Hatching a Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backyard June/July 2018

Volume 13, Number 3 Backyard June/July 2018 PoultryAmerica's Favorite Poultry Magazine HELP YOUR CHICKENS maintain a healthy digestive system DIY COOP WATERING with rainwater TIPS TO KEEP YOUR CHICKENS HAPPY while you're on vacation PatrioticHISTORY & Poultry: BREEDS $5.99 U.S. www.countrysidenetwork.com PLUS: CHICKEN CAESAR SALAD, make classic or pesto Backyard Poultry FP 6-16 THINK:Mother Earth 4.5 x7 6/30/16 3:51 PM Page 1 SATISFACTION $ 95 19 EACH –––––––––––––– FREE SHIPPING GUARANTEED When you buy 4 lights or more oryourmoney –––––––––––––– back! PROMO CODE 4FREE To Protect Your Property From Night Predator Animals Nite•Guard Solar® has been proven effective in repelling predator animals for the past 19 years. #1 Nite•Guard Solar attacks the deepest most primal The World’s fear of night animals, that of being discovered. Top Selling Solar Powered Nite•Guard When the sun goes down, Nite•Guard begins to Security System Repellent Tape DON’T BE FOOLED BY Keeps predators flash and continues until sunrise. The simple away during the but effective fact is that a “flash of light” is COPY CATS daylight hours sensed as an eye and becomes an immediate $ 95 14 Per Roll threat to the most ferocious night animals and they will run away. PO Box 274 • Princeton MN 55371 • 1.800.328.6647 ......................... For information and videos, see us at FAMILY OWNED AND OPERATED SINCE 1997 www.niteguard.com ......................... Backyard Poultry FP 6-16 THINK:Mother Earth 4.5 x7 6/30/16 3:51 PM Page 1 SATISFACTION $ 95 19 EACH –––––––––––––– FREE SHIPPING GUARANTEED When you buy 4 lights or more oryourmoney –––––––––––––– back! PROMO CODE 4FREE To Protect Your Property From Night Predator Animals Nite•Guard Solar® has been proven effective in repelling predator animals for the past 19 years. -

Classic Menu

classic menu starters Home cured salmon with crème fraîche, caviar and dill oil Brawn terrine with celeriac remoulade and piccalilli dressing and curly endive Spiced foie gras and ham hock boudin with Sauternes poached golden sultanas and truffled brioche **£2.50 Ox tongue fritter with horseradish cream, pickled carrots and micro leaf salad Cured Cornish scallops with pickled vegetables, avocado purée and micro cress salad **£3.00 Potted Aylesbury duck with confit orange pickled shallots and pecan salad Tian of Cornish crab with brown crab mayo, avocado, bread wafers and shoots Heritage beetroot with Cerney goats’ cheese, pickle liquor and onion ash (V) main courses Roast rump of Cotswold lamb with carrot purée, rösti potato, braised cabbage, roasted turnips and rosemary jus Fillet of native Shorthorn beef with shallot purée, treacle cured ox cheek, fondant potato and wilted greens **£5.00 Roasted Cornish halibut with braised gem lettuce, confit potatoes and a caviar sauce Confit Tamworth pork belly with apple purée, black pudding mash, greens and a cider sauce Seabass with brown crab arancini, tomato sauce and braised fennel 24 hour braised Shorthorn beef feather blade with celeriac purée, Pommes Anna , buttered cabbage and bourguignon sauce Tamworth streaky bacon wrapped Cotswold white chicken with sweetcorn purée, potato rösti and chargrilled leeks Grilled plaice with sea vegetables, saffron potatoes and brown shrimp butter desserts Bitter Chocolate fondant with salted caramel ice cream Pistachio and raspberry mille-feuille Decedent chocolate brownie with poached cherries and crème fraîche Lemon meringue pie with raspberry coulis Blackcurrant and ginger cheesecake with blackcurrant sorbet Apple tart Tatin with vanilla ice cream Crème caramel with white chocolate and cardamom shortbread Baba au rhum with calvados poached apples, sultanas and crème anglaise Freshly brewed coffee, tea, fruit infusions & petit fours (Items with a ** are subject to a per head supplement). -

