Kaposi's Varicelliform Eruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poxviruses: Smallpox Vaccine, Its Complications and Chemotherapy

Virus Adaptation and Treatment Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article R E V IEW Poxviruses: smallpox vaccine, its complications and chemotherapy Mimi Remichkova Abstract: The threat of bioterrorism in the recent years has once again posed to mankind the unresolved problems of contagious diseases, well forgotten in the past. Smallpox (variola) is Department of Pathogenic Bacteria, The Stephan Angeloff Institute among the most dangerous and highly contagious viral infections affecting humans. The last of Microbiology, Bulgarian Academy natural case in Somalia marked the end of a successful World Health Organization campaign of Sciences, Sofia, Bulgaria for smallpox eradication by vaccination on worldwide scale. Smallpox virus still exists today in some laboratories, specially designated for that purpose. The contemporary response in the treatment of the post-vaccine complications, which would occur upon enforcing new programs for mass-scale smallpox immunization, includes application of effective chemotherapeutics and their combinations. The goals are to provide the highest possible level of protection and safety of For personal use only. the population in case of eventual terrorist attack. This review describes the characteristic features of the poxviruses, smallpox vaccination, its adverse reactions, and poxvirus chemotherapy. Keywords: poxvirus, smallpox vaccine, post vaccine complications, inhibitors Characteristics of poxviruses Smallpox (variola) infection is caused by the smallpox virus. This virus belongs to the genus of Orthopoxvirus included in the Poxviridae family. Poxviruses are one of the largest and most complexly structured viruses, known so far. The genome of poxviruses consists of a linear two-chained DNA and its replication takes place in the cytoplasm of the infected cell. -

Generalized Vaccinia After Smallpox Vaccination with Concomitant Primary Epstein Barr Virus Infection

Case in Point Generalized Vaccinia After Smallpox Vaccination With Concomitant Primary Epstein Barr Virus Infection Jeremy Mandia, MD; and Kathryn Buikema, DO A patient presents with a spreading rash 9 days following inoculation with the smallpox vaccine. eneralized vaccinia (GV) is atopic dermatitis, or other rashes a rare, self-limiting complica- and reported no systemic symptoms. Figure 1. Satellite Lesions Seen tion of the smallpox vacci- His vitals also were within normal on Postvaccination Day 1 Gnation that is caused by the limits. A clinical diagnosis of inad- systemic spread of the virus from vertent inoculation (also termed ac- the inoculation site. The incidence cidental infection) with satellite of GV became rare after routine vac- lesions was made, and he was dis- cination was discontinued in the U.S. charged with counseling on wound in 1971 and globally in the 1980s care and close follow-up. Two days after the disease was eradicated.1,2 later, on postvaccination day 11, he However in 2002, heightened con- presented with new symptoms of a cerns for the deliberate release of the headache, fever, chills, diffuse my- smallpox virus as a bioweapon led algia, sore throat, and spreading er- the U.S. military to restart its small- ythematous macules, papules, and pox vaccination program for soldiers vesicles on his arms, chest, abdo- and public health workers.3,4 Here, men, back, legs, and face (Figures the authors describe a patient with 2A-2D). His vital signs were remark- concomitant GV and mononucleosis. able for tachycardia with heart rate of 100 bpm and a fever of 103º F (39.4º stabilized with conservative treat- CASE REPORT C). -

Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook

USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 U.S. ARMY MEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES FORT DETRICK FREDERICK, MARYLAND Emergency Response Numbers National Response Center: 1-800-424-8802 or (for chem/bio hazards & terrorist events) 1-202-267-2675 National Domestic Preparedness Office: 1-202-324-9025 (for civilian use) Domestic Preparedness Chem/Bio Helpline: 1-410-436-4484 or (Edgewood Ops Center – for military use) DSN 584-4484 USAMRIID’s Emergency Response Line: 1-888-872-7443 CDC'S Emergency Response Line: 1-770-488-7100 Handbook Download Site An Adobe Acrobat Reader (pdf file) version of this handbook can be downloaded from the internet at the following url: http://www.usamriid.army.mil USAMRIID’s MEDICAL MANAGEMENT OF BIOLOGICAL CASUALTIES HANDBOOK Sixth Edition April 2005 Lead Editor Lt Col Jon B. Woods, MC, USAF Contributing Editors CAPT Robert G. Darling, MC, USN LTC Zygmunt F. Dembek, MS, USAR Lt Col Bridget K. Carr, MSC, USAF COL Ted J. Cieslak, MC, USA LCDR James V. Lawler, MC, USN MAJ Anthony C. Littrell, MC, USA LTC Mark G. Kortepeter, MC, USA LTC Nelson W. Rebert, MS, USA LTC Scott A. Stanek, MC, USA COL James W. Martin, MC, USA Comments and suggestions are appreciated and should be addressed to: Operational Medicine Department Attn: MCMR-UIM-O U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) Fort Detrick, Maryland 21702-5011 PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION The Medical Management of Biological Casualties Handbook, which has become affectionately known as the "Blue Book," has been enormously successful - far beyond our expectations. -

Vaccinia Virus

APPENDIX 2 Vaccinia Virus • Accidental infection following transfer from the vac- cination site to another site (autoinoculation) or to Disease Agent: another person following intimate contact Likelihood of Secondary Transmission: • Vaccinia virus • Significant following direct contact Disease Agent Characteristics: At-Risk Populations: • Family: Poxviridae; Subfamily: Chordopoxvirinae; • Individuals receiving smallpox (vaccinia) vaccination Genus: Orthopoxvirus • Individuals who come in direct contact with vacci- • Virion morphology and size: Enveloped, biconcave nated persons core with two lateral bodies, brick-shaped to pleo- • Those at risk for more severe complications of infec- morphic virions, ~360 ¥ 270 ¥ 250 nm in size tion include the following: • Nucleic acid: Nonsegmented, linear, covalently ᭺ Immune-compromised persons including preg- closed, double-stranded DNA, 18.9-20.0 kb in length nant women • Physicochemical properties: Virus is inactivated at ᭺ Patients with atopy, especially those with eczema 60°C for 8 minutes, but antigen can withstand 100°C; ᭺ Patients with extensive exfoliative skin disease lyophilized virus maintains potency for 18 months at 4-6°C; virus may be stable when dried onto inanimate Vector and Reservoir Involved: surfaces; susceptible to 1% sodium hypochlorite, • No natural host 2% glutaraldehyde, and formaldehyde; disinfection of hands and environmental contamination with soap Blood Phase: and water are effective • Vaccinia DNA was detected by PCR in the blood in 6.5% of 77 military members from 1 to 3 weeks after Disease Name: smallpox (vaccinia) vaccination that resulted in a major skin reaction. • Progressive vaccinia (vaccinia necrosum or vaccinia • In the absence of complications after immunization, gangrenosum) recently published PCR and culture data suggest that • Generalized vaccinia viremia with current vaccines must be rare 3 weeks • Eczema vaccinatum after vaccination. -

Herpes Simplex Infections in Atopic Eczema

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.60.4.338 on 1 April 1985. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1985, 60, 338-343 Herpes simplex infections in atopic eczema T J DAVID AND M LONGSON Department of Child Health and Department of Virology University of Manchester SUMMARY One hundred and seventy nine children with atopic eczema were studied prospec- tively for two and three quarter years; the mean period of observation being 18 months. Ten children had initial infections with herpes simplex. Four children, very ill with a persistently high fever despite intravenous antibiotics and rectal aspirin, continued to produce vesicles and were given intravenous acyclovir. There were 11 recurrences among five patients. In two patients the recurrences were as severe as the initial lesions, and one of these children had IgG2 deficiency. Use of topical corticosteroids preceded the episode of herpes in only three of the 21 episodes. Symptomatic herpes simplex infections are common in children with atopic eczema, and are suggested by the presence of vesicles or by infected eczema which does not respond to antibiotic treatment. Virological investigations are simple and rapid: electron microscopy takes minutes, and cultures are often positive within 24 hours. Patients with atopic eczema are susceptible to features, and treatment of herpes simplex infections copyright. particularly severe infections with herpes simplex in a group of 179 children with atopic eczema. virus. Most cases are probably due to type 1,1 but eczema herpeticum due to the type 2 virus has been Patients and methods described,2 and the incidence of type 2 infections may be underestimated because typing is not usually Between January 1982 and September 1984 all performed. -

