Draft Recommendations for Use of Smallpox Vaccine in a Pre-Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painful Bubbles

Osteopathic Family Physician (2018) 29 - 31 29 CLINICAL IMAGES Painful Bubbles Craig Bober, DO & Amy Schultz, DO Lankenau Hospital Family Medicine Residency A 25 year-old female with a past medical history of well controlled eczema presented to her primary care physician with a one week his- tory of a painful “bubbles” localized to her right antecubital fossa as seen in Figure 1. She noted that the new rash appeared to form over- night, was extremely painful, and would occasionally drain a clear liquid after scratching. It did not respond to her usual over-the-counter regimen of moisturizers prompting her to be evaluated. She had subjective fevers and malaise but denied oral or genital ulcers, vaginal discharge, dysuria, ocular irritation, visual disturbances, and upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. Review of systems was oth- erwise unremarkable. She had no other known medical problems, allergies, and denied drug and alcohol use. She denied any recent travel, sick contacts, pets, or OTC medications/creams. She was sexually active in a monogamous relationship for over a year. QUESTIONS 1. What is the most likely diagnosis? A. Cellulitis B. Eczema herpeticum C. Impetigo D. Primary varicella infection 2. Which test should be performed initally? A. Blood culture B. Direct fuorescent antibody staining FIGURE 1: C. Tzanck smear D. Wound culture 3. What is the best treatment? A. Acyclovir B. Augmentin C. Doxycycline D. Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin CORRESPONDENCE: Amy Schultz, DO | [email protected] 1877-5773X/$ - see front matter. © 2018 ACOFP. All rights reserved. 30 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 10, No. 3 | May/June, 2018 ANSWERS 1. -

Eczema Vaccinatum in Indiana’S Public Health Nurses Play a Vital Role in Protecting, Aiding, Child Resulting from and Educating Hoosiers

Volume 10, Issue 6 June 2007 Public Health Nurse Conference Article Page 2007 No. Public Health Nurse Tom Duszynski, BS Conference 2007 1 Eczema Vaccinatum in Indiana’s public health nurses play a vital role in protecting, aiding, Child Resulting from and educating Hoosiers. The Indiana State Department of Health Transmission of (ISDH) recognizes the contribution these nurses make to public health Vaccinia from in Indiana and assists their efforts by offering continuing education Smallpox Vaccinee opportunities, such as the annual Public Health Nurse Conference. with Tertiary Spread to the Mother 3 On June 8, more than 150 public A Decade of Indiana health nurses and Sentinel Influenza Data nursing students Surveillance 8 attended the 2007 ISDH Public Training Room 13 Health Nurse Conference. This Data Reports 14 year’s conference was the most well HIV Summary 14 attended in conference history. Disease Reports 15 Several years ago, the conference began as a “training day” to provide newly hired public health nurses with general education about public health responsibilities within local health departments. The conference has consistently grown over the past several years, and new ideas and different topics have emerged based on suggestions from those who have attended. Conference planners have used participants’ input to restructure the program to meet the needs of public health nurses. This year’s conference was no exception. Deputy State Health Commissioner Mary Hill, an attorney and registered nurse, opened the conference by reminding public health nurses and nursing students of the important work they do every day for Hoosiers and how, since September 11, 2001, their roles and knowledge have changed and expanded to include the world of preparedness, again demonstrating the flexibility of public health nursing. -

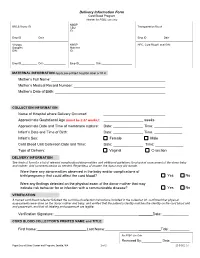

Delivery Information Form Cord Blood Program Header for PSBC Use Only NMDP BBCS Donor ID______CBU Transportation Box #______ID

