Anthony Downs the Brookings Institution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No. 2646 Wednesday, March 20, 2013, 1:30 p.m. City Council Chamber One Technology Center – 175 E. 2nd Street, 2nd Floor Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Others Present Covey Stirling Bates Tohlen, COT Carnes Walker Fernandez VanValkenburgh, Legal Dix Huntsinger Warrick, COT Edwards Miller Leighty White Liotta Wilkerson Midget Perkins Shivel The notice and agenda of said meeting were posted in the Reception Area of the INCOG offices on Monday, March 18, 2013 at 2:10 p.m., posted in the Office of the City Clerk, as well as in the Office of the County Clerk. After declaring a quorum present, 1st Vice Chair Perkins called the meeting to order at 1:30 p.m. REPORTS: Director’s Report: Ms. Miller reported on the TMAPC Receipts for the month of February 2013. Ms. Miller submitted and explained the timeline for the general work program for 6th Street Infill Plan Amendments and Form-Based Code Revisions. Ms. Miller reported that the TMAPC website has been improved and should be online by next week. Mr. Miller further reported that there will be a work session on April 3, 2013 for the Eugene Field Small Area Plan immediately following the regular TMAPC meeting. * * * * * * * * * * * * 03:20:13:2646(1) CONSENT AGENDA All matters under "Consent" are considered by the Planning Commission to be routine and will be enacted by one motion. Any Planning Commission member may, however, remove an item by request. 1. LS-20582 (Lot-Split) (CD 3) – Location: Northwest corner of East Apache Street and North Florence Avenue (Continued from 3/6/2013) 1. -

Managing Metropolitan Growth: Reflections on the Twin Cities Experience

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE Ted Mondale and William Fulton A Case Study Prepared for: The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy © September 2003 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE BY TED MONDALE AND WILLIAM FULTON1 I. INTRODUCTION: MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH PRAGMATICALLY Many debates about whether and how to manage urban growth on a metropolitan or regional level focus on the extremes of laissez-faire capitalism and command-and-control government regulation. This paper proposes an alternative, or "third way," of managing metropolitan growth, one that seeks to steer in between the two extremes, focusing on a pragmatic approach that acknowledges both the market and government policy. Laissez-faire advocates argue that we should leave growth to the markets. If the core cities fail, it is because people don’t want to live, shop, or work there anymore. If the first ring suburbs decline, it is because their day has passed. If exurban areas begin to choke on large-lot, septic- driven subdivisions, it is because that is the lifestyle that people individually prefer. Government policy should be used to accommodate these preferences rather than seek to shape any particular regional growth pattern. Advocates on the other side call for a strong regulatory approach. Their view is that regional and state governments should use their power to engineer precisely where and how local communities should grow for the common good. Among other things, this approach calls for the creation of a strong—even heavy-handed—regional boundary that restricts urban growth to particular geographical areas. -

GAO-04-758 Metropolitan Statistical Areas

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Subcommittee on GAO Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Selected Federal Programs a GAO-04-758 June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Highlights of GAO-04-758, a report to the Selected Federal Programs Subcommittee on Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives For the past 50 years, the federal The new standards for federal statistical recognition of metropolitan areas government has had a metropolitan issued by OMB in 2000 differ from the 1990 standards in many ways. One of the area program designed to provide a most notable differences is the introduction of a new designation for less nationally consistent set of populated areas—micropolitan statistical areas. These are areas comprised of a standards for collecting, tabulating, central county or counties with at least one urban cluster of at least 10,000 but and publishing federal statistics for geographic areas in the United fewer than 50,000 people, plus adjacent outlying counties if commuting criteria States and Puerto Rico. Before is met. each decennial census, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) The 2000 standards and the latest population update have resulted in five reviews the standards to ensure counties being dropped from metropolitan statistical areas, while another their continued usefulness and 41counties that had been a part of a metropolitan statistical area have had their relevance and, if warranted, revises statistical status changed and are now components of micropolitan statistical them. -

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

Urbanistica N. 146 April-June 2011

Urbanistica n. 146 April-June 2011 Distribution by www.planum.net Index and english translation of the articles Paolo Avarello The plan is dead, long live the plan edited by Gianfranco Gorelli Urban regeneration: fundamental strategy of the new structural Plan of Prato Paolo Maria Vannucchi The ‘factory town’: a problematic reality Michela Brachi, Pamela Bracciotti, Massimo Fabbri The project (pre)view Riccardo Pecorario The path from structure Plan to urban design edited by Carla Ferrari A structural plan for a ‘City of the wine’: the Ps of the Municipality of Bomporto Projects and implementation Raffaella Radoccia Co-planning Pto in the Val Pescara Mariangela Virno Temporal policies in the Abruzzo Region Stefano Stabilini, Roberto Zedda Chronographic analysis of the Urban systems. The case of Pescara edited by Simone Ombuen The geographical digital information in the planning ‘knowledge frameworks’ Simone Ombuen The european implementation of the Inspire directive and the Plan4all project Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen, Interoperability and spatial planners: a proposal for a land use Franco Vico ‘data model’ Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen What is a land use data model? Giuseppe De Marco Interoperability and metadata catalogues Stefano Magaudda Relationships among regional planning laws, ‘knowledge fra- meworks’ and Territorial information systems in Italy Gaia Caramellino Towards a national Plan. Shaping cuban planning during the fifties Profiles and practices Rosario Pavia Waterfrontstory Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Monica Bocci Brasilia, the city of the future is 50 years old. The urban design and the challenges of the Brazilian national capital Michele Talia To research of one impossible balance Antonella Radicchi On the sonic image of the city Marco Barbieri Urban grapes. -

