Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism by Rachael Horowitz Television, As a Cultural Expression, Is Uniqu

Mary, Roseanne, and Carrie: Television and Fictional Feminism By Rachael Horowitz Television, as a cultural expression, is unique in that it enjoys relatively few boundaries in terms of who receives its messages. Few other art forms share television's ability to cross racial, class and cultural divisions. As an expression of social interactions and social change, social norms and social deviations, television's widespread impact on the true “general public” is unparalleled. For these reasons, the cultural power of television is undeniable. It stands as one of the few unifying experiences for Americans. John Fiske's Media Matters discusses the role of race and gender in US politics, and more specifically, how these issues are informed by the media. He writes, “Television often acts like a relay station: it rarely originates topics of public interest (though it may repress them); rather, what it does is give them high visibility, energize them, and direct or redirect their general orientation before relaying them out again into public circulation.” 1 This process occurred with the topic of feminism, and is exemplified by the most iconic females of recent television history. TV women inevitably represent a strain of diluted feminism. As with any serious subject matter packaged for mass consumption, certain shortcuts emerge that diminish and simplify the original message. In turn, what viewers do see is that much more significant. What the TV writers choose to show people undoubtedly has a significant impact on the understanding of American female identity. In Where the Girls Are , Susan Douglas emphasizes the effect popular culture has on American girls. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

Privatization in Russia: Catalyst for the Elite

PRIVATIZATION IN RUSSIA: CATALYST FOR THE ELITE VIRGINIE COULLOUDON During the fall of 1997, the Russian press exposed a corruption scandal in- volving First Deputy Prime Minister Anatoli Chubais, and several other high- ranking officials of the Russian government.' In a familiar scenario, news organizations run by several bankers involved in the privatization process published compromising material that prompted the dismissal of the politi- 2 cians on bribery charges. The main significance of the so-called "Chubais affair" is not that it pro- vides further evidence of corruption in Russia. Rather, it underscores the im- portance of the scandal's timing in light of the prevailing economic environment and privatization policy. It shows how deliberate this political campaign was in removing a rival on the eve of the privatization of Rosneft, Russia's only remaining state-owned oil and gas company. The history of privatization in Russia is riddled with scandals, revealing the critical nature of the struggle for state funding in Russia today. At stake is influence over defining the rules of the political game. The aim of this article is to demonstrate how privatization in Russia gave birth to an oligarchic re- gime and how, paradoxically, it would eventually destroy that very oligar- chy. This article intends to study how privatization influenced the creation of the present elite structure and how it may further transform Russian decision making in the foreseeable future. Privatization is generally seen as a prerequisite to a market economy, which in turn is considered a sine qua non to establishing a democratic regime. But some Russian analysts and political leaders disagree with this approach. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

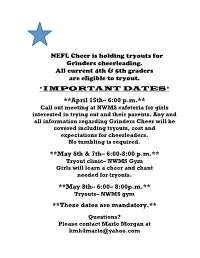

NEFL Grinders Cheer

NEFL Cheer is holding tryouts for Grinders cheerleading. All current 4th & 5th graders are eligible to tryout. *IMPORTANT DATES* **April 15th– 6:00 p.m.** Call out meeting at NWMS cafeteria for girls interested in trying out and their parents. Any and all information regarding Grinders Cheer will be covered including tryouts, cost and expectations for cheerleaders. No tumbling is required. **May 6th & 7th– 6:00-8:00 p.m.** Tryout clinic– NWMS Gym Girls will learn a cheer and chant needed for tryouts. **May 8th– 6:00– 8:00p.m.** Tryouts– NWMS gym **These dates are mandatory.** Questions? Please contact Marlo Morgan at [email protected] NEFL Grinders Cheer The tryouts for NEFL Grinders cheer will be held May 5th-7th from 6:00-8:00 in the upper gym at NWMS. The girls need to wear a t-shirt/tank, shorts, tennis shoes and have their hair pulled back. They should bring a water bottle with them. The first two nights will be the clinic where the girls will learn the cheer and chant needed for the tryouts. The third night will be the tryouts. Parents are welcome to stay in the gym and watch the clinic, but the tryouts are closed. The team will be announced that night after tryouts. All girls must be registered with NEFL before they will be allowed to tryout. You can register online at www.nefl.net. Please bring your printed receipt of registration on the first day of cheer clinic. ************************************************************************ The girls will be judged on a 1-5 scale on the following skills: -Cheer and chant memory -Motions -Voice projection -Enthusiasm -Jumps -Attitude -Tumbling will be scored as follows: -Cartwheel -1 point -Round Off - 2 points -Back Handspring - 3 points -Back Handspring series - 4 points -Tuck – 5 points The cost for participating in Grinders cheer is approximately $325-$350. -

