The Aristoxenian Theory of Musical Rhythm Cambridge University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilson Area School District Planned Course Guide

Board Approved April 2018 Wilson Area School District Planned Course Guide Title of planned course: Music Theory Subject Area: Music Grade Level: 9-12 Course Description: Students in Music Theory will learn the basics and fundamentals of musical notation, rhythmic notation, melodic dictation, and harmonic structure found in Western music. Students will also learn, work on, and develop aural skills in respect to hearing and notating simple melodies, intervals, and chords. Students will also learn how to analyze a piece of music using Roman numeral analysis. Students will be expected to complete homework outside of class and will be graded via tests, quizzes, and projects. Time/Credit for this Course: 3 days a week / 0.6 credit Curriculum Writing Committee: Jonathan Freidhoff and Melissa Black Curriculum Map August: ● Week 1, Unit 1 - Introduction to pitch September: ● Week 2, Unit 1 - The piano keyboard ● Week 3, Unit 1 - Reading pitches from a score ● Week 4, Unit 1 - Dynamic markings ● Week 5, Unit 1 - Review October: ● Week 6, Unit 1 - Test ● Week 7, Unit 2 - Dividing musical time ● Week 8, Unit 2 - Rhythmic notation for simple meters ● Week 9, Unit 2 - Counting rhythms in simple meters November: ● Week 10, Unit 2 - Beat units other than the quarter note and metrical hierarchy ● Week 11, Unit 2 - Review ● Week 12, Unit 2 - Test ● Week 13, Unit 4 - Hearing compound meters and meter signatures December: ● Week 14, Unit 4 - Rhythmic notation in compound meters ● Week 15, Unit 4 - Syncopation and mixing beat divisions ● Week -

Children's Perceptions of Anacrusis Patterns Within Songs

----------------------Q: B ; ~~ett, P. D. (1992). Children's perceptions of anacrusis.......... patterns within songs.~ Texas.... Music Education Research. T. Tunks, Ed., 1-7. Texas Music Education Research - 1990 1 Children's Perceptions of Anacrusis Patterns within Songs Peggy D. Bennett The University of Texas at Arlington In order to help children become musically literate, music teachers have reduced the complexity of musical sound into manageable units or patterns for study. Usually, these patterns are then arranged into a sequence that presumes level of difficulty, and educators lead children through a curriculum based on a progression of patterns "from simple to complex." This practice of using a sequential, "patterned" approach to elementary music education in North America was embraced in 'the 1960's and 1970's when the methodologies of Hungarian, Zoltan Kodaly, and German, Carl Orff, were imported and introduced to American teachers, Touting the "sound before symbol" approach, these methods, for many teachers, replaced the notion of training students to recognize symbols, then to perform the sounds the symbols represented. For many teachers of young children, this era of imported methods reversed the way they taught music, and the organization of music into patterns for study was a monumental aspect of these changes. A "pattern" approach to music education is supported by speech and brain research which indicates that, even when iteJ:t1s are not grouped, individuals naturally process information by organizing it into patterns for retention and recall (Neisser, 1967; Buschke, 1976; Miller, 1956; Glanzer, 1976). Similar processing occurs when musical stimuli are presented (Cooper & Meyer, 1960; Mursell, 1937; Lerdahl & lackendoff, 1983, p. -

Some Problems in Prosody

1903·] Some Problems in Prosody. 33 ARTICLE III. SOME PROBLEMS IN PROSODY. BY PI10PlCSSOI1 R.aBUT W. KAGOUN, PR.D. IT has been shown repeatedly, in the scientific world, that theory must be supplemented by practice. In some cases, indeed, practice has succeeded in obtaining satisfac tory results after theory has failed. Deposits of Urate of Soda in the joints, caused by an excess of Uric acid in the blood, were long held to be practically insoluble, although Carbonate of Lithia was supposed to have a solvent effect upon them. The use of Tetra·Ethyl-Ammonium Hydrox ide as a medicine, to dissolve these deposits and remove the gout and rheumatism which they cause, is said to be due to some experiments made by Edison because a friend of his had the gout. Mter scientific men had decided that electric lighting could never be made sufficiently cheap to be practicable, he discovered the incandescent lamp, by continuing his experiments in spite of their ridicule.1 Two young men who "would not accept the dictum of the authorities that phosphorus ... cannot be expelled from iron ores at a high temperature, ... set to work ... to see whether the scientific world had not blundered.'" To drive the phosphorus out of low-grade ores and convert them into Bessemer steel, required a "pot-lining" capable of enduring 25000 F. The quest seemed extraordinary, to say the least; nevertheless the task was accomplished. This appears to justify the remark that "Thomas is our modem Moses";8 but, striking as the figure is, the young ICf. -

