Kunapipi 30 (2) 2008 Full Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering

Verge 5 Blatter 1 Chant Down Babylon: the Rastafarian Movement and Its Theodicy for the Suffering Emily Blatter The Rastafarian movement was born out of the Jamaican ghettos, where the descendents of slaves have continued to suffer from concentrated poverty, high unemployment, violent crime, and scarce opportunities for upward mobility. From its conception, the Rastafarian faith has provided hope to the disenfranchised, strengthening displaced Africans with the promise that Jah Rastafari is watching over them and that they will someday find relief in the promised land of Africa. In The Sacred Canopy , Peter Berger offers a sociological perspective on religion. Berger defines theodicy as an explanation for evil through religious legitimations and a way to maintain society by providing explanations for prevailing social inequalities. Berger explains that there exist both theodicies of happiness and theodicies of suffering. Certainly, the Rastafarian faith has provided a theodicy of suffering, providing followers with religious meaning in social inequality. Yet the Rastafarian faith challenges Berger’s notion of theodicy. Berger argues that theodicy is a form of society maintenance because it allows people to justify the existence of social evils rather than working to end them. The Rastafarian theodicy of suffering is unique in that it defies mainstream society; indeed, sociologist Charles Reavis Price labels the movement antisystemic, meaning that it confronts certain aspects of mainstream society and that it poses an alternative vision for society (9). The Rastas believe that the white man has constructed and legitimated a society that is oppressive to the black man. They call this society Babylon, and Rastas make every attempt to defy Babylon by refusing to live by the oppressors’ rules; hence, they wear their hair in dreads, smoke marijuana, and adhere to Marcus Garvey’s Ethiopianism. -

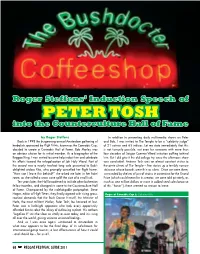

Peter Tosh Into the Counterculture Hall of Fame

Roger Steffens’ Induction Speech of PETER TOSH into the Counterculture Hall of Fame by Roger Steffens In addition to presenting daily multi-media shows on Peter Back in 1998 the burgeoning annual Amsterdam gathering of and Bob, I was invited to The Temple to be a “celebrity judge” herbalists sponsored by High Times, known as the Cannabis Cup, of 21 sativas and 63 indicas. Let me state immediately that this decided to create a Cannabis Hall of Fame. Bob Marley was is not humanly possible, not even for someone with more than an obvious choice for its initial member. As a biographer of the four decades of Saigon-Commie-Weed initiation puffing behind Reggae King, I was invited to come help induct him and celebrate him. But I did give it the old college try, once the afternoon show his efforts toward the re-legalization of Jah Holy Weed. Part of was concluded. Andrew Tosh was an almost constant visitor to the award was a nearly two-foot long cola presented to Bob’s the aerie climes of The Temple – five stories up a terribly narrow delighted widow Rita, who promptly cancelled her flight home. staircase whose boards were thin as rulers. Once we were there, “How can I leave this behind?” she asked me later in her hotel surrounded by shelves of jars of strains in contention for the Grand room, as she rolled a snow cone spliff the size of a small tusk. Prize (which could mean for its creator, we were told privately, as Ten years later, the Hall broadened to include other bohemian much as one million dollars or more in added seed sales because fellow travelers, and changed its name to the Counterculture Hall of this “honor”), there seemed no reason to leave. -

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648 Nonviolence Centre Australia dedicates 30th January, Martyrs’ Day to all those Martyrs who were sacrificed for their just causes. I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. -Mahatma Gandhi February 2016 | Non-Violence News | 1 Mahatma Gandhi’s 5 Teachings to bring about World Peace “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, with lies within our hearts — a force of love and thought, acted and inspired by the vision of humanity evolving tolerance for all. Throughout his life, Mahatma toward a world of peace and harmony.” - Dr. Martin Luther Gandhi fought against the power of force during King, Jr. the heyday of British rein over the world. He transformed the minds of millions, including my Have you ever dreamed about a joyful world with father, to fight against injustice with peaceful means peace and prosperity for all Mankind – a world in and non-violence. His message was as transparent which we respect and love each other despite the to his enemy as it was to his followers. He believed differences in our culture, religion and way of life? that, if we fight for the cause of humanity and greater justice, it should include even those who I often feel helpless when I see the world in turmoil, do not conform to our cause. History attests to a result of the differences between our ideals. -

