Is Urban Decay Bad? Is Urban Revitalization Bad Too?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No

TULSA METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING COMMISSION Minutes of Meeting No. 2646 Wednesday, March 20, 2013, 1:30 p.m. City Council Chamber One Technology Center – 175 E. 2nd Street, 2nd Floor Members Present Members Absent Staff Present Others Present Covey Stirling Bates Tohlen, COT Carnes Walker Fernandez VanValkenburgh, Legal Dix Huntsinger Warrick, COT Edwards Miller Leighty White Liotta Wilkerson Midget Perkins Shivel The notice and agenda of said meeting were posted in the Reception Area of the INCOG offices on Monday, March 18, 2013 at 2:10 p.m., posted in the Office of the City Clerk, as well as in the Office of the County Clerk. After declaring a quorum present, 1st Vice Chair Perkins called the meeting to order at 1:30 p.m. REPORTS: Director’s Report: Ms. Miller reported on the TMAPC Receipts for the month of February 2013. Ms. Miller submitted and explained the timeline for the general work program for 6th Street Infill Plan Amendments and Form-Based Code Revisions. Ms. Miller reported that the TMAPC website has been improved and should be online by next week. Mr. Miller further reported that there will be a work session on April 3, 2013 for the Eugene Field Small Area Plan immediately following the regular TMAPC meeting. * * * * * * * * * * * * 03:20:13:2646(1) CONSENT AGENDA All matters under "Consent" are considered by the Planning Commission to be routine and will be enacted by one motion. Any Planning Commission member may, however, remove an item by request. 1. LS-20582 (Lot-Split) (CD 3) – Location: Northwest corner of East Apache Street and North Florence Avenue (Continued from 3/6/2013) 1. -

Managing Metropolitan Growth: Reflections on the Twin Cities Experience

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE Ted Mondale and William Fulton A Case Study Prepared for: The Brookings Institution Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy © September 2003 _____________________________________________________________________________________________ MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH: REFLECTIONS ON THE TWIN CITIES EXPERIENCE BY TED MONDALE AND WILLIAM FULTON1 I. INTRODUCTION: MANAGING METROPOLITAN GROWTH PRAGMATICALLY Many debates about whether and how to manage urban growth on a metropolitan or regional level focus on the extremes of laissez-faire capitalism and command-and-control government regulation. This paper proposes an alternative, or "third way," of managing metropolitan growth, one that seeks to steer in between the two extremes, focusing on a pragmatic approach that acknowledges both the market and government policy. Laissez-faire advocates argue that we should leave growth to the markets. If the core cities fail, it is because people don’t want to live, shop, or work there anymore. If the first ring suburbs decline, it is because their day has passed. If exurban areas begin to choke on large-lot, septic- driven subdivisions, it is because that is the lifestyle that people individually prefer. Government policy should be used to accommodate these preferences rather than seek to shape any particular regional growth pattern. Advocates on the other side call for a strong regulatory approach. Their view is that regional and state governments should use their power to engineer precisely where and how local communities should grow for the common good. Among other things, this approach calls for the creation of a strong—even heavy-handed—regional boundary that restricts urban growth to particular geographical areas. -

GAO-04-758 Metropolitan Statistical Areas

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Subcommittee on GAO Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Selected Federal Programs a GAO-04-758 June 2004 METROPOLITAN STATISTICAL AREAS New Standards and Their Impact on Highlights of GAO-04-758, a report to the Selected Federal Programs Subcommittee on Technology, Information Policy, Intergovernmental Relations and the Census, Committee on Government Reform, House of Representatives For the past 50 years, the federal The new standards for federal statistical recognition of metropolitan areas government has had a metropolitan issued by OMB in 2000 differ from the 1990 standards in many ways. One of the area program designed to provide a most notable differences is the introduction of a new designation for less nationally consistent set of populated areas—micropolitan statistical areas. These are areas comprised of a standards for collecting, tabulating, central county or counties with at least one urban cluster of at least 10,000 but and publishing federal statistics for geographic areas in the United fewer than 50,000 people, plus adjacent outlying counties if commuting criteria States and Puerto Rico. Before is met. each decennial census, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) The 2000 standards and the latest population update have resulted in five reviews the standards to ensure counties being dropped from metropolitan statistical areas, while another their continued usefulness and 41counties that had been a part of a metropolitan statistical area have had their relevance and, if warranted, revises statistical status changed and are now components of micropolitan statistical them. -

