Contem Porary M Usic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

British and Commonwealth Concertos from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers I-P JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) Born in Bowdon, Cheshire. He studied at the Royal College of Music with Stanford and simultaneously worked as a professional organist. He continued his career as an organist after graduation and also held a teaching position at the Royal College. Being also an excellent pianist he composed a lot of solo works for this instrument but in addition to the Piano Concerto he is best known for his for his orchestral pieces, especially the London Overture, and several choral works. Piano Concerto in E flat major (1930) Mark Bebbington (piano)/David Curti/Orchestra of the Swan ( + Bax: Piano Concertino) SOMM 093 (2009) Colin Horsley (piano)/Basil Cameron/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra EMI BRITISH COMPOSERS 352279-2 (2 CDs) (2006) (original LP release: HMV CLP1182) (1958) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra (rec. 1949) ( + The Forgotten Rite and These Things Shall Be) LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO 0041 (2009) Eileen Joyce (piano)/Leslie Heward/Hallé Orchestra (rec. 1942) ( + Moeran: Symphony in G minor) DUTTON LABORATORIES CDBP 9807 (2011) (original LP release: HMV TREASURY EM290462-3 {2 LPs}) (1985) Piers Lane (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/Ulster Orchestra ( + Legend and Delius: Piano Concerto) HYPERION CDA67296 (2006) John Lenehan (piano)/John Wilson/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend, First Rhapsody, Pastoral, Indian Summer, A Sea Idyll and Three Dances) NAXOS 8572598 (2011) MusicWeb International Updated: August 2020 British & Commonwealth Concertos I-P Eric Parkin (piano)/Sir Adrian Boult/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + These Things Shall Be, Legend, Satyricon Overture and 2 Symphonic Studies) LYRITA SRCD.241 (2007) (original LP release: LYRITA SRCS.36 (1968) Eric Parkin (piano)/Bryden Thomson/London Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Legend and Mai-Dun) CHANDOS CHAN 8461 (1986) Kathryn Stott (piano)/Sir Andrew Davis/BBC Symphony Orchestra (rec. -

Getting There2 W CM Obit.Indd

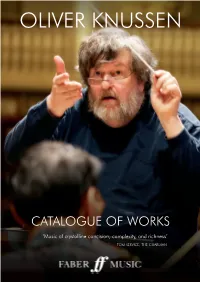

OLIVER KNUSSEN CATALOGUE OF WORKS ‘Music of crystalline concision, complexity, and richness’ TOM SERVICE, THE GUARDIAN OLIVER KNUSSEN 1952–2018 Abbreviations WOODWIND picc piccolo fl flute Oliver Knussen was a towering figure in contemporary music, as composer and conductor, afl alto flute teacher and artistic director. The relatively small size of his compositional output conceals bfl bass flute ob oboe music of exceptional refinement and subtlety – few bars of Knussen may have more impact bob bass oboe than whole movements by lesser composers. Besides definitive interpretations of his own ca cor anglais music he must surely have given more first performances than any other conductor, alongside acl alto clarinet E¨cl clarinet (E¨) an outstanding body of recordings. He was the central focus of so many activities, and an cl clarinet irreplaceable mentor to his fellow composers, who constantly sought and relied on his advice bcl bass clarinet and encouragement. cbcl contra bass clarinet bsn bassoon cbsn contra bassoon He was born in Glasgow; his father Stuart Knussen was principal double bass of the London ssax soprano saxophone Symphony Orchestra for nearly 20 years. Although he would have laughed at any idea of his asax alto saxophone tsax tenor saxophone being a child prodigy this gave him an unrivalled insight into the workings of the orchestra bsax baritone saxophone from an early age. It culminated in his conducting his First Symphony with the LSO at the BRASS age of 15, when their principal conductor István Kertész fell ill. His father played in the first hn horn performance of Benjamin Britten’s church parable Curlew River in 1964. -

