Between Modernization and Preservation: the Changing Identity of the Vernacular in Italian Colonial Libya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study on Structural Assessment and Restoration of King Zog's Villa in Durres, Albania

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epoka University 2nd International Balkans Conference on Challenges of Civil Engineering, BCCCE, 23-25 May 2013, Epoka University, Tirana, Albania. A case study on structural assessment and restoration of King Zog's villa in Durres, Albania Kujtime Barushi1, Enea Mustafaraj2 1Department of Architecture, Epoka University, Albania 2Department of Civil Engineering, Epoka University, Albania Abstract The city of Durres is the second largest city and one of the oldest ones in Albania. Its existence dates back to 627 BC. There are found many historical monuments that carry significant importance to the city. The Royal King Zog’s Villa in Durres is one of the most interesting structures built in Albania during the Albanian Monarchy period (1928-1939). The villa, located on top of the hill with the height of 98 meters above sea level, was a gift given by the merchants of the city of Durres for King Zog in 1926. The Albanian architect Kristo Sotiri designed it. During its existence, due to amortization and the lack of maintenance, the structural properties of the villa were weakened and the architectural values were dimmed. In this paper, architectural features and current structural conditions of the villa will be analyzed. The methodology used in this study is based on visual inspection of the current condition of the structure as well as a historical survey about the major changes the villa has passed through during the past years. INTRODUCTION The city of Durres is the second largest city and one of the oldest ones in Albania. -

Libyan Eclipse 2006

Libyan Eclipse 2006 HIGHLIGHTS PACK Libyan Eclipse 2006 By Anthony Ham Anthony’s love affair with Libya began on his first visit in 2001, and by the time he’d fin- ished Lonely Planet’s guide to Libya a few months later, the country had won his heart. First drawn to the country by its isolation and by his experience elsewhere of the Arab hospitality that puts to shame media stereotyping about the region, Anthony quickly made numerous Libyan friends and set about pursuing his new passion with them – exploring the inexpressible beauty of the Sahara. A full-time writer and photographer, Anthony returns to Libya from his home in Madrid whenever he can and loves the fact that the world is finally discovering that Libya is so much more than Colonel Gaddafi. ALSO AVAILABLE FROM LONELY PLANET Eclipse predictions courtesy of Fred Espenak, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. For more information on solar and lunar eclipses, see Fred Espenak’s eclipse home page: http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/eclipse.html. © Lonely Planet 2006. Published by Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd ABN 36 005 607 983 © photographers as indicated 2006. Cover photographs by Lonely Planet Images: Shadows along a ridge of sand dunes in the Awbari Sand Sea, Jane Sweeney; Halo of sunlight glowing around the silhouette of the moon during a total solar eclipse, Karl Lehmann. Many of the images in this guide are available for licensing from Lonely Planet Images: www.lonelyplanetimages.com AVAILABLE APRIL 2006 ORDER NOW All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Italian Villas and Their Gardens

Italian Villas and Their Gardens By Edith Wharton INTRODUCTION ITALIAN GARDEN-MAGIC Though it is an exaggeration to say that there are no flowers in Italian gardens, yet to enjoy and appreciate the Italian garden-craft one must always bear in mind that it is independent of floriculture. The Italian garden does not exist for its flowers; its flowers exist for it: they are a late and infrequent adjunct to its beauties, a parenthetical grace counting only as one more touch in the general effect of enchantment. This is no doubt partly explained by the difficulty of cultivating any but spring flowers in so hot and dry a climate, and the result has been a wonderful development of the more permanent effects to be obtained from the three other factors in garden-composition—marble, water and perennial verdure—and the achievement, by their skilful blending, of a charm independent of the seasons. It is hard to explain to the modern garden-lover, whose whole conception of the charm of gardens is formed of successive pictures of flower-loveliness, how this effect of enchantment can be produced by anything so dull and monotonous as a mere combination of clipped green and stonework. The traveller returning from Italy, with his eyes and imagination full of the ineffable Italian garden-magic, knows vaguely that the enchantment exists; that he has been under its spell, and that it is more potent, more enduring, more intoxicating to every sense than the most elaborate and glowing effects of modern horticulture; but he may not have found the key to the mystery. -

The Human Conveyor Belt : Trends in Human Trafficking and Smuggling in Post-Revolution Libya

The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya March 2017 A NETWORK TO COUNTER NETWORKS The Human Conveyor Belt : trends in human trafficking and smuggling in post-revolution Libya Mark Micallef March 2017 Cover image: © Robert Young Pelton © 2017 Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Please direct inquiries to: The Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime WMO Building, 2nd Floor 7bis, Avenue de la Paix CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland www.GlobalInitiative.net Acknowledgments This report was authored by Mark Micallef for the Global Initiative, edited by Tuesday Reitano and Laura Adal. Graphics and layout were prepared by Sharon Wilson at Emerge Creative. Editorial support was provided by Iris Oustinoff. Both the monitoring and the fieldwork supporting this document would not have been possible without a group of Libyan collaborators who we cannot name for their security, but to whom we would like to offer the most profound thanks. The author is also thankful for comments and feedback from MENA researcher Jalal Harchaoui. The research for this report was carried out in collaboration with Migrant Report and made possible with funding provided by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway, and benefitted from synergies with projects undertaken by the Global Initiative in partnership with the Institute for Security Studies and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, the United Nations University, and the UK Department for International Development. About the Author Mark Micallef is an investigative journalist and researcher specialised on human smuggling and trafficking. -