Do People Shape Cities, Or Do Cities Shape People? the Co-Evolution of Physical, Social, and Economic Change in Five Major U.S

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DO PEOPLE SHAPE CITIES, OR DO CITIES SHAPE PEOPLE? THE CO-EVOLUTION OF PHYSICAL, SOCIAL, AND ECONOMIC CHANGE IN FIVE MAJOR U.S. CITIES Nikhil Naik Scott Duke Kominers Ramesh Raskar Edward L. Glaeser César A. Hidalgo Working Paper 21620 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21620 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2015 We would like to acknowledge helpful comments from Gary Becker, Jörn Boehnke, Steven Durlauf, James Evans, Jay Garlapati, Lars Hansen, James Heckman, John Eric Humphries, Jackie Hwang, Priya Ramaswamy, Robert Sampson, Zak Stone, Erik Strand, and Nina Tobio. Mia Petkova contributed Figure 2. N.N. acknowledges the support from The MIT Media Lab consortia; S.D.K. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (grants CCF-1216095 and SES-1459912), the Harvard Milton Fund, the Wu Fund for Big Data Analysis, and the Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group (HCEO) sponsored by the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET); E.L.G. acknowledges support from the Taubman Center for State and Local Government; and C.A.H. acknowledges support from Google’s Living Lab awards and The MIT Media Lab consortia. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21620.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. -

PERSPECTIVES on the INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival

PERSPECTIVES ON THE INNER CITY: Its Changing Character, Reasons for Decline and Revival L.S. Bourne Research Paper No. 94 Draft of a chapter for "The Geography of Modern Metropolitan Systems" Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, Columbia, Ohio Centre for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto February 1978 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Objectives 3 2. WHAT AND WHERE IS THE INNER CITY? DEFINITIONS 5 AND CONCEPTS A Process Approach 6 A Problem Approach 9 3. DIVERSITY: THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE INNER CITY 14 Types of Inner City Neighborhoods 16 Social Disparities and the Inner City 20 Case Studies 25 4. WHY THE DECLINE OF THE INNER CITY? 30 The "Natural" Evolution Hypothesis 30 Preferences and Income: The "Pull" Hypothesis 32 The Obsolescence Hypothesis 35 The "Unintended" Policy Hypothesis 36 The Exploitation Hypothesis: Power, 40 Capitalism and the Political Economcy of Urbanization The Structural Change Hypothesis 43 The Fiscal Crisis and the Underclass Hypothesis 46 The Black Inner City in Cultural Isolation: 48 The Conflict Hypothesis Summary: Which Hypothesis of Decline is Correct? 51 5. BACK TO THE CITY: IS THE INNER CITY REVIVING? 55 6. CONCLUSIONS AND A LOOK AHEAD 63 Problems, Policies and Emerging Issues 66 Summary Comments 69 FOOTNOTES 71 REFERENCES 73 Preface The inner city is again a subject of widespread debate in most western countries. This paper undertakes to outline the nature of that debate and to document the reasons for inner city decline and revitalization. The argument is made that there is no single definition of the inner city which is universally ap plicable. -

Urbanistica N. 146 April-June 2011

Urbanistica n. 146 April-June 2011 Distribution by www.planum.net Index and english translation of the articles Paolo Avarello The plan is dead, long live the plan edited by Gianfranco Gorelli Urban regeneration: fundamental strategy of the new structural Plan of Prato Paolo Maria Vannucchi The ‘factory town’: a problematic reality Michela Brachi, Pamela Bracciotti, Massimo Fabbri The project (pre)view Riccardo Pecorario The path from structure Plan to urban design edited by Carla Ferrari A structural plan for a ‘City of the wine’: the Ps of the Municipality of Bomporto Projects and implementation Raffaella Radoccia Co-planning Pto in the Val Pescara Mariangela Virno Temporal policies in the Abruzzo Region Stefano Stabilini, Roberto Zedda Chronographic analysis of the Urban systems. The case of Pescara edited by Simone Ombuen The geographical digital information in the planning ‘knowledge frameworks’ Simone Ombuen The european implementation of the Inspire directive and the Plan4all project Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen, Interoperability and spatial planners: a proposal for a land use Franco Vico ‘data model’ Flavio Camerata, Simone Ombuen What is a land use data model? Giuseppe De Marco Interoperability and metadata catalogues Stefano Magaudda Relationships among regional planning laws, ‘knowledge fra- meworks’ and Territorial information systems in Italy Gaia Caramellino Towards a national Plan. Shaping cuban planning during the fifties Profiles and practices Rosario Pavia Waterfrontstory Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Monica Bocci Brasilia, the city of the future is 50 years old. The urban design and the challenges of the Brazilian national capital Michele Talia To research of one impossible balance Antonella Radicchi On the sonic image of the city Marco Barbieri Urban grapes. -

