Involving the Community in Inner City Renewal: a Case Study of Nanluogu in Beijing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

Cc6fe371d11541538bd242467c

On February 24, 2018, Henan: Home of Chinese Culture—2018 Hong Kong Happy Spring New Year Temple Fair was grandly opened in Kowloon Park in Hong Kong. On February 18, 2018, Home of Panda: Beautiful Sichuan—The Eighth Cross-Straits Spring Festival Folk Temple Fair was grandly opened at the Nantou County Convention and Exhibition Center in Taiwan. On February 2, 2018, Universal Celebrations—the People of China and the Philippines jointly welcome the New Year was held at the Commercial Center in Clarke, the Philippines. On February 22, 2018, the celebration of 2018 EU-China Tourism Year—Chinese Lanterns Light up the heart of Europe was successfully held in the Grand Place in Brussels, Belgium. Contents Express News FOCUS 04 President Li Xiaolin meets with Cambodian group /Wang Bo 04 Vice-President Xie Yuan meets granddaughter of General Chennault /Jin Hanghang 05 Vice-President Hu Sishe attends premiere of documentary film, TCM promotion tour /Yu Xiaodong 05 20th anniversary of China-South Africa diplomatic ties /Zhang Yujun 06 China-Japan friendship concert held in Beijing /Liu Mengyan 04 06 President Li Xiaolin and Secretary-General Li Xikui attend signing ceremony /Jia Ji 07 International sister city exchanges exhibition /Chengdu Friendship Association 07 The Belt and Road: 2018 Walk into Nepal photography competition / Chengdu Friendship Association 21 View 08 Kimiyo Matsuzaki, witness of ping-pong diplomacy between China and Japan /He Yan 12 The legendary life of He Lianxiang, goodwill messenger of Peru-China 36 friendship /Tang Mingxin -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 © Copyright by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The How and Why of Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China by Jonathan Stanhope Bell Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Chair China’s urban landscape has changed rapidly since political and economic reforms were first adopted at the end of the 1970s. Redevelopment of historic city centers that characterized this change has been rampant and resulted in the loss of significant historic resources. Despite these losses, substantial historic neighborhoods survive and even thrive with some degree of integrity. This dissertation identifies the multiple social, political, and economic factors that contribute to the protection and preservation of these neighborhoods by examining neighborhoods in the cities of Beijing and Pingyao as case studies. One focus of the study is capturing the perspective of residential communities on the value of their neighborhoods and their capacity and willingness to become involved in preservation decision-making. The findings indicate the presence of a complex interplay of public and private interests overlaid by changing policy and economic limitations that are creating new opportunities for public involvement. Although the Pingyao case study represents a largely intact historic city that is also a World Heritage Site, the local ii focus on tourism has disenfranchised residents in order to focus on the perceived needs of tourists. -

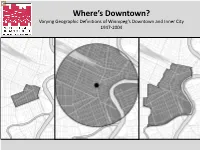

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7]. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance

Post-Cold War Experimental Theatre of China: Staging Globalisation and Its Resistance Zheyu Wei A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Creative Arts The University of Dublin, Trinity College 2017 Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library Conditions of use and acknowledgement. ___________________ Zheyu Wei ii Summary This thesis is a study of Chinese experimental theatre from the year 1990 to the year 2014, to examine the involvement of Chinese theatre in the process of globalisation – the increasingly intensified relationship between places that are far away from one another but that are connected by the movement of flows on a global scale and the consciousness of the world as a whole. The central argument of this thesis is that Chinese post-Cold War experimental theatre has been greatly influenced by the trend of globalisation. This dissertation discusses the work of a number of representative figures in the “Little Theatre Movement” in mainland China since the 1980s, e.g. Lin Zhaohua, Meng Jinghui, Zhang Xian, etc., whose theatrical experiments have had a strong impact on the development of contemporary Chinese theatre, and inspired a younger generation of theatre practitioners. Through both close reading of literary and visual texts, and the inspection of secondary texts such as interviews and commentaries, an overview of performances mirroring the age-old Chinese culture’s struggle under the unprecedented modernising and globalising pressure in the post-Cold War period will be provided. -

West End Theatre in China Transcript

West End Theatre in China Transcript Date: Monday, 15 October 2012 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 15 October 2012 The Theatre as a Key London Industry David Lightbody At 7.15pm on Monday July 11th 2011 at the Shanghai Grand Theatre in China the curtain rose on a unique and groundbreaking theatre production. The first words sung were “You yi ge meng”, “I have a dream”. The show was Mamma Mia! and it was the first, first class production of a major western musical in Chinese. As Executive Producer on behalf of Judy Craymer and Littlestar for the Chinese production it was, for me, the end of two and half years of production development. However, if I include into this the years I spent before Mamma Mia! as General Manager for Cameron Mackintosh Limited in China, it was in fact the culmination of seven years of intensive work to bring a Chinese language version of a major western musical to the Chinese people. The response to that first night was almost universally positive amongst audiences, the media and the Government. 15 months later, at this moment, the production is setting up in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province in the Yangtze River Delta, the latest stop on a tour that since Shanghai has taken in Beijing, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Xian, Chongqing, Taicang, Harbin, Tianjin, Nanjing and Xining. By the end of this year we will have performed in 17 cities to well over 300,000 people and wherever the show has gone it has broken records. I am, I think rightly, quite proud of this achievement and I believe it was largely worth the long road to bring the production to the Chinese stage. -

