Glial Cells: the Other Cells of the Nervous System 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocabulario De Morfoloxía, Anatomía E Citoloxía Veterinaria

Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) Servizo de Normalización Lingüística Universidade de Santiago de Compostela COLECCIÓN VOCABULARIOS TEMÁTICOS N.º 4 SERVIZO DE NORMALIZACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Vocabulario de Morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria (galego-español-inglés) 2008 UNIVERSIDADE DE SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA VOCABULARIO de morfoloxía, anatomía e citoloxía veterinaria : (galego-español- inglés) / coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río, Servizo de Normalización Lingüística ; autores Matilde Lombardero Fernández ... [et al.]. – Santiago de Compostela : Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, 2008. – 369 p. ; 21 cm. – (Vocabularios temáticos ; 4). - D.L. C 2458-2008. – ISBN 978-84-9887-018-3 1.Medicina �������������������������������������������������������������������������veterinaria-Diccionarios�������������������������������������������������. 2.Galego (Lingua)-Glosarios, vocabularios, etc. políglotas. I.Lombardero Fernández, Matilde. II.Rodríguez Rio, Xusto A. coord. III. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística, coord. IV.Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, ed. V.Serie. 591.4(038)=699=60=20 Coordinador Xusto A. Rodríguez Río (Área de Terminoloxía. Servizo de Normalización Lingüística. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela) Autoras/res Matilde Lombardero Fernández (doutora en Veterinaria e profesora do Departamento de Anatomía e Produción Animal. -

Schwann Cells (Cell Culture/Laminin) SETH PORTER*T, Luis GLASER*T, and RICHARD P

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 84, pp. 7768-7772, November 1987 Neurobiology Release of autocrine growth factor by primary and immortalized Schwann cells (cell culture/laminin) SETH PORTER*t, Luis GLASER*t, AND RICHARD P. BUNGEt Departments of *Biological Chemistry and tAnatomy and Neurobiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110; and tDepartments of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL 33156 Communicated by Gerald D. Fischbach, July 20, 1987 ABSTRACT Schwann cells derived from neonatal rat proliferation. Because Schwann cells secrete laminin and sciatic nerve are quiescent in culture unless treated with specific form a basement membrane at an initial stage of neuronal mitogens. The use of glial growth factor (GGF) and forskolin ensheathment (21), it is important to establish the role of has been found to be an effective method for stimulating these components in the control of proliferation and differ- proliferation of Schwann cells on a poly(L-lysine) substratum entiation. while maintaining their ability to myelinate axons in vitro. We We report that repetitive passaging of Schwann cells find that repetitive passaging of Schwann cells with GGF and derived from neonatal rat can result in a population of forskolin results in the loss of normal growth control; the cells immortalized cells that, depending upon their duration in are able to proliferate without added mitogens. The immor- culture, display all or most ofthe functional characteristics of talized cells grow continuously in the absence of added growth a primary Schwann cell. It was found that both immortalized factor and in the presence or absence of serum yet continue to and primary Schwann cells secrete growth-promoting activ- express distinctive Schwann cell-surface antigens. -

A System for Studying Mechanisms of Neuromuscular Junction Development and Maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 2464-2477 doi:10.1242/dev.130278 TECHNIQUES AND RESOURCES RESEARCH ARTICLE A system for studying mechanisms of neuromuscular junction development and maintenance Valérie Vilmont1,‡, Bruno Cadot1, Gilles Ouanounou2 and Edgar R. Gomes1,3,*,‡ ABSTRACT different animal models and cell lines (Chen et al., 2014; Corti et al., The neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a cellular synapse between a 2012; Lenzi et al., 2015) with the hope of recapitulating some motor neuron and a skeletal muscle fiber, enables the translation of features of neuromuscular diseases and understanding the triggers chemical cues into physical activity. The development of this special of one of their common hallmarks: the disruption of the structure has been subject to numerous investigations, but its neuromuscular junction (NMJ). The NMJ is one of the most complexity renders in vivo studies particularly difficult to perform. studied synapses. It is formed of three key elements: the lower motor In vitro modeling of the neuromuscular junction represents a powerful neuron (the pre-synaptic compartment), the skeletal muscle (the tool to delineate fully the fine tuning of events that lead to subcellular post-synaptic compartment) and the Schwann cell (Sanes and specialization at the pre-synaptic and post-synaptic sites. Here, we Lichtman, 1999). The NMJ is formed in a step-wise manner describe a novel heterologous co-culture in vitro method using rat following a series of cues involving these three cellular components spinal cord explants with dorsal root ganglia and murine primary and its role is basically to ensure the skeletal muscle functionality. -