Read the Article in PDF Format

G. Skoll & M. Korstanje – The Role of Art in two Neighborhoods Cultural Anthropology 81-103 The Role of Art in Two Neighborhoods and Responses to Urban Decay and Gentrification Geoffrey R. Skoll1 and Maximiliano Korstanje2 Abstract One of the most troubling aspects of cultural studies, is the lack of comparative cases to expand the horizons of micro-sociology. Based on this, the present paper explores the effects of gentrification in two neighborhoods, Riverwest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin USA and Abasto in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Each neighborhood had diverse dynamics and experienced substantial changes in the urban design. In the former arts played a pivotal role in configuring an instrument of resistance, in the latter one, arts accompanied the expansion of capital pressing some ethnic minorities to abandon their homes. What is important to discuss seems to be the conditions where in one or another case arts take one or another path. While Riverwest has never been commoditized as a tourist-product, Abasto was indeed recycled, packaged and consumed to an international demand strongly interested in Tango music and Carlos Gardel biography. There, tourism served as an instrument of indoctrination that made serious asymmetries among Abasto neighbors, engendering social divisions and tensions which were conducive to real estate speculation and great financial investors. The concept of patrimony and heritage are placed under the lens of scrutiny in this investigation. Key Words: Abasto, Riverwest, Gentrification, Patrimonialization, Discrimination, Tourism. Riverwest: How Artistic Work Makes the Moral Bonds of a Community Social studies of art offer illuminating perspectives on art’s roles in societies, how social conditions affect art, and how the arts affect and reflect social conditions. -

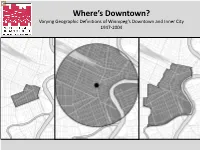

Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg's Downtown

Where’s Downtown? Varying Geographic Definitions of Winnipeg’s Downtown and Inner City 1947-2004 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Proposed Business District Zoning Boundary, 1947 Downtown, Metropolitan Winnipeg Development Plan, 1966 Pre-Amalgamation Downtown Boundary, early 1970s City Centre, 1978 Winnipeg Area Characterization Downtown Boundary, 1981 City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 Health and Social Research: Community Centre Areas Downtown Statistics Canada: Central Business District 6020025 6020024 6020023 6020013 6020014 1 mile, 2 miles, 5 km from City Hall 5 Kilometres 2 Miles 1 Mile Health and Social Research: Neighbourhood Clusters Downtown Boundary Downtown West Downtown East Health and Social Research: Community Characterization Areas Downtown Boundary Winnipeg Police Service District 1: Downtown Winnipeg School Division: Inner-city District, pre-2015 Core Area Initiative: Inner-city Boundary, 1981-1991 Neighbourhood Characterization Areas: Inner-city Boundary City of Winnipeg: Official Downtown Zoning Boundary, 2004 For more information please refer to: Badger, E. (2013, October 7). The Problem With Defining ‘Downtown’. City Lab. http://www.citylab.com/work/2013/10/problem-defining-downtown/7144/ Bell, D.J., Bennett, P.G.L., Bell, W.C., Tham, P.V.H. (1981). Winnipeg Characterization Atlas. Winnipeg, MB: The City of Winnipeg Department of Environmental Planning. City of Winnipeg. (2014). Description of Geographies Used to Produce Census Profiles. http://winnipeg.ca/census/includes/Geographies.stm City of Winnipeg. (2016). Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 100/2004. http://clkapps.winnipeg.ca/dmis/docext/viewdoc.asp?documenttypeid=1&docid=1770 City of Winnipeg. (2016). Open Data. https://data.winnipeg.ca/ Heisz, A., LaRochelle-Côté, S. -

From Urban Entrepreneurialism to a “Revanchist City”? on the Spatial Injustices of Glasgow’S Renaissance