Delivery Information Form Cord Blood Program Header for PSBC use only NMDP BBCS Donor ID________________________ CBU Transportation Box #____________________ ID: Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Virology NMDP HPC, Cord Blood Local DIN: Samples Maternal DIN: ID: Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Emp ID___________ Date_____________________ MATERNAL INFORMATION Apply pre-printed hospital label or fill in Mother’s Full Name: Mother’s Medical Record Number: Mother’s Date of Birth: COLLECTION INFORMATION Name of Hospital where Delivery Occurred: Approximate Gestational Age (must be ≥ 37 weeks): _ weeks Approximate Date and Time of membrane rupture: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Infant’s Date and Time of Birth: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Infant’s Sex: Female Male Cord Blood Unit Collection Date and Time: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Type of Delivery: Vaginal C-section DELIVERY INFORMATION See back of form for a list of relevant complications/abnormalities and additional guidelines for physical assessment of the donor baby and mother. Add comments below as needed. Regardless of answer, the donor may still donate. Were there any abnormalities observed in the baby and/or complications of birth/pregnancy that could affect the cord blood? Yes No Were any findings detected on the physical exam of the donor mother that may indicate risk behavior for or infection with a communicable disease? Yes No VERIFICATION A trained cord blood collector followed the cord blood collection instructions included in the collection kit, confirmed that physical assessments were done on the donor mother and baby, and verified that the patient’s identity matches the identity on the cord blood unit and paperwork, and that all labeling and paperwork are legible. -

Disseminated Varicella Zoster Virus Infection After Vaccination with a Live Attenuated Vaccine

PRACTICE | CASES SEPSIS CPD Disseminated varicella zoster virus infection after vaccination with a live attenuated vaccine Vinita Dubey MD, Derek MacFadden MD n Cite as: CMAJ 2019 September 16;191:E1025-7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.190270 70-year-old man presented to the emergency depart- ment with a 2-week history of rash, which started as a KEY POINTS localized eruption on his forehead and progressed to a • Live attenuated vaccines are capable of causing symptomatic vesicularA rash involving his entire body (Figure 1). Over this same vaccine-derived infection, even weeks following vaccination. period, he noted increasing shortness of breath, tiredness, pain- • Immunocompromised hosts, including those taking low-dose ful swallowing and chills. He did not report recent travel. immunosuppressive medications, are at increased risk for The patient had a past history of hypertension, coronary artery infection with live vaccine strains. disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary • Caution is required before using live attenuated vaccines in immunocompromised people; expert consultation may be disease and atrial flutter. Successful cardiac ablation had been required. performed 2 weeks before the onset of the rash. He also had rheu- • Severe and unusual adverse events following vaccination matoid arthritis, treated with methotrexate, 2.5 mg/d (6 d per should be reported to local public health authorities for week) for 3 years, hydroxychloroquine, 200 mg/d and prednisone, surveillance and investigative purposes. 10 mg/d. In the previous month, his prednisone dosage had been tapered from 10 mg/d. He was not receiving any biologic agents. On examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 110/60 mm Hg, multiple vesicular and crusted lesions, disseminated varicella heart rate 86 beats/min and temperature 36.8°C. -

Skin Conditions That Mean You Should Not Get Smallpox Vaccine

SMALLPOX VACCINE INFORMATION STATEMENT (VIS) SUPPLEMENT C Skin Conditions That Mean You Should Not Get Smallpox Vaccine The smallpox vaccine is made from a live virus related to smallpox called vaccinia (not smallpox virus). The vaccine stimulates the immune system to react against the vaccinia virus, and develop immunity to it. Immunity to vaccinia also provides immunity to smallpox. For most people, live virus vaccines are safe and effective. However, people with certain skin conditions are more likely to have rare and serious reactions to the smallpox vaccine, including bad skin rashes (eczema vaccinatum).This results when virus from the vaccine site gets into broken skin and causes a rash in that area. While most people recover from this rash with treatment, it can be quite severe, sometimes leading to scarring or even death. SKIN CONDITIONS THAT MEAN YOU SHOULD NOT BE VACCINATED: • Individuals who have ever been diagnosed with eczema or atopic dermatitis, (conditions involving repeated episodes of red, itchy or inflamed skin) even if the condition is mild, not presently active, or if you had it only as a child, should not get the vaccine. • Individuals with Darier’s disease should not get the vaccine. • Individuals in close contact with someone who has ever been diagnosed with eczema or atopic dermatitis, even if the condition is mild, not presently active, or if they had it only as a child, should not get the vaccine because of the risk it poses to that close contact. (Close contacts include anyone living in your household and anyone you have close physical contact with such as a sexual partner.) SKIN CONDITIONS THAT MEAN YOU SHOULD WAIT BEFORE BEING VACCINATED: • Individuals with breaks in their skin should not be vaccinated until the skin is fully healed. -

