Queer Identities and Glee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 1997 The Wonderful Wizards Behind the Oz Wizard Susan Wolstenholme Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wolstenholme, Susan. "The Wonderful Wizards behind the Oz Wizard," The Courier 1997: 89-104. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII· 1997 SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES COURIER VOLUME XXXII 1997 Ivan Mestrovic in Syracuse, 1947-1955 By David Tatham, Professor ofFine Arts 5 Syracuse University In 1947 Chancellor William P. Tolley brought the great Croatian sculptor to Syracuse University as artist-in-residence and professor ofsculpture. Tatham discusses the his torical antecedents and the significance, for Mdtrovic and the University, ofthat eight-and-a-half-year association. Declaration ofIndependence: Mary Colum as Autobiographer By Sanford Sternlicht, Professor ofEnglish 25 Syracuse University Sternlicht describes the struggles ofMary Colum, as a woman and a writer, to achieve equality in the male-dominated literary worlds ofIreland and America. A CharlesJackson Diptych ByJohn W Crowley, Professor ofEnglish 35 Syracuse University In writings about homosexuality and alcoholism, CharlesJackson, author ofThe Lost TtVeekend, seems to have drawn on an experience he had as a freshman at Syracuse University. Mter discussingJackson's troubled life, Crowley introduces Marty Mann, founder ofthe National Council on Alcoholism. Among her papers Crowley found a CharlesJackson teleplay, about an alcoholic woman, that is here published for the first time. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism by Rachael Horowitz Television, As a Cultural Expression, Is Uniqu

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism By Rachael Horowitz Television, as a cultural expression, is unique in that it enjoys relatively few boundaries in terms of who receives its messages. Few other art forms share television's ability to cross racial, class and cultural divisions. As an expression of social interactions and social change, social norms and social deviations, television's widespread impact on the true “general public” is unparalleled. For these reasons, the cultural power of television is undeniable. It stands as one of the few unifying experiences for Americans. John Fiske's Media Matters discusses the role of race and gender in US politics, and more specifically, how these issues are informed by the media. He writes, “Television often acts like a relay station: it rarely originates topics of public interest (though it may repress them); rather, what it does is give them high visibility, energize them, and direct or redirect their general orientation before relaying them out again into public circulation.” 1 This process occurred with the topic of feminism, and is exemplified by the most iconic females of recent television history. TV women inevitably represent a strain of diluted feminism. As with any serious subject matter packaged for mass consumption, certain shortcuts emerge that diminish and simplify the original message. In turn, what viewers do see is that much more significant. What the TV writers choose to show people undoubtedly has a significant impact on the understanding of American female identity. In Where the Girls Are , Susan Douglas emphasizes the effect popular culture has on American girls. -

Comedy Taken Seriously the Mafia’S Ties to a Murder

MONDAY Beauty and the Beast www.annistonstar.com/tv The series returns with an all-new episode that finds Vincent (Jay Ryan) being TVstar arrested for May 30 - June 5, 2014 murder. 8 p.m. on The CW TUESDAY Celebrity Wife Swap Rock prince Dweezil Zappa trades his mate for the spouse of a former MLB outfielder. 9 p.m. on ABC THURSDAY Elementary Watson (Lucy Liu) and Holmes launch an investigation into Comedy Taken Seriously the mafia’s ties to a murder. J.B. Smoove is the dynamic new host of NBC’s 9:01 p.m. on CBS standup comedy competition “Last Comic Standing,” airing Mondays at 7 p.m. Get the deal of a lifetime for Home Phone Service. * $ Cable ONE is #1 in customer satisfaction for home phone.* /mo Talk about value! $25 a month for life for Cable ONE Phone. Now you’ve got unlimited local calling and FREE 25 long distance in the continental U.S. All with no contract and a 30-Day Money-Back Guarantee. It’s the best FOR LIFE deal on the most reliable phone service. $25 a month for life. Don’t wait! 1-855-CABLE-ONE cableone.net *Limited Time Offer. Promotional rate quoted good for eligible residential New Customers. Existing customers may lose current discounts by subscribing to this offer. Changes to customer’s pre-existing services initiated by customer during the promotional period may void Phone offer discount. Offer cannot be combined with any other discounts or promotions and excludes taxes, fees and any equipment charges. -

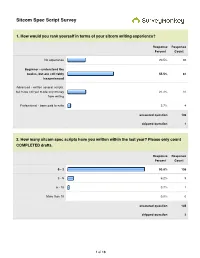

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for Artistic Achievement

Saluting Cheyenne Jackson for artistic achievement WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson is a native of the Pacific Northwest who has shown that even through adversity and hardship, one can make their dreams come true; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in films such as the Academy Award nominated United 93, the Sundance selected Price Check, and The Green; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has also appeared on television programs such as Glee, Ugly Betty, Curb Your Enthusiasm, and 30 Rock; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has appeared in such Broadway and off-Broadway productions as All Shook Up, The Agony and The Agony, The Heart of the Matter, and 8; and WHEREAS, Cheyenne Jackson has recorded two studio albums and has sold out Carnegie Hall twice; and WHEREAS, his work on Broadway, on television, in film and his activism on behalf of the LGBT community through his work with the Foundation for AIDS research and the Hetrick-Martin Institute which supports LGBT youth have been a source of inspiration for many in our community; and WHEREAS, we are proud to welcome Cheyenne Jackson back to the Pacific Northwest for his performance at Martin Woldson Theater in the hopes that his work will inspire many more; NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED, by the Spokane City Council that we hereby salute Cheyenne Jackson for all of his accomplishments and look forward to his performance with the Spokane Symphony. I, Ben Stuckart, Spokane City Council President, do hereunto set my hand and cause the seal of the City of Spokane to be affixed this 19th day of May in 2014 Ben Stuckart Spokane City Council President . -

