Oral History Interview with Fritz Eichenberg, 1964 December 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quaker Affirmations 1

SSttuuddeenntt NNootteebbooookk ffir r A m e a k t A Course i a of Study for o u n Q Young Friends Suggested for Grades 6 - 9 Developed by: First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] wwQw.indyfriends.org QQuuaakkeerr AAffffiirrmmaattiioonn:: AA CCoouurrssee ooff SSttuuddyy ffoorr YYoouunngg FFrriieennddss Course Conception and Development: QRuth Ann Hadley Tippin - Pastor, First Friends Meeting Beth Henricks - Christian Education & Family Ministry Director Writer & Editor: Vicki Wertz Consultants: Deb Hejl, Jon Tippin Pre- and Post-Course Assessment: Barbara Blackford Quaker Affirmation Class Committee: Ellie Arle Heather Arle David Blackford Amanda Cordray SCuagrogl eDsonteahdu efor Jim Kartholl GraJedde Ksa y5 - 9 First Friends Meeting 3030 Kessler Boulevard East Drive Indianapolis, IN 46220-2913 317.255.2485 [email protected] www.indyfriends.org ©2015 December 15, 2015 Dear Friend, We are thrilled with your interest in the Quaker Affirmation program. Indianapolis First Friends Meeting embarked on this journey over three years ago. We moved from a hope and dream of a program such as this to a reality with a completed period of study when eleven of our youth were affirmed by our Meeting in June 2015. This ten-month program of study and experience was created for our young people to help them explore their spirituality, discover their identity as Quakers and to inform them of Quaker history, faith and practice. While Quakers do not confirm creeds or statements made for them at baptism, etc, we felt it important that young people be informed and af - firmed in their understanding of who they are as Friends. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

VII. Dorothy Day and the Arts

VII. Dorothy Day and the Arts Dorothy Day was known for her appreciation of the arts. The great Russian writers Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky were early inspirations and models for Day, and the famed American playwright Eugene O’Neill was a personal friend. Day herself was a novelist and playwright, as well as a journalist and activist. She notably recognized, nurtured, and provided a vehicle (through the Catholic Worker newspaper) for the visual talents of Ade Bethune and Fritz Eisenberg. Day’s sacramental vision of the world asserted that God had made it both good and beautiful, and the arts helped to communicate that fundamental truth. Questions to Consider: 1. Dorothy Day was particularly influenced by her reading of the great Russian novelists Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose work is often deeply religious. Can you think of literature that you have read which has influenced your own social consciousness or the direction of your faith commitment? Do you think that literature or art in general can support a sense of vocation or call? If so, what might this say regarding our choices about what we read and how what we consume - in terms of art, media, or ideas - shapes who we are? 2. What is your experience of art in relation to the church? Have you seen art used as a way of reflecting the teaching or ideals of the church? Or have you witnessed a strain between the church and the arts, with involvement in the arts seen as a secular (even sometimes dangerous) endeavor? In your experience, are there certain arts that are more or less welcome or more or less represented in the church? 3. -

Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

A Communist Newspaper for Hungarian-Americans: The Strange World of the Uj Elore Thomas L. Sakmyster On November 6, 1921 the first issue of a newspaper called the Uj Elore (New Forward) appeared in New York City.1 This paper, which was published by the Hungarian Language Federation of the American Communist Party (then known as the Workers Party), was to appear daily until its demise in 1937. With a circulation ranging between 6,000 and 10,000, the Uj Elore was the third largest newspaper serving the Hungarian-American community.2 Furthermore, the Uj Elore was, as its editors often boasted, the only daily Hungarian Communist newspaper in the world. Copies of the paper were regularly sent to Hungarian subscri- bers in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, Buenos Aires, and, on occasion, even smuggled into Budapest. The editors and journalists who produced the Uj Elore were a band of fervent ideologues who presented and inter- preted news in a highly partisan and utterly dogmatic manner. Indeed, this publication was quite unlike most American newspapers of the time, which, though often oriented toward a particular ideology or political party, by and large attempted to maintain some level of objectivity. The main purpose of Uj Elore, as later recalled by one of its editors, was "not the dissemination of news but agitation and propaganda."3 The world as depicted by writers for the Uj Elore was a strange and distorted one, filled with often unintended ironies and paradoxes. Readers of the newspaper were provided, in issue after issue, with sensational and repetitive stories about the horrors of capitalism and fascism (especially in Hungary and the United States), the constant threat of political terror and oppression in all countries of the world except the Soviet Union, and the misery and suffering of Hungarian-American workers. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