Legal Consciousness and Resistance in Carribean Seasonal Agricultural Workers

Legal Consciousness and Resistance in Carribean Seasonal Agricultural Workers Smith, Adrian A. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, Volume 20, Number 2, 2005, pp. 95-122 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jls/summary/v020/20.2smith.html Access Provided by University of Montreal at 06/13/11 2:01PM GMT Legal Consciousness and Resistance in Carribean Seasonal Agricultural Workers Adrian A. Smith * No chains around my feet, but I'm not free. I know I am bound here in captivity. And I've never known happiness, and I've never known sweet caresses. Still, I’ll be always laughing like a clown. Won't someone help me? Cause, sweet life, I've, I've got to pick myself from off the ground, yeah.1 Introduction The idea that seasonal agricultural workers are ignorant of prevailing labour standards in Canada and, by extension, consensual participants in their own exploitation has gained momentum in recent years. While the debate over workers and consent in liberal capitalist societies is far from new, and legal scholars (broadly speaking) have not hesitated to join in, there is a need to explore the debate anew in light of the worker legal ignorance claim. An enthralling, relatively new area of study falling under the rubric of legal consciousness provides a basis on which to carry out the exploration. Specifically, scholars interested in the relationship between law and society (or, to avoid “playing favourites,” the other way around) must take account of the emerging field of inquiry devoted to the legal consciousness of individuals who are not “legal professionals.” In what is essentially a Law and Society take on the study of legal consciousness, the so-called “constitutive paradigm” has plenty to say about legal ignorance and knowledge, or consciousness, and how it shapes everyday life. -

Tarrus Riley “I Have to Surprise You

MAGAZINE #18 - April 2012 Busy Signal Clinton Fearon Chantelle Ernandez Truckback Records Fashion Records Pablo Moses Kayla Bliss Sugar Minott Jah Sun Reggae Month Man Free Tarrus Riley “I have to surprise you. The minute I stop surprising you we have a problem” 1/ NEWS 102 EDITORIAL by Erik Magni 2/ INTERVIEWS • Chantelle Ernandez 16 Michael Rose in Portland • Clinton Fearon 22 • Fashion Records 30 104 • Pablo Moses 36 • Truckback Records 42 • Busy Signal 48 • Kayla Bliss 54 Sizzla in Hasparren SUMMARY • Jah Sun 58 • Tarrus Riley 62 106 3/ REVIEWS • Ital Horns Meets Bush Chemists - History, Mystery, Destiny... 68 • Clinton Fearon - Heart and Soul 69 Ras Daniel Ray, Tu Shung • 149 Records #1 70 Peng and Friends in Paris • Sizzla In Gambia 70 Is unplugged the next big thing in reggae? 108 • The Bristol Reggae Explosion 3: The 80s Part 2 71 • Man Free 72 In 1989 MTV aired the first episode of the series MTV Unplugged, a TV show • Tetrack - Unfinished Business 73 where popular artists made new versions of their own more familiar electron- • Jah Golden Throne 74 Anthony Joseph, Horace ic material using only acoustic instrumentation. It became a huge success • Ras Daniel Ray and Tu Shung Peng - Ray Of Light 75 Andy and Raggasonic at and artists and groups such as Eric Clapton, Paul McCartney and Nirvana per- • Peter Spence - I’ll Fly Away 76 Chorus Festival 2012 formed on the show, and about 30 unplugged albums were also released. • Busy Signal - Reggae Music Again 77 • Rod Taylor, Bob Wasa and Positive Roots Band - Original Roots 78 • Cos I’m Black Riddim 79 110 Doing acoustic versions of already recorded electronic material has also been • Tarrus Riley - Mecoustic 80 popular in reggae music. -

