STANDARD SAFETY SETTING the STANDARD for SERVICE and SECURITY June 2012 NAVIGATION SPECIAL EDITION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexes to Riverdance Report No 18/2009

Annex 1 QinetiQ report on stability investigation of mv Riverdance COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE MV RIVERDANCE Stability Investigation for MAIB August 2009 Copyright © QinetiQ ltd 2009 COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE List of contents 1 Introduction 7 2 Investigation of the MV RIVERDANCE 8 2.1 MV RIVERDANCE Track 8 2.2 Environmental Conditions in the Area of the Incident 9 2.3 Loading Condition and Stability of MV RIVERDANCE 11 2.4 Stability Book Version 12 2.5 Evaluation of the Stability Book 12 2.6 Vessel loading condition 13 3 MV RIVERDANCE - Scenario Assessments 22 3.1 Prior to the incident 22 3.2 Dynamic Stability of MV RIVERDANCE in Stern Seas 22 3.3 The Turn to Starboard 27 3.4 Cargo Shift Prior to and After the Turn to Starboard 30 3.5 Wind Effects 37 3.6 Other potential contributing factors on the vessel angle following the turn 37 3.7 Combined List and Heel after turn - Cumulative effect of downflooding with cargo shift and wind effects 43 3.8 Potential Transfer of Fluid between Heeling Tanks (13) 47 3.9 The attempted re-floating of MV RIVERDANCE 58 3.10 The most likely sequence of events 59 4 Conclusions 63 4.1 Conclusions 63 5 References / Bibliography 66 6 Abbreviations 67 A Loading Conditions 68 A.1 Lightship 68 A.2 Estimated Load Condition 69 A.3 Plus 10% Cargo 70 A.4 Plus 15% Cargo 71 A.5 VCG Up 72 A.6 VCG Up plus 10% Cargo 73 A.7 VCG Up plus 15% Cargo 74 A.8 Cargo Shifted Up 75 A.9 Cargo Shifted Down 76 A.10 Tank states for all loading conditions 77 7 Initial distribution list 79 Page 4 COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE COMMERCIAL IN CONFIDENCE List of Figures Figure 2-1 - MV RIVERDANCE track 9 Figure 2-2 - Water Depth 10 Figure 2-3 - Most likely cargo positioning 19 Figure 3-1- Parametric roll in regular head seas. -

Branch's Elements of Shipping/Alan E

‘I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in shipping or taking a course where shipping is an important element, for example, chartering and broking, maritime transport, exporting and importing, ship management, and international trade. Using an approach of simple analysis and pragmatism, the book provides clear explanations of the basic elements of ship operations and commercial, legal, economic, technical, managerial, logistical, and financial aspects of shipping.’ Dr Jiangang Fei, National Centre for Ports & Shipping, Australian Maritime College, University of Tasmania, Australia ‘Branch’s Elements of Shipping provides the reader with the best all-round examination of the many elements of the international shipping industry. This edition serves as a fitting tribute to Alan Branch and is an essential text for anyone with an interest in global shipping.’ David Adkins, Lecturer in International Procurement and Supply Chain Management, Plymouth Graduate School of Management, Plymouth University ‘Combining the traditional with the modern is as much a challenge as illuminating operations without getting lost in the fascination of the technical detail. This is particularly true for the world of shipping! Branch’s Elements of Shipping is an ongoing example for mastering these challenges. With its clear maritime focus it provides a very comprehensive knowledge base for relevant terms and details and it is a useful source of expertise for students and practitioners in the field.’ Günter Prockl, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School, Denmark This page intentionally left blank Branch’s Elements of Shipping Since it was first published in 1964, Elements of Shipping has become established as a market leader. -

Chapter 1A Pg 1

METRIC Instructional MANUAL CONTENTS Chapter Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Ship Draft, Trim and Stability Notes 14 3 Draft Survey 30 4 Cargo Deadweight 50 5 Trim and Stability 58 6 Grain Loading 73 7 Rolling Period Test for GM 88 Appendix 94 Draft and Stability Problems and Answers 94 - 1 - CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION PURPOSE 1.1 This Handbook is intended to assist Deck Officers with their loading calculations. Practical solutions are emphasised, and the most common questions about ship loading are answered. 1.2 More detailed knowledge may be obtained from published tomes on the subject which will provide fuller coverage of stability. DESCRIPTION 1.3 Chapter One, Introduction - describes the purpose of the Handbook. There is a summary of the contents of each chapter. An alphabetical listing of abbreviations used, a listing by chapter of formulas, and some recommended materials and equipment for performing ship-loading computations are also included. 1.4 Chapter Two, Ship Draft, Trim and Stability Notes -defines and discusses points and practices which have a practical effect on safe and economic ship loading. 1.5 Chapter Three, Draft Survey - describes in detail, complete with worked examples, the procedure for performing an International Standard Draft Survey. 1.6 Chapter Four, Cargo Deadweight - summarises the main considerations when performing cargo deadweight calculations. Each step in the procedure is then described in detail, complete with worked examples. 1.7 Chapter Five, Trim and stability - summarises the main considerations when performing trim and stability calculations. Each step in the procedures is then described in detail, complete with worked examples. -