From Urban Entrepreneurialism to a “Revanchist City”? On the Spatial Injustices of Glasgow’s Renaissance Gordon MacLeod Department of Geography, University of Durham, Durham, UK; [email protected] Recent perspectives on the American city have highlighted the extent to which the economic and sociospatial contradictions generated by two decades of “actually exist- ing” neoliberal urbanism appear to demand an increasingly punitive or “revanchist” political response. At the same time, it is increasingly being acknowledged that, after embracing much of the entrepreneurial ethos, European cities are also confronting sharpening inequalities and entrenched social exclusion. Drawing on evidence from Glasgow, the paper assesses the dialectical relations between urban entrepreneurial- ism, its escalating contradictions, and the growing compulsion to meet these with a selective appropriation of the revanchist political repertoire. Introduction Spurred on by the unrelenting pace of globalization and the entrenched political hegemony of a neoliberal ideology, throughout the last two decades a host of urban governments in North America and Western Europe have sought to recapitalize the economic land- scapes of their cities. While these “entrepreneurial” strategies might have refueled the profitability of many city spaces across the two con- tinents, the price of such speculative endeavor has been a sharpening of socioeconomic inequalities alongside the institutional displacement and “social exclusion” of certain marginalized groups. One political response to these social geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism” (Brenner and Theodore [paper] this volume) sees the continuous renaissance of the entrepreneurial city being tightly “disciplined” through a range of architectural forms and institutional practices so that the enhancement of a city’s image is not compromised by the visible presence of those very marginalized groups. -

I the MULTICULTURAL MEGALOPOLIS

i THE MULTICULTURAL MEGALOPOLIS: AFRICAN-AMERICAN SUBJECTIVITY AND IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY HARLEM FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Shamika Ann Mitchell May 2012 Examining Committee Members: Joyce A. Joyce, Ph.D., Advisory Chair, Department of English Sheldon R. Brivic, Ph.D., Department of English Roland L. Williams, Ph.D., Department of English Maureen Honey, Ph.D., Department of English, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ii © Copyright 2012 by Shamika Ann Mitchell iii ABSTRACT The central aim of this study is to explore what I term urban ethnic subjectivity, that is, the subjectivity of ethnic urbanites. Of all the ethnic groups in the United States, the majority of African Americans had their origins in the rural countryside, but they later migrated to cities. Although urban living had its advantages, it was soon realized that it did not resolve the matters of institutional racism, discrimination and poverty. As a result, the subjectivity of urban African Americans is uniquely influenced by their cosmopolitan identities. New York City‘s ethnic community of Harlem continues to function as the geographic center of African-American urban culture. This study examines how six post-World War II novels ― Sapphire‘s PUSH, Julian Mayfield‘s The Hit, Brian Keith Jackson‘s The Queen of Harlem, Charles Wright‘s The Wig, Toni Morrison‘s Jazz and Louise Meriwether‘s Daddy Was a Number Runner ― address the issues of race, identity, individuality and community within Harlem and the megalopolis of New York City. Further, this study investigates concepts of urbanism, blackness, ethnicity and subjectivity as they relate to the characters‘ identities and self- perceptions. -

Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus Between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability

sustainability Article Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability OndˇrejSlach, VojtˇechBosák, LudˇekKrtiˇcka* , Alexandr Nováˇcekand Petr Rumpel Department of Human Geography and Regional Development, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, 709 00 Ostrava, Czechia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-731-505-314 Received: 30 June 2019; Accepted: 29 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: Urban shrinkage has become a common pathway (not only) in post-socialist cities, which represents new challenges for traditionally growth-oriented spatial planning. Though in the post-socialist area, the situation is even worse due to prevailing weak planning culture and resulting uncoordinated development. The case of the city of Ostrava illustrates how the problem of (in)efficient infrastructure operation, and maintenance, in already fragmented urban structure is exacerbated by the growing size of urban area (through low-intensity land-use) in combination with declining size of population (due to high rate of outmigration). Shrinkage, however, is, on the intra-urban level, spatially differentiated. Population, paradoxically, most intensively declines in the least financially demanding land-uses and grows in the most expensive land-uses for public administration. As population and urban structure development prove to have strong inertia, this land-use development constitutes a great challenge for a city’s future sustainability. The main objective of the paper is to explore the nexus between change in population density patterns in relation to urban shrinkage, and sustainability of public finance. Keywords: Shrinking city; Ostrava; sustainability; population density; built-up area; housing 1. Introduction The study of the urban shrinkage process has ranked among established research areas in a number of scientific disciplines [1–7].