European Earwig Forficula Auricularia Linnaeus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chromosome-Level Genome Assembly of the Horned-Gall Aphid, Schlechtendalia

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.17.431348; this version posted February 18, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Chromosome-level genome assembly of the horned-gall aphid, Schlechtendalia 2 chinensis (Hemiptera: Aphididae: Erisomatinae) 3 4 Hong-Yuan Wei1#, Yu-Xian Ye2#, Hai-Jian Huang4, Ming-Shun Chen3, Zi-Xiang Yang1*, Xiao-Ming Chen1*, 5 Chuan-Xi Zhang2,4* 6 1Research Institute of Resource Insects, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Kunming, China 7 2Institute of Insect Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China 8 3Department of Entomology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA 9 4State Key Laboratory for Managing Biotic and Chemical Threats to the Quality and Safety of Agro-products; 10 Key Laboratory of Biotechnology in Plant Protection of MOA of China and Zhejiang Province, Institute of Plant 11 Virology, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China 12 #Contributed equally. 13 *Correspondence 14 Zi-Xiang Yang, Research Institute of Resource Insects, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Kunming, China. 15 E-mail: [email protected] 16 Xiao-Ming Chen, Research Institute of Resource Insects, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Kunming, China. 17 E-mail: [email protected] 18 Chuan-Xi Zhang, Institute of Insect Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China. 19 E-mail: [email protected] 20 Funding information 21 National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award number: 31872305, U1402263; The basic research 22 program of Yunnan Province, Grant/Award number: 202001AT070016; The grant for Innovative Team of ‘Insect 23 Molecular Ecology and Evolution’ of Yunnan Province 24 25 Abstract 26 The horned gall aphid Schlechtendalia chinensis, is an economically important insect that induces 27 galls valuable for medicinal and chemical industries. -

A Revision of the Dibrachys Cavus Species Complex (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea: Pteromalidae)

Zootaxa 2937: 1–30 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A revision of the Dibrachys cavus species complex (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea: Pteromalidae) RALPH S. PETERS1,3 & HANNES BAUR2 1Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Invertebrates, Natural History Museum, Bernastrasse 15, 3005 Bern, Switzerland. E-mail: [email protected] 3Corresponding author Abstract The taxonomy and host ranges of the cavus species complex within Dibrachys Förster (Chalcidoidea: Pteromalidae) are revised. Examination of about 810 specimens, including multivariate morphometric analysis of 21 quantitative characters clearly separated three species, Dibrachys microgastri (Bouché, 1834), Dibrachys lignicola Graham, 1969, and Dibrachys verovesparum Peters & Baur sp. n., but allowed no further subdivision of taxa according to origin, host association or previous taxonomic concepts. A neotype is designated for D. microgastri and under this name are placed in synonymy the names Dibrachys cavus (Walker, 1835) syn. n. (including eight current junior synonyms), Dibrachys clisiocampae (Fitch, 1856) syn. n. (including five current junior synonyms), Dibrachys boarmiae (Walker, 1863) syn. n., and Dibrachys ele- gans (Szelényi, 1981) syn. n. Dibrachys goettingenus Doganlar, 1987 syn. n. is synonymized under D. lignicola. The mor- phological analyses revealed several new qualitative and quantitative characters for separating taxa in this species complex and an identification key and diagnoses are provided for females and males. Dibrachys microgastri is a polypha- gous generalist pupal ectoparasitoid of several different orders of holometabolous insects, whereas D. lignicola is a polyphagous ectoparasitoid of hosts in Diptera, Lepidoptera and Hymenoptera, and D. -

Taxonomy of Iberian Anisolabididae (Dermaptera)

Acta Zoologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 63(1), pp. 29–43, 2017 DOI: 10.17109/AZH.63.1.29.2017 TAXONOMY OF IBERIAN ANISOLABIDIDAE (DERMAPTERA) Mario García-París Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, MNCN-CSIC c/José Gutiérrez Abascal, 2, 28006, Madrid. Spain. E-mail: [email protected] An update on the taxonomy and geographic distribution of Iberian Anisolabididae (Der- maptera) is provided. Former catalogues reported in the Iberian Peninsula three genera of Anisolabididae: Aborolabis, Anisolabis, and Euborellia. A revision of 487 specimens of Iberian and North African Anisolabidoidea permit to exclude the genus Aborolabis from the Iberian fauna, the re-assignation of inland Euborellia annulipes Iberian records to Euborellia moesta, and the exclusion of Aborolabis angulifera from Northwestern Africa. Examination of type materials of Aborolabis mordax and Aborolabis cerrobarjai allows to propose the treatment of A. cerrobarjai as a junior synonym of A. mordax. The diagnostic characters of Euborellia his- panica are included within the local variability found in E. moesta. I propose that E. hispanica should be treated as a junior synonym of E. moesta. Key words: earwigs, systematics, Mediterranean region, Spain, Morocco, NW Africa. INTRODUCTION The Iberian fauna of Dermaptera, including Anisolabididae Verhoeff, 1902, has been the subject of diverse revisionary (Bolívar 1876, 1897, Lapeira & Pascual 1980, Herrera Mesa 1980, Bivar de Sousa 1997) and compilatory works (Herrera Mesa 1999). These revisions together with the monograph of the Fauna of France (Albouy & Caussanel 1990) and the on-line information included in Fauna Europaea (Haas 2010), rendered the image of Dermaptera as a well known group in continental western Europe. -

