A Snapshot of the Pierrot Ensemble Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Susanna Hancock Music

Susanna Hancock Curriculum Vitae 11 Maysville Ave. susannahancockmusic.com Mt. Sterling, KY 40353 [email protected] (321) 759-2594 [email protected] B I O G R A P H I C A L O V E R V I E W Susanna Hancock is an Asian-American composer whose works explore color, process, and acoustic phenomena. Her music draws from a wide array of influences including minimalism, spectralism, folk, and electronic mediums. Susanna’s music has been played by the JACK Quartet, ZAFA Collective, and Metropolis Ensemble, and members of the St. Louis Symphony. Her compositions have been featured in concerts and festivals throughout the world including the Bang on a Can Summer Music Festival and Dimitria Festival in Thessaloniki, Greece. Susanna is currently an Artist in Residence at National Sawdust with Kinds of Kings, a composer collective dedicated to making the music community a more equitable and inclusive space. She is also Co-Founder and Co-Artistic Director of Terroir New Music, a concert/event series that pairs the music of living composers with craft food and drink. E D U C A T I O N 2016 Master of Music Music Theory & Composition New York University | Steinhardt GPA: 4.0, Summa Cum Laude 2014 Bachelor of Music Acoustic/Electronic Composition, Bassoon Performance University of South Florida GPA: 3.97, Summa Cum Laude, With Honors 2010 Associate of Arts Eastern Florida State College (Formerly Brevard Community College) GPA: 4.0, Summa Cum Laude, With Honors *Conferred upon high school graduation P R I V A T E I N S T R U C T I O -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

Academic Career Selected Awards and Commissions

CURRICULUM VITAE JUDITH SHATIN 1938 Lewis Mountain Rd. Charlottesville, VA 22903 [email protected] Education 1979 Princeton Ph.D. University 1976 MFA 1974 The Juilliard MM (Abraham Ellstein Award) School 1971 Douglass College AB (Phi Beta Kappa, Graduation with Honors) Academic Career 2018- University of Virginia William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor Emerita 1999- 2018 University of Virginia William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor 1995-2002 University of Virginia Chair, McIntire Department of Music 1990-1999 University of Virginia Professor 1987- Virginia Center for Founder Computer Music 1985-1989 University of Virginia Associate Professor 1979-1984 University of Virginia Assistant Professor Selected Awards and Commissions Date Source Type Work 2020 Kassia Ensemble Commission Kassia’s Song 2020 YIVO Commission unter soreles vigele 2019 Bennington Chamber Commission Cinqchronie Music Festival 2019 Fintan Farrelly Commission In a Flash 2019 San Jose Chamber Commission Respecting the First Orchestra (Amendment) 2018 Illinois Wesleyan Commission I Love University 2018 Amy Johnson Commission Patterns 2017 San Jose Chamber Commission Ice Becomes Water Orchestra 2017 Gail Archer Commission Dust & Shadow 2016 Carnegie Hall and the Commission Black Moon Judith Shatin American Composers Orchestra 2016 Ensemble of These Times Commission A Line-Storm Song & the LA Jewish Music Commission 2015 Clay Endowment Fellowship Trace Elements Project 2015 Atar Trio Commission Gregor’s Dream 2015 Ensemble Musica Nova – Commission Storm Tel Aviv 2014-15 UVA Percussion -

Contem Porary M Usic

fe stival of contempo rary mu sic MUSIC CENTER AUGUST 9 –13 • 2 012 TANGLEWOOD MUSIC CENTER an activity of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Mark Volpe, Eunice and Julian Cohen Managing Director, endowed in perpetuity Ellen Highstein, Edward H. Linde Tanglewood Music Center Director, endowed by Alan S. Bressler and Edward I. Rudman Tanglewood Music Center Staff Library Audio Department John Perkel Timothy Martyn Andrew Leeson Melissa Steinberg Technical Director/Chief Budget and Office Manager Orchestra Librarians Engineer Karen Leopardi Stephen Jean Douglas McKinnie Associate Director for Faculty and Head Librarian, Copland Library Audio Engineer, Head of Live Guest Artists Sound Emily Sapa Michael Nock Assistant Librarian, Copland Library Charlie Post Associate Director for Student Affairs Senior Audio Engineer Gary Wallen Production Nicholas Squire Associate Director for Scheduling John Morin Audio Engineer and assistant and Production Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Hall Radio Engineer Ryland Bennett Matthew Baltrucki Associate Audio Engineer 2012 SUMMER STAFF Assistant Stage Manager, Seiji Ozawa Hall Piano Administrative Ryan P. Collins Steve Carver Catelyn Cohen Michael Hawes Chief Piano Technician Personnel Manager Peter Lillpopp Barbara Renner Eric Dluzniewski Leonardo Perez Chief Piano Technician Scheduling Assistant Adam Wing Erik Diehl Alisa Forman Stage Assistants, Seiji Ozawa Hall Assistant Piano Technician Front Desk Assistant Katherine Ludington Dormitory Artist Assistant/Driver Michelle Keem Dormitory Supervisor Erin Svoboda Assistant -