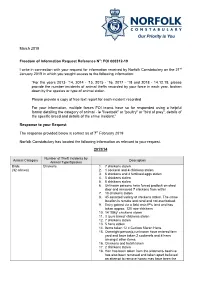

FOI 000312-19 I Write in Connection with Your Request for Information Re

March 2019 Freedom of Information Request Reference No: FOI 000312-19 I write in connection with your request for information received by Norfolk Constabulary on the 21st January 2019 in which you sought access to the following information: “For the years 2013- ‘14, 2014 - ‘15, 2015 - ‘16, 2017 - ‘18 and 2018 - 14.12.18, please provide the number incidents of animal thefts recorded by your force in each year, broken down by the species or type of animal stolen. Please provide a copy of free text report for each incident recorded. For your information, multiple forces FOI teams have so far responded using a helpful format detailing the category of animal - ie "livestock" or "poultry" or "bird of prey", details of the specific breed and details of the crime incident.” Response to your Request The response provided below is correct as of 7th February 2019 Norfolk Constabulary has located the following information as relevant to your request. 2013/14 Number of Theft Incidents by Animal Category Description Animal Type/Species Birds Chickens 1. 7 chickens stolen (32 crimes) 2. 1 cockerel and 4 chickens stolen 3. 6 chickens and 4 fertilised eggs stolen 4. 5 chickens stolen 5. 6 chickens stolen 6. Unknown persons have forced padlock on shed door and removed 7 chickens from within 7. 10 chickens stolen 8. 45 assorted variety of chickens stolen. The crime location is remote and rural and not overlooked. 9. Entry gained via a field onto IP's land and has taken approx. 120 rare chickens 10. 14 ‘Silky’ chickens stolen 11. -

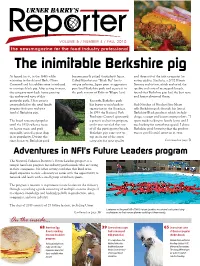

The Inimitable Berkshire Pig As Legend Has It, in the 1640S While Became Greatly Prized Throughout Japan

VOLUME 5 / NUMBER 4 / FALL 2010 the newsmagazine for the food industry professional Berkshire burger The inimitable Berkshire pig As legend has it, in the 1640s while became greatly prized throughout Japan. and three out of the four categories for wintering in the shire of Berk, Oliver Called Kurobata or “Black Pig” for its eating quality. Similarly, a 2002 Illinois Cromwell and his soldiers were introduced unique coloring, Japan grew to appreciate Sensory evaluation, which evaluated the to a unique black pig. After eating its meat, pure bred Berkshire pork and equate it to quality and taste of many pork breeds, the company went back home praising the pork version of Kobe or Wagyu beef. found that Berkshire pigs had the best taste the quality and taste of this and lowest abnormal flavor. particular pork. These praises Recently, Berkshire pork eventually led to the royal family has begun to gain back its Rob Nicolosi of Nicolosi Fine Meats keeping their own exclusive reputation in the Americas. sells Berkshire pork through his line of herd of Berkshire pigs. In 1995 the National Pork Berkshire Black products which include Producers Council sponsored chops, sausage and bacon among others. “I The breed remained popular a genetic evaluation program, spent weeks talking to family farms and I until the 1950s when a focus and it was revealed that out was looking for something special. I chose on leaner meat, and pork of all the participating breeds, Berkshire pork knowing that the product especially, caused a great drop Berkshire pigs came out on was so good I could invest in it, even in its popularity. -

Lawrie & Symington Ltd Forfar Mart

Lawrie & Symington Ltd Forfar Mart Sale of Poultry, Eggs & Sundries Thursday 2nd April 2015 At 11am In The Strathmore Hall PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS PLEASE REGISTER AND OBTAIN A BUYERS NUMBER CATALOGUE £2.00 48 John Street, Forfar DD8 3EZ Tel 01307 462651 Fax 01307 464290 www.lawrieandsymington.com CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Buyer’s commission of 10% will be added to each lot + VAT @ 20% on commission only 2. Lots (as per cage) will be sold in catalogue order commencing with birds at 11.00am 3. Reserve prices – All reserve prices will be adhered to and any lots failing to reach the reserve price will be passed as unsold An upset price of £5.00 will apply to each lot (eggs £1.00). If the upset price is not reached the auctioneer will pass on to the next lot 4. Vendors are asked before leaving the premises please check with the office that all their entries are sold 5. All lots must be cleared from the market premises, 1 hour after conclusion of sale. Purchasers may not remove any lots without a pass. Vendors with unsold lots must also produce a pass which is obtainable from the office 6. Auctioneers or their staff shall not be in anyway responsible for any loss or damage caused prior to, during or after the sale 7. At the fall of the hammer the lot becomes sole responsibility of the successful bidder 8. All bidders should satisfy themselves to what it is they are buying. Forfar Mart holds no responsibility for any description given or birds being caged in wrong order 9. -