STUDIES on the DERMAPTERA of the PHILIPPINES1 by G

Pacific Insects 17(1): 99-138 1 October 1976 STUDIES ON THE DERMAPTERA OF THE PHILIPPINES1 By G. K. Srivastava2 Abstract: This paper includes the description of 18 new species belonging to the genera Diplatys, Epilandex, Chaetospania, Auchenomus, Apachyus, Allostethus, Proreus, Adiathella, Kosmetor and Timomenus. Besides these, 2 species are reported for the first time from the Philippine Islands. Our knowledge of the fauna of the Philippine Islands is largely based on the works of Caudell (1904), BoreUi (1915a, b, 1916, 1917, 1918,1921,1923,1926), Brindle (1966,1967) and Ramamurthi (1967). Recently, Srivastava (in press) has studied a collection of earwigs belonging to the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, which has resulted in the description of 14 new species. The present paper contains an account of some Dermaptera recently received for study from the Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii. The collection comprises 55 species (excluding 22 represented by either females or nymphs, identified up to generic level only) belonging to 28 genera, of which 18 species are new to science and 2 others are reported for the first time from the Philippines. The genus Apachyus Serville, hitherto unknown from the Philippine Islands, is represented by a new species. For some species that are represented by a large series in the collection it has been possible to study in detail the range of variations. A few females and nymphs could not be identified because the taxonomy of the whole order is based mainly on males, which often makes identification difficult. The fauna of the Philippine Islands appears to be not only rich in the number of species but also in the multiplicity of individuals for some species. -

Phylogeny of Morphologically Modified Epizoic Earwigs Based on Molecular Evidence

When the Body Hides the Ancestry: Phylogeny of Morphologically Modified Epizoic Earwigs Based on Molecular Evidence Petr Kocarek1*, Vaclav John2, Pavel Hulva2,3 1 Department of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic, 3 Life Science Research Centre, Faculty of Science, University of Ostrava, Ostrava, Czech Republic Abstract Here, we present a study regarding the phylogenetic positions of two enigmatic earwig lineages whose unique phenotypic traits evolved in connection with ectoparasitic relationships with mammals. Extant earwigs (Dermaptera) have traditionally been divided into three suborders: the Hemimerina, Arixeniina, and Forficulina. While the Forficulina are typical, well-known, free-living earwigs, the Hemimerina and Arixeniina are unusual epizoic groups living on molossid bats (Arixeniina) or murid rodents (Hemimerina). The monophyly of both epizoic lineages is well established, but their relationship to the remainder of the Dermaptera is controversial because of their extremely modified morphology with paedomorphic features. We present phylogenetic analyses that include molecular data (18S and 28S ribosomal DNA and histone-3) for both Arixeniina and Hemimerina for the first time. This data set enabled us to apply a rigorous cladistics approach and to test competing hypotheses that were previously scattered in the literature. Our results demonstrate that Arixeniidae and Hemimeridae belong in the dermapteran suborder Neodermaptera, infraorder Epidermaptera, and superfamily Forficuloidea. The results support the sister group relationships of Arixeniidae+Chelisochidae and Hemimeridae+Forficulidae. This study demonstrates the potential for rapid and substantial macroevolutionary changes at the morphological level as related to adaptive evolution, in this case linked to the utilization of a novel trophic niche based on an epizoic life strategy. -

Biodiversity Climate Change Impacts Report Card Technical Paper 12. the Impact of Climate Change on Biological Phenology In

Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Biodiversity Climate Change impacts report card technical paper 12. The impact of climate change on biological phenology in the UK Tim Sparks1 & Humphrey Crick2 1 Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, CV1 5FB 2 Natural England, Eastbrook, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8DR Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Executive summary Phenology can be described as the study of the timing of recurring natural events. The UK has a long history of phenological recording, particularly of first and last dates, but systematic national recording schemes are able to provide information on the distributions of events. The majority of data concern spring phenology, autumn phenology is relatively under-recorded. The UK is not usually water-limited in spring and therefore the major driver of the timing of life cycles (phenology) in the UK is temperature [H]. Phenological responses to temperature vary between species [H] but climate change remains the major driver of changed phenology [M]. For some species, other factors may also be important, such as soil biota, nutrients and daylength [M]. Wherever data is collected the majority of evidence suggests that spring events have advanced [H]. Thus, data show advances in the timing of bird spring migration [H], short distance migrants responding more than long-distance migrants [H], of egg laying in birds [H], in the flowering and leafing of plants[H] (although annual species may be more responsive than perennial species [L]), in the emergence dates of various invertebrates (butterflies [H], moths [M], aphids [H], dragonflies [M], hoverflies [L], carabid beetles [M]), in the migration [M] and breeding [M] of amphibians, in the fruiting of spring fungi [M], in freshwater fish migration [L] and spawning [L], in freshwater plankton [M], in the breeding activity among ruminant mammals [L] and the questing behaviour of ticks [L]. -

The Genetic Mechanism of Selfishness and Altruism in Parent-Offspring Coadaptation Min Wu, Jean-Claude Walser, Lei Sun and Mathias Kölliker

SCIENCE ADVANCES | RESEARCH ARTICLE EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY Copyright © 2020 The Authors, some rights reserved; The genetic mechanism of selfishness and altruism exclusive licensee American Association in parent-offspring coadaptation for the Advancement Min Wu1*, Jean-Claude Walser2, Lei Sun3†, Mathias Kölliker1*‡ of Science. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Distributed The social bond between parents and offspring is characterized by coadaptation and balance between altruistic under a Creative and selfish tendencies. However, its underlying genetic mechanism remains poorly understood. Using transcriptomic Commons Attribution screens in the subsocial European earwig, Forficula auricularia, we found the expression of more than 1600 genes License 4.0 (CC BY). associated with experimentally manipulated parenting. We identified two genes, Th and PebIII, each showing evidence of differential coexpression between treatments in mothers and their offspring. In vivo RNAi experiments confirmed direct and indirect genetic effects of Th and PebIII on behavior and fitness, including maternal food provisioning and reproduction, and offspring development and survival. The direction of the effects consistently indicated a reciprocally altruistic function for Th and a reciprocally selfish function for PebIII. Further metabolic pathway analyses suggested roles for Th-restricted endogenous dopaminergic reward, PebIII-mediated chemical communication and a link to insulin signaling, juvenile hormone, and vitellogenin in parent-offspring Downloaded from coadaptation and social evolution. INTRODUCTION manipulations with and without mother-offspring contact, without Parents and offspring influence each other’s behavior and evolutionary detrimental effects on offspring. Females produce one or two clutches http://advances.sciencemag.org/ fitness through reciprocal interactions (1). As an altruistic trait, over their lifetime and provide food (see movie S1) and protection parental care is beneficial to the survival and development of offspring to their young nymphs (8, 9). -

Woolly Apple Aphid Generalist Predator Feeding Behavior Assessed Through Video Observation in an Apple Orchard

J Insect Behav https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-019-09722-z Woolly Apple Aphid Generalist Predator Feeding Behavior Assessed through Video Observation in an Apple Orchard Robert J. Orpet & David W. Crowder & Vincent P. Jones Received: 19 February 2019 /Revised: 21 June 2019 /Accepted: 28 June 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Generalist predators are considered effective larvae and earwigs differ in their feeding behavior in biological control agents in many agroecosystems. the field, and provide new evidence that ants may hinder However, characterizing the behavior of different gen- aphid biological control by antagonizing earwigs. eralist predator species in realistic field settings is diffi- cult due to challenges associated with directly observing Keywords Biological control . Eriosoma lanigerum . predation events in the field. Here we video recorded Forficula auricularia . formicidae . intraguild predation woolly apple aphid (Erisoma lanigerum) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) colonies to directly observe the feeding behavior of their generalist predators during the day Introduction and night. To observe European earwigs (Forficula auricularia) (Dermaptera: Forficulidae), which are Pest consumption in agroecosystems generally increases thought to be key woolly apple aphid predators but were when different predator taxa complement each other by not present at our study location, we released earwigs feeding at different times or in different locations into the study area. Across 1413 h of video recorded (Straub et al. 2008). However, if niche overlap occurs, over 4 weeks, earwigs made the most attacks on woolly intraguild predation can disrupt biological control of apple aphid colonies, but coccinellid larvae spent more pests (Rosenheim 1998;Straubetal.2008). -

Population Dynamics and Integrated Control of the Damson-Hop Aphid Phorodon Humuli (Schrank) on Hops in Spain A

Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA) Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2013 11(2), 505-517 Available online at www.inia.es/sjar ISSN: 1695-971-X http://dx.doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2013112-2968 eISSN: 2171-9292 Population dynamics and integrated control of the damson-hop aphid Phorodon humuli (Schrank) on hops in Spain A. Lorenzana1*, A. Hermoso-de-Mendoza2, M. V. Seco1 and P. A. Casquero1 1 Departamento de Ingeniería y Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad de León. Avda. Portugal, 41. 24071 León, Spain 2 Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias (IVIA). Ctra. Moncada-Náquera, km 4,5. 46113 Moncada (Valencia), Spain Abstract The hop aphid Phorodon humuli (Schrank) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) is a serious pest in most areas where hops are grown. A field trial was performed on a hop yard throughout 2002, 2003 and 2004 in León (Spain) in order to analyse the population development of Phorodon humuli and its natural enemies, as well as to determine the most effective integrated program of insecticide treatments. The basic population development pattern of P. humuli was similar in the three years: the population peaked between mid to late June, and then decreased in late June/early July, rising again and reaching another peak in mid-July, after which it began to decline, rising once more in late August; this last rise is characteristic of Spain and has not been recorded in the rest of Europe. The hop aphid’s main natural enemy found on the leaves was Coccinella septempunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). The multiple regression analysis showed that aphids are positively related with the presence of beetle eggs and mean daily temperatures and negatively related with maximum daily temperature integral above 27°C in plots without insecticide treatment. -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Subgeneric Classification of European

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 878:Phylogenetic 1–22 (2019) relationships and subgeneric classification of EuropeanEphedrus species 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.878.38408 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Phylogenetic relationships and subgeneric classification of European Ephedrus species (Hymenoptera, Braconidae, Aphidiinae) Korana Kocić1, Andjeljko Petrović1, Jelisaveta Čkrkić1, Milana Mitrović2, Željko Tomanović1 1 University of Belgrade-Faculty of Biology, Institute of Zoology. Studentski Trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 Institute for Plant Protection and Environment, Department of Plant Pests, Banatska 33, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Corresponding author: Korana Kocić ([email protected]) Academic editor: K. van Achterberg | Received 21 July 2019 | Accepted 2 September 2019 | Published 7 October 2019 http://zoobank.org/9B51B440-ACFC-4E1A-91EA-32B28554AF56 Citation: Kocić K, Petrović A, Čkrkić J, Mitrović M, Tomanović Ž (2019) Phylogenetic relationships and subgeneric classification of EuropeanEphedrus species (Hymenoptera, Braconidae, Aphidiinae). ZooKeys 878: 1–22. https://doi. org/10.3897/zookeys.878.38408 Abstract In this study two molecular markers were used to establish taxonomic status and phylogenetic relation- ships of Ephedrus subgenera and species distributed in Europe. Fifteen of the nineteen currently known species have been analysed, representing three subgenera: Breviephedrus Gärdenfors, 1986, Lysephedrus Starý, 1958 and Ephedrus Haliday, 1833. The results of analysis of COI and EF1α molecular markers and morphological studies did not support this classification. Three clades separated by the highest genetic distances reported for the subfamily Aphidiinae on intrageneric level. Ephedrus brevis is separated from persicae and plagiator species groups with genetic distances of 19.6 % and 16.3 % respectively, while the distance between persicae and plagiator groups was 20.7 %. -

No Slide Title

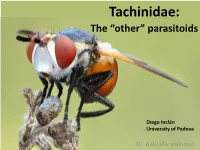

Tachinidae: The “other” parasitoids Diego Inclán University of Padova Outline • Briefly (re-) introduce parasitoids & the parasitoid lifestyle • Quick survey of dipteran parasitoids • Introduce you to tachinid flies • major groups • oviposition strategies • host associations • host range… • Discuss role of tachinids in biological control Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Life cycle of a parasitoid Alien (1979) Life cycle of a parasitoid Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Parasitoid does not kill the host kill its host Insects life cycles Life cycle of a parasitoid Some facts about parasitoids • Parasitoids are diverse (15-25% of all insect species) • Hosts of parasitoids = virtually all terrestrial insects • Parasitoids are among the dominant natural enemies of phytophagous insects (e.g., crop pests) • Offer model systems for understanding community structure, coevolution & evolutionary diversification Distribution/frequency of parasitoids among insect orders Primary groups of parasitoids Diptera (flies) ca. 20% of parasitoids Hymenoptera (wasps) ca. 70% of parasitoids Described Family Primary hosts Diptera parasitoid sp Sciomyzidae 200? Gastropods: (snails/slugs) Nemestrinidae 300 Orth.: Acrididae Bombyliidae 5000 primarily Hym., Col., Dip. Pipunculidae 1000 Hom.:Auchenorrycha Conopidae 800 Hym:Aculeata Lep., Orth., Hom., Col., Sarcophagidae 1250? Gastropoda + others Lep., Hym., Col., Hem., Tachinidae > 8500 Dip., + many others Pyrgotidae 350 Col:Scarabaeidae Acroceridae 500 Arach.:Aranea Hym., Dip., Col., Lep., Phoridae 400?? Isop.,Diplopoda -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000).