal aller refl exiven Distanz beraubt. Tatsächlich hat diese Musik in der Üppigkeit ihrer Mittel etwas Dionysisches, Anarchisch-Ungebundenes – was freilich keineswegs einen Verzicht auf planvolle Strukturierung und kompositorisches Kalkül bedeutet. Ganz im Gegenteil: Die erste Lektion allen Kunstmachens, dass der ästhe- tische Schein von Freiheit gerade nicht aus einer völligen Freiheit des Ge- staltens resultiert, ist selbstverständlich auch Michael Pelzel geläufi g. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a Study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and His Effect on the Trumpet

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet Michael Joseph Berthelot Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berthelot, Michael Joseph, "A Symphonic Poem on Dante's Inferno and a study on Karlheinz Stockhausen and his effect on the trumpet" (2008). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SYMPHONIC POEM ON DANTE’S INFERNO AND A STUDY ON KARLHEINZ STOCKHAUSEN AND HIS EFFECT ON THE TRUMPET A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by Michael J Berthelot B.M., Louisiana State University, 2000 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2006 December 2008 Jackie ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dinos Constantinides most of all, because it was his constant support that made this dissertation possible. His patience in guiding me through this entire process was remarkable. It was Dr. Constantinides that taught great things to me about composition, music, and life. -

Volume L, No 3, July-September 2012

Cyprus TODAY Volume L, No 3, July-September 2012 Contents EDITORIAL ....................................................................4 Kypria International Festival 2012 ...................................6 Mapping Cyprus: Crusaders, Traders and Explorers ......14 Maniera Cypria ...............................................................19 4th Cypriot Film Directors Festival .................................22 4th International Pharos Contemporary Music Festival ..28 16th International Festival of Ancient Greek Drama .......36 Cyprus Medical Museum ...............................................41 Pafos Aphrodite Festival 2012 ........................................44 Terra Mediterranea-In Crisis ...........................................48 Cypriot Armenian Artists Exhibition .............................52 United States of Europe .................................................56 Bokoros “Odos Eleftherias” ............................................63 The World Youth Choir in Cyprus ..................................65 Volume L, No 3, July-September 2012 A quarterly cultural review of the Ministry of Education and Editorial Supervision: Culture published and distributed by the Press and Information Miltos Miltiadou (PΙΟ) Offi ce (PIO), Ministry of Interior, Nicosia, Cyprus. E-mail: [email protected] Address: Editorial Assistance: Ministry of Education and Culture Maria Georgiou (PΙΟ) Kimonos & Thoukydides Corner, 1434 Nicosia, Cyprus E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.moec.gov.cy David A. Porter E-mail: -

An Introductory Survey on the Development of Australian Art Song with a Catalog and Bibliography of Selected Works from the 19Th Through 21St Centuries

AN INTRODUCTORY SURVEY ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUSTRALIAN ART SONG WITH A CATALOG AND BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SELECTED WORKS FROM THE 19TH THROUGH 21ST CENTURIES BY JOHN C. HOWELL Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. __________________________________________ Mary Ann Hart, Research Director and Chairperson ________________________________________ Gary Arvin ________________________________________ Costanza Cuccaro ________________________________________ Brent Gault ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to so many wonderful individuals for their encouragement and direction throughout the course of this project. The support and generosity I have received along the way is truly overwhelming. It is with my sincerest gratitude that I extend my thanks to my friends and colleagues in Australia and America. The Australian-American Fulbright Commission in Canberra, ACT, Australia, gave me the means for which I could undertake research, and my appreciation goes to the staff, specifically Lyndell Wilson, Program Manager 2005-2013, and Mark Darby, Executive Director 2000-2009. The staff at the Sydney Conservatorium, University of Sydney, welcomed me enthusiastically, and I am extremely grateful to Neil McEwan, Director of Choral Ensembles, and David Miller, Senior Lecturer and Chair of Piano Accompaniment Unit, for your selfless time, valuable insight, and encouragement. It was a privilege to make music together, and you showed me how to be a true Aussie. The staff at the Australian Music Centre, specifically Judith Foster and John Davis, graciously let me set up camp in their library, and I am extremely thankful for their kindness and assistance throughout the years. -

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

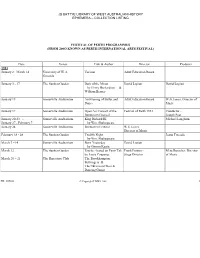

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

Contem Porary M Usic

fe stival of contempo rary mu sic MUSIC CENTER AUGUST 9 –13 • 2 012 TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER an activity of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Mark Volpe, Eunice and Julian Cohen Managing Director, endowed in perpetuity Ellen Highstein, Edward H. Linde Tanglewood Music Center Director, endowed by Alan S. Bressler and Edward I. Rudman Tanglewood Music Center Staff Library Audio Department John Perkel Timothy Martyn Andrew Leeson Melissa Steinberg Technical Director/Chief Budget and Office Manager Orchestra Librarians Engineer Karen Leopardi Stephen Jean Douglas McKinnie Associate Director for Faculty and Head Librarian, Copland Library Audio Engineer, Head of Live Guest Artists Sound Emily Sapa Michael Nock Assistant Librarian, Copland Library Charlie Post Associate Director for Student Affairs Senior Audio Engineer Gary Wallen Production Nicholas Squire Associate Director for Scheduling John Morin Audio Engineer and assistant and Production Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Hall Radio Engineer Ryland Bennett Matthew Baltrucki Associate Audio Engineer 2012 SUMMER STAFF Assistant Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Hall Piano Administrative Ryan P. Collins Steve Carver Catelyn Cohen Michael Hawes Chief Piano Technician Personnel Manager Peter Lillpopp Barbara Renner Eric Dluzniewski Leonardo Perez Chief Piano Technician Scheduling Assistant Adam Wing Erik Diehl Alisa Forman Stage Assistants, Seiji Ozawa Hall Assistant Piano Technician Front Desk Assistant Katherine Ludington Dormitory Artist Assistant/Driver Michelle Keem Dormitory Supervisor Erin Svoboda Assistant