The Histology of the Neuromuscular Junction In

75 THE HISTOLOGY OF THE NEUROMUSCULAR JUNCTION Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/brain/article/84/1/75/372729 by guest on 27 September 2021 IN DYSTROPHIA MYOTONICA BY VIOLET MACDERMOT Department of Neurology, St. Thomas' Hospital, London, S.E.I (1) INTRODUCTION DYSTROPJHC MYOTONICA is a familial disease affecting males and females, usually presenting in adult life, characterized by muscular wasting and weakness together with certain other features. The muscles mainly in- volved are the temporal, masseter, facial, sternomastoid and limb muscles, in the latter those mainly affected being peripheral in distribution. A widespread disorder of muscular contraction, myotonia, is also present but is noticed chiefly in the tongue and in the muscles involved in grasping. The other features of the condition are some degree of mental defect, dysphonia, cataracts, frontal baldness, sparse body hair and testicular atrophy. Any of the manifestations of the disease may be absent and the order of presentation of symptoms is variable. The myotonia may precede muscular wasting by many years or may occur independently. In those muscles which are severely wasted the myotonia tends to disappear. The interest of dystrophia myotonica lies in the peculiar distribution of muscle involvement and in the combination of a disorder of muscle function with endocrine and other dysplasic features. The results of histological examination of biopsy and post-mortem material have been described and reviewed by numerous workers, notably Steinert (1909), Adie and Greenfield (1923), Keschner and Davison (1933), Hassin and Kesert (1948), Wohlfart (1951), Adams, Denny-Brown and Pearson (1953), Greenfield, Shy, Alvord and Berg (1957). -

Clustering of Na+ Channels and Node of Ranvier Formation in Remyelinating Axons

The Journal of Neuroscience, January 1995, 15(l): 492503 Clustering of Na+ Channels and Node of Ranvier Formation in Remyelinating Axons Sanja Dugandgija-NovakoviC,’ Adam G. Koszowski,2 S. Rock Levinson,2 and Peter Shragerl ‘Department of Physiology, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York 14642 and 2Department of Physiology, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Denver, Colorado 80262 Polyclonal antibodies were raised against a well conserved nodal regions(Black et al., 1990). The density of Na+ channels, region of the vertebrate Na+ channel and were affinity pu- in particular, is about 25 times higher at nodesof Ranvier than rified for use in immunocytochemistry. Focal demyelination at internodal sites (Shrager, 1989). There has been vigorous of rat sciatic axons was initiated by an intraneural injection debate over the mechanism of Na+ channel clustering during of lysolecithin and Na+ channel clustering was followed at myelination, particularly with respect to the role of Schwann several stages of myelin removal and repair. At 1 week post- cells, and studies have included both developing nerve and injection axons contained long, fully demyelinated regions. pathological conditions (Ellisman, 1979; Rosenbluth, 1979; Ro- Na+ channel clusters appeared only at heminodes forming senbluth and Blakemore, 1984; Le Beau et al., 1987; England the borders of these zones, and at widely spaced isolated et al., 1990, 1991; Joe and Angelides, 1992, 1993).There remain sites that may represent former nodes of Ranvier. Over the many interesting questions, particularly regarding remodeling next few days proliferating Schwann cells adhered to axons that occurs following myelin disruption. When axons are de- and began to extend processes. -