Pleasurable Poultry Keeping

) I.l:AvSUKABLb F .-^. I \tmAM^V^ Caution! Caution!! Caution!!! 4*7 BSllPyt '•'0 ^^^ WHOM IT MAY CONCEEN. C d H }N. T( i for Pc )n of "S or have ob osts. MEMORIAL POULTRY LIBRARY^^ g CORNELL al J. M. GWIN lrfcY»vvvvvvv^»VV»Y»v»Vv»S/«V' ra^niet on rouiTfy^Bearing ana samples oi Pood Post Free for One Stamp of SPRATTS PATENT, BERMONDSEf, LONDON, S.E. Cornell University Library SF 487.B871PI Pleasurable poultry keeping. 3 1924 003 154 469 FOUR GOLD MEDALS Have been awarded to the WESTMERIA COMPANY For their Poultry Appliances. WSAT IS SAID OF THEM: '* A cffmplete sjtcceag."—J)uche88 of Wellington. " Undoubtedlj/ the moat ^ffi^iient in the ma/rket"--K W. Webster, the noted poultry exhibitor. " They are pei'/ect."~IjtvAy John Hay. "Proved a decided swccesB."— H. Digby, Esq. author of " How to Make £50 a Year by Ducks;" "•TAc "best I know. All my hatch^ have hem gooi.''—ilr9: Godefroi. " All tliat can be deHred."'-J. Cooper Grarman, Esti. incubator, The 100 £gg £8 8s. " It Jiatched all the duck eggs put in."—Sir Fredk 50-£igg „ £6 6s. MuBgrave. FOREMOST EXHIBITORS aiVE 1KEU TBE BiaBEST FBAISE. "/( 18 the &esi."—Edward Brown, P.L.S., author of *'Have now discarded all others." — W. Cook, Esq " Poultry Keeping as an Industry." (originator of the Orpington Fowl). " Undoiihtedly the 6e«(."—H. Swithenbank, Esq. "Better than any other."—Geo. Brooka, Esq. " Mwih better than s."—Mrs. Macdowell. "Mv£h less troitble tftan hens, and they thrive better. " By far the best: ~H. -

Pubputsaylesburyduckbackonth

www.aylesburytoday.co.uk THE BUCKS HERALD WEDNESDAY, MAY 28, 2008 section 1 news 5 Dining �AND BRIEFLY.... Big drugs swoop PubputsAylesburyDuckbackonthemenu in Aylesbury DRUGS worth £15,000 were seized in a property in Legendary dish Aylesbury on Wednesday. At noon last week, police makes comeback went to a house on Eaton Road where they discovered a large Staff and amount of the class A drug, at Broad Leys pub, customers at cocaine. relaunch of A 22-year-old-man, named supplied by only the by police as Tristan Folaranmi, Aylesbury was arrested on suspicion of breeder in England Duck dish at possession with intent to Broad Leys supply and was charged and remanded on Saturday. by Anna Dowdeswell Photographs: A 45-year-old woman was Reporter Richard also arrested on suspicion of [email protected] Duggan possession of a class A drug 01296 619771 270508d02 with intent to supply but was released on bail until June 25. AYLESBURY Duck is back in town The arrest came as part of being served on a menu for the first last week’s National Tackling in and they remembered some of the Drugs Week and falls under time in about 50 years. breeders in Weston Turville. It has The Broad Leys on Wendover Operation Falcon, an initiative sparked off many conversations. from Thames Valley Police to Road is the only restaurant in People are chatting and telling others clear the streets of Aylesbury Aylesbury serving the legendary dish about it and that’s the best form of of drugs. with traditionally-bred ducks sup- promoting it.” Acting Chief Inspector, plied by the last remaining breeder of At its peak in the 1850s thousands Steve Williams, said: “A the bird, farmer Richard Waller. -

