Architectural Propaganda at the World's Fairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman Architecture Roman of Classics at Dartmouth College, Where He Roman Architecture

BLACKWELL BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD COMPANIONS TO THE ANCIENT WORLD A COMPANION TO the editors A COMPANION TO A COMPANION TO Roger B. Ulrich is Ralph Butterfield Professor roman Architecture of Classics at Dartmouth College, where he roman architecture EDITED BY Ulrich and quenemoen roman teaches Roman Archaeology and Latin and directs Dartmouth’s Rome Foreign Study roman Contributors to this volume: architecture Program in Italy. He is the author of The Roman Orator and the Sacred Stage: The Roman Templum E D I T E D B Y Roger B. Ulrich and Rostratum(1994) and Roman Woodworking James C. Anderson, jr., William Aylward, Jeffrey A. Becker, Caroline k. Quenemoen (2007). John R. Clarke, Penelope J.E. Davies, Hazel Dodge, James F.D. Frakes, Architecture Genevieve S. Gessert, Lynne C. Lancaster, Ray Laurence, A COMPANION TO Caroline K. Quenemoen is Professor in the Emanuel Mayer, Kathryn J. McDonnell, Inge Nielsen, Roman architecture is arguably the most Practice and Director of Fellowships and Caroline K. Quenemoen, Louise Revell, Ingrid D. Rowland, EDItED BY Roger b. Ulrich and enduring physical legacy of the classical world. Undergraduate Research at Rice University. John R. Senseney, Melanie Grunow Sobocinski, John W. Stamper, caroline k. quenemoen A Companion to Roman Architecture presents a She is the author of The House of Augustus and Tesse D. Stek, Rabun Taylor, Edmund V. Thomas, Roger B. Ulrich, selective overview of the critical issues and approaches that have transformed scholarly the Foundation of Empire (forthcoming) as well as Fikret K. Yegül, Mantha Zarmakoupi articles on the same subject. -

Between Modernization and Preservation: the Changing Identity of the Vernacular in Italian Colonial Libya

Between Modernization and Preservation: The Changing Identity of the Vernacular in Italian Colonial Libya BRIAN MCLAREN Harvard University This paper concerns the changing identity of the vernacular The architecture of this tourist system balanced a need to project architecture of the Italian colony of Libya in architectural discourse, an image of a modern and efficient network of travel, with the desire and the related appropriation of this re-configured vernacular by to preserve and even accentuate the characteristic qualities of the architects working in thls region. In this effort, I will describe the indigenous culture of each region. In the first instance, the tourist system difference between an abstract assimilation of these influences in the in Libya offered an experience of the colonial context that was early 1930s and a more scientific interest in the indlgenous culture of fundamentally modern-facilities like the dining room at the Albergo Libya in the latter part of this decade. In the first case, the work of "alle Gazzelle" in Zliten conveying an image of metropolitan comfort. architects like Sebastiano Larco and Carlo Enrico Rava subsumed In the second, a conscious effort was made to organize indigenous cultural references to vernacular constructions into modern aesthetic practices. manifestations that would enhance the tourist experience. One In the second, archtects llke Florestano Di Fausto evinced the material prominent example were the musical and dance performances in the qualities of these buildings in works that often directly re-enacted CaffeArabo at the Suq al-Mushr, which were made in a setting that was traditional forms. However, rather than dlscuss the transformation of intended to enact the mysteries of the East. -

Do People Shape Cities, Or Do Cities Shape People? the Co-Evolution of Physical, Social, and Economic Change in Five Major U.S

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES DO PEOPLE SHAPE CITIES, OR DO CITIES SHAPE PEOPLE? THE CO-EVOLUTION OF PHYSICAL, SOCIAL, AND ECONOMIC CHANGE IN FIVE MAJOR U.S. CITIES Nikhil Naik Scott Duke Kominers Ramesh Raskar Edward L. Glaeser César A. Hidalgo Working Paper 21620 http://www.nber.org/papers/w21620 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2015 We would like to acknowledge helpful comments from Gary Becker, Jörn Boehnke, Steven Durlauf, James Evans, Jay Garlapati, Lars Hansen, James Heckman, John Eric Humphries, Jackie Hwang, Priya Ramaswamy, Robert Sampson, Zak Stone, Erik Strand, and Nina Tobio. Mia Petkova contributed Figure 2. N.N. acknowledges the support from The MIT Media Lab consortia; S.D.K. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (grants CCF-1216095 and SES-1459912), the Harvard Milton Fund, the Wu Fund for Big Data Analysis, and the Human Capital and Economic Opportunity Working Group (HCEO) sponsored by the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET); E.L.G. acknowledges support from the Taubman Center for State and Local Government; and C.A.H. acknowledges support from Google’s Living Lab awards and The MIT Media Lab consortia. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. At least one co-author has disclosed a financial relationship of potential relevance for this research. Further information is available online at http://www.nber.org/papers/w21620.ack NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. -