Schwann Cell Processes Guide Regeneration of Peripheral Axons

Neuron, Vol. 14, 125-132, January, 1995, Copyright © 1995 by Cell Press Schwann Cell Processes Guide Regeneration of Peripheral Axons Young-Jin Son and Wesley J. Thompson come immunoreactive (Astrow et al., 1994). There is a Center for Developmental Biology similar up-regulation of immunoreactivity in Schwann cells and Department of Zoology of the nerve following axonal degeneration. University of Texas Motor axons commonly reinnervate muscle fibers by Austin, Texas 78712 growing down the old endoneurial Schwann cell tubes leading to each endplate. Some axons continue to grow beyond their endplates (Tello, 1907; Ramon y Cajal, 1928; Summary Gutmann and Young, 1944; Letinsky et al., 1976; Gorio et al., 1983), forming so-called "escaped" fibers. In some Terminal Schwann cells overlying the neuromuscular cases these escaped fibers grow to reinnervate nearby junction sprout elaborate processes upon muscle de- endplates. Muscle fibers reinnervated by an escaped fiber nervation. We show here that motor axons use these from an adjacent endplate as well as by an axon regenerat- processes as guides/substrates during regeneration; ing down the old Schwann cell tube become polyneuro- in so doing, they escape the confines of endplates and nally innervated (Rich and Lichtman, 1989). We wondered grow between endplates to generate polyneuronal in- whether the processes extended by terminal Schwann nervation. We also show that Schwann cells in the cells play a role in the generation of escaped fibers and nerve provide similar guidance. Axons extend from the polyneuronal reinnervation. Using immunocytochemistry, cut end of a nerve in association with Schwann cell we found that motor axons use processes of terminal processes and appear to navigate along them. -

Glial Cells Are Involved in Itch Processing

Acta Derm Venereol 2016; 96: 723–727 REVIEW ARTICLE Glial Cells are Involved in Itch Processing Hjalte H. ANDERSEN, Lars ARENDT-NIELSEN and Parisa GAZERANI SMI®, Department of Health Science and Technology, School of Medicine, Aalborg University, Denmark Recent discoveries in itch neurophysiology include itch- worsening the skin lesions and leading to more or pro- selective neuronal pathways, the clinically relevant non- longed pruritus (5, 6). This phenomenon, known as the histaminergic pathway, and elucidation of the notable itch–scratch–itch vicious cycle, is physiologically com- similarities and differences between itch and pain. Po- plex and is likely to involve: local inflammatory medi- tential involvement of glial cells in itch processing and ators and structural changes, reward components, and the possibility of glial modulation of chronic itch have the autonomic nervous system (5, 7). In most conditions recently been identified, similarly to the established glial associated with chronic itch, very limited or ambiguous modulation of pain processing. This review outlines the evidence is found for the effectiveness of pharmaceutical similarities and differences between itch and pain, and interventions, and the evidence is often characterized by how different types of central and peripheral glial cells off-label small-scale trials or case series. Histamine is may be differentially involved in the development of ch- now widely accepted not to have a key role in evoking ronic itch akin to their more investigated role in chronic itch in most of the clinical conditions characterized by pain. Improvements are needed in the management of chronic pruritus (for an overview of itch neurobiology chronic itch, and future basic and interventional studies and mechanisms, see recent reviews in the field [8, 9]). -