JUL 2 0 2006 C 2005 Sunil Tankha

The Risk of Reform: Privatisation and Liberalisation in the Brazilian Electric Power Industry by Sunil Tankha Master in Public Affairs The University of Texas at Austin, 1997 Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT at the MA SSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF TE February 2006 JUL 2 0 2006 C 2005 Sunil Tankha. All rights reserved. LIBRA RIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this these document in whole or in part. Signature of A uthor ................................................ Department of Urban Studies and Planning August 22, 2005 C ertified by ......................................... / Ali'e AmNden Professor of Political Economy Dissertation Chair Accepted by ................ Frank Levy Chair, Ph.D. Program The Risk of Reform: Privatisation and Liberalisation in the Brazilian Electric Power Industry by Sunil Tankha Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Economy ABSTRACT In 1996, when Brazil was well-underway to privatising and liberalising its electric power industry, few would have predicted that within five years the reforms would be a shambles. Like its nighbours Argentina and Chile, Brazil based its electricity reforms on the orthodox therapies of privatisation and liberalisation. The industry was well-positioned to benefit from the reforms: it was technically sophisticated, relatively efficient, and attractive to both domestic and foreign investors. Electricity rates had been suppressed for a long time, but they were not populist and it was the residential customer who cross-subsidised industry. -

An Economist's Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1, Defining Excessive

An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 Defining Excessive Decentralization in California and Other Western States California Senate Office of Research January 2002 (Revised) An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part I Defining Excessive Decentralization in California and Other Western States Prepared by Robert W. Wassmer Professor Graduate Program in Public Policy and Administration California State University Visiting Consultant California Senate Office of Research Support for this work came from the California Institute for County Government, Capital Regional Institute and Valley Vision, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, and the California State University Faculty Research Fellows in association with the California Senate Office of Research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author. Senate Office of Research Elisabeth Kersten, Director Edited by Rebecca LaVally and formatted by Lynne Stewart January 2002 (Revised) 2 An Economist’s Perspective on Urban Sprawl, Part 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary..................................................................................... 4 What is Sprawl? ........................................................................................... 5 Findings ........................................................................................................ 5 Conclusions.................................................................................................. -

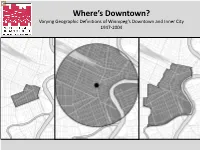

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

Introduction to Public Choice Theory Public Choice Theory Politicians As Economic Agents Median Voter Theorem PPE 101 Voters As Economic Agents

Contents: Review Theories of Economic Justice Introduction to Public Choice Theory Public Choice Theory Politicians as Economic Agents Median Voter Theorem PPE 101 Voters as Economic Agents Utilitarianism: Utilitarianism: One that maximizes overall “utility” Maximize overall “utility” (wellbeing, Theories of (wellbeing, happiness, pleasure, etc.) Theories of happiness, pleasure, etc.) Economic Rawls: Economic Rawls: One that protects basic liberties and Protect basic liberties and allow Justice allows inequalities only insofar as Justice inequalities only insofar as they they benefit the least advantaged. What is a Just Distribution? What Should the Government benefit the least advantaged. Nozick: do? Nozick: One that results from wholly Should protect individual rights, voluntary transactions and just enforce contracts, provide protection. initial acquisitions. Introduction to Introduction to Public Choice Public Choice Theory Theory Public Choice Theory: What is it? What Moves Public Choice Theory: The application of economic Politics? methods to the study of political processes. What Moves Politics? Anthony Downs American Economist Public Choice Theory: Politicians - Every agent in the division of labor has a private motive (self-interest) and a social function (the role they play within their institution). - Politics is not exempt. - Politicians pursue private motives and, in the process (if the political institutions are designed appropriately), serve a social function that benefits others. Under perfect information, Under conditions of imperfect - Voters elect those who will information, benefit them. Public Choice Public Choice - Politicians do not know what - Government expects voters to voters want. vote based on how policies affect Theory Theory - Voters don’t know what them. politicians are doing, will do, or The Argument, Part I - The opposition offers The Argument, Part II should be doing. -

Involving the Community in Inner City Renewal: a Case Study of Nanluogu in Beijing

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan Article Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing Journal of Urban Management Provided in Cooperation with: Chinese Association of Urban Management (CAUM), Taipei Suggested Citation: Zhang, Chun; Lu, Bin; Song, Yan (2012) : Involving the community in inner city renewal: A case study of Nanluogu in Beijing, Journal of Urban Management, ISSN 2226-5856, Elsevier, Amsterdam, Vol. 1, Iss. 2, pp. 53-71, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2226-5856(18)30060-8 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/194394 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.