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club

A Brief History of the Morehouse College Glee Club The Morehouse College Glee Club is the premier singing organization of Morehouse College, traveling all over the country and the world, demonstrating excellence not only in choral performance but also in discipline, dedication, and brotherhood. Through its tradition the Glee Club has an impressive history and seeks to secure its future through even greater accomplishments, continuing in this tradition through the dedication and commitment of its members and the leadership that its directors have provided throughout the years. It is the mission of the Morehouse College Glee Club to maintain a high standard of musical excellence. In 1911, Morehouse College, then under the name of Atlanta Baptist College, had a music professor named Georgia Starr. She served the College from 1903-1905 and again from 1908- 1911. Mr. Kemper Harreld, who officially founded the Morehouse College Glee Club, assumed leadership when he joined the College’s music faculty in the fall of 1911. Mr. Harreld became both, Chair of the Music Department and Director of the Glee Club. After faithfully serving for forty-two years, he retired in 1953. Mr. Harreld was responsible for beginning the Glee Club’s strong legacy of excellence that has since been passed down to all members of the organization. The Glee Club’s history continues in 1953 with the second director, Wendell Phillips Whalum, Sr., '52. Dr. Whalum was a prized student of Kemper Harreld. He served as Student Director during his tenure in the Glee Club. Dr. Whalum, was more commonly known as "Doc", and served Morehouse College and the Glee Club with the continued tradition of excellence through expanded repertoire and national and international exposure throughout his tenure at the College. -

Gleeks Rejoice! Alex Newell to Perform with Boston Gay Men's

Gleeks Rejoice! Alex Newell to Perform with Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Courtesy of Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Just in time for Pride, Boston Gay Men’s Chorus will perform “Can’t Stop the Beat,” the biggest production in its 32-year history, on June 12, 13, and 15 at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall. The concerts feature Alex Newell who stars as the show-stopping transgender teen Wade “Unique” Adams on FOX’s hit series Glee. Newell will also share the stage with the Chorus June 7 in his hometown of Lynn for a special Outreach Concert at Lynn Auditorium, part of the Chorus’s mission of community engagement. Proceeds from the concert will be donated to 13 LGBT-related and North Shore nonprofits (AIDS Action Committee, Children's Law Center of MA, Boys and Girls Club of Lynn, Cerebral Palsy of Eastern MA, Family & Children's Services, Girls, Inc., YMCA of Metro North, Gregg Neighborhood House, Straight Ahead Ministries, Mass. Coalition for the Homeless, RAW Artworks, Catholic Charities North, and Camp Fire of the North Shore). In this Q&A, Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Music Director Reuben M. Reynolds III takes us through the show! Q: Collaborating with Alex Newell sounds pretty exciting. What can audiences expect? A: Alex has such an amazing story. He’s from Lynn and he competed on a TV show called The Glee Project. As one of the winners he was cast in an episode of Glee. Well, everyone loved him so much he’s now a regular cast member. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAY CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 16 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2020 $NOT HS 23 BILLY STRINGS BG 1 CONRO DA 24 FLEETWOOD MAC B200 60, 182; INT 14; SIERRA HULL BG 6 ADAM LAMBERT RO 46 THE 1975 MO 17; RKA 25; RO 16, 38 BLACKBEAR A40 37; H100 43; HA 26; RO 48 BRADLEY COOPER B200 167; STX 6 PCA 5 SAM HUNT B200 28; CA 5, 35; CS 9, 10; H100 MIRANDA LAMBERT CA 31; CS 12, 15; H100 220 KID DA 10; DES 48 BLACKPINK WM 10 BOB CORRITORE BL 14 FLIPP -