Starters from the Grill from the Sea from the Farm from the Field Side

GardenStarters pea and mint soup with crème fraiche £5.95 RoastedFrom Aylesbury the duckfarm breast on pan-fried carrot Roasted plum tomato soup with basil croute £5.95 polenta, sautéed spring greens and a caramelised raspberry jus £18.95 Roasted English beetroot salad: candy pink, golden and blood red varieties of beetroot with a goat’s cheese Chocolate rubbed BBQ pork fillet with an apricot and crotin, and peppered balsamic dressing £8.50 grain mustard warm potato salad, crisp apple stack and cider jus £20.95 Trio of salmon: salmon tartare, Loch Fyne whisky marinated smoked salmon, dill gravadlax, fennel and Orange and thyme crusted rack of Casterbridge lamb, cox’s orange pippin apple salad, honey and mustard potato gratin, spring vegetables and Grand Marnier jus. £22.95 crème fraiche £10.95 Shepherd’s pie with rich lamb gravy and peppered Watercress, poached pear and Stilton salad with a Savoy cabbage £16.95 walnut dressing £9.25 Braised cheek of beef with a herbed crust, horseradish Cornish crab falafel with beetroot hummus cream, asparagus, Chanteney carrots and port reduction £18.95 pomegranate & chilli salsa £9.95 Classic grilled breast of chicken Caesar ; baby gem, Farmhouse terrine: Gloucester Old Spot boar, rabbit shaved parmesan, ciabatta croutons, creamy Caesar and duck terrine with toasted sourdough bread and dressing and anchovies £15.95 Cumberland jelly £10.95 Pan seared Queen scallops on an Earl Grey tea £15.95 infused couscous, lemon buerre blanc, and micro FromPenne pasta the with tomato field sauce, chilli and Greek -

Aberdeen & Northern Marts

FOOD CHAIN INFORMATION Aberdeen & VETERINARY MEDICAL WITHDRAWALS From 1st January 2010 new legislation comes into force requiring Northern Marts slaughterhouse operators to receive, check and act upon food chain A member of ANM GROUP LTD. information. To comply with these new requirements we have modified our THAINSTONE CENTRE INVERURIE, AB51 5XZ movement documents for all classes of stock coming to market to include the necessary declarations on food chain information. This will allow us to pass Telephone : 01467 623710 on this information which must accompany all animals to slaughter and for Store Stock to pass on Medical withdrawal information. Unless otherwise stated at the time of sale (either by the auctioneer or on the CATALOGUE catalogue) all livestock are sold as having completed all withdrawal periods for any veterinary medicines they have received. For any animals under of treatment the details must be completed in the movement declaration form. ANNUAL SPECIAL SALE OF It is the responsibility of the buyer to ensure that any animal destined for the RARE & MINORITY BREEDS OF food chain are outwith any withdrawal periods. Please note all sheep will require two documents, the Scottish Government LIVESTOCK & POULTRY SAMU Movement Document and our Movement Document incorporating the Food Chain Information Declaration. within THAINSTONE CENTRE, INVERURIE New Livestock keepers: on Requirement to register with your Animal Health Office. th SATURDAY 7 MAY 2016 New keepers of the main livestock species (cattle, sheep, goats, pigs) are from 10.00 am required to register their herds and flocks, and the ‘‘holdings’’ they are kept on, under EU Directives. This applies to any number of animals, including individual ‘‘pets’’. -

Catalogue of 1029 Lots of POULTRY, BANTAMS, WILDFOWL, WATERFOWL, DEADSTOCK & HATCHING EGGS

Catalogue of 1029 Lots of POULTRY, BANTAMS, WILDFOWL, WATERFOWL, DEADSTOCK & HATCHING EGGS At SALISBURY LIVESTOCK MARKET Netherhampton Road Salisbury SP2 8RH (A3094 west of Salisbury) SATURDAY 19th SEPTEMBER 2015 Sale commences at 9 am sharp with the Deadstock Full Restaurant Facilities available Tel 01722 321215 Fax 01722 421553 Email [email protected] £2 NOTES The Market will open at 7 am and all the cages will be erected and numbered by this time. Vendors are therefore encouraged to arrive as early as possible, but should have their entries penned by 8.45 am. Once unloaded all vehicles should be removed from the unloading ramps and parked in an orderly fashion. A supply of wood shavings and water will be available but as usual Vendors must provide their own drinkers. Vendors are reminded that there is a maximum of 5 birds allowed in a pen (except pigeons or chicks). Also only 1 cockerel per cage (NOT A SINGLE COCKEREL). No extra cages will be allocated on the day. Abbreviations PR - 1 Hen and 1 Cockerel TRIO - 2 Hens and 1 Cockerel QUARTET - 3 Hens and 1 Cockerel QUINTET - 4 Hens and 1 Cockerel POL - Point of Lay PLEASE NOTE ALL BIRDS ARE 2015 HATCHED UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED. VENDORS ARE REQUESTED NOT TO PLACE ANY STRAW IN THE POULTRY OR BANTAM CAGES, SHAVINGS HOWEVER, ARE ACCEPTABLE. ALL PURCHASERS, AND VENDORS with any unsold lots, must collect their tickets from the Auctioneers Sales Office. They should then make their way to the cages, where their birds will be released by a Steward. All purchases must be paid for within an hour of the last lot being sold. -