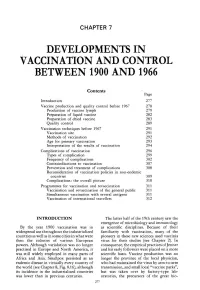

Chapter 7. Developments in Vaccination and Control Between

CHAPTER 7 DEVELOPMENTS IN VACCINATION AND CONTROL BETWEEN 1900 AND 1966 Contents Page Introduction 277 Vaccine production and quality control before 1967 278 Production of vaccine lymph 279 Preparation of liquid vaccine 282 Preparation of dried vaccine 283 Quality control 289 Vaccination techniques before 1967 291 Vaccination site 291 Methods of vaccination 292 Age for primary vaccination 293 Interpretation of the results of vaccination 294 Complications of vaccination 296 Types of complication 299 Frequency of complications 302 Contraindications to vaccination 307 Prevention and treatment of complications 308 Reconsideration of vaccination policies in non-endemic countries 309 Complications : the overall picture 310 Programmes for vaccination and revaccination 311 Vaccination and revaccination of the general public 311 Simultaneous vaccination with several antigens 311 Vaccination of international travellers 312 INTRODUCTION The latter half of the 19th century saw the emergence of microbiology and immunology By the year 1900 vaccination was in as scientific disciplines . Because of their widespread use throughout the industrialized familiarity with vaccination, many of the countries as well as in some cities in what were pioneers in these new sciences used vaccinia then the colonies of various European virus for their studies (see Chapter 2) . In powers . Although variolation was no longer consequence, the empirical practices of Jenner practised in Europe and North America, it and his early followers were placed on a more was still widely employed in many parts of scientific basis . Vaccine production was no Africa and Asia . Smallpox persisted as an longer the province of the local physician, endemic disease in virtually every country of who had maintained the virus by arm-to-arm the world (see Chapter 8, Fig. -

Therapeutic Vaccines and Antibodies for Treatment of Orthopoxvirus Infections

Viruses 2010, 2, 2381-2403; doi:10.3390/v2102381 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Review Therapeutic Vaccines and Antibodies for Treatment of Orthopoxvirus Infections Yuhong Xiao 1 and Stuart N. Isaacs 1,2,* 1 Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Pennsylvania, School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Infectious Diseases Section, Philadelphia Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-215-662-2150; Fax: +1-215-349-5111. Received: 19 September 2010; in revised form: 9 October 2010 / Accepted: 13 October 2010 / Published: 20 October 2010 Abstract: Despite the eradication of smallpox several decades ago, variola and monkeypox viruses still have the potential to become significant threats to public health. The current licensed live vaccinia virus-based smallpox vaccine is extremely effective as a prophylactic vaccine to prevent orthopoxvirus infections, but because of safety issues, it is no longer given as a routine vaccine to the general population. In the event of serious human orthopoxvirus infections, it is important to have treatments available for individual patients as well as their close contacts. The smallpox vaccine and vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) were used in the past as therapeutics for patients exposed to smallpox. VIG was also used in patients who were at high risk of developing complications from smallpox vaccination. Thus post-exposure vaccination and VIG treatments may again become important therapeutic modalities. This paper summarizes some of the historic use of the smallpox vaccine and immunoglobulins in the post-exposure setting in humans and reviews in detail the newer animal studies that address the use of therapeutic vaccines and immunoglobulins in orthopoxvirus infections as well as the development of new therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. -

