Jenny-Brooke Condon*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Office of the Attorney General the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell

February 3, 2010 The Honorable Mitch McConnell United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator McConnell: I am writing in reply to your letter of January 26, 2010, inquiring about the decision to charge Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab with federal crimes in connection with the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 near Detroit on December 25, 2009, rather than detaining him under the law of war. An identical response is being sent to the other Senators who joined in your letter. The decision to charge Mr. Abdulmutallab in federal court, and the methods used to interrogate him, are fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole, as implemented for many years by Administrations of both parties. Those policies and practices, which were not criticized when employed by previous Administrations, have been and remain extremely effective in protecting national security. They are among the many powerful weapons this country can and should use to win the war against al-Qaeda. I am confident that, as a result of the hard work of the FBI and our career federal prosecutors, we will be able to successfully prosecute Mr. Abdulmutallab under the federal criminal law. I am equally confident that the decision to address Mr. Abdulmutallab's actions through our criminal justice system has not, and will not, compromise our ability to obtain information needed to detect and prevent future attacks. There are many examples of successful terrorism investigations and prosecutions, both before and after September 11, 2001, in which both of these important objectives have been achieved -- all in a manner consistent with our law and our national security interests. -

Tom Eagleton and the "Curse to Our Constitution"

TOM EAGLETON AND THE “CURSE TO OUR CONSTITUTION” By William H. Freivogel Director, School of Journalism, Southern Illinois University Carbondale Associate Professor, Paul Simon Public Policy Institute This paper is scheduled for publication in St. Louis University Law Journal, Volume 52, honoring Sen. Eagleton. Introduction: If my friend Tom Eagleton had lived a few more months, I’m sure he would have been amazed – and amused in a Tom Eagleton sort of way - by the astonishing story of Alberto Gonzales’ late night visit to John Aschroft’s hospital bed in 2004 to persuade the then attorney general to reauthorize a questionable intelligence operation related to the president’s warrantless wiretapping program. No vignette better encapsulates President George W. Bush’s perversion of the rule of law. Not since the Saturday Night Massacre during Watergate has there been a moment when a president’s insistence on having his way resulted in such chaos at the upper reaches of the Justice Department. James Comey, the deputy attorney general and a loyal Republican, told Congress in May, 2007 how he raced to George Washington hospital with sirens blaring to beat Gonzeles to Ashcroft’s room.1 Comey had telephoned FBI Director Robert S. Mueller to ask that he too come to the hospital to back up the Justice Department’s view that the president’s still secret program should not be reauthorized as it then operated.2 Ashcroft, Comey and Mueller held firm in the face of intense pressure from White House counsel Gonzales and Chief of Staff Andrew Card. Before the episode was over, the three were on the verge of tendering their resignations if the White House ignored their objections; the resignations were averted by some last-minute changes in the program – changes still not public.3 Before Eagleton’s death, he and I had talked often about Bush and Ashcroft’s overzealous leadership in the war on terrorism. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