Katherine Balch Composition List

KATHERINE BALCH, composer LIST OF COMPOSITIONS Instrumental - Large Ensemble Illuminate for 2 sopranos, mezzo-soprano, and orchestra (35 minutes) (2020) (2/2/2/2/2/2/ten. tbn/ bs. tbn./timp+2 perc/harp/solo soprano/solo soprano/solo mezzo- soprano/strings) Commissioned by the California Symphony Premiere by the California Symphony conducted by Donato Cabrera on March 14, 2020 canceled due to COVID-19 impromptu for orchestra (5 minutes) (2019) (3/3/3/3/4/3/2/1/timp+2 perc/harp/strings) Commissioned by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Premiered by the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Krzysztof Urbanski on the Lily Classical Series, January 24, 2020 at Hilbert Circle Theater (Indianapolis, IN) Artifacts for violin and orchestra (25 minutes) (2019) (2/2/2/2/4/2/2/1/timp+2 perc/solo violin/strings) Commissioned by the California Symphony Premiered by violinist Robyn Bollinger and the California Symphony conducted by Donato Cabrera on May 5, 2019 at Lesher Center for the Arts (Walnut Creek, CA) Chamber Music for orchestra (11 minutes) (2018) (3/2+eng. horn/2+ bs. cl./2/4/2/2/1/timp + 3 perc/pno/harp/strings) Commissioned by the Oregon Symphony Orchestra Premiered by the Oregon Symphony Orchestra conducted by Jun Märkl on September 29, 2018 at Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall (Portland, OR) like a broken clock for orchestra (10 minutes) (2018) (2/2/2/2/4/2/2/1/timp/strings) Commissioned by the California Symphony Premiered by the California Symphony conducted by Donato Cabrera on May 3, 2018 at Lesher Center for the Arts (Walnut Creek, -

Pierrot Ensemble

UCLA Contemporary Music Score Collection Title Three Precocious Children's Poems Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9zm4f5f3 Author Van Tassel, Charles Publication Date 2020 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Three Precocious Children’s Poems By Charles M. Van Tassel Three Precocious Children’s Poems By Charles M. Van Tassel Text by Blair Dishon (5:00’) Instrumentation: Flute Clarinet in Bb/Bass Clarinet Marimba Piano Soprano Voice Violin Cello I. Hairflowers Charles M. Van Tassel q = 152 Text by Blair Dishon Flute ° U U U &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 Ó Œ œ ppp U U U Clarinet in Bb &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 Ó ˙ ¢ ppp U U U &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ Marimba U U U ? 4 ∑ 1 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 1 ∑ 4 ∑ { 4 4 4 4 4 U U U &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ Piano U U U ? 4 ∑ 1 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 1 ∑ 4 ∑ { 4 4 4 4 4 U U U Soprano &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ q = 152 Violin ° U U U &4 ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ ∑ 41 ∑ 4 ∑ normale U U : % ; sul pont. : % ; sul pont. U Violoncello ? 4 1 ∑ 4 w~ 1 ∑ 4 4ww~ 4 4 w 4 4 ¢ pp w mf pp w mf Copyright © 2017 2 7 accel. rit. accel. rit. Fl. ° œ œ œ œ œ™ œ & w œ Œ Ó Ó Œ œ w œ Œ Ó ∑ ‰™ mf ppp ppp mf ppp mp p . Cl. #œ™ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ & w ˙ Ó Ó ˙ w ˙ Ó ∑ ¢ mf ppp ppp mf ppp mp f mp 3 3 3 3 ∑ ∑ Ó ∑ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ∑ Ó & œ œ œ œ œ œ æ æ p. -