The Rhythm of the Gods' Voice. the Suggestion of Divine Presence

T he Rhythm of the Gods’ Voice. The Suggestion of Divine Presence through Prosody* E l ritmo de la voz de los dioses. La sugerencia de la presencia divina a través de la prosodia Ronald Blankenborg Radboud University Nijmegen [email protected] Abstract Resumen I n this article, I draw attention to the E ste estudio se centra en la meticulosidad gods’ pickiness in the audible flow of de los dioses en el flujo audible de sus expre- their utterances, a prosodic characteris- siones, una característica prosódica del habla tic of speech that evokes the presence of que evoca la presencia divina. La poesía hexa- the divine. Hexametric poetry itself is the métrica es en sí misma el lenguaje de la per- * I want to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of ARYS for their suggestions and com- ments. https://doi.org/10.20318/arys.2020.5310 - Arys, 18, 2020 [123-154] issn 1575-166x 124 Ronald Blankenborg language of permanency, as evidenced by manencia, como pone de manifiesto la litera- wisdom literature, funereal and dedicatory tura sapiencial y las inscripciones funerarias inscriptions: epic poetry is the embedded y dedicatorias: la poesía épica es el lenguaje direct speech of a goddess. Outside hex- directo integrado de una diosa. Más allá de ametric poetry, the gods’ special speech la poesía hexamétrica, el habla especial de los is primarily expressed through prosodic dioses es principalmente expresado mediante means, notably through a shift in rhythmic recursos prosódicos, especialmente a través profile. Such a shift deliberately captures, de un cambio en el perfil rítmico. -

Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register

proceedings of the British Academy, 93.21-93 Poetic Diction, Poetic Discourse and the Poetic Register R. G. G. COLEMAN Summary. A number of distinctive characteristics can be iden- tified in the language used by Latin poets. To start with the lexicon, most of the words commonly cited as instances of poetic diction - ensis; fessus, meare, de, -que. -que etc. - are demonstrably archaic, having been displaced in the prose register. Archaic too are certain grammatical forms found in poetry - e.g. auldi, gen. pl. superum, agier, conticuere - and syntactic constructions like the use of simple cases for pre- I.positional phrases and of infinitives instead of the clausal structures of classical prose. Poets in all languages exploit the linguistic resources of past as well as present, but this facility is especially prominent where, as in Latin, the genre traditions positively encouraged imitatio. Some of the syntactic character- istics are influenced wholly or partly by Greek, as are other ingredients of the poetic register. The classical quantitative metres, derived from Greek, dictated the rhythmic pattern of the Latin words. Greek loan words and especially proper names - Chaoniae, Corydon, Pyrrha, Tempe, Theseus, Zephym etc. -brought exotic tones to the aural texture, often enhanced by Greek case forms. They also brought an allusive richness to their contexts. However, the most impressive charac- teristics after the metre were not dependent on foreign intrusion: the creation of imagery, often as an essential feature of a poetic argument, and the tropes of semantic transfer - metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche - were frequently deployed through common words. In fact no words were too prosaic to appear in even the highest poetic contexts, always assuming their metricality. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

1 Reading Athenaios' Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition And

Reading Athenaios’ Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo: Critical Edition and Commentaries DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Corey M. Hackworth Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Fritz Graf, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Carolina López-Ruiz 1 Copyright by Corey M. Hackworth 2015 2 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the Epigraphical Hymn to Apollo that was found at Delphi in 1893, and since attributed to Athenaios. It is believed to have been performed as part of the Athenian Pythaïdes festival in the year 128/7 BCE. After a brief introduction to the hymn, I provide a survey and history of the most important editions of the text. I offer a new critical edition equipped with a detailed apparatus. This is followed by an extended epigraphical commentary which aims to describe the history of, and arguments for and and against, readings of the text as well as proposed supplements and restorations. The guiding principle of this edition is a conservative one—to indicate where there is uncertainty, and to avoid relying on other, similar, texts as a resource for textual restoration. A commentary follows, which traces word usage and history, in an attempt to explore how an audience might have responded to the various choices of vocabulary employed throughout the text. Emphasis is placed on Athenaios’ predilection to utilize new words, as well as words that are non-traditional for Apolline narrative. The commentary considers what role prior word usage (texts) may have played as intertexts, or sources of poetic resonance in the ears of an audience. -