Kaposi's Varicelliform Eruption

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Kaposi’s Varicelliform Eruption: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Sasha C. Kramer, MD; Chadwick J. Thomas, MD; William B. Tyler, MD; Dirk M. Elston, MD GOAL To gain a thorough understanding of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Recognize Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption. 2. Distinguish herpetic from vaccine-associated forms of Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption. 3. Manage Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in affected patients. CME Test on page 123. This article has been peer reviewed and is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing approved by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of medical education for physicians. Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates Review date: January 2004. this educational activity for a maximum of 1 This activity has been planned and implemented category 1 credit toward the AMA Physician’s in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies Recognition Award. Each physician should claim of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical only that hour of credit that he/she actually spent Education through the joint sponsorship of Albert in the activity. Einstein College of Medicine and Quadrant This activity has been planned and produced in HealthCom, Inc. Albert Einstein College of Medicine accordance with ACCME Essentials. Drs. Kramer, Thomas, Tyler, and Elston report no conflict of interest. The authors report discussion of off-label use for intravenous vaccinia immune globulin under an investigational new drug protocol. Dr. Fisher reports no conflict of interest. Disseminated herpes or vaccinia in the setting of eczema herpeticum in a woman with a long- underlying skin diseases is known as Kaposi’s standing history of atopic dermatitis (AD). -

Vaccines Could Halt Third World Health Crisis Vaccines by Anita Manning 2 Human Beings Are Born with the Bare Minimum of Defenses Against Infectious Diseases

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER PTK2003-04 Collegiate Case Study www.usatodaycollege.com Vaccines could halt Third World health crisis Vaccines By Anita Manning 2 Human beings are born with the bare minimum of defenses against infectious diseases. It is the job of a healthy immune system to strengthen itself over Vaccine use spreading time by recognizing and adapting to new threats. When a new, potentially harmful microbe enters the body, the immune system provides defense By Gary Mihoces 2 against it in the form of antibodies. More importantly, the body will remember the attacker and remember how to kill it. This secondary response provides immunity from future infection. Vaccines increase our protection by stimulating the immune system to generate antibodies against specific antigens. Large-scale vaccination of the population, called herd immunity, also provides an important defense against infectious disease. Herd immunity limits outbreaks because there are not enough susceptible people to support an epidemic. Well before the development of vaccines, humans knew that prior infection to a disease could protect a person from getting that disease again. Recorded history provides many examples of vaccination techniques being used without a full understanding of the mechanisms that allow them to work. As early as the 10th century, Chinese physicians had children inhale dried and powdered smallpox scabs. In 18th Century England, a similar procedure was used when Photo by Tim Dillon, USA TODAY small pox scabs were scratched into children's skin. Unfortunately, in some cases the procedure did backfire and kill the recipient. However, the 1% Cancer vaccine shows mortality rate was a vast improvement over the 50% mortality of smallpox. -