Louis Fleury and the Early Life of Pierrot Lunaire

VOLUME 3 9 , NO . 1 F ALL 2 0 1 3 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Louis Fleury and the Early Life of Pierrot lunaire The Center of Gravity in Flute Pedagogy and Performance The Inner Flute: A Transcript of Music and Words THEOFFICIALMAGAZINEOFTHENATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATION, INC 695RB-CODA Split E THE ONLY SERIES WHERE CUSTOM Sterling Silver Lip Plate IS COMPLETELY STANDARD 1ok Gold Lip Plate Dolce and Elegante Series instruments from Pearl offer custom performance options to the aspiring C# TrillC# Key student and a level of artisan craftsmanship as found on no other instrument in this price range. Choose B Footjoint from a variety of personalized options that make this flute perform like it was hand made just for you. Dolce and Elegante Series instruments are available in 12 unique models starting at just $1600, and like all Pearl flutes, they feature our advanced pinless mechanism for fast, fluid action and years of reliable service. Dolce and Elegante. When you compare them to other flutes in this price range, you’ll find there is no comparison. pearlflutes.com Table of CONTENTSTHE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME 39, NO. 1 FALL 2013 DEPARTMENTS 11 From the Chair 47 Passing Tones 13 From the Executive Director 52 Honor Roll of Donors to the NFA 16 High Notes 54 New Products 36 From the Research Chair 56 Reviews 37 Across the Miles 37 The Inner Flute: A Transcript of 70 NFA Office, Coordinators, Music and Words Committee Chairs 43 Notes from Around the World 75 Index of Advertisers 20 FEATURES 20 Louis Fleury and the Early Life of Pierrot lunaire by Nancy Toff Front and center in new-music happenings of the early 1900s, Louis Fleury helped introduce Schönberg’s seminal work in Paris, London, and Italy. -

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Dromey, Christopher ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3275-4777 (2020) Stravinsky’s ear for instruments. In: Stravinsky in Context. Griffiths, Graham, ed. Composers in Context . Cambridge University Press, pp. 170-178. ISBN 9781108422192, e-ISBN 9781108381086, e-ISBN 9781108390262. [Book Section] (doi:10.1017/9781108381086.024) Final accepted version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/28757/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. -

KATHERINE BALCH, Composer LIST of COMPOSITIONS

KATHERINE BALCH, composer LIST OF COMPOSITIONS Instrumental - Large Ensemble Leaf Fabric for orchestra (15 minutes) (2017) (2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, 2 percussion, piano, harp, strings) Commissioned by Georg Haas for the Tokyo Symphony/ Suntory Summer Arts Festival Premiered by the Tokyo Symphony, conducted by Ilan Volkov, September 7, 2017 drift for orchestra (11 minutes) (2017) (3 flutes, 3 clarinets, 3 oboes, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, 3 percussion, harp, strings) Commissioned by the Albany Symphony Orchestra/ American Music Festival Premiered by the Albany Symphony Orchestra/ American Music Festival on June 3, 2017 Una Corda for prepared piano and ensemble (7.5 minutes) (2016) (Flute, clarinet, bassoon, trumpet, trombone, percussion, piano, strings (single or multiple)) Commissioned by LA Philharmonic National Composer’s Intesive/ wildUp Selected for performance by wildUp in Disney Hall for LAPhil’s Noon to Midnight Festival New Geometry arr. for large ensemble (9 minutes) (2015/arr. 2017) (Flute, clarinet, saxophone, horn, trombone, percussion, harp, piano, strings (single or multiple)) Arrangement commissioned by Contemporaneous Leaf Catalogue for orchestra (9 minutes) (2015) (2 flutes, 2 clarinets, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, timpani, 2 percussion, piano, harp, strings) Commissioned by the Yale Philharmonia American Composer’s Orchestra (Underwood Readings) Minnesota Orchestra (Composer’s Institute) -