The American University of Rome Religious Studies Program

Disclaimer: This is an indicative syllabus only and may be subject to changes. The final and official syllabus will be distributed by the Instructor during the first day of class. The American University of Rome Religious Studies Program Department or degree program mission statement, student learning objectives, as appropriate Course Title: Sacred Space: Religious Architecture of Rome Course Number: AHRE 106 Credits & hours: 3 credits – 3 hours Pre/Co‐Requisites: None Course description The course explores main ideas behind the sacral space on the example of sacral architecture of Rome, from the ancient times to the postmodern. The course maximizes the opportunity of onsite teaching in Rome; most of the classes are held in the real surrounding, which best illustrates particular topics of the course. Students will have the opportunity to learn about different religious traditions, various religious ideas and practices (including the ancient Roman religion, early Christianity, Roman Catholicism, Orthodoxy and Protestantism, as well as the main elements of religion and sacred spaces of ancient Judaism and Islam). Students will have the opportunity to experience a variety of sacred spaces and learn about the broader cultural and historical context in which they appeared. Short study trips outside of Rome may also take place. Recommended Readings (subject to change) (Only selected chapters must be read, according to weekly schedule) Erzen, Jale Nejdet. "Reading Mosques: MeaningSyllabus and Architecture in Islam," in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. Winter, 2011, Vol. 69, 125‐131. Kilde, Jeanne Halgren. Sacred Power, Sacred Space: An Introduction to Christian Architecture and Worship. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. -

Read the Article in PDF Format

G. Skoll & M. Korstanje – The Role of Art in two Neighborhoods Cultural Anthropology 81-103 The Role of Art in Two Neighborhoods and Responses to Urban Decay and Gentrification Geoffrey R. Skoll1 and Maximiliano Korstanje2 Abstract One of the most troubling aspects of cultural studies, is the lack of comparative cases to expand the horizons of micro-sociology. Based on this, the present paper explores the effects of gentrification in two neighborhoods, Riverwest in Milwaukee, Wisconsin USA and Abasto in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Each neighborhood had diverse dynamics and experienced substantial changes in the urban design. In the former arts played a pivotal role in configuring an instrument of resistance, in the latter one, arts accompanied the expansion of capital pressing some ethnic minorities to abandon their homes. What is important to discuss seems to be the conditions where in one or another case arts take one or another path. While Riverwest has never been commoditized as a tourist-product, Abasto was indeed recycled, packaged and consumed to an international demand strongly interested in Tango music and Carlos Gardel biography. There, tourism served as an instrument of indoctrination that made serious asymmetries among Abasto neighbors, engendering social divisions and tensions which were conducive to real estate speculation and great financial investors. The concept of patrimony and heritage are placed under the lens of scrutiny in this investigation. Key Words: Abasto, Riverwest, Gentrification, Patrimonialization, Discrimination, Tourism. Riverwest: How Artistic Work Makes the Moral Bonds of a Community Social studies of art offer illuminating perspectives on art’s roles in societies, how social conditions affect art, and how the arts affect and reflect social conditions. -