Atopic Dermatitis: a Practice Parameter Update 2012

Practice parameter Atopic dermatitis: A practice parameter update 2012 Authors: Lynda Schneider, MD, Stephen Tilles, MD, Peter Lio, MD, Mark Boguniewicz, MD, Lisa Beck, MD, Jennifer LeBovidge, PhD, and Natalija Novak, MD Joint Task Force Contributors: David Bernstein, MD, Joann Blessing-Moore, MD, David Khan, MD, David Lang, MD, Richard Nicklas, MD, John Oppenheimer, MD, Jay Portnoy, MD, Christopher Randolph, MD, Diane Schuller, MD, Sheldon Spector, MD, Stephen Tilles, MD, and Dana Wallace, MD This parameter was developed by the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters for Allergy & Immunology are available Practice Parameters, representing the American Academy of online at http://www.jcaai.org. (J Allergy Clin Immunol Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI); the American 2013;131:295-9.) College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI); and the Key words: Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The AAAAI Atopic dermatitis/atopic eczema, pathogenesis, genet- and the ACAAI have jointly accepted responsibility for ics, diagnosis, management, therapy, triggers, Staphylococcus, qual- establishing ‘‘Atopic dermatitis: a practice parameter update ity of life, sleep, cyclosporine, immunomodulating agents, 2012.’’ This is a complete and comprehensive document at phototherapy, allergen immunotherapy the current time. The medical environment is a changing environment, and not all recommendations will be appropriate To read the Practice Parameter in its entirety, please download for all patients. Because this document incorporated the the online version of this article from www.jacionline.org. Please efforts of many participants, no single individual, including note that all references cited in this print version can be found in those who served on the Joint Task Force, is authorized to the full online document. -

Vaccinations in Pregnancy DENISE K

Vaccinations in Pregnancy DENISE K. SUR, M.D., and DAVID H.WALLIS, M.D., David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California—Los Angeles, California THEODORE X. O’CONNELL, M.D., Kaiser Permanente–Woodland Hills, Woodland Hills, California Adult immunization rates have fallen short of national goals partly because of mis- conceptions about the safety and benefits of current vaccines. The danger of these misconceptions is magnified during pregnancy, when concerned physicians are hesi- tant to administer vaccines and patients are reluctant to accept them. Routine vaccines that generally are safe to administer during pregnancy include diphtheria, tetanus, influenza, and hepatitis B. Other vaccines, such as meningococcal and rabies, may be considered. Vaccines that are contraindicated, because of the theoretic risk of fetal transmission, include measles, mumps, and rubella; varicella; and bacille Calmette- Guérin. A number of other vaccines have not yet been adequately studied; therefore, theoretic risks of vaccination must be weighed against the risks of the disease to mother and fetus. Inadvertent administration of any of these vaccinations, however, is not considered an indication for termination of the pregnancy. (Am Fam Physician 2003;68:E299-309. Copyright© 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians.) This article he administration of vaccines Vaccines commonly administered by family exemplifies the AAFP during pregnancy poses a num- physicians, and their indication for use during 2003 Annual Clinical ber of concerns to physicians and pregnancy, are summarized in Table 1.1 Focus on prevention and health promotion. patients about the risk of trans- Women of childbearing age often are con- mitting a virus to a developing cerned about whether breastfeeding is safe Tfetus. -

Purpuric Skin Rash in a Patient Undergoing Pfizer

Communication Purpuric Skin Rash in a Patient Undergoing Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccination: Histological Evaluation and Perspectives Gerardo Cazzato 1,* , Paolo Romita 2, Caterina Foti 1, Antonietta Cimmino 1, Anna Colagrande 1, Francesca Arezzo 3, Sara Sablone 4 , Angela Barile 1, Teresa Lettini 1 , Leonardo Resta 1 and Giuseppe Ingravallo 1 1 Section of Pathology, Departmente of Emergency and Organ Transplantation (DETO), University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (C.F.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (T.L.); [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (G.I.) 2 Department of Biomedical Science and Human Oncology, Dermatological Clinic, University of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology, Gynecologic and Obstetrics Clinic, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 4 Section of Legal Medicine, Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, Policlinico di Bari Hospital, University of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the entire planet, and within about a year and a half, Citation: Cazzato, G.; Romita, P.; has led to 174,502,686 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide, with 3,770,361 deaths. Although it Foti, C.; Cimmino, A.; Colagrande, A.; is now clear that SARS-CoV-2 can affect various different organs, including the lungs, brain, skin, Arezzo, F.; Sablone, S.; Barile, A.; vessels, placenta and others, less is yet known about adverse reactions from vaccines, although more Lettini, T.; Resta, L.; et al.