ARTICLE: Sentencing Terrorist Crimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYC News Summer 2014

NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD New York City News NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD – NYC CHAPTER SUMMER 2014 Mass Incarceration Launches Parole Preparation Project The NLG-NYC Mass Incarceration six to nine months. date to look at risk, rehabilitation, readiness Committee (MIC) has had an exciting sum- Volunteers will collaborate with parole for release, and an array of other factors mer! On June 11th, we held a training for applicants to gather necessary documentation when determining an individual’s eligibility volunteers interested in participating in for upcoming parole hearings, and work with for release, disproportionately emphasizing the Parole Preparation Project. The Project them on practicing for the actual interview. the seriousness of an individual’s crime of aims to pair volunteers (law students, social Volunteers will also support volunteers in conviction. The results are both unlawful workers, family and friends of incarcerated soliciting meaningful letters of support from and unethical. This flawed system weakens persons among others) with individuals who friends, family, co-workers, and the Project morale among those who have worked hard face long prison sentences and have been will write letters of support as well. to rehabilitate themselves only to find their repeatedly denied parole. Approximately 40 The Project exists in response to our efforts go unrewarded as they are repeatedly people attended the training, most commit- broken New York State parole system. The denied release. ting to working on the project over the next Board of Parole routinely violates its man- In addition, in part because of parole denials, nearly 9,000 elderly persons remain incarcerated throughout New York. Though these individuals recidivate at the low rate INSIDE THIS ISSUE: of approximately 3%, and many suffer from COMMITTEE UPDATES ................................................................................................ -

Office of the Attorney General the Honorable Mitch Mcconnell

February 3, 2010 The Honorable Mitch McConnell United States Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Senator McConnell: I am writing in reply to your letter of January 26, 2010, inquiring about the decision to charge Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab with federal crimes in connection with the attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253 near Detroit on December 25, 2009, rather than detaining him under the law of war. An identical response is being sent to the other Senators who joined in your letter. The decision to charge Mr. Abdulmutallab in federal court, and the methods used to interrogate him, are fully consistent with the long-established and publicly known policies and practices of the Department of Justice, the FBI, and the United States Government as a whole, as implemented for many years by Administrations of both parties. Those policies and practices, which were not criticized when employed by previous Administrations, have been and remain extremely effective in protecting national security. They are among the many powerful weapons this country can and should use to win the war against al-Qaeda. I am confident that, as a result of the hard work of the FBI and our career federal prosecutors, we will be able to successfully prosecute Mr. Abdulmutallab under the federal criminal law. I am equally confident that the decision to address Mr. Abdulmutallab's actions through our criminal justice system has not, and will not, compromise our ability to obtain information needed to detect and prevent future attacks. There are many examples of successful terrorism investigations and prosecutions, both before and after September 11, 2001, in which both of these important objectives have been achieved -- all in a manner consistent with our law and our national security interests. -

Jenny-Brooke Condon*

CONDON_MACRO (8-25-08) 8/25/2008 10:31:18 AM EXTRATERRITORIAL INTERROGATION: THE POROUS BORDER BETWEEN TORTURE AND U.S. CRIMINAL TRIALS Jenny-Brooke Condon∗ I. INTRODUCTION The conviction of Ahmed Omar Abu Ali, a twenty-two-year-old U.S. citizen from Virginia, for conspiring to commit terrorist attacks within the United States1 exposes a potential crack in a long- assumed bulwark of U.S. constitutional law: that confessions obtained by torture will not be countenanced in U.S. criminal trials.2 ∗ Visiting Clinical Professor, Seton Hall University School of Law. The author served on the legal team representing Ahmed Omar Abu Ali in his habeas corpus petition filed against the United States while he was detained in Saudi Arabia, and contributed to the defense in his subsequent criminal case. The author is grateful to Seton Hall Law School and Kathleen Boozang, in particular, for generous support of this project. She would also like to thank the following people for their insightful comments on previous drafts: Baher Azmy, Elizabeth Condon, Edward Hartnett, and Lori Nessel. She thanks Sheik Shagaff, Abdolreza Mazaheri, and Katherine Christodoloutos for their excellent work as research assistants. 1. See News Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice (Nov. 22, 2005), available at http://www.usdoj.gov/usao/vae/Pressreleases/2005/1105.html (last visited Feb. 13, 2008) (noting that a jury in Eastern District of Virginia found Abu Ali guilty on November 22, 2005 of nine counts, including conspiracy to provide material support and resources to al Qaeda, providing material support to terrorists, conspiracy to assassinate the president of the United States, and conspiracy to commit air piracy and to destroy aircraft). -

Tom Eagleton and the "Curse to Our Constitution"