I the MULTICULTURAL MEGALOPOLIS

i THE MULTICULTURAL MEGALOPOLIS: AFRICAN-AMERICAN SUBJECTIVITY AND IDENTITY IN CONTEMPORARY HARLEM FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Shamika Ann Mitchell May 2012 Examining Committee Members: Joyce A. Joyce, Ph.D., Advisory Chair, Department of English Sheldon R. Brivic, Ph.D., Department of English Roland L. Williams, Ph.D., Department of English Maureen Honey, Ph.D., Department of English, University of Nebraska-Lincoln ii © Copyright 2012 by Shamika Ann Mitchell iii ABSTRACT The central aim of this study is to explore what I term urban ethnic subjectivity, that is, the subjectivity of ethnic urbanites. Of all the ethnic groups in the United States, the majority of African Americans had their origins in the rural countryside, but they later migrated to cities. Although urban living had its advantages, it was soon realized that it did not resolve the matters of institutional racism, discrimination and poverty. As a result, the subjectivity of urban African Americans is uniquely influenced by their cosmopolitan identities. New York City‘s ethnic community of Harlem continues to function as the geographic center of African-American urban culture. This study examines how six post-World War II novels ― Sapphire‘s PUSH, Julian Mayfield‘s The Hit, Brian Keith Jackson‘s The Queen of Harlem, Charles Wright‘s The Wig, Toni Morrison‘s Jazz and Louise Meriwether‘s Daddy Was a Number Runner ― address the issues of race, identity, individuality and community within Harlem and the megalopolis of New York City. Further, this study investigates concepts of urbanism, blackness, ethnicity and subjectivity as they relate to the characters‘ identities and self- perceptions. -

1920S Small Homes Survey Report

Discover Denver Know It. Love It. One Building at a Time. Survey Report Pilot Area #2 1920s Small Homes Park Hill, Harkness Heights, Grand View Prepared By: Jessica Aurora Ugarte and Beth Glandon Historic Denver, Inc. 1420 Ogden Street, #202 Denver, CO 80218 Rev. May 4, 2015 With Support From: 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Funding Acknowledgement ............................................................................................................................... 4 Project Areas .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Research Design & Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Historic Context ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Context, Theme and Property Type ......................................................................................................................... 18 Results ...................................................................................................................................................................... 19 Data ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2018 A Study of the Pantheon Through Time Caitlin Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Caitlin, "A Study of the Pantheon Through Time" (2018). Honors Theses. 1689. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1689 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Study of the Pantheon Through Time By Caitlin Williams * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Classics UNION COLLEGE June, 2018 ABSTRACT WILLIAMS, CAITLIN A Study of the Pantheon Through Time. Department of Classics, June, 2018. ADVISOR: Hans-Friedrich Mueller. I analyze the Pantheon, one of the most well-preserVed buildings from antiquity, through time. I start with Agrippa's Pantheon, the original Pantheon that is no longer standing, which was built in 27 or 25 BC. What did it look like originally under Augustus? Why was it built? We then shift to the Pantheon that stands today, Hadrian-Trajan's Pantheon, which was completed around AD 125-128, and represents an example of an architectural reVolution. Was it eVen a temple? We also look at the Pantheon's conversion to a church, which helps explain why it is so well preserVed. -

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: the 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike

Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike By Leigh Campbell-Hale B.A., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, 1977 M.A., University of Colorado, Boulder, 2005 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado and Committee Members: Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas G. Andrews Mark Pittenger Lee Chambers Ahmed White In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History 2013 This thesis entitled: Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike written by Leigh Campbell-Hale has been approved for the Department of History Phoebe S.K. Young Thomas Andrews Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. ii Campbell-Hale, Leigh (Ph.D, History) Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike Dissertation directed by Associate Professor Phoebe S.K. Young This dissertation examines the causes, context, and legacies of the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike in relationship to the history of labor organizing and coalmining in both Colorado and the United States. While historians have written prolifically about the Ludlow Massacre, which took place during the 1913- 1914 Colorado coal strike led by the United Mine Workers of America, there has been a curious lack of attention to the Columbine Massacre that occurred not far away within the 1927-1928 Colorado coal strike, led by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). -