Russia: CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 to FEBRUARY 1995

Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... Français Home Contact Us Help Search canada.gc.ca Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets Home Issue Paper RUSSIA CHRONOLOGY DECEMBER 1993 TO FEBRUARY 1995 July 1995 Disclaimer This document was prepared by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada on the basis of publicly available information, analysis and comment. All sources are cited. This document is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed or conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. For further information on current developments, please contact the Research Directorate. Table of Contents GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures Political Leaders 1. INTRODUCTION 2. CHRONOLOGY 1993 1994 1995 3. APPENDICES TABLE 1: SEAT DISTRIBUTION IN THE STATE DUMA TABLE 2: REPUBLICS AND REGIONS OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION MAP 1: RUSSIA 1 of 58 9/17/2013 9:13 AM Issue Papers, Extended Responses and Country Fact Sheets file:///C:/Documents and Settings/brendelt/Desktop/temp rir/CHRONO... MAP 2: THE NORTH CAUCASUS NOTES ON SELECTED SOURCES REFERENCES GLOSSARY Political Organizations and Government Structures [This glossary is included for easy reference to organizations which either appear more than once in the text of the chronology or which are known to have been formed in the period covered by the chronology. The list is not exhaustive.] All-Russia Democratic Alternative Party. Established in February 1995 by Grigorii Yavlinsky.( OMRI 15 Feb. -

January 2020

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 January 2020 Decade in Review! With the decade coming to a close a few weeks ago, the editorial staff decided that we should fl ashback to the ideas and moments that shaped the decade. As we adjust to life in the new “roaring twenties,” here is a breakdown of the most prominent events of each year from the past decade. 2010: On January 12, an earthquake registering a magnitude 7.0 on the Richter scale struck Haiti, causing about 250,000 deaths and 300,000 injuries. On March 23, the Aff ordable Care Act is signed into law by Barack Obama. Commonly referred to as “Obamacare,” it was considered one of the most extensive health care reform acts since Medicare, which was passed in 1965. On April 20, a Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded over the Gulf of Mexico. Killing eleven people, it is considered one of the worst oil spills in history and the largest in US waters. On July 25, Wikileaks, an organization that allows people to anonymously leak classifi ed information, released more than 90,000 documents related to the Afghanistan War. It is oft en referred to as the largest leak of classifi ed information since the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. Th e New Orleans Saints won their fi rst Super Bowl since Hurricane Katrina, LeBron James made his way to Miami, Kobe Bryant won his fi nal title, and Butler went on a Cinderella run to the NCAA Championship. Th e year fi ttingly set the tone for a decade of player empowerment and underdog victories. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Andrew Goldberg's