The Social Impact of Social Funds in Jamaica

w Ps Z. q POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 2970 Public Disclosure Authorized The Social Impact of Social Funds in Jamaica Public Disclosure Authorized A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Participation, Targeting, and Collective Action in Community-Driven Development Vijayendra Rao Ana Marta Ibdfiez Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Development Research Group Poverty Team February 2003 POLIcy RESEARCH WORKINC, PAIIER 2970 Abstract Rao and lbanez develop an evaluation method that majority of communities. By the end of the construction combines qualitative evidence with quantitative survey process, however, 80 percent of the community data analyzed with propensity score methods on matched expressed satisfaction with the outcome. An analysis of samples to study the impact of a participatory the determinants of participation shows that better community-driven social fund on preference targeting, educated and better networked individuals dominate the collective action, and community decisionmiakiig. The process. Propensity score analysis reveals that the JSIF data come from a case stidy of five pairs of comMunities has had a causal impact on improvements in trust and the in Jamaica where one commnunity in the pair has received capacity for collective action, but these gains are greater funds from the Jamaica social investimient fund USIF) for elites within the communiity. Both JSIF and non-JSIF while the other has not-but has been picked to match communities are more likely now to make decisions that the funded community in its social and econlomilic affect their lives which indicates a broad-based effort to characteristics. The qualitative data reveal that the social promote participatory development in the countrv, but fund process is elite-driven and decisioninakinig tends to JSIF communiities do not show highier levels of be dominated by a small group of motivated individuals. -

440-413-0247

Open Noon to past sunset OPEN Sunday-ThursdaySun-Thurs 12-6 ALL and Midnight on Fridays YEAR! & Saturdays Visit us for your next Vacation or Get-Away! Four Rooms Complete with Private Hot Tubs 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfi eld, Ohio Three Rooms at $80 & Outdoor Patios 440.415.0661 One Suite at $120 www.bucciavineyard.com JOIN US FOR LIVE ENTERTAINMENT ALL Live Entertainment Fridays & Saturdays! WEEKEND! Appetizers & Full Entree www.debonne.com Menu See Back Cover See Back Cover For Full Info For Full Info www.grandrivercellars.com 2 www.northcoastvoice.com • (440) 415-0999 June 24 - July 15, 2015 Debonne Vineyards to host the First Annual Seafood & Wine Festival Debonne Vineyards, Ohio’s largest estate winery, is planning their fi rst annual Seafood & Wine Festival set for Friday, July 17th from 5-11 p.m. The festival will feature their award winning estate wines paired with delicious small plates from area restaurants including Rennick’s Meat Market, Grand River Cellars Winery & Connect 534 was designed around creating and marketing new events Restaurant, and Scales & Tails Food Truck, just along State Route 534; The City of to name a few. Each will feature a couple of Geneva, Geneva Township, Geneva- different dishes to offer to the public for a small on-the-Lake, and Harpersfield fee. If you are not a seafood fan, not to worry, Township. Connect 534 is working the Grill at Debonne will also be featuring their hard to promote local businesses and regular menu as well. The festival itself is free involve the community in new and but their will be a small parking donation to the revitalized events and programs. -

The Bob Marley Effect: More Than Just Words Juleen S

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-19-2014 The Bob Marley Effect: More Than Just Words Juleen S. Burke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Burke, Juleen S., "The Bob Marley Effect: More Than Just Words" (2014). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 1923. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/1923 The Bob Marley Effect: More Than Just Words By: Juleen S. Burke Thesis Advisors: Monsignor Dennis Mahon, Ph. D. Dr. Albert Widman Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts in Strategic Communication Seton Hall University South Orange, NJ The Bob Marley Effect 2 Abstract This study explores the legacy of Robert Nesta Marley through a comparison of his influence in Jamaica and the United States. The recognition that Bob Marley received, both during his life and after his death, is comparatively different between the two countries. As iconic as Marley is, why is his message and legacy different in the United States and most of his recognition not received till after his death? The researcher explores how Marley’s message was received in the two countries and whether his audience understood his philosophy and message in the same way. Results indicate that the communication of his thoughts were heard somewhat differently in Jamaica and the United States. Finally, this study presents recommendations for future research. The Bob Marley Effect 3 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to God, who is the head of my life. -