The Jebel Nafusa & Ghadames

© Lonely Planet Publications 157 The Jebel Nafusa & Ghadames The barren Jebel Nafusa (Western Mountains) is Libya’s Berber heartland and one of Libya’s most intriguing corners, a land of stone villages on rocky perches and otherworldly Berber architecture. The fortress-like architecture of the jebel reflects the fact that this is a land of extremes. Bitterly cold winters – snowfalls are rare but not unheard of – yield to summers less punishing than elsewhere in Libya, though the southern reaches of the Jebel Nafusa merge imperceptibly with the scorching Sahara. It was to here that many Berbers retreated from invading Arab armies in the 7th century, and the Jebel Nafusa remains one of the few areas in Libya where Berber culture still thrives. Con- sequently, the jebel’s human landscape is as fascinating as its geography and architecture. The Jebel Nafusa merits as much time as you can spare. From the underground houses of Gharyan in the east to the crumbling qasr (fortified granary store) and old town of Nalut in the west, imagination and necessity have fused into the most improbable forms. Nowhere is this more true than in Qasr al-Haj and Kabaw where the wonderful qasrs look like a back- drop to a Star Wars movie. Elsewhere, the abandoned stone village of Tarmeisa surveys the coastal plain from its precipitous rocky perch, while Yefren makes an agreeable base. Beyond the jebel on Libya’s western frontier lies one of the world’s best-preserved oasis towns. Ghadames is an enchanted spot, a labyrinthine caravan town of covered passageways, intricately decorated houses, beautiful palm gardens and a pace of life perfectly attuned to the dictates of the desert. -

Petroleum Generation and Migration in The

Petroleum generation and AUTHORS Ruth Underdown North Africa Research migration in the Ghadames Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Basin, north Africa: Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, United Kingdom; [email protected] A two-dimensional Ruth Underdown obtained her first degree in geology from the University of St. Andrews, basin-modeling study Scotland, an M.Sc. degree in petroleum geo- science from Imperial College, London, and a Ph.D. from the University of Manchester, Ruth Underdown and Jonathan Redfern United Kingdom, in 2006, funded by the North Africa Research Group. She is currently teach- ing in the United Kingdom. ABSTRACT Jonathan Redfern North Africa Research The Ghadames Basin contains important oil- and gas-producing res- Group, School of Earth, Atmospheric and En- vironmental Sciences, University of Manchester, ervoirs distributed across Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya. Regional two- Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PL, United dimensional (2-D) modeling, using data from more than 30 wells, Kingdom; [email protected] has been undertaken to assess the timing and distribution of hydro- carbon generation in the basin. Four potential petroleum systems Jonathan Redfern obtained his B.Sc. degree in geology from the University of London, Chelsea have been identified: (1) a Middle–Upper Devonian (Frasnian) and College, in 1983, and a Ph.D. from Bristol Uni- Triassic (Triassic Argilo Gre´seux Infe´rieur [TAG-I]) system in the versity, United Kingdom, in 1989. He worked central-western basin; (2) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Triassic in the oil industry for 12 years, initially with (TAG-I) system to the far west; (3) a Lower Silurian (Tannezuft) and Petrofina in the United Kingdom, southeast Asia, Upper Silurian (Acacus) system in the eastern and northeastern and Libya, and subsequently with Hess. -

Architectural Propaganda at the World's Fairs

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2016 Architectural Propaganda at the World’s Fairs Jason C. Huggins Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Recommended Citation Huggins, Jason C., "Architectural Propaganda at the World’s Fairs" (2016). All Regis University Theses. 707. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/707 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. The materials may not be downloaded in whole or in part without permission of the copyright holder or as otherwise authorized in the “fair use” standards of the U.S. -

Italian Art Nouveau Architecture

MATEC Web of Conferences 5 3, 02004 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/matecconf/201653002 04 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2016 The Liberty Style - Italian Art Nouveau Architecture Vasilii Goriunov1,a 1St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering, 2-Krasnoarmejskaja, 4, Saint-Petersburg, 190005, Russia Abstract. This article refers the architecture of Italy of the end of the 19- the beginning of the 20 centuries. It shoes the origin of the term “Italian Liberty architecture”, its main centers, its peculiarities and the buildings of its leading representatives. The assessment of importance of such studies provide the right understanding of the processes in European architecture of this time. 1 Introduction All historians of architecture know very well that the term Art Nouveau has a lot of synonyms, accepted by researches of different countries. Most of these terms do not reflect the essence of the things and they are used conditionally. The exception is the term “ Liberty Stile” although its origin also seems accidental like the origin of the majority of its synonyms. This term came from the name of the founder of British trading company which specialized on artworks from Japan and China. This was the reason for the fact that many researchers are not quite accurately called this company one of the conductors of Japanese influence on European art. This was true as long as the company was engaged in the export of the works of art only. Soon, however the company began to cooperate with young British artists of applied art who created company s own style, which brought it European s fame. -