Ohio Terrorism N=30

Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Advanced Technical Intelligence Center ABC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” “Political, Religious, or Ideological Goals” The Research… #520 Charged (2001-2018) • Betim Kaziu • Abid Naseer • Ali Mohamed Bagegni • Bilal Abood • Adam Raishani (Saddam Mohamed Raishani) • Ali Muhammad Brown • Bilal Mazloum • Adam Dandach • Ali Saleh • Bonnell (Buster) Hughes • Adam Gadahn (Azzam al-Amriki) • Ali Shukri Amin • Brandon L. Baxter • Adam Lynn Cunningham • Allen Walter lyon (Hammad Abdur- • Brian Neal Vinas • Adam Nauveed Hayat Raheem) • Brother of Mohammed Hamzah Khan • Adam Shafi • Alton Nolen (Jah'Keem Yisrael) • Bruce Edwards Ivins • Adel Daoud • Alwar Pouryan • Burhan Hassan • Adis Medunjanin • Aman Hassan Yemer • Burson Augustin • Adnan Abdihamid Farah • Amer Sinan Alhaggagi • Byron Williams • Ahmad Abousamra • Amera Akl • Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax • Ahmad Hussam Al Din Fayeq Abdul Aziz (Abu Bakr • Amiir Farouk Ibrahim • Carlos Eduardo Almonte Alsinawi) • Amina Farah Ali • Carlos Leon Bledsoe • Ahmad Khan Rahami • Amr I. Elgindy (Anthony Elgindy) • Cary Lee Ogborn • Ahmed Abdel Sattar • Andrew Joseph III Stack • Casey Charles Spain • Ahmed Abdullah Minni • Anes Subasic • Castelli Marie • Ahmed Ali Omar • Anthony M. Hayne • Cedric Carpenter • Ahmed Hassan Al-Uqaily • Antonio Martinez (Muhammad Hussain) • Charles Bishop • Ahmed Hussein Mahamud • Anwar Awlaki • Christopher Lee Cornell • Ahmed Ibrahim Bilal • Arafat M. -

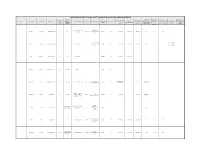

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

ARTICLE: Sentencing Terrorist Crimes

ARTICLE: Sentencing Terrorist Crimes 2014 Reporter 75 Ohio St. L.J. 477 * Length: 10798 words Author: WADIE E. SAID * * Associate Professor, University of South Carolina School of Law. Thanks are due to Amna Akbar, Jack Chin, Tommy Crocker, Nirej Sekhon, Shirin Sinnar, and Spearit for their helpful comments on this Article. Special thanks to Ryan Grover for his excellent research assistance. All errors are my own. Highlight The legal framework behind the sentencing of individuals convicted of committing terrorist crimes has received little scholarly attention, even with the proliferation of such prosecutions in the eleven years following the attacks of September 11, 2001. This lack of attention is particularly striking in light of the robust and multifaceted scholarship that deals with the challenges inherent in criminal sentencing more generally, driven in no small part by the comparatively large number of sentencing decisions issued by the United States Supreme Court over the past thirteen years. Reduced to its essence, the Supreme Court's sentencing jurisprudence requires district courts to make no factual findings that raise a criminal penalty over the statutory maximum, other than those found by a jury or admitted by the defendant in a guilty plea. Within those parameters, however, the Court has made clear that such sentences are entitled to a strong degree of deference by courts of review. Historically, individuals convicted of committing crimes involving politically motivated violence/terrorism were sentenced under ordinary criminal statutes, as theirs were basically crimes of violence. Even when the law shifted to begin to recognize certain crimes as terrorist in nature--airplane hijacking being the prime example-- sentencing remained relatively uncontroversial from a legal perspective, since the underlying conduct being punished was violent at its core. -

Attorney General Letter on Detention, Interrogation of Umar Farouk

February 3, 2010 The Honorable Mitch McConnell United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator McConnell: I am writing in reply to your letter of January 26, 2010, inquiring about the decision to charge Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab with federal crimes in connection with the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 near Detroit on December 25, 2009, rather than detaining him under the law of war. An identical response is being sent to the other Senators who joined in your letter. The decision to charge Mr. Abdulmutallab in federal court, and the methods used to interrogate him, are fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole, as implemented for many years by Administrations of both parties. Those policies and practices, which were not criticized when employed by previous Administrations, have been and remain extremely effective in protecting national security. They are among the many powerful weapons this country can and should use to win the war against al-Qaeda. I am confident that, as a result of the hard work of the FBI and our career federal prosecutors, we will be able to successfully prosecute Mr. Abdulmutallab under the federal criminal law. I am equally confident that the decision to address Mr. Abdulmutallab's actions through our criminal justice system has not, and will not, compromise our ability to obtain information needed to detect and prevent future attacks. There are many examples of successful terrorism investigations and prosecutions, both before and after September 11, 2001, in which both of these important objectives have been achieved -- all in a manner consistent with our law and our national security interests. -