TOM EAGLETON AND THE “CURSE TO OUR CONSTITUTION” By William H. Freivogel Director, School of Journalism, Southern Illinois University Carbondale Associate Professor, Paul Simon Public Policy Institute This paper is scheduled for publication in St. Louis University Law Journal, Volume 52, honoring Sen. Eagleton. Introduction: If my friend Tom Eagleton had lived a few more months, I’m sure he would have been amazed – and amused in a Tom Eagleton sort of way - by the astonishing story of Alberto Gonzales’ late night visit to John Aschroft’s hospital bed in 2004 to persuade the then attorney general to reauthorize a questionable intelligence operation related to the president’s warrantless wiretapping program. No vignette better encapsulates President George W. Bush’s perversion of the rule of law. Not since the Saturday Night Massacre during Watergate has there been a moment when a president’s insistence on having his way resulted in such chaos at the upper reaches of the Justice Department. James Comey, the deputy attorney general and a loyal Republican, told Congress in May, 2007 how he raced to George Washington hospital with sirens blaring to beat Gonzeles to Ashcroft’s room.1 Comey had telephoned FBI Director Robert S. Mueller to ask that he too come to the hospital to back up the Justice Department’s view that the president’s still secret program should not be reauthorized as it then operated.2 Ashcroft, Comey and Mueller held firm in the face of intense pressure from White House counsel Gonzales and Chief of Staff Andrew Card. Before the episode was over, the three were on the verge of tendering their resignations if the White House ignored their objections; the resignations were averted by some last-minute changes in the program – changes still not public.3 Before Eagleton’s death, he and I had talked often about Bush and Ashcroft’s overzealous leadership in the war on terrorism. -

Translator, Traitor: a Critical Ethnography of a U.S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2014 Translator, traitor: A critical ethnography of a U.S. terrorism trial Maya Hess Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/226 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] TRANSLATOR, TRAITOR: A CRITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A U.S. TERRORISM TRIAL by MAYA HESS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 MAYA HESS All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Diana Gordon ______________________ _____________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Deborah Koetzle ______________________ _____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Susan Opotow __________________________________________ David Brotherton __________________________________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract TRANSLATOR, TRAITOR: A CRITICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A U.S. TERRORISM TRIAL by Maya Hess Adviser: Professor Diana Gordon Historically, the role of translators and interpreters has suffered from multiple misconceptions. In theaters of war, these linguists are often viewed as traitors and kidnapped, tortured, or killed; if they work in the terrorism arena, they may be prosecuted and convicted as terrorist agents. -

Conference Program

First Class Mail U.S. Postage SCHOOL OF LAW PAID 121 Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York 11549-1210 Hofstra University Sunday, Monday and Tuesday October 14, 15 and 16, 2007 Conference Director Professor Roy D. Simon Conference Coordinator Dawn Marzella 7 0 / 9 : PROGRAM 0 9 3 7 LEGAL ETHICS: LAWYERING AT THE EDGE UNPOPULAR CLIENTS, DIFFICULT CASES, ZEALOUS ADVOCATES Stuart Rabinowitz Nora V. Demleitner Roy D. Simon President and Andrew M. Boas Interim Dean and Professor of Law Howard Lichtenstein Distinguished and Mark L. Claster Distinguished Hofstra Law School Professor of Legal Ethics Professor of Law, Hofstra University Hofstra Law School Conference Director KEYNOTE ADDRESS BANQUET ADDRESS Michael E. Tigar Gerald B. Lefcourt Research Professor of Law, Washington College of Law, Law Offices of Gerald B. Lefcourt Visiting Professor, Duke Law School New York, NY Professeur Invite, Universite Paul Cezanne CONFERENCE SPEAKERS Lonnie T. Brown, Jr. Glenda Grace Andrew Perlman Associate Professor of Law Visiting Assistant Professor Associate Professor University of Georgia School of Law Hofstra Law School Suffolk University Law School Raymond Brown Jeanne P. Gray Burnele V. Powell Attorney, Greenbaum, Rowe, Smith & Davis Director, Center for Professional Responsibility Miles and Ann Loadholt Professor of Law Woodbridge, NJ American Bar Association University of South Carolina School of Law Alafair S. Burke Bruce Green Roy D. Simon Associate Professor of Law Stein Professor of Law, Fordham University Howard Lichtenstein Distinguished Professor Hofstra Law School School of Law of Legal Ethics, Hofstra Law School James Farragher Campbell Joel Hirschhorn Abbe Smith Attorney, Campbell, DeMetrick & Jacobo Attorney, Hirschhorn & Bieber P.A . -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