Power Tab Editor ❍ Appendix B - FAQ - a Collection of Frequently Asked Questions About the Power Tab Editor

Help Topics ● Introduction - Program overview and requirements ● What's New? - Program Version history; what was fixed and/or added in each version of the program ● Quick Steps To Creating A New Score - A simple guide to creating a Power Tab Score ● Getting Started ❍ Toolbars - Information on showing/hiding toolbars ❍ Creating A New Power Tab File - Information on how to create a new file ❍ The Score Layout - Describes how each Power Tab Score is laid out ❍ Navigating In Power Tab - Lists the different ways that you can traverse through a Power Tab score. ❍ The Status Bar - Description of what each pane signifies in the status bar. ● Sections and Staves ❍ What Is A Section? - Information on the core component used to construct Power Tab songs ❍ Adding A New Section - Information on how to add a new section to the score ❍ Attaching A Staff To A Section - Describes how attach a staff to a section so multiple guitar parts can be transcribed at the same time ❍ Changing The Number Of Tablature Lines On A Staff - Describes how to change the number of tablature staff lines on an existing staff ❍ Inserting A New Section - Describes how to insert a section within the score (as opposed to adding a section to the end of a score) ❍ Removing A Section Or Staff - Describes how to remove a section or staff from the score ❍ Position Width and Line Height - Describes how to change the width between positions and the distance between lines on the tablature staves ❍ Fills - Not implemented yet ● Song Properties ❍ File Information - How to edit the score -

51St International Congress on Medieval Studies

51st lntemational Congress on Medieval Studies May 12-15,2016 51st International Congress on Medieval Studies May 12–15, 2016 Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI 49008-5432 wmich.edu/medieval 2016 Table of Contents Welcome Letter iii Registration iv-v On-Campus Housing vi Off-Campus Accommodations vii Travel viii Driving and Parking ix Food x-xi Campus Shuttles xii Construction xiii Hotel Shuttles xiv Hotel Shuttle Schedules xv Facilities xvi Logistics xvii Varia xviii Lecture/Performance xix Exhibits Hall xx Exhibitors xxi Plenary Lectures xxii Advance Notice—2017 Congress xxiii The Congress: How It Works xxiv Travel Awards xxv Richard Rawlinson Center xxvi Center for Cistercian and Monastic Studies xxvii M.A. Program in Medieval Studies xxviii Medieval Institute Affiliated Faculty xxix Medieval Institute Publications xxx–xxxi About Western Michigan University xxxii Endowment and Gift Funds xxxiii The Otto Gründler Book Prize xxxiv 2016 Congress Schedule of Events 1–175 Index of Sponsoring Organizations 177–183 Index of Participants 185–205 List of Advertisers A-1 Advertising A-2 – A-48 Maps M-1 – M-7 ii The Medieval Institute College of Arts and Sciences Dear Colleague, Summer passed with the Call for Papers; fall came with a change of colors to Kalamazoo and the organization of sessions; we are now in winter here at Western Michigan University, starting to look forward to the spring and the arrival of you, our fellow medievalists, to the 51st International Congress on Medieval Studies. The Valley III cafeteria and adjoining rooms will host booksellers and vendors; cafeteria meals will be served in Valley II’s dining hall. -

Remembering Music in Early Greece

REMEMBERING MUSIC IN EARLY GREECE JOHN C. FRANKLIN This paper contemplates various ways that the ancient Greeks preserved information about their musical past. Emphasis is given to the earlier periods and the transition from oral/aural tradition, when self-reflective professional poetry was the primary means of remembering music, to literacy, when festival inscriptions and written poetry could first capture information in at least roughly datable contexts. But the continuing interplay of the oral/aural and written modes during the Archaic and Classical periods also had an impact on the historical record, which from ca. 400 onwards is represented by historiographical fragments. The sources, methods, and motives of these early treatises are also examined, with special attention to Hellanicus of Lesbos and Glaucus of Rhegion. The essay concludes with a few brief comments on Peripatetic historiography and a selective catalogue of music-historiographical titles from the fifth and fourth centuries. INTRODUCTION Greek authors often refer to earlier music.1 Sometimes these details are of first importance for the modern historiography of ancient 1 Editions and translations of classical authors may be found by consulting the article for each in The Oxford Classical Dictionary3. Journal 1 2 JOHN C. FRANKLIN Greek music. Uniquely valuable, for instance, is Herodotus’ allusion to an Argive musical efflorescence in the late sixth century,2 nowhere else explicitly attested (3.131–2). In other cases we learn less about real musical history than an author’s own biases and predilections. Thus Plato describes Egypt as a never-never- land where no innovation was ever permitted in music; it is hard to know whether Plato fabricated this statement out of nothing to support his conservative and ideal society, or is drawing, towards the same end, upon a more widely held impression—obviously superficial—of a foreign, distant culture (Laws 656e–657f). -