Getting There2 W CM Obit.Indd

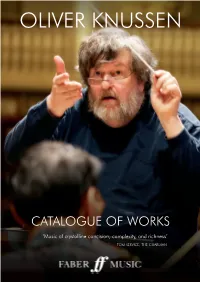

OLIVER KNUSSEN CATALOGUE OF WORKS ‘Music of crystalline concision, complexity, and richness’ TOM SERVICE, THE GUARDIAN OLIVER KNUSSEN 1952–2018 Abbreviations WOODWIND picc piccolo fl flute Oliver Knussen was a towering figure in contemporary music, as composer and conductor, afl alto flute teacher and artistic director. The relatively small size of his compositional output conceals bfl bass flute ob oboe music of exceptional refinement and subtlety – few bars of Knussen may have more impact bob bass oboe than whole movements by lesser composers. Besides definitive interpretations of his own ca cor anglais music he must surely have given more first performances than any other conductor, alongside acl alto clarinet E¨cl clarinet (E¨) an outstanding body of recordings. He was the central focus of so many activities, and an cl clarinet irreplaceable mentor to his fellow composers, who constantly sought and relied on his advice bcl bass clarinet and encouragement. cbcl contra bass clarinet bsn bassoon cbsn contra bassoon He was born in Glasgow; his father Stuart Knussen was principal double bass of the London ssax soprano saxophone Symphony Orchestra for nearly 20 years. Although he would have laughed at any idea of his asax alto saxophone tsax tenor saxophone being a child prodigy this gave him an unrivalled insight into the workings of the orchestra bsax baritone saxophone from an early age. It culminated in his conducting his First Symphony with the LSO at the BRASS age of 15, when their principal conductor István Kertész fell ill. His father played in the first hn horn performance of Benjamin Britten’s church parable Curlew River in 1964. -

Thomas B. Yee [email protected]

Thomas B. Yee [email protected] www.thomasbyee.com EDUCATION: The University of Texas at Austin Austin, TX D.M.A. Music Composition w/Music Theory Emphasis Expected May 2020 M.M. Music Composition w/Music Theory Emphasis (summa cum laude) August 2015 - May 2017 Pepperdine University Malibu, CA B.A. Music Composition & B.A. Creative Writing (summa cum laude) August 2010 – April 2014 SELECTED EXPERIENCE: University of Texas at Austin School of Design and Creative Technologies Austin, TX Supervising Teaching Assistant August 2015 – Present AET 304 — Foundations of Art and Entertainment Technologies • Teach 1-5 class lectures per semester on topics relevant to the intersection of Art and Entertainment Technologies • Design pedagogy and assessment for innovative class in online format via broadcast recording studio • Facilitate in-class activities through online pedagogy tools including discussion, Q&A, quizzes, and exams • Manage a team of 6 TAs to facilitate grading and discussion for the class of 500+ undergraduate students Stimmüng (TV Commercial Music Composition Studio) Santa Monica, CA Music Library Intern, Composer, Music Copyist May 2014 – December 2014 • Managed metadata entry for forthcoming music library of 7,000+ tracks in Soundminer • Composed 46 demo tracks (30+ minutes total) on 15 commercials for 12 clients up to Fortune 100 including Disney, Nike, Canon, Lockheed Martin, Volvo, the U.S. Army, and Mercedes • Created 7 scores, edited 3 scores, and created 25+ parts using Finale for 4 professional studio sessions -

Kyong Mee Choi • Dma

KYONG MEE CHOI • DMA Professor of Music Composition | Head of Music Composition Chicago College of Performing Arts | Roosevelt University 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60605, AUD 950 Email: [email protected]/Phone: 312-322-7137 (O)/ 773-910-7157 (C)/ 773-728-7918 (H) Website: http://www.kyongmeechoi.com Home Address: 6123 N. Paulina St. Chicago, IL 60660, U.S.A. 1. EDUCATION • University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, U.S.A. Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Composition/Theory, 2005 Dissertation Composition: Gestural Trajectory for Two Pianos and Percussion Dissertation Title: Spatial Relationships in Electro-Acoustic Music and Painting • Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, U.S.A. Master of Arts in Music Composition, 1999 • Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Completed Course Work in Master Study in Korean Literature majoring in Poetry, 1997 • Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea Bachelor of Science in Science Education majoring in Chemistry, 1995 PRINCIPAL STUDY • Composition: William Brooks, Agostino Di Scipio, Guy Garnett, Erik Lund, Robert Thompson, Scott Wyatt • Lessons and Master Classes: Coriun Aharonian, Larry Austin, George Crumb, James Dashow, Mario Davidovsky, Nickitas Demos, Orlando Jacinto Garcia, Vinko Globokar, Tristan Murail, Russell Pinkston, David Rosenboom, Joseph Butch Rovan, Frederic Rzewski, Kaija Saariaho, Stuart Smith, Morton Subotnick, Chen Yi • Music Software Programming and Electro-Acoustic Music: Guy Garnett (Max/MSP), Rick Taube (Common music/CLM/Lisp), Robert Thompson (CSound/Max),