Courses Courses Starters Galvin Classics Salad

Wheat bread and Glastonbury farmhouse butter 3.50 Nocellara olives in Hillfarm rapeseed oil 4.00 / Marcona almonds, marinated artichokes 4.00 Glass of Ayala Majeur Brut NV 14.75 STARTERS GALVIN CLASSICS SALAD & SOUP Dedham Vale beef ‘Steak Tartare’10.50/18.50 Rosanna onion & Dunkerton’s cider soup, Berkswell cheese 8.00 Belgian endive, walnut & Roquefort salad 8.00 Beech smoked chicken, mango & coriander dressing 7.00/13.50 Dressed Portland crab, Hampshire watercress & rye bread 15.50 Chargrilled autumnal vegetables, toasted grains & seeds 8.50/16.50 Galvin cured smoked salmon, Burford brown egg, sour cream & caviar 12.50 LOBSTER FROM THE GRILL Half or Whole 22.50/42.50 Rose County beef rib eye 28.00 Cumbrian bavette 22.00 Served with garlic butter, wild mushrooms & watercress Served with confit tomatoes, bone marrow, parsley & watercress Green peppercorn/ red wine/ horseradish butter 1.50 each MAIN COURSES PASTA & FISH COURSES MEAT Portland crab linguini, chilli & coriander 16.50/28.50 Galvin Deluxe Cumbrian beef burger & house relish* 17.00 Pavé of Peterhead halibut, dashi broth, wasabi & sea herbs 24.50 Herdwick Mutton T-bone steak, chickpeas, yoghurt & harissa 26.00 Harpooned Brixham plaice, brown shrimps, lemon, capers & brown butter 23.50 Roast Berkshire Pheasant, choucroute, mushroom & game broth* 19.50 Onion squash risotto, caramelised goat’s cheese & crispy sage 8.50/16.00 Haunch of Highland Venison, quince, black cabbage & chestnuts 24.50 PRIX FIXE SIDES Matchstick fries & spiced mayonnaise Deep fried whitebait & tartare sauce -

Here Will Be a £1.00 Supplement Per Person

MENUS chefs’ introduction Our food philosophy at Oxford Fine Dining is to offer our clients’ restaurant standard food in amazing and unique spaces. We source ingredients and design dishes to be of the highest quality, using classic techniques whilst also pushing ourselves to be at the very front of new cooking trends. Having formed great relationships with local suppliers, it means that we can work in a sustainable and ethical environment, using the very best ingredients, whilst leading the way in our profession and creating your food experience. My team and I have worked hard to create a balanced and varied menu, to help you on your journey to a wonderful and personal event. Sean Ducie Head Chef T: 01865 728240 [email protected] Unit 12 • Oddington Grange • Weston on the Green • OXON • OX25 3QW www.oxfordfinedining.co.uk DINING canapés HOT Photography Image: Jess Orchard Lamb belly lollypop with mint jelly (GF, DF) Quite possibly... Saffron arancini with paprika mayo (V) Cheddar cheese ploughman’s fritter (V) Oxford’s most exclusive Smoked hake with pea pureé and scraps (GF) Sticky slow cooked pork belly with crackling (GF,DF) private dining venue. Venison and smoked bacon Wellington Cauliflower cheese croquette (V) Mini Yorkshire pudding with treacle cured feather blade and grain mustard mayo COLD Cured mackerel with rhubarb and cucumber (GF, DF) Aged Parmesan mousse with sundried tomato (V) Whipped goats’ cheese with crisp beetroot and black olive caramel (V) Mexican spiced chicken with black bean hummus and pickled onions