Draft Recommendations for Use of Smallpox Vaccine in a Pre-Event

Draft Recommendations for Use of Smallpox Vaccine in a Pre-Event Smallpox Vaccination Program: Supplemental Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) In June 2001, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made recommendations for the use of smallpox (vaccinia) vaccine to protect persons working with orthopoxviruses, and to prepare for a possible bioterrorism attack and for response to an attack involving smallpox.[1] Because of the terrorist attacks in the fall of 2001, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) asked the ACIP to review their previous recommendations for smallpox vaccination. These supplemental recommendations update the 2001 recommendations for vaccination of persons designated to respond or care for a suspected or confirmed case of smallpox. In addition, they clarify and expand the primary strategy for control and containment of smallpox in the event of an outbreak. Recommendations for vaccination of laboratory workers who directly handle recombinant vaccinia viruses derived from non-highly attenuated vaccinia strains, or other orthopoxviruses that infect humans (e.g., monkeypox, cowpox, vaccinia, and variola) remain unchanged.[1] The following recommendations were developed after formation of a joint Working Group of the ACIP and the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) in April 2002, joined in September 2002 by the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), and a series of public meetings and forums to review available data on smallpox, smallpox vaccine, smallpox control strategies, and other issues related to smallpox vaccination. Smallpox Transmission and Control Smallpox is transmitted from an infected person. Patients are most infectious during the first 7 to 10 days following rash onset; transmission can occur during the prodromal period just prior to rash onset, when lesions in the mouth ulcerate, releasing virus into oral secretions. -

Painful Bubbles

Osteopathic Family Physician (2018) 29 - 31 29 CLINICAL IMAGES Painful Bubbles Craig Bober, DO & Amy Schultz, DO Lankenau Hospital Family Medicine Residency A 25 year-old female with a past medical history of well controlled eczema presented to her primary care physician with a one week his- tory of a painful “bubbles” localized to her right antecubital fossa as seen in Figure 1. She noted that the new rash appeared to form over- night, was extremely painful, and would occasionally drain a clear liquid after scratching. It did not respond to her usual over-the-counter regimen of moisturizers prompting her to be evaluated. She had subjective fevers and malaise but denied oral or genital ulcers, vaginal discharge, dysuria, ocular irritation, visual disturbances, and upper respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. Review of systems was oth- erwise unremarkable. She had no other known medical problems, allergies, and denied drug and alcohol use. She denied any recent travel, sick contacts, pets, or OTC medications/creams. She was sexually active in a monogamous relationship for over a year. QUESTIONS 1. What is the most likely diagnosis? A. Cellulitis B. Eczema herpeticum C. Impetigo D. Primary varicella infection 2. Which test should be performed initally? A. Blood culture B. Direct fuorescent antibody staining FIGURE 1: C. Tzanck smear D. Wound culture 3. What is the best treatment? A. Acyclovir B. Augmentin C. Doxycycline D. Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin CORRESPONDENCE: Amy Schultz, DO | [email protected] 1877-5773X/$ - see front matter. © 2018 ACOFP. All rights reserved. 30 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 10, No. 3 | May/June, 2018 ANSWERS 1. -

Eczema Vaccinatum in Indiana’S Public Health Nurses Play a Vital Role in Protecting, Aiding, Child Resulting from and Educating Hoosiers

Volume 10, Issue 6 June 2007 Public Health Nurse Conference Article Page 2007 No. Public Health Nurse Tom Duszynski, BS Conference 2007 1 Eczema Vaccinatum in Indiana’s public health nurses play a vital role in protecting, aiding, Child Resulting from and educating Hoosiers. The Indiana State Department of Health Transmission of (ISDH) recognizes the contribution these nurses make to public health Vaccinia from in Indiana and assists their efforts by offering continuing education Smallpox Vaccinee opportunities, such as the annual Public Health Nurse Conference. with Tertiary Spread to the Mother 3 On June 8, more than 150 public A Decade of Indiana health nurses and Sentinel Influenza Data nursing students Surveillance 8 attended the 2007 ISDH Public Training Room 13 Health Nurse Conference. This Data Reports 14 year’s conference was the most well HIV Summary 14 attended in conference history. Disease Reports 15 Several years ago, the conference began as a “training day” to provide newly hired public health nurses with general education about public health responsibilities within local health departments. The conference has consistently grown over the past several years, and new ideas and different topics have emerged based on suggestions from those who have attended. Conference planners have used participants’ input to restructure the program to meet the needs of public health nurses. This year’s conference was no exception. Deputy State Health Commissioner Mary Hill, an attorney and registered nurse, opened the conference by reminding public health nurses and nursing students of the important work they do every day for Hoosiers and how, since September 11, 2001, their roles and knowledge have changed and expanded to include the world of preparedness, again demonstrating the flexibility of public health nursing. -