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition

SOLAS 2018 Consolidated Edition CHAPTER I GENERAL PROVISIONS PART A-APPLICATION, DEFINITIONS, ETC. Regulation 1 Application* * Refer to MSC-MEPC.5/Circ.8 on Unified interpretation of the application of regulations governed by the building contract date, the keel laying date and the delivery date for the requirements of the SOLAS and MARPOL Conventions. (a) Unless expressly provided otherwise, the present Regulations apply only to ships engaged on international voyages. (b) The classes of ships to which each Chapter applies are more precisely defined, and the extent of the application is shown, in each Chapter. Regulation 2 Definitions For the purpose of the present regulations, unless expressly provided otherwise: (a) Regulations means the regulations contained in the annex to the present Convention. (b) Administration means the Government of the State whose flag the ship is entitled to fly. (c) Approved means approved by the Administration. (d) International voyage means a voyage from a country to which the present Convention applies to a port outside such country, or conversely. (e) A passenger is every person other than: 1 (i) the master and the members of the crew or other persons employed or engaged in any capacity on board a ship on the business of that ship and (ii) a child under one year of age. (f) A passenger ship is a ship which carries more than twelve passengers. (g) A cargo ship is any ship which is not a passenger ship. (h) A tanker is a cargo ship constructed or adapted for the carriage in bulk of liquid cargoes of an inflammable* nature. -

Dangerous Solid Cargoes in Bulk

A selection of articles previously Dangerous solid published by Gard AS cargoes in bulk DRI, nickel and iron ores 3 Contents Carriage of dangerous cargo - Questions to ask before you say yes .............................................. 4 Understanding the different direct reduced iron products ................................................................ 7 Carriage of Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) by Sea - Changes to the IMO Code of Safe Practice for Solid Bulk Cargoes ....................................................................................................... 8 The dangers of carrying Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) .......................................................................... 11 Information required when offered a shipment of Iron fines that may contain DRI (C) ................ 12 Liquefaction of unprocessed mineral ores - Iron ore fines and nickel ore ...................................... 14 Intercargo publishes guide for the safe loading of nickel ore ......................................................... 18 Shifting solid bulk cargoes .................................................................................................................. 19 Cargo liquefaction - An update .......................................................................................................... 22 Cargo liquefaction problems – sinter feed from Brazil ..................................................................... 26 Liquefaction of cargoes of iron ore ................................................................................................... -

Ship Knowledge Questions

Ship Knowledge Questions PUBLISHED BY: All rights reserved. Great care has been taken with the DOKMAR Maritime Publishers BV No part of this publication may be investigation of prior copyright. In P.O.Box 5052 reproduced, stored in a retrieval case of omission the rightful CLaimant 4337RC Vlissingen, The Netherlands. system or transmitted in any form or is requested to inform the publishers. by any means, including electronic, © Copyright 2016, 9th edition mechanical, by photocopy, through Great care has been taken with the Dokmar, Vlissingen, recording or otherwise, without prior compilation of the text. However, mis- The Netherlands written permission of the publisher. takes may occur for which Dokmar accepts no responsibility. ISBN: 978-90-71500-32-9 QUESTIONS 1 For an easy, fun way to help you learn shipping rela- 1 ted terms, download "Ship Knowledge" from the Apple Appstore, or from Google Play and Start. 2 48. What is the sheer? 1 Principal dimensions 49. Why does the sheer in fore and aft ship give the vessel extra reserve buoyancy? 50. What is the camber? 51. What is the rise of floor? 1.1 Definitions 52. What is the bilge radius? 1. What is Length over all? 2. What means length between perpendiculars? 3. What means Loadline? 1.3 Proportions 4. What means Construction Waterline? 53. Name a number of ship's proportions related to the ratio of 5. What means 'moulded dimensions'? vessel main dimensions. 6. What is freeboard? 54. What is a usual L/B-ratio for a freighter? 7. What is a perpendicular? 55. Why is a small L/B-ratio unfavourable for the manoeuvrability? 8. -