Hearing Voices

January 4 - 10, 2020 www.southernheatingandac.biz/ Hearing $10.00 OFF voices any service call one per customer. Jane Levy stars in “Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist” 910-738-70002105-A EAST ELIZABETHTOWN RD CARDINAL HEART AND VASCULAR PLLC Suriya Jayawardena MD. FACC. FSCAI Board Certified Physician Heart Disease, Leg Pain due to poor circulation, Varicose Veins, Obesity, Erectile Dysfunction and Allergy clinic. All insurances accepted. Same week appointments. Friendly Staff. Testing done in the same office. Plan for Healthy Life Style 4380 Fayetteville Rd. • Lumberton, NC 28358 Tele: 919-718-0414 • Fax: 919-718-0280 • Hours of Operation: 8am-5pm Monday-Friday Page 2 — Saturday, January 4, 2020 — The Robesonian A penny for your songs: ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist’ premieres on NBC By Sachi Kameishi like “Glee” and “Crazy Ex-Girl- narrates the first trailer for the One second, Zoey’s having a ters who transition from dialogue chance to hear others’ innermost TV Media friend” and a stream of live-ac- show, “... what she got, was so regular conversation with her to song as though it were noth- thoughts through music, a lan- tion Disney remakes have much more.” best friend, Max, played by Skylar ing? Taking it at face value, peo- guage as universal as they come f you’d told me a few years ago brought the genre back into the In an event not unlike your Astin (“Pitch Perfect,” 2012). ple singing and dancing out of — a gift curious in that it sends Ithat musicals would be this cul- limelight, and its rebirth spans standard superhero origin story, Next thing she knows, he’s sing- nowhere is very off-putting and her on a journey that doesn’t nec- turally relevant in 2020, I would film, television, theater and pod- an MRI scan gone wrong leaves ing and dancing to the Jonas absurd, right? Well, “Zoey’s Ex- essarily highlight her own voice have been skeptical. -

Stereotypes in New Nordic Branding Journal of Place Management and Development

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Journal of Place Management and Development. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Sataøen, H L. [Year unknown!] “Exotic, welcoming and fresh”: stereotypes in new Nordic branding Journal of Place Management and Development https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-12-2019-0107 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:oru:diva-90359 The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1753-8335.htm “ ” New Nordic Exotic, welcoming and fresh : branding stereotypes in new Nordic branding Hogne Lerøy Sataøen School of Humanities, Education and Social Sciences, Örebro Universitet, Örebro, Sweden Received 10 December 2019 Revised 19 May 2020 31 August 2020 16 October 2020 7 January 2021 Abstract Accepted 26 January 2021 Purpose – Ideas related to “the Nordic” are important in the reconstruction of national identities in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and these countries’ modern national narratives are structurally highly similar. At the same time, there are clear differences between the Nordic countries regarding their national images. The purpose of this study is to a examine the relationship between ideas of the Nordic and national images through a qualitative study of brand manifestations on Nordic web portals for foreign visitors. Design/methodology/approach – The two guiding research questions are: How do Nordic branding strategies and national stereotypes impact on nation-branding content toward visitors in the Nordic region? What traces of the Nordic as a supranational concept can be found when the Nordic is translated into concrete national brand manifestations? The analysis focuses on brand manifestations such as brand visions, codes of expression, differentiation, narrative identity and ideologies. -

Ingham County Board of Commissioners June 13, 2017 Regular Meeting – 6:30 P.M

INGHAM COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS JUNE 13, 2017 REGULAR MEETING – 6:30 P.M. COMMISSIONERS ROOM, COURTHOUSE MASON, MICHIGAN AGENDA I. CALL TO ORDER II. ROLL CALL III. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE IV. TIME FOR MEDITATION V. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES FROM MAY 23, 2017 VI. ADDITIONS TO THE AGENDA VII. PETITIONS AND COMMUNICATIONS 1. A NOTICE OF A SECOND PUBLIC HEARING FOR THE CITY OF EAST LANSING TO APPROVE BROWNFIELD PLAN #24 FOR THE CITY CENTER DISTRICT PROPERTY LOCATED AT 125, 133, 135 AND 201-209 E. GRAND RIVER AVENUE AND 200 ALBERT AVENUE VIII. LIMITED PUBLIC COMMENT IX. CLARIFICATION/INFORMATION PROVIDED BY COMMITTEE CHAIR X. CONSIDERATION OF CONSENT AGENDA XI. COMMITTEE REPORTS AND RESOLUTIONS 2. RESOLUTION DESIGNATING THE MONTH OF JUNE, 2017 AS LGBTQ PRIDE MONTH IN INGHAM COUNTY 3. COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE – RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING AUDREY GERBER AS THE FIRST PLACE WINNER OF THE 2017 INGHAM COUNTY WOMEN’S COMMISSION DORIS CARLICE ESSAY CONTEST 4. COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE – RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING RACHEL SCOTT AS THE SECOND PLACE WINNER OF THE 2017 INGHAM COUNTY WOMEN’S COMMISSION DORIS CARLICE ESSAY CONTEST 5. COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE – RESOLUTION RECOGNIZING BRITTANY PIERCE AS THE THIRD PLACE WINNER OF THE 2017 INGHAM COUNTY WOMEN’S COMMISSION DORIS CARLICE ESSAY CONTEST 6. COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE – RESOLUTION TO ADOPT A POLICY FOR SETTLEMENT OF CLAIMS, LITIGATION AND SEPARATION AGREEMENTS 7. COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE – RESOLUTION TO APPROVE THE SPECIAL AND ROUTINE PERMITS FOR THE INGHAM COUNTY ROAD DEPARTMENT 8. COUNTY SERVICES AND FINANCE COMMITTEES – RESOLUTION APPROVING A SEPARATION AGREEMENT AND WAIVER OF CLAIMS WITH UNITED AUTOMOBILE AEROSPACE AND AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENT WORKERS OF AMERICA (UAW-TOPS) 9.