Disseminated Herpes Simplex Virus: a Case of Eczema Herpeticum Causing Viral Encephalitis C Finlow1, J Thomas2

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2018; 48: 36–9 | doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.108 CASE OF THE QUARTER Disseminated herpes simplex virus: a case of eczema herpeticum causing viral encephalitis C Finlow1, J Thomas2 ClinicalEczema herpeticum is a dermatological emergency causing a mortality Correspondence to: of up to 10% if untreated. It frequently presents in a localised form and C Finlow Abstract rarely disseminates via haematogenous spread with pulmonary, hepatic, Noble’s Hospital ocular and neurological manifestations. Although it commonly appears on a Strang background of atopic dermatitis, many other dermatological conditions have Douglas IM4 4RJ been described preceding this disease. Eczema herpeticum can be easily Isle of Man mistaken for folliculitis and is often treated accordingly with antibacterial drugs; therefore patients will often deteriorate before a diagnosis of eczema herpeticum has been considered. Email: c.fi [email protected] Keywords: eczema herpeticum, herpes simplex, Kaposi’s vericelliform eruption, rash, toxic confusional state, viral encephelitis Patient consent: obtained Declaration of interests: No confl ict of interests declared Background top of the chest and back and eventually to all four limbs. In places the rash produced serous and yellow fl uids. Eczema herpeticum (EH) was initially described by Moriz Kaposi in 1887 and is also known as Kaposi varicelliform On admission the patient was being treated with oral eruption.1 It can be a dermatological emergency manifesting fl ucloxacillin and amoxicillin for folliculitis, after initial as a generalised vesicular eruption in a toxic patient with presentation in the community. After being admitted this high morbidity and mortality. It is often associated with a pre- was changed to intravenous fl ucloxacillin, intravenous existing eczema diagnosis and for this reason it has a higher benzylpenicillin and topical fusidic acid for presumed incidence rate in children; however, it is also common in the folliculitis unresponsive to oral antibiotics. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0221523 A1 Tseng Et Al

US 2009.022 1523A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0221523 A1 Tseng et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 3, 2009 (54) NORTH-2'-DEOXY-METHANO- (86). PCT No.: PCT/US2O06/02O894 CARBATHYMIDNES AS ANTIVIRAL AGENTS AGAINST POXVIRUSES S371 (c)(1), (2), (4) Date: Apr. 3, 2009 (76) Inventors: Christopher K. Tseng, Related U.S. Application Data Burtonsville, MD (US); Victor E. (60) Provisional application No. 60/684.811, filed on May Marquez, Montgomery Village, 25, 2005. MD (US) Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. Correspondence Address: A 6LX 3L/7072 (2006.01) KNOBBE, MARTENS, OLSON & BEAR, LLP A6IP3L/20 (2006.01) 2040 MAINSTREET, FOURTEENTH FLOOR (52) U.S. Cl. .......................................................... S14/SO IRVINE, CA 92.614 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 11/920,881 A method for the prevention or treatment of poxvirus infec tion by administering an effective amount of an antiviral agent comprising cyclopropanated carbocyclic 2'-deoxy (22) PCT Filed: May 25, 2006 nucleoside to an individual in need thereof is provided. Patent Application Publication Sep. 3, 2009 Sheet 2 of 3 US 2009/022 1523 A1 HSV-2 TK Goalpox TK humonl TK VV TK VOriod TK monkeypox TK fowlpox TK HSV-1 K african swine fever virus TK VZV TK EBV TK FIF2 Patent Application Publication Sep. 3, 2009 Sheet 3 of 3 US 2009/022 1523 A1 CC (N)-MCT CDV VC – -2 48.61 site - 2322 2027 . US 2009/022 1523 A1 Sep. 3, 2009 NORTH-2-DEOXY. breaks depended on the isolation of infected individuals and METHANOCARBATHYMIDNES AS the vaccination of close contacts. -