Tamwag Fawf000053 Lo.Pdf

A LETTER FROM AMERICA By Pam Flett- WILL be interested in hearing what you think of Roosevelt’s foreign policy. When he made the speech at Chicago, I was startled and yet tremendously thrilled. It certainly looks as if something will have to be done to stop Hitler and Mussolini. But I wonder what is behind Roosevelt's speech. What does he plan to do? And when you get right down to it, what can we do? It’s easy to say “Keep out of War,” but how to keep out? TREAD in THE FIGHT that the ‘American League is coming out with a pamphlet by Harty F. Ward on this subject—Neutrality llready and an American sent in Peace my order. Policy. You I’ve know you can hardly believe anything the newspapers print these days_and I’m depending gare end ors on hare caer Phiets. For instance, David said, hational, when we that read i¢ The was Fascist_Inter- far-fetched and overdone. But the laugh’s for on him, everything if you can that laugh pamphlet at it- Fe dered nigiae th fact, the pamphiot is more up- iendalainow than Fodey'eipener eso YOUR NEXT YEAR IN ART BUT I have several of the American League pamphlets—Women, War and Fascism, Youth Demands WE'VE stolen a leaf from the almanac, which not only tells you what day it is but gives you Peace, A Blueprint for Fascism advice on the conduct of life. Not that our 1938 calendar carries instructions on planting-time (exposing the Industrial Mobiliza- tion Plan)—and I’m also getting But every month of it does carry an illustration that calls you to the struggle for Democracy and Why Fascism Leads to War and peace, that pictures your fellow fighters, and tha gives you a moment’s pleasure A Program Against War and Fascism. -

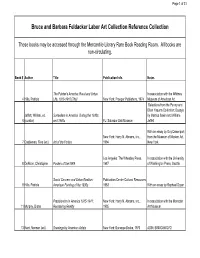

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH and MAKING of the US ART CULTURE DURING the 1930’S

MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’s A Master’s Thesis By GÖZDE PINAR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 To My Parents…. MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by GÖZDE PINAR In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Edward P. Kohn Thesis Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Kenneth Weisbrode Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dennis Bryson Examining Committee Member Approved by the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences. -------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Pınar, Gözde M.A., Department of History, Bilkent University Supervisor: Assist. -

The Independent Voice of the Visual Arts Volume 35 Number 1, October 2020

The Independent Voice of the Visual Arts Volume 35 Number 1, October 2020 Established 1973 ART & POLITICS $15 U.S. ART AND POLITICS COVER CREDITS Front: Gran Fury, When A Government Turns Its Back On Its People; Joan_de_art & crew, Black Lives Matter;Hugo Gellert: Primary Accumulation 16 Back: Chris Burke and Ruben Alcantar, Breonna Taylor, Say Her Name!!!, Milwaukee; Sue Coe, Language of the Dictator; Lexander Bryant, Opportunity Co$t, Gran Fury, Kissing Doesn’t Kill. Established 1973 Vol. 35, No. 1 October 2020 Contents ARTICLES 3 Art and Politics: 39 COVID-19 and the Introduction Creative Process(es) Two more Interviews 5 Art of the Black Lives from Chicago Matter Movement Michel Ségard compiles BLM-related 39 Introduction art from across the country. 40 Stevie Hanley Stevie Hanley is a practicing artist and 11 It Can Happen Here— an instructor at the Art Institute of An Anti-Fascism Project Chicago. He is also the organizer of the Siblings art collective. Stephen F. Eisenman and Sue Coe mount their multimedia resistance to the Donald Trump administration. 43 Patric McCoy Patric McCoy is an art collector and 19 Have you given up hope co-founder of the arts non-profit for a cure? Diasporal Rhythms, an organization Paul Moreno revisits Gran Fury, an focused on the art of the African ‘80s art collective that responded to Diaspora. AIDS in unabashedly political ways. 25 In Tennessee, Art Itself Is Protest Kelli Wood leads us through Nashville’s art scene, advocating change to the tune of Dolly Parton’s “Down on Music REVIEWS Row.“ 47 “Problem Areas” 32 Iconoclasm Then Luis Martin/The Art Engineer reviews the first solo show from painter Paul and Now Moreno at New York’s Bureau of Gen- Thomas F.X. -