Regulation of Myelin Structure and Conduction Velocity by Perinodal Astrocytes

Correction NEUROSCIENCE Correction for “Regulation of myelin structure and conduc- tion velocity by perinodal astrocytes,” by Dipankar J. Dutta, Dong Ho Woo, Philip R. Lee, Sinisa Pajevic, Olena Bukalo, William C. Huffman, Hiroaki Wake, Peter J. Basser, Shahriar SheikhBahaei, Vanja Lazarevic, Jeffrey C. Smith, and R. Douglas Fields, which was first published October 29, 2018; 10.1073/ pnas.1811013115 (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115,11832–11837). The authors note that the following statement should be added to the Acknowledgments: “We acknowledge Dr. Hae Ung Lee for preliminary experiments that informed the ultimate experimental approach.” Published under the PNAS license. Published online June 10, 2019. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1908361116 12574 | PNAS | June 18, 2019 | vol. 116 | no. 25 www.pnas.org Downloaded by guest on October 2, 2021 Regulation of myelin structure and conduction velocity by perinodal astrocytes Dipankar J. Duttaa,b, Dong Ho Wooa, Philip R. Leea, Sinisa Pajevicc, Olena Bukaloa, William C. Huffmana, Hiroaki Wakea, Peter J. Basserd, Shahriar SheikhBahaeie, Vanja Lazarevicf, Jeffrey C. Smithe, and R. Douglas Fieldsa,1 aSection on Nervous System Development and Plasticity, The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; bThe Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817; cMathematical and Statistical Computing Laboratory, Office of Intramural Research, Center for Information -

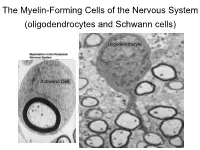

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (Oligodendrocytes and Schwann Cells)

The Myelin-Forming Cells of the Nervous System (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) Oligodendrocyte Schwann Cell Oligodendrocyte function Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Oligodendroglia PMD PMD Saltatory (jumping) nerve conduction Investigating the Myelinogenic Potential of Individual Oligodendrocytes In Vivo Sparse Labeling of Oligodendrocytes CNPase-GFP Variegated expression under the MBP-enhancer Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Corpus Callosum Cerebral Cortex Caudate Putamen Piriform Cortex Corpus Callosum Ant Commissure Characterization of Oligodendrocyte Morphology Cerebral Cortex Corpus Callosum Caudate Putamen Cerebellum Brain Stem Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes in disease: Cerebral Palsy ! CP major cause of chronic neurological morbidity and mortality in children ! CP incidence now about 3/1000 live births compared to 1/1000 in 1980 when we started intervening for ELBW ! Of all ELBW {gestation 6 mo, Wt. 0.5kg} , 10-15% develop CP ! Prematurely born children prone to white matter injury {WMI}, principle reason for the increase in incidence of CP ! ! 12 Cerebral Palsy Spectrum of white matter injury ! ! Macro Cystic Micro Cystic Gliotic Khwaja and Volpe 2009 13 Rationale for Repair/Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis Oligodendrocyte specification oligodendrocytes specified from the pMN after MNs - a ventral source of oligodendrocytes -

1365.Full.Pdf

The Journal of Neuroscience May 1966, 6(5): 1365-1371 Analysis of the Carbohydrate Composition of Axonally Transported Glycoconjugates in Sciatic Nerve Clyde E. Hart and John G. Wood Department of Anatomy, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia 30322 Glycosidase enzyme digestion in combination with postembed- schlag and Stone, 1982, for reviews). Therefore, the ability to ding lectin cytochemistry was used to study the carbohydrate characterize in situ the carbohydrate compositionof lectin bind- composition of axonally transported glycoproteins. A cold block ing sites of intracellular membranecompartments and on the procedure for the interruption of axonal transport was employed cell surface may further our understandingof the site(s) of gly- to increase selectively the population of anterograde moving coprotein oligosaccharideprocessing in neurons. components on the proximal side of the transport block. Elec- tron-microscopic observations revealed that a cold block applied In this study we have used a modification of the cold block to the sciatic nerve of an anesthetized rat produced an increase technique of Hanson (1978) to interrupt axonal transport in the in axonal smooth membrane vesicles at a site directly proximal sciatic nerve of rats in order to increase the content of antero- to the cold block. Postembedding lectin cytochemistry of the gradely transported glycoproteins at a focal point along the nerve. sciatic nerve demonstrated a substantial increase in concanav- Results of postembedding lectin cytochemistry and endo- and alin A (Con A), wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), and succinylat- exo-glycosidase digestions of the cold-blocked sciatic nerve in- ed WGA binding sites in axons directly proximal to the cold dicated that some of the axonally transported glycoprotein car- block. -