Denver Public Library Clipping Files

DENVER CLIPPINGS Last printed out: 2005 Last Updates 5/21/19 CR See also: GENERAL CLIPPINGS “SEE:” References located at END of this file DENVER. See also: DENVER. METROPOLITAN AREA. DENVER. ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS SERIES. DO YOU KNOW YOUR DENVER. DENVER. 150 YEAR BIRTHDAY DENVER. Other towns / cities named “Denver,” see: DENVER. SISTER CITIES. DENVER. 1858-1859. DENVER. 1860-1869. DENVER. 1870-1879. DENVER. 1880-1889. DENVER. 1890-1899. DENVER. 1900-1909. DENVER. 1910-1919. DENVER. 1920-1929. DENVER. 1930-1939. DENVER. 1940-1949. DENVER. 1950-1959. DENVER. 1950-1959. DENVER: A PROGRESS REPORT OF THE GREATER DENVER AREA. 1957. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT TO EMPIRE MAGAZINE. DENVER. 1950-1959. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1950-1959. THE QUEEN CITY: A MILE HIGH AND STILL GROWING. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT. DENVER. 1960-1969. 1 DENVER. 1960-1969. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1960-1969. TEN STEPS TO GREATNESS. SERIES. 1964. DENVER. 1970-1979. DENVER. 1970-1979. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1970-1979. THE WHOLE CONSUMER GUIDE: A DENVER AREA GUIDE TO CONSUMER AND HUMAN RESOURCES. DENVER POST SUPPLEMENT. NOVEMBER 5, 1978. DENVER. 1980-1989. DENVER. 1980-1989. MAGAZINE EXCERPTS. DENVER. 1990-1999. DENVER. 2000-2009. DENVER. 2003. THE MILE HIGH CITY. DENVER. DENVER. 2008. 2008 OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE. DENVER. A SHORT HISTORY OF DENVER. 1 OF 2. DENVER. A SHORT HISTORY OF DENVER. 2 OF 2. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1860-1899. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1890-1899. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1900-1909. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1910-1919. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1920-1929. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1930-1939. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1940-1949. DENVER. AFRICAN AMERICANS. 1950-1959. DENVER. -

Italian Villas and Their Gardens

Italian Villas and Their Gardens By Edith Wharton INTRODUCTION ITALIAN GARDEN-MAGIC Though it is an exaggeration to say that there are no flowers in Italian gardens, yet to enjoy and appreciate the Italian garden-craft one must always bear in mind that it is independent of floriculture. The Italian garden does not exist for its flowers; its flowers exist for it: they are a late and infrequent adjunct to its beauties, a parenthetical grace counting only as one more touch in the general effect of enchantment. This is no doubt partly explained by the difficulty of cultivating any but spring flowers in so hot and dry a climate, and the result has been a wonderful development of the more permanent effects to be obtained from the three other factors in garden-composition—marble, water and perennial verdure—and the achievement, by their skilful blending, of a charm independent of the seasons. It is hard to explain to the modern garden-lover, whose whole conception of the charm of gardens is formed of successive pictures of flower-loveliness, how this effect of enchantment can be produced by anything so dull and monotonous as a mere combination of clipped green and stonework. The traveller returning from Italy, with his eyes and imagination full of the ineffable Italian garden-magic, knows vaguely that the enchantment exists; that he has been under its spell, and that it is more potent, more enduring, more intoxicating to every sense than the most elaborate and glowing effects of modern horticulture; but he may not have found the key to the mystery. -

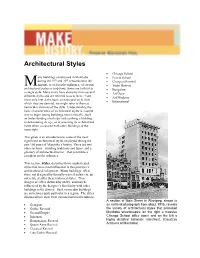

Architectural Style Guide.Pdf

Architectural Styles Chicago School any buildings constructed in Manitoba Prairie School th th during the 19 and 20 centuries bear the Georgian Revival M imprint, or at least the influence, of certain Tudor Revival architectural styles or traditions. Some are faithful to Bungalow a single style. Many more have elements from several Art Deco different styles and are referred to as eclectic. Even Art Moderne more only hint at the basic architectural style from International which they are derived; we might refer to them as vernacular versions of the style. Understanding the basic characteristics of architectural styles is a useful way to begin seeing buildings more critically. Such an understanding also helps in describing a building, in determining its age, or in assessing its architectural value when compared with other buildings of the same style. This guide is an introduction to some of the most significant architectural styles employed during the past 150 years of Manitoba’s history. There are two other sections—building traditions and types, and a glossary of architectural terms—that constitute a complete set for reference. This section, Styles, describes those sophisticated styles that were most influential in this province’s architectural development. Many buildings, often those not designed by formally-trained architects, do not relate at all to these historical styles. Their designs are often dictated by utility, and may be influenced by the designer’s familiarity with other buildings in the district. Such vernacular buildings are sometimes quite particular to a region. The styles discussed here stem from various historical traditions. A section of Main Street in Winnipeg, shown in Georgian an archival photograph from about 1915, reveals Gothic Revival the variety of architectural styles that animated Second Empire Manitoba streetscapes: on the right a massive Italianate Chicago School office tower and on the left a Romanesque Revival highly detailed Italianate storefront.