Conflict in the Peloponnese

CONFLICT IN THE PELOPONNESE Social, Military and Intellectual Proceedings of the 2nd CSPS PG and Early Career Conference, University of Nottingham 22-24 March 2013 edited by Vasiliki BROUMA Kendell HEYDON CSPS Online Publications 4 2018 Published by the Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies (CSPS), School of Humanities, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK. © Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies and individual authors ISBN 978-0-9576620-2-5 This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without express permission of the authors and the publisher of this volume. Furthermore, for any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/csps TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. i THE FAMILY AS THE INTERNAL ENEMY OF THE SPARTAN STATE ........................................ 1-23 Maciej Daszuta COMMEMORATING THE WAR DEAD IN ANCIENT SPARTA THE GYMNOPAIDIAI AND THE BATTLE OF HYSIAI .............................................................. 24-39 Elena Franchi PHILOTIMIA AND PHILONIKIA AT SPARTA ......................................................................... 40-69 Michele Lucchesi SLAVERY AS A POLITICAL PROBLEM DURING THE PELOPONESSIAN WARS ..................... 70-85 Bernat Montoya Rubio TYRTAEUS: THE SPARTAN POET FROM ATHENS SHIFTING IDENTITIES AS RHETORICAL STRATEGY IN LYCURGUS’ AGAINST LEOCRATES ................................................................................ 86-102 Eveline van Hilten-Rutten THE INFLUENCE OF THE KARNEIA ON WARFARE .......................................................... -

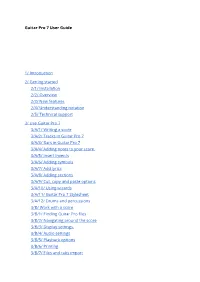

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting Started

Guitar Pro 7 User Guide 1/ Introduction 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/2/ Overview 2/3/ New features 2/4/ Understanding notation 2/5/ Technical support 3/ Use Guitar Pro 7 3/A/1/ Writing a score 3/A/2/ Tracks in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/3/ Bars in Guitar Pro 7 3/A/4/ Adding notes to your score. 3/A/5/ Insert invents 3/A/6/ Adding symbols 3/A/7/ Add lyrics 3/A/8/ Adding sections 3/A/9/ Cut, copy and paste options 3/A/10/ Using wizards 3/A/11/ Guitar Pro 7 Stylesheet 3/A/12/ Drums and percussions 3/B/ Work with a score 3/B/1/ Finding Guitar Pro files 3/B/2/ Navigating around the score 3/B/3/ Display settings. 3/B/4/ Audio settings 3/B/5/ Playback options 3/B/6/ Printing 3/B/7/ Files and tabs import 4/ Tools 4/1/ Chord diagrams 4/2/ Scales 4/3/ Virtual instruments 4/4/ Polyphonic tuner 4/5/ Metronome 4/6/ MIDI capture 4/7/ Line In 4/8 File protection 5/ mySongBook 1/ Introduction Welcome! You just purchased Guitar Pro 7, congratulations and welcome to the Guitar Pro family! Guitar Pro is back with its best version yet. Faster, stronger and modernised, Guitar Pro 7 offers you many new features. Whether you are a longtime Guitar Pro user or a new user you will find all the necessary information in this user guide to make the best out of Guitar Pro 7. 2/ Getting started 2/1/ Installation 2/1/1 MINIMUM SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS macOS X 10.10 / Windows 7 (32 or 64-Bit) Dual-core CPU with 4 GB RAM 2 GB of free HD space 960x720 display OS-compatible audio hardware DVD-ROM drive or internet connection required to download the software 2/1/2/ Installation on Windows Installation from the Guitar Pro website: You can easily download Guitar Pro 7 from our website via this link: https://www.guitar-pro.com/en/index.php?pg=download Once the trial version downloaded, upgrade it to the full version by entering your licence number into your activation window.