ANDREW GOLDBERG Emmy Award-winning investigate producer/director Andrew Goldberg is the founder and owner of Two Cats Productions in New York City. In this capacity he has Executive Produced and Directed 13 Prime- Time documentary specials for PBS and Public Television, two broadcast series (spanning 39 episodes) for HGTV and DIY, and countless long and short-form segments for such outlets as CBS News Sunday Morning, ABC News, National Public Radio, E! Entertainment Television, Food Network, and FYI. He has worked with and/or interviewed more celebrities than he can remember including Ed Harris, Former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, Maya Angelou, Michael Douglas, Natalie Portman, Itzhak Perlman, Julianna Margulies, Senator Joseph Lieberman, Shaquille O’Neal, Senator Bob Dole, The President of Armenia (random but true), Julianne Moore, Yo-Yo Ma, Elliot Gould, Olympia Dukakis, Pierce Brosnan, Edie Falco, Kristen Bell, Laura Linney, the legendary Walter Cronkite… and many more. Andrew is currently directing two films including a fully funded, feature documentary, currently in post- production, that explores the complex relationship between humans and animals. The film questions how animals are both respected in the world but also used for food, science, textiles and entertainment. He is also in post-production on two hour documentary that takes a look at the resurgence in anti- Semitism in the world today. Some of other previous films include: The Armenian Genocide which received extraordinary reviews and coverage in almost every major newspaper in the US including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The Boston Globe. -

'The Mystery Cruise' Cast Bios Gail O'grady

‘THE MYSTERY CRUISE’ CAST BIOS GAIL O’GRADY (Alvirah Meehan) – Multiple Emmy® nominee Gail O'Grady has starred in every genre of entertainment, including feature films, television movies, miniseries and series television. Her most recent television credits include the CW series “Hellcats” as well as "Desperate Housewives" as a married woman having an affair with the teenaged son of Felicity Huffman's character. On "Boston Legal," her multi-episode arc as the sexy and beautiful Judge Gloria Weldon, James Spader's love interest and sometime nemesis, garnered much praise. Starring series roles include the Kevin Williamson/CW drama series "Hidden Palms," which starred O'Grady as Karen Miller, a woman tormented by guilt over her first husband's suicide and her son's subsequent turn to alcohol. Prior to that, she starred as Helen Pryor in the critically acclaimed NBC series "American Dreams." But O'Grady will always be remembered as the warm-hearted secretary Donna Abandando on the series "NYPD Blue," for which she received three Emmy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress in a Dramatic Series. O'Grady has made guest appearances on some of television's most acclaimed series, including "Cheers," "Designing Women," "Ally McBeal" and "China Beach." She has also appeared in numerous television movies and miniseries including Hallmark Channel's "All I Want for Christmas" and “After the Fall” and Lifetime's "While Children Sleep" and "Sex and the Single Mom," which was so highly rated that it spawned a sequel in which she also starred. Other television credits include “Major Crimes,” “Castle,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “Necessary Roughness,” “Drop Dead Diva,” “Ghost Whisperer,” “Law & Order: SVU,” “CSI: Miami,” "The Mentalist," "Vegas," "CSI," "Two and a Half Men," "Monk," "Two of Hearts," "Nothing Lasts Forever" and "Billionaire Boys Club." In the feature film arena, O'Grady has worked with some of the industry's most respected directors, including John Landis, John Hughes and Carl Reiner and has starred with several acting legends. -

US Views on a Permanent International Criminal Court

The Quivering Gulliver: U.S. Views on a Permanent International Criminal Court JOHN F. MURPHY* I. Introduction As noted by other contributors to this symposium, the United States found itself among a small minority of strange bedfellows when it voted against the draft statute for a permanent international criminal court adopted by the United Nations-sponsored conference in Rome, Italy on July 17, 1998.1 The U.S. vote against the Rome Statute stands in sharp contrast to strong statements of support for a permanent international criminal court by President Clinton and other members of his administration.2 At first blush one is inclined to explain away this discrepancy by focusing on U.S. objections to specific provisions of the Rome Statute. If particular provisions of the Rome Statute are the basis for U.S. opposition, then one could expect that the problem could be resolved by amending the statute. It is the premise of this article, however, that the basic problem is more profound. In this writer's opinion, current U.S. views on the role of the United States in foreign affairs and on international law and international institutions ensured that when the final moment of decision arrived, the United States would be unable to support the establishment of a permanent international criminal court not subject to the control of the United States. Moreover, these U.S. views pose problems that greatly transcend the issue of whether to support a permanent international criminal court. They call into question the willingness of the United States to adhere to the rule of law in international affairs-a concept that U.S. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page