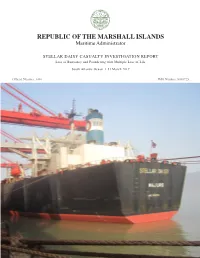

STELLAR DAISY CASUALTY INVESTIGATION REPORT Loss of Buoyancy and Foundering with Multiple Loss of Life

REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Maritime Administrator STELLAR DAISY CASUALTY INVESTIGATION REPORT Loss of Buoyancy and Foundering with Multiple Loss of Life South Atlantic Ocean | 31 March 2017 Official Number: 3486 IMO Number: 9038725 CONDOLENCES The Republic of the Marshall Islands Maritime Administrator offers its sincere condolences to the families and friends of the 22 individuals who perished in the 31 March 2017 casualty. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Republic of the Marshall Islands Maritime Administrator commends the surviving members of the crew of STELLAR DAISY for their dedication to searching for their fellow crewmembers. The Master and crew of SPITHA, and particularly ELPIDA, are also commended for their efforts in searching for and rescuing the surviving members of STELLAR DAISY crew. The Republic of the Marshall Islands Maritime Administrator thanks the marine safety investigation authorities from the Republic of Korea, the Republic of the Philippines, and the Federative Republic of Brazil, which participated as substantially interested States, and Polaris Shipping Co., Ltd., the Korean Register of Shipping, and Vale SA, which were interested parties, for their cooperation. Published by: Republic of the Marshall Islands Maritime Administrator on 19 April 2019 DISCLAIMER In accordance with national and international requirements, the Republic of the Marshall Islands Maritime Administrator (the “Administrator”) conducts marine safety investigations of marine casualties and incidents to promote the safety of life and property at sea and to promote the prevention of pollution. Marine safety investigations conducted by the Administrator do not seek to apportion blame or determine liability. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this Report, the Administrator and its representatives, agents, employees, or affiliates accept no liability for any findings or determinations contained herein, or for any error or omission, alleged to be contained herein. -

DNVGL-RU-SHIP-Pt5ch10 Vessels for Special Operations

RULES FOR CLASSIFICATION Ships Edition October 2015 Part 5 Ship types Chapter 10 Vessels for special operations The content of this service document is the subject of intellectual property rights reserved by DNV GL AS ("DNV GL"). The user accepts that it is prohibited by anyone else but DNV GL and/or its licensees to offer and/or perform classification, certification and/or verification services, including the issuance of certificates and/or declarations of conformity, wholly or partly, on the basis of and/or pursuant to this document whether free of charge or chargeable, without DNV GL's prior written consent. DNV GL is not responsible for the consequences arising from any use of this document by others. The electronic pdf version of this document, available free of charge from http://www.dnvgl.com, is the officially binding version. DNV GL AS FOREWORD DNV GL rules for classification contain procedural and technical requirements related to obtaining and retaining a class certificate. The rules represent all requirements adopted by the Society as basis for classification. © DNV GL AS October 2015 Any comments may be sent by e-mail to [email protected] If any person suffers loss or damage which is proved to have been caused by any negligent act or omission of DNV GL, then DNV GL shall pay compensation to such person for his proved direct loss or damage. However, the compensation shall not exceed an amount equal to ten times the fee charged for the service in question, provided that the maximum compensation shall never exceed USD 2 million. -

OVERALL STABILITY 4.1 External Forces Acting on a Vessel

OVERALL STABILITY 4.1 External Forces Acting on a Vessel In Chapter 4 we will study five areas: 1. The concept of a ship’s Righting Moment (RM), the chief measure of stability. 2. KG and TCG changes and their effects on RM. 3. How Stability is effected by Damage to the Hull using the “Added Weight” method. 4. Effects of a “Free Surface”. 5. Effects of Negative GM on ship stability. 4.2 Internal Righting Moment EXTERNAL FORCES cause a vessel to heel. Recall Force x Distance = Moment – External Moment can be caused by wind pushing on one side of the vessel and water resisting the motion on the other side. – Each distributed force can be resolved into a resultant force vector. The wind acts above the waterline and the water resistance acts below the waterline. Internal Righting Moment MT External upsetting force f Ds Righting Arm G Z WLf F f B FB Water resistance CL Internal Righting Moment The two forces create a couple because they are equal in magnitude, opposite in direction, and not aligned. The couple causes rotation or heeling. The vessel will continue to rotate until it returns to Static Equilibrium (i.e. an Internal Moment is created which is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction). Giving M=0. Internal Righting Moment Internal Forces create a Righting Moment to counter the Upsetting Moment of the External Forces. The two internal forces are the weight of the vessel (s) and the resultant buoyant force (FB). Internal Righting Moment The perpendicular distance between the Weight and the Buoyancy Force vectors is defined as the RIGHTING ARM (GZ). -