Nomina Histologica Veterinaria, First Edition

NOMINA HISTOLOGICA VETERINARIA Submitted by the International Committee on Veterinary Histological Nomenclature (ICVHN) to the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists Published on the website of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists www.wava-amav.org 2017 CONTENTS Introduction i Principles of term construction in N.H.V. iii Cytologia – Cytology 1 Textus epithelialis – Epithelial tissue 10 Textus connectivus – Connective tissue 13 Sanguis et Lympha – Blood and Lymph 17 Textus muscularis – Muscle tissue 19 Textus nervosus – Nerve tissue 20 Splanchnologia – Viscera 23 Systema digestorium – Digestive system 24 Systema respiratorium – Respiratory system 32 Systema urinarium – Urinary system 35 Organa genitalia masculina – Male genital system 38 Organa genitalia feminina – Female genital system 42 Systema endocrinum – Endocrine system 45 Systema cardiovasculare et lymphaticum [Angiologia] – Cardiovascular and lymphatic system 47 Systema nervosum – Nervous system 52 Receptores sensorii et Organa sensuum – Sensory receptors and Sense organs 58 Integumentum – Integument 64 INTRODUCTION The preparations leading to the publication of the present first edition of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria has a long history spanning more than 50 years. Under the auspices of the World Association of Veterinary Anatomists (W.A.V.A.), the International Committee on Veterinary Anatomical Nomenclature (I.C.V.A.N.) appointed in Giessen, 1965, a Subcommittee on Histology and Embryology which started a working relation with the Subcommittee on Histology of the former International Anatomical Nomenclature Committee. In Mexico City, 1971, this Subcommittee presented a document entitled Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft as a basis for the continued work of the newly-appointed Subcommittee on Histological Nomenclature. This resulted in the editing of the Nomina Histologica Veterinaria: A Working Draft II (Toulouse, 1974), followed by preparations for publication of a Nomina Histologica Veterinaria. -

Specific Labeling of Synaptic Schwann Cells Reveals Unique Cellular And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Specific labeling of synaptic schwann cells reveals unique cellular and molecular features Ryan Castro1,2,3, Thomas Taetzsch1,2, Sydney K Vaughan1,2, Kerilyn Godbe4, John Chappell4, Robert E Settlage5, Gregorio Valdez1,2,6* 1Department of Molecular Biology, Cellular Biology, and Biochemistry, Brown University, Providence, United States; 2Center for Translational Neuroscience, Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science and Brown Institute for Translational Science, Brown University, Providence, United States; 3Neuroscience Graduate Program, Brown University, Providence, United States; 4Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech Carilion, Roanoke, United States; 5Department of Advanced Research Computing, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, United States; 6Department of Neurology, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, United States Abstract Perisynaptic Schwann cells (PSCs) are specialized, non-myelinating, synaptic glia of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), that participate in synapse development, function, maintenance, and repair. The study of PSCs has relied on an anatomy-based approach, as the identities of cell-specific PSC molecular markers have remained elusive. This limited approach has precluded our ability to isolate and genetically manipulate PSCs in a cell specific manner. We have identified neuron-glia antigen 2 (NG2) as a unique molecular marker of S100b+ PSCs in skeletal muscle. NG2 is expressed in Schwann cells already associated with the NMJ, indicating that it is a marker of differentiated PSCs. Using a newly generated transgenic mouse in which PSCs are specifically labeled, we show that PSCs have a unique molecular signature that includes genes known to play critical roles in *For correspondence: PSCs and synapses. These findings will serve as a springboard for revealing drivers of PSC [email protected] differentiation and function.