Human Herpes Viruses 10/06/2012

Version 2.0 Human Herpes Viruses 10/06/2012 Name comes from the Greek 'Herpein' - 'to creep' = chronic/latent/recurrent infections. Types • HHV-1: Herpes simplex type I • HHV-2: Herpes simplex type II • HHV-3: Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) • HHV-4: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) • HHV-5: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) • HHV-6: Human herpesvirus type 6 (HBLV) • HHV-7: Human herpesvirus type 7 • HHV-8: Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) They belong to the following three families: • Alphaherpesviruses: HSV I & II; VZV • Betaherpesviruses: CMV, HHV-6 and HHV-7 • Gammaherpesviruses: EBV and HHV-8 Herpes simplex virus types I and II (HHV1 & 2) Primary infection usually by 2yr of age through mucosal break in mouth, eye or genitals or via minor abrasions in the skin. Asymptomatic or minor local vesicular lesions. Local multiplication → viraemia and systemic infection → migration along peripheral sensory axons to ganglia in the CNS → subsequent life-long latent infection with periodic reactivation → virus travels back down sensory nerves to surface of body and replicates, causing tissue damage: Manifestations of primary HSV infection • Systemic infection , e.g. fever, sore throat, and lymphadenopathy may pass unnoticed. If immunocompromised it may be life-threatening pneumonitis, and hepatitis. • Gingivostomatitis: Ulcers filled with yellow slough appear in the mouth. • Herpetic whitlow: Finger vesicles. Often affects childrens' nurses. • Traumatic herpes (herpes gladiatorum): Vesicles develop at any site where HSV is ground into the skin by brute force. E.g. wrestlers. • Eczema herpeticum: HSV infection of eczematous skin; usually children. • Herpes simplex meningitis: This is uncommon and usually self-limiting (typically HSV II in women during a primary attack) • Genital herpes: Usually HSV type II • HSV keratitis: Corneal dendritic ulcers. -

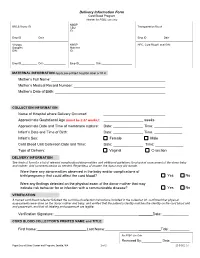

Delivery Information Form Cord Blood Program Header for PSBC Use Only NMDP BBCS Donor ID______CBU Transportation Box #______ID

Delivery Information Form Cord Blood Program Header for PSBC use only NMDP BBCS Donor ID________________________ CBU Transportation Box #____________________ ID: Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Virology NMDP HPC, Cord Blood Local DIN: Samples Maternal DIN: ID: Emp ID___________ Date_______________ Emp ID___________ Date_____________________ MATERNAL INFORMATION Apply pre-printed hospital label or fill in Mother’s Full Name: Mother’s Medical Record Number: Mother’s Date of Birth: COLLECTION INFORMATION Name of Hospital where Delivery Occurred: Approximate Gestational Age (must be ≥ 37 weeks): _ weeks Approximate Date and Time of membrane rupture: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Infant’s Date and Time of Birth: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Infant’s Sex: Female Male Cord Blood Unit Collection Date and Time: Date: _______________ Time: ______________ Type of Delivery: Vaginal C-section DELIVERY INFORMATION See back of form for a list of relevant complications/abnormalities and additional guidelines for physical assessment of the donor baby and mother. Add comments below as needed. Regardless of answer, the donor may still donate. Were there any abnormalities observed in the baby and/or complications of birth/pregnancy that could affect the cord blood? Yes No Were any findings detected on the physical exam of the donor mother that may indicate risk behavior for or infection with a communicable disease? Yes No VERIFICATION A trained cord blood collector followed the cord blood collection instructions included in the collection kit, confirmed that physical assessments were done on the donor mother and baby, and verified that the patient’s identity matches the identity on the cord blood unit and paperwork, and that all labeling and paperwork are legible.