Take the Ming Dynasty Pottery Courtyard of Henan Museum As an Example

International Journal of Frontiers in Sociology ISSN 2706-6827 Vol. 3, Issue 4: 93-98, DOI: 10.25236/IJFS.2021.030420 On the Transition from Ming Dynasty Ceramic Courtyard to North China Residence——Take the Ming Dynasty Pottery Courtyard of Henan Museum as an Example Jiaran Zhanga,*, Yingrui Chib, Mengdi Shi School of Art and Design,Zhengzhou University of Light Industry, Zhengzhou , China. a email: [email protected], b email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract: The pottery building is not only a funerary object, but also reflects the architectural technology, plastic arts, and artistic aesthetics of the dynasty. The layout of the pottery courtyard and the layout of related houses are also the research value. The Ming Dynasty pottery courtyard unearthed in this article is a true portrayal of the residential courtyards in northern China. Keywords: Pottery Courtyard, Courtyard-Style Dwellings, Northern Dwellings 1. Pottery House, Pottery Courtyard This time I went to the Henan Museum, not only to appreciate the cultural relics but also to have a certain understanding and understanding of a part of the history of Henan. After the precipitation of history, everything becomes a cultural relic and has a story behind it. The house that will be mainly described in this article (Figure 1) is an ancient northern Chinese house, and this house is also a true portrayal of an ancient northern Chinese house. Figure 1 Pottery Garden (Self-portrait of Henan Museum) Ming wares are burial objects made in ancient China imitating real objects, and they entrust the living people's deep mourning, infinite grief, and blessings for their souls forever. -

Research Survey and Research on the Traditional Historical

6th International Conference on Management, Education, Information and Control (MEICI 2016) Research Survey and Research on the Traditional Historical Architecture in Dongcheng District of Beijing Menglin Xu Nanyang Institute of Technology, Nanyang, China jiumengni @163.com Keywords: Traditional historic buildings; Current situation; Countermeasure and suggestion Abstract. Dongcheng District keeps the largest number of historic buildings, the most widely distributed and best-preserved, most feature-rich region buildings in Beijing. The existing historic buildings in Dongcheng District are an important carrier of historical and cultural in the capital, which is also the top priority of the historical and cultural protection in Beijing today. Among these existing historic buildings, there are a large number of them haven’t been included in the current system, which still have high preservation value. The department did a thoroughly research about the three cultural relics protection units and research projects census, but didn’t do a survey to the historic buildings that except the project, even didn’t think about that. Based on information collected in the first historic building survey of Dongcheng District, Beijing. Combining the analysis of historical documents in Dongcheng District, the historic district and traditional historic buildings since the Yuan, Ming, the purpose of this paper is to do an analysis and explore the traditional historic buildings conservation value and protection methods, which also provides a lot of basic information for subsequent protection research. Introduction As the world's greatest capitals, Beijing has a strict urban planning at the beginning of Yuan Dynasty. Under the design and construction of Bingzhong Liu and the others, regular chessboard layout of streets, accurate functional partition and intricate but effective water supply systems, have been the indispensable characteristics of Beijing, which also made it famous around the world and be a paragon for capital planning. -

Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect

Culture, Society, and Praxis Volume 12 Number 1 Justice is Blindfolded Article 3 May 2020 Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect Shiqi Liang University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/csp Part of the Architecture Commons, and the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Liang, Shiqi (2020) "Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect," Culture, Society, and Praxis: Vol. 12 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/csp/vol12/iss1/3 This Main Theme / Tema Central is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culture, Society, and Praxis by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liang: Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geograph Culture, Society, and Praxis Architecture and Geography of China Proper: Influence of Geography on the Diversity of Chinese Traditional Architectural Motifs and the Cultural Values They Reflect Shiqi Liang Introduction served as the heart of early Chinese In 2016 the city government of Meixian civilization because of its favorable decided to remodel the area where my geographical and climatic conditions that family’s ancestral shrine is located into a supported early development of states and park. To collect my share of the governments. Zhongyuan is very flat with compensation money, I traveled down to few mountains; its soil is rich because of the southern China and visited the ancestral slit carried down by the Yellow River. -

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES in CHINA by Hui Meng Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the Un

SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA By Copyright 2012 Hui Meng Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa ________________________________ Misty Schieberle ________________________________ Jonathan Lamb Date Defended: April 3, 2012 ii The Thesis Committee for Hui Meng certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: SHAKESPEARE STUDIES IN CHINA ________________________________ Chairperson Geraldo U. de Sousa Date approved: April 3, 2012 iii Abstract: Different from Germany, Japan and India, China has its own unique relation with Shakespeare. Since Shakespeare’s works were first introduced into China in 1904, Shakespeare in China has witnessed several phases of developments. In each phase, the characteristic of Shakespeare studies in China is closely associated with the political and cultural situation of the time. This thesis chronicles and analyzes noteworthy scholarship of Shakespeare studies in China, especially since the 1990s, in terms of translation, literary criticism, and performances, and forecasts new territory for future studies of Shakespeare in China. iv Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………1 Section 1 Oriental and Localized Shakespeare: Translation of Shakespeare’s Plays in China …………………………………………………………………... 3 Section 2 Interpretation and Decoding: Contemporary Chinese Shakespeare Criticism……………………………………………………………….