Ship Stability Notes & Examples

Ship Stability Notes & Examples To my wife Hilary and our family Ship Stability Notes & Examples Third Edition Kemp & Young Revised by Dr. C. B. Barrass OXFORD AUCKLAND BOSTON JOHANNESBURG MELBOURNE NEW DELHI Butterworth-Heinemann Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 225 Wildwood Avenue, Woburn, MA 01801-2041 A division of Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd First published by Stanford Maritime Ltd 1959 Second edition (metric) 1971 Reprinted 1972, 1974, 1977, 1979, 1982, 1984, 1987 First published by Butterworth-Heinemann 1989 Reprinted 1990, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999 Third edition 2001 P. Young 1971 C. B. Barrass 2001 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, W1P 9HE, England. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0 7506 4850 3 Typeset by Laser Words, Madras, India Printed and bound in Great Britain by Athenaeum Press Ltd, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear Contents Preface ix Useful formulae xi Ship types and general characteristics xv Ship stability – the concept xvii I First Principles 1 Length, mass, force, weight, moment etc. -

Master Yacht (STCW Reg II/2)

Minimum standard of competence for Master Yacht (STCW Reg II/2) Function: Navigation at the management level Competence Knowledge, understanding Methods for Criteria for evaluating and proficiency demonstrating competency competency Plan a voyage Voyage planning and Examination and The equipment, charts and conduct navigation for all conditions assessment of evidence and nautical publications navigation by acceptable methods of obtained from one or more required for the voyage plotting ocean tracks, by of the following: are enumerated and taking into account, appropriate to the safe .1 approved in-service conduct of the voyage e.g.: experience The reasons for the .1 restricted waters .2 approved simulator planned route are training where appropriate supported by facts and .2 meteorological conditions statistical data obtained .3 approved laboratory from relevant sources .3 ice equipment training using: and publications .4 restricted visibility Using: chart catalogues, Positions, courses, charts, nautical .5 traffic separation schemes distances and time publications and ship calculations are correct particulars .6 vessel traffic services (VTS) within accepted accuracy areas standards for navigational equipment .7 areas of extensive tidal effects All potential navigational hazards are Passage Planning accurately identified Appraisal and planning 1 Identify Most Suitable Route – Consult all Relevant Documentation a. Pilot book information: shallow patches, restricted areas, conspicuous landmasses, offshore dangers etc b. set courses on charts, berth to berth, between points of departure and destination c. Prevailing currents and tides (heights and directions) in relevant places d. Reporting areas, VTS and other communication requirements 1 Competence Knowledge, understanding Methods for Criteria for evaluating and proficiency demonstrating competency competency e. Pilotage area requirements f. -

Tasports Ports Procedures Manual 3.4 MB

Division: Marine Services Tasmanian Ports Corporation Ports Procedures Manual June 2019 PORTS PROCEDURES MANUAL Page 1 of 66 PRINTED COPIES ARE UNCONTROLLED Division: Marine Services This Ports Procedures Manual is authorised by the TasPorts Chief Executive Officer. The consultation process prior to approval has included recommendations from the TasPorts Harbour Master, Marine Pilots and Marine and Safety Tasmania. Chief Executive Officer Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty Ltd. PORTS PROCEDURES MANUAL Page 2 of 66 PRINTED COPIES ARE UNCONTROLLED Division: Marine Services Revision No Date Revision Updated by 1 12.5.11 “Passage” section for each port amended by C. Black replacing Port Limit with Point of No Return. 2 17.5.11 Removed “Solas Regulation 17 Chapter 5” from C. Black reference list as Solas is not mentioned in the document. 3 15.6.11 Page 26, Section 8.1.10, para (a) bridge curfew C. Black times. Revised afternoon times to “1330 and 1800” on advice from DIER. 4 4.10.11 Page 47, Section 8.4.8 Berth Depths. Revised C. Black depths entered following hydrographic survey. 5 14.05.12 Page 33, Table 8.2.1 – Pilot Boarding Times. C. Black Amended to reflect new parameters resulting from pilot boarding ground being move one mile to seaward. 6 22.6.12 Page 46, Section 8.4.6 - Revised entry C. Black parameter table for Devonport. 7 29.8.13 Page 36, Bell Bay depths amended following C. Black hydrographic survey in June 2013. 8 7.10.13 Appendix 1 added – Shows emergency beaching C. Black and anchoring positions in Tamar River.