The Fires of London

The Fires of London THE FIRES OF LONDON (FORMERLY THE PIERROT PLAYERS) 1967 – 1987 1. The Pierrot Players and The Fires of London – a history 1967-75 2. Eight songs for a Mad King - 1969 3. Vesalii Icones - 1969 4. Miss Donnithorne’s Maggot - 1974 5. Ave Maris Stella - 1975 6. Arts Council Contemporary Music Network Tour - 1975 7. Charity Commission 1975-76 8. Peter Maxwell Davies’ Disappearance/First visit to Orkney – January 1976 9. Television relay of Eight Songs for a Mad King 10. North American Tour – October-November 1976 11. Latin American Tour – March- April 1977 12. First St. Magnus Festival/ The Martyrdom of St. Magnus June 1977 13. Tour of Hungary – October 1977 14. Residency at Bayerische Staatsoper, Munich – April 1978 15. Le Jongleur de Notre Dame 1978 16. Touring The Martyrdom of St. Magnus 1978-79 17. Tour of Australia and New Zealand March 1980 18. Musicians Union Strike Prom July August 1980 19. The Lighthouse – 1980 20. Touring The Lighthouse – Summer 1981 21. Arts Council Contemporary Network Tour – 1982 22. Image Reflection shadow - 1982 23. Sacra Umbra Festival - Sept 1982 24. Birthday Music for John 25 - Jan 1983 25. Britain Salutes New York Festival – April 1983 26. The No. 11 Bus –March 19844 27. Tour of North America - November 1985 28. Other Composers 29. Elliott Carter/Hans Werner Henze 30. Fires Farewell – January 1987 31. Composers performed by The Fires of London 32. Principal Players and Associates of The Fires of London Note In my memories of The Fires of London, hereinafter referred to as The Fires, I will attempt to give the main outline of the history and chief events during my period as Manager from October 1975 until January 1987. -

Mark-Anthony Turnage

with Twisted Ballad, which includes two treatments of Led Zeppelin numbers. Mark-Anthony Turnage More predictably, perhaps, his love of different popular genres shines through his opera Anna Nicole, investing its tragicomic story with American local colouring and a "feel-good factor" which is typically ironic. But it is characteristic of Turnage that in the wake of Anna Nicole he composed two major works exploring entirely different areas of musical expression: the Cello Concerto harking back to English tradition, with allusions to Elgar; the ambitious Speranza full of melodies inspired by various folk traditions. These new departures reflect the questioning, pluralist outlook which has led Turnage to say in an interview: "I don’t want to write the same Mark-Anthony Turnage photo © Philip Gatward type of music. I want to push myself." And wherever his future explorations may take him, the results will surely continue to attract, intrigue and entertain __An introduction to the music of Mark-Anthony Turnage__ _by Anthony audiences. Burton_ In his fifties, Mark-Anthony Turnage is one of the best known British composers of his generation, widely admired for his highly personal mixture of Anthony Burton, 2013 energy and elegy, tough and tender. His productivity is impressive, the result (Anthony Burton is a former BBC Radio 3 producer and presenter, now a of single-minded concentration on the job in hand. But his solitary hours at his freelance writer on music.) desk are broken up by fruitful interaction with the musicians who are to interpret his works. The methods he has established over the years depend heavily on co-operation: collaborations with soloists in the creation of new works which are both showcases and challenges; creative partnerships with improvising jazz performers; residencies and close associations with orchestras and opera companies which allow him to try out his scores under workshop conditions before he brings them – often with radical changes – to their final form. -

A Snapshot of the Pierrot Ensemble Today

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Dromey, Christopher ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3275-4777 (2013) A Snapshot of the Pierrot Ensemble Today. Proceedings of the Third International Meeting for Chamber Music . [Article] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/9885/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

'Resonance and Distance': Simon Bainbridge in Conversation

Tempo 67 (265) 37–49 © 2013 Cambridge University Press 37 doi:10.1017/S0040298213000454 ‘resonance and distance’: simon bainbridge in conversation Malcolm Miller Abstract: This interview, based on a conversation with Simon Bainbridge at London’s City Literary Institute in June 2011, presents something of a rounded portrait of the composer while covering a good deal of ground. We began our conversation with a discussion of a recent work for orchestra, Concerti Grossi, going into some detail in matters of scoring and structure. The discussion then broadened to cover such topics as the creative process, formative influences (for example, his parents’ activity in the visual arts, Debussy’s Jeux, John Lambert and Gunther Schuller), instrumentation and the relationship of music and text. This led on specifically to Bainbridge’s settings of Primo Levi, in for example the cycle Ad Ora Incerta, and to a consider- ation of the composer’s relationship with the audience. The British composer Simon Bainbridge marked his 60th birthday with the world première of his Garden of Earthly Delights, given at the BBC Proms on 18 August 2012. Whilst in the early stages of work on that piece Bainbridge generously agreed to an interview and a discussion on 24 June 2011, in a class as part of my course ‘New Music: Where is the Avant-Garde Today?’ at the City Literary Institute (Holborn, London). I am grateful to all students for their stimulus and enthusiasm in our discovery of Simon Bainbridge’s oeuvre. Since the interview took place, Bainbridge has composed several chamber works and is currently involved in a projected col- laboration writing a concertante work for the legendary American-Puerto Rican jazz bassist Eddie Gomez. -