The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Valentina Follo University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Follo, Valentina, "The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 858. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/858 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power of Images in the Age of Mussolini Abstract The year 1937 marked the bimillenary of the birth of Augustus. With characteristic pomp and vigor, Benito Mussolini undertook numerous initiatives keyed to the occasion, including the opening of the Mostra Augustea della Romanità , the restoration of the Ara Pacis , and the reconstruction of Piazza Augusto Imperatore. New excavation campaigns were inaugurated at Augustan sites throughout the peninsula, while the state issued a series of commemorative stamps and medallions focused on ancient Rome. In the same year, Mussolini inaugurated an impressive square named Forum Imperii, situated within the Foro Mussolini - known today as the Foro Italico, in celebration of the first anniversary of his Ethiopian conquest. The Forum Imperii's decorative program included large-scale black and white figural mosaics flanked by rows of marble blocks; each of these featured inscriptions boasting about key events in the regime's history. This work examines the iconography of the Forum Imperii's mosaic decorative program and situates these visual statements into a broader discourse that encompasses the panorama of images that circulated in abundance throughout Italy and its colonies. -

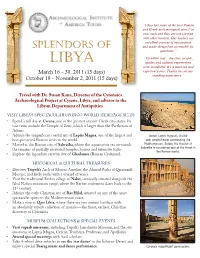

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

Florestano Di Fausto and the Politics of Mediterraneità

*Please click on ‘Supporting Material ’ link in left column to access image files * The Light and the Line: Florestano Di Fausto and the Politics of Mediterraneità Sean Anderson Architecture was born in the Mediterranean and triumphed in Rome in the eternal monuments created from the genius of our birth: it must, therefore, remain Mediterranean and Italian. 1 On March 15, 1937 along the Via Balbia, an 1800-kilometer coastal road linking Tunisia and Egypt, Benito Mussolini and Italo Balbo, then provincial governor of Italian Libya, inaugurated the Arco di Fileni, a monumental gateway commemorating two legendary Carthaginian hero- brothers, while on their way to Tripoli to celebrate the first anniversary of the Italian colonial empire. Designed by the architect Florestano Di Fausto, the travertine arch, with its elongated archway and stacked pyramidal 31-meter high profile, was built atop a purported 500 BCE site that marked the division between the Greek territory of Cyrene and Carthaginian holdings to the east. Atop the arch, an inscription by the poet Horace, made popular by the Fascist party with a stamp issued in 1936, emphasized the gateway’s prominence in visual terms: “O quickening sun, may naught be present to thy view more than the city of Rome.”2 The distant horizon of Rome, or more broadly, that of the newfound empire, framed by the arch, condensed an architectural, political, and spectral heroism that was akin to the civilizing mission of Italian colonialism. Here, the triumphant building of the arch, the road that passed through it, and the transformation of the Libyan landscape denoted the symbolic passage of an Italian consciousness into what formerly been indeterminate terrain. -

Inter Cultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome 2019

Intercultural Understanding, 2019, volume 9, pages 30-38 Inter Cultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome 2019 A general exchange agreement between Mukogawa Women’s University (MWU) and Bahçeúehir㻌 University (BAU) was signed㻌 on December 8, 2008. According to this agreement, 11 Japanese second-year master’s degree students majoring in architecture visited Italy from February 19, 2019, to March 2, 2019. The purpose of “Intercultural Studies of Architecture (ICSA) in Rome” program is to gain a deeper understanding of western architecture and art. Italy is a country well known for its extensive cultural heritage and architecture. Many of the western world’s construction techniques are based, on Italy’s heritage and architecture. Therefore, Italy was selected as the most appropriate destination for this program. Based on Italy’s historic background, the students were able to investigate the structure, construction methods, spatial composition, architectural style, artistic desires based on social conditions, and design intentions of architects and artists for various buildings. This year’s program focused on “ancient Roman architecture and sculpture,” “early Christian architecture,” “Renaissance architecture, sculpture, and garden,” and “Baroque architecture and sculpture. ” Before the ICSA trip to Rome, the students attended seminars on studying historic places during their visit abroad and were asked to make a presentation about the stuff that they learned during these seminars. During their trip to Rome, the students had the opportunity to deepen their understanding of architecture and art, measure the height and span of architecture, and draw sketches and make presentations related to some sites that they have visited. A report describing the details of this program is given below.