It a Go Dread Inna Switzerland 1

It a go dread inna Switzerland 1 It a go dread inna Switzerland a.1. Introduction Pour tous ceux, et ils sont nombreux, qui découvrent le reggae en Suisse aujourd’hui, en plein retour en force du genre, tout peut sembler une évidence : cette musique est mondialement connue, son plus illustre représentant une icône planétaire que certains n’hésitent pas à exploiter pour vendre des chaussures ou du savon. Plusieurs magasins spécialisés existent à travers le pays, les concerts se succèdent semaine après semaine, sans même parler des soirées qui fleurissent dans les lieux les plus improbables. Des Suisses écoutent du reggae, en collectionnent, en passent en soirées, en jouent au sein de groupes, en produisent sur leur propre label, promeuvent des artistes jamaïquains. Et même parmi les, très largement majoritaires, non-amateurs, rares sont ceux pour qui l’évocation de ce genre musical n’évoque ne serait-ce qu’un réducteur tissu de clichés. Quoi de plus naturel en apparence ? Cependant, si l’histoire s’encombrait de calculs de probabilités, les chances pour que la musique des ghettos de Kingston arrive jusqu’à des oreilles helvétiques étaient pour ainsi dire nulles. En effet, mis à part le lien musical qui fait l’objet de ce mémoire, tenter de tracer une ligne directe entre ces deux pays distants de dix mille kilomètres paraît laborieux. Géographiquement, historiquement, culturellement et économiquement, rappelons que le PIB par habitant de la Suisse est vingt-quatre fois supérieur à celui de la Jamaïque1, ils n’ont rien en commun. Il existe certes, pour un œil ou une oreille avertis, quelques minces, et somme toute anecdotiques, liens transatlantiques entre deux terres que tout oppose. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY The complete list of all sources consulted in the making of this book offers a comprehensive over- view of the literature and other materials available about reggae, Rastafari, Bob Marley, and other topics covered herein. Due to the fleeting nature of the Internet, where websites might change or dis- appear at any given time, online sources used at the time of writing might not be available any longer. The bibliography can also be found on the website of the book at www.reggaenationbook.com. Books History and Heritage (pp. 326-335). Routledge. Bennett, A. (2001). Cultures of Popular Music. Open University Press. Adejumobi, S. A. (2007). The History of Ethiopia. Biddle, I., & Knights, V. (Eds.) (2007). Music, National Greenwood Press. Identity and the Politics of Location: Between the Global Akindes, S. (2002). Playing It “Loud and Straight”. and the Local. Ashgate. Reggae, Zouglou, Mapouka, and Youth Bonacci, G. (2015). From Pan-Africanism to Rastafari: Insubordination in Côte d’Ivoire. In M. Palmberg African American and Caribbean ‘Returns’ & A. Kirkegaard (Eds.), Playing with Identities in to Ethiopia. In G. Prunier & E. Ficquet (Eds.), Contemporary Music in Africa (pp. 86-103). Nordic Understanding Contemporary Ethiopia: Monarchy, Africa Institute. Revolution and the Legacy of Meles Zenawi (pp. 147- Alleyne, M. (2009). Globalisation and Commercialisation 158). Hurst & Company. of Caribbean Music. In T. Pietila (Ed.), World Music Boot, A., & Salewicz, C. (1995). Bob Marley. Songs of Roots and Routes. Studies across Disciplines in the Freedom. Bloomsbury. Humanities and Social Sciences 6 (pp. 76-101). Helsinki Bordowitz, H. (2004). Every Little Thing Gonna Be Alright: Collegium for Advanced Studies. -

Religion and Revolution in the Lyrics of Bob Marley" Jan Decosmo, Asst

"Religion and Revolution in the Lyrics of Bob Marley" Jan DeCosmo, Asst. Professor of Humanities Florida A&M University, Tallahassee, Florida Caribbean Studies Assn. Conference, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, May 1994 (working copy, not for publication) In one of his many interviews, Bob Marley made the statement that reggae music had always been there, and that what made his music important was the lyrics. "Yes, it's necessary to understand the lyrics," he insisted [Time Will Tell 1992]. One connection of roots reggae to an earlier Caribbean tradition--specifically, calypso--is this emphasis on meaningful lyrics. According to Billy Bergman in his book, Hot Sauces: Pop, Reggae and Latin, this partiality for meaningful lyrics can be traced back to the African griot. He writes: Africans, brought as slaves to the island of TrinicW—the birthplace of calpyso--found the griot tradition a useful way of saying things that were not to be broadcoast in other ways. Diatribes against their oppressors could be couched in verse. The African tradition of ridicule songs was also maintained in after-work song sessions in which different work gangs praised themselves and made fun of others. [Later] . the political and social happenings of the Eastern Caribbean, and the world, were composed and commented upon in calypso lyrics. World wars were discussed, and legendary figures such as Roosevelt praised or condemned according to the views of the singers. Black news from around the world was especially noted. The living newspaper tradition of calypso continues to this day. [Bergman 1985:57] After reading this description, I was struck by a comment I remembered Marley had made to an interviewer about his music: "Reggae music" he said, "is a people music.