Introduction

Introduction This DMus submission, entitled Translating Twenty-First-Century Orchestral Scores for the Piano: Transcription, Reduction and Performability, sets out to explore the field of practical piano reductions of contemporary orchestral scores, with piano concertos at the centre of attention. The research is focussed around two case studies, and this part of the submission consists of complete reductions of the orchestral parts of works for piano and orchestra by the living British composers Mark-Anthony Turnage and James Dillon. Both reductions have been created by the researcher; and are intended to be viable for use in professional situations; both have received the full endorsement of their respective composers. Because there so far exist very few published piano reductions of twenty-first-century orchestral scores, what professional piano accompaniment practice there is in this field tends to rely on score-reading techniques to produce an adequate representation of acoustic impressions of the orchestral material, whose soundscape often includes elements that transcend traditional pitch-based sound production. As a result, solutions are highly subjective, typically made spontaneously, and as often as not, ultimately fail to provide adequate support for the soloist in either rehearsal or performance. My research over the past six years has been an iterative process, consistently based on my own practice as a professional collaborative pianist, coupled with deeper analysis of the original orchestral materials than is normally possible in the little time available in the professional working environment. A further aim has been to come as close as possible to producing publishable – and therefore reproducible – piano reductions of the orchestral parts for the two works investigated in the case studies. -

New Directions in Contemporary Music Theatre

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1986 New directions in contemporary music theatre Lynette Frances Williams University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Williams, Lynette Frances, New directions in contemporary music theatre, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, School of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1986. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2260 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

Peter Maxwell Davies ST. THOMAS WAKE Foxtrot for Orchestra Richard

Side 1 (2Q57) beloved of the English virginalists and the in a distinct style. Over the last of these dances, the lovelorn, and must surely be the only com- Peter Maxwell Davies modem American ballroom step is curiously the orchestra starts a slow, declamatory rework- poser to have been made an honom ry member ST. THOMAS WAKE convincing, and the work earned this accolade ing of its material, leading to a further fast of the Paris police force for his study of glan- Foxtrot for Orchestra from The Daily Telegraph: "The skill and the "commentary" upon all five foxtrots. A final dular disturbances in criminals! Richard Duffallo, conductor imagination shown in this montage of two pasts, foxtrot from the band cuts across this, having Hollywood offered Antheil the security to one present and an ugly implied future rivals the exact harmonic skeleton of the John Bull continue serious composition, and his music Side 2 (2200) Stravinsky in his experiments with musical Pavan, which is now heard simultaneously from after his move there in 1936 seems to blend his George Antheil time." the harp in the orchestm in its original form. personal modernism with a more moderate ac- SYMPHONY NO. S There is no attempt to integrate the styles of cessible style. The Fifth Symphony, subtitled (1)829 the band and the symphony orchestra - each "Joyous," represents in addition a marked de- . (2) 654 Raised in Manchester and educated at the goes its own way on its own terms. The use of parture from the pessimism and pathos of the (3)630 Royal Manchester College of Music and Man- the separate band is not meant to imply in any Third (1942) and Fourth (1944), written in the chester University, Peter Maxwell Davies is at sense a kind of sinfonia concertante nor even a midst of World War 11. -

Thesis Final Submission

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ ‘Max-imising’ madness in music the gift of madness in the music of Peter Maxwell Davies Mesbahian, Fetemeh Upa Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 ‘Max-imising’ Madness in Music: The Gift of Madness in the Music of Peter Maxwell Davies Upa Mesbahian King’s College London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music March 2019 !1 Abstract Perhaps no composer of the twentieth century has shown as much fascination with the topic of madness as British composer Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016). -

© Copyright 2015 Hyunju Juno Lee

© Copyright 2015 Hyunju Juno Lee Behind the Masks Performance DVD and Thesis Of Masks, Op. 3 (1969) for solo flute and glass chimes ‘ad lib.’ by Oliver Knussen Hyunju Juno Lee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Donna Shin, Chair Timothy Salzman Christina Sunardi Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music University of Washington Abstract Behind the Masks Hyunju Juno Lee Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Donna Shin School of Music Masks, Op. 3 for solo flute and glass chimes 'ad lib.' was written by British composer Oliver Knussen in 1969. Masks confirms itself as the highest art form for the solo flute. Masks is a story about an individual going through different stages of emotions, and it describes each state of mind by layering innovative performance techniques such as grimaces and head jerks. The ideas about stage usage, physical gestures, and compositional settings merge delicately yet persuasively into this ten-minute monodrama. A discussion of Oliver Knussen’s biography, a thorough study of Masks’ manuscript, and analysis of the gestural structure and the compositional organization of the work examines the importance of Masks as a pivotal work for the development of flute literature. The author’s performance project, Chronicle I. Mask features Masks, Op. 3 as a center piece to celebrate its significance and share a compelling experience with the audience. Performance guidance addresses the practical considerations to achieve an ideal performance for Masks in five following aspects: stage preparation, sound, tempo, motions, and memorization.