'Health-Care Reform' Aims to Cut Social Wage

· AUSTRALIA $1.50 · CANADA $1.25 · FRANCE 1.00 EURO · NEW ZEALAND $1.50 · SWEDEN KR10 · UK £.50 · U.S. $1.00 INSIDE Venezuela Int’l Book Fair spreads access to culture — PAGE 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 73/NO. 46 NOVEMBER 30, 2009 Foreclosures ‘Health-care reform’ Washington mount as aims to cut social wage prepares capitalist Bill imposes fines for those without plans new moves crisis deepens against Iran BY BRIAN WILLIAMS BY CINDY JAQUITH Despite government programs at- November 16—As relations be- tempting to stem the crisis in the tween Washington and Tehran de- capitalist housing market, foreclo- teriorate, the Iranian government is sures continue to rise. The number shifting its tone on President Barack hit a record high in the third quarter Obama, whose election it welcomed. with more than 937,000 filings. So far Moscow, meanwhile, has signaled its this year 3.8 million notices of default willingness to back further actions have been filed, according to Moody’s against Iran if it continues to enrich Economy.com. uranium for its nuclear program. The crisis goes far beyond those Washington and the imperialist who have taken out subprime mort- powers in Europe have demanded gage loans, which require no money Tehran cease enriching uranium, down but have interest rate payments charging it is doing so to build an that increase. Millions who had signed atomic bomb. Tehran denies this, say- up for adjustable rate mortgages AP Photo/Paul Beaty ing it will use the uranium as fuel for (ARM) are facing similar prospects Crowded emergency room at Stroger Hospital in Chicago July 30. -

Ohio Terrorism N=30

Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Advanced Technical Intelligence Center ABC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” “Political, Religious, or Ideological Goals” The Research… #520 Charged (2001-2018) • Betim Kaziu • Abid Naseer • Ali Mohamed Bagegni • Bilal Abood • Adam Raishani (Saddam Mohamed Raishani) • Ali Muhammad Brown • Bilal Mazloum • Adam Dandach • Ali Saleh • Bonnell (Buster) Hughes • Adam Gadahn (Azzam al-Amriki) • Ali Shukri Amin • Brandon L. Baxter • Adam Lynn Cunningham • Allen Walter lyon (Hammad Abdur- • Brian Neal Vinas • Adam Nauveed Hayat Raheem) • Brother of Mohammed Hamzah Khan • Adam Shafi • Alton Nolen (Jah'Keem Yisrael) • Bruce Edwards Ivins • Adel Daoud • Alwar Pouryan • Burhan Hassan • Adis Medunjanin • Aman Hassan Yemer • Burson Augustin • Adnan Abdihamid Farah • Amer Sinan Alhaggagi • Byron Williams • Ahmad Abousamra • Amera Akl • Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax • Ahmad Hussam Al Din Fayeq Abdul Aziz (Abu Bakr • Amiir Farouk Ibrahim • Carlos Eduardo Almonte Alsinawi) • Amina Farah Ali • Carlos Leon Bledsoe • Ahmad Khan Rahami • Amr I. Elgindy (Anthony Elgindy) • Cary Lee Ogborn • Ahmed Abdel Sattar • Andrew Joseph III Stack • Casey Charles Spain • Ahmed Abdullah Minni • Anes Subasic • Castelli Marie • Ahmed Ali Omar • Anthony M. Hayne • Cedric Carpenter • Ahmed Hassan Al-Uqaily • Antonio Martinez (Muhammad Hussain) • Charles Bishop • Ahmed Hussein Mahamud • Anwar Awlaki • Christopher Lee Cornell • Ahmed Ibrahim Bilal • Arafat M. -

More Than Just a Few" Bad Apples

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 8-30-2004 Resist Newsletter, July-Aug 2004 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, July-Aug 2004" (2004). Resist Newsletters. 364. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/364 Inside: Resisting Prison and Military Abuse ISSN 0897-2613 • Vol. 13 #6 A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority July/August 2004 More Than Just a Few "Bad Apples" Confronting Prison Problems in Iraq and in the US Zimbardo had students play the roles of ROSEBRAZ guards and prisoners. The study had to be halted after only a few days when the ondemning the abuse of Iraqi pris "guards" began to abuse their fellow stu oners as "fundamentallyun-Ameri dent "prisoners." In a recent Boston Globe Ccan," Donald Rumsfeld ignores the editorial (May 9, 2004) comparing his strikingly similar circumstances facing two experiment's finding with the abuses in million US prisoners. Abu Ghraib, Zimbardo wrote: While Congress, the military-and pun Some of the necessary ingredients [ for dits alike argue that the Abu Ghraib pho stirring human nature in negative direc tos do not depict conditions in American tions] are: diffusion of responsibility, prisons, they forget that a few months be anonymity, dehumanization, peers who fore atrocities were caught on tape at Abu model harmful behavior, bystanders who. Ghraib, we watched our own videotape of A banner depicting abuse at Abu Ghraib do not intervene, and a setting of power guards at the California Youth Authority prison spans a Los Angeles overpass. -

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

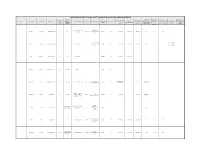

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no.