Down from the Ivory Tower: American Artists During the Depression

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression Susan M. Eltscher College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Eltscher, Susan M., "Down from the ivory tower: American artists during the Depression" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625189. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a5rw-c429 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOWN FROM THE IVORY TOWER: , 4 ‘ AMERICAN ARTISTS DURING THE DEPRESSION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Susan M. Eltscher APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^jiuu>0ur> H i- fc- bbcJ^U i Author Approved, December 1982 Richard B. Sherman t/QOJUK^r Cam Walker ~~V> Q ' " 9"' Philip J/ Fuiyigiello J DEDICATION / ( \ This work is dedicated, with love and appreciation, to Louis R. Eltscher III, Carolyn S. Eltscher, and Judith R. Eltscher. ( TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACRONYMS................... .......................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................... -

The Spirit of the Sixties: Art As an Agent for Change

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year Student Scholarship & Creative Works 2-27-2015 The pirS it of the Sixties: Art as an Agent for Change Kyle Anderson Dickinson College Aleksa D'Orsi Dickinson College Kimberly Drexler Dickinson College Lindsay Kearney Dickinson College Callie Marx Dickinson College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Elizabeth, et al. The Spirit of the Sixties: Art as an Agent for Change. Carlisle, Pa.: The rT out Gallery, Dickinson College, 2015. This Exhibition Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship & Creative Works at Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year by an authorized administrator of Dickinson Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Kyle Anderson, Aleksa D'Orsi, Kimberly Drexler, Lindsay Kearney, Callie Marx, Gillian Pinkham, Sebastian Zheng, Elizabeth Lee, and Trout Gallery This exhibition catalog is available at Dickinson Scholar: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work/21 THE SPIRIT OF THE SIXTIES Art as an Agent for Change THE SPIRIT OF THE SIXTIES Art as an Agent for Change February 27 – April 11, 2015 Curated by: Kyle Anderson Aleksa D’Orsi Kimberly Drexler Lindsay Kearney Callie Marx Gillian Pinkham Sebastian Zheng THE TROUT GALLERY • Dickinson College • Carlisle, Pennsylvania This publication was produced in part through the generous support of the Helen Trout Memorial Fund and the Ruth Trout Endowment at Dickinson College. -

Dorothy Day and Friends La Salle University Art Museum

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues La Salle University Art Museum Fall 1996 Dorothy Day and Friends La Salle University Art Museum Brother Daniel Burke FSC Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation La Salle University Art Museum and Burke, Brother Daniel FSC, "Dorothy Day and Friends" (1996). Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues. 35. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/exhibition_catalogues/35 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the La Salle University Art Museum at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Museum Exhibition Catalogues by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dorothy Day and Friends La Salle University Art Museum Fall, 1996 Dorothy Day and Friends La Salle University Art Museum Fall, 1996 The installation of a new, wood-carved portrait of Dorothy Day in the La Sa/te Museum is a good occasion to recall a particular network of the University’s friends. First, of course, there is Dorothy herself who visited us several times in the ‘60s and early 70’s—and packed the theater with students drawn to her challenging and encouraging message. There is also her long-term friend Fritz Eichenberg, who illustrated her autobiography and many issues of the Worker. There are her committed followers, the staff of Houses of Hospitality here in Philadelphia, with whom a number of our students work—Martha Battzett as well, one of the Houses major helpers and one of our own “art angels.