Terrorist Trial Report Card 2001-2009

Center on Law and Security, New York University School of Law Terrorist Trial Report Card: September 11, 2001-September 11, 2009 January 2010 Acknowledgments Executive Director of the Center on Law and Security / Editor in Chief Karen J. Greenberg Director of Research/Writer Francesca Laguardia Editor Jeff Grossman Research Jessica Alvarez, Gayle Argon, Daniel Peter Burgess, Laura C. Carey, Andrea Lee Clowes, Casey Doherty, Meredith J. Fortin, Alice Goldman, Matt Golubjatnikov, Isabelle Kinsolving, Tracy A. Lundquist, Adam Maltz, Robert Miller, Lea Newfarmer, Robert E. O’Leary, Jason Porta, Meredythe M. Ryan, Dominic A. Saglibene, Alexandra Ross Schwartz, Moses Sternstein, Nancy Sul, and Jonathan Weinblatt Designer Wendy Bedenbaugh Senior Fellow for Legal Affairs Joshua L. Dratel Faculty Co-Directors of the Center on Law and Security David Golove, Stephen Holmes, Richard H. Pildes, and Samuel J. Rascoff Special thanks to Barton Gellman, CLS Research Fellow. In its formative years, the Terrorist Trial Report Card was supervised consecutively by Andrew Peterson, Daniel Freifeld, and Michael Price. Our gratitude for their work is immeasurable. Thanks also to Nicole Bruno and David Tucker. The Center on Law and Security New York University School of Law 110 West Third Street • New York, NY 10012 • 212-992-8854 • [email protected] Copyright ©2010 by the Center on Law and Security www.lawandsecurity.org i The Terrorist Trial Report Card, 2001-2009 tudying the full eight years of post-9/11 federal terrorism prosecutions, the Center on Law and SSecurity has assembled a massive relational database, a resource that exists nowhere else. Periodically we have reached into the growing data set and pulled out snapshots of the most illuminating trends. -

Would-Be Warriors: Incidents of Jihadist Terrorist Radicalization in the United States Since September 11, 2001

CORPORATION THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation occasional paper series. RAND occasional papers may include an informed perspective on a timely policy issue, a discussion of new research methodologies, essays, a paper presented at a conference, a conference summary, or a summary of work in progress. All RAND occasional papers undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Saudi Arabia's Troubling Educational Curriculum” Hon

1 Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade “Saudi Arabia's Troubling Educational Curriculum” Hon. Frank Wolf- Written Testimony July 19, 2017 Mr. Chairman, Members of the Committee, thank you for having this hearing regarding concerns about Saudi Arabia’s educational curriculum and the rise of radicalization. I have shared these same concerns for many years when I served in the House and since joining the Wilberforce Initiative in 2015, and it is my hope that the U.S. government will continue to monitor and assess the educational materials that the government of Saudi Arabia publishes in order to ensure that they do not incite further violence, hatred and radicalism in the United States as well as abroad. We should also consider solutions that ensure other countries that may produce similar intolerant and extreme content is addressed. The issue of Saudi Arabia’s educational curriculum as a means of promoting intolerance and inspiring terrorism is not a new one. This topic hit close to home in 2003, when Ahmed Omar Abu Ali was arrested while in class at the Islamic University of Medina, for an attempted plot to assassinate President Bush. Before attending university in Medina, Mr. Abu Ali attended and was the valedictorian at a high school which was located here in northern Virginia, the Islamic Saudi Academy. Mr. Abu Ali was ultimately sentenced to life in prison and is currently serving out his sentence in the supermax in Colorado. The reason I would like to highlight this particular case in particular is due to the fact that concerns were then raised regarding the educational material being used by the Islamic Saudi Academy.