Juan Downey's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First U.S. Survey of Chilean Artist Juan Downey to Open at Bronx Museum of the Arts

FIRST U.S. SURVEY OF CHILEAN ARTIST JUAN DOWNEY TO OPEN AT BRONX MUSEUM OF THE ARTS Video and Photographic Installations, Paintings, and Drawings shed light on Downey’s Career Bronx, NY , DATE – Beginning February 9, 2012 The Bronx Museum of the Arts will present Juan Downey: The Invisible Architect , the first U.S. survey of the pioneering video artist Juan Downey. On view through May 20, 2012, the exhibition brings together more than 100 works from Downey’s expansive career, from his early experimental work with art and technology to his groundbreaking video art from the 1970s through the 1990s, the exhibition will include drawings, paintings, video and photographic installations, and the artist’s notebooks, which have never before been on view. “Downey revolutionized the field of video art and pioneered an art form that has had continued relevance for contemporary artists working today,” said Bronx Museum of the Arts Director Holly Block. “As a Chilean, Downey maintained a connection with Latin American culture throughout the many decades he lived and worked in New York. These dual influences give his work a special resonance with the Bronx Museum and with our community. In addition, Downey has exhibited at the Bronx Museum before, making this exhibition a homecoming of sorts.” Formally trained as an architect, Downey began experimenting with different art forms when he moved from Paris to Washington DC in 1965. He developed a strong interest in the concept of invisible energy and shifted from object-based artistic practice to an experiential approach, seeking to combine interactive performance with sculpture and video, a transition the exhibition explores. -

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards

2015 Regional Economic Development Council Awards Governor Andrew M. Cuomo 1 2 Table of Contents Regional Council Awards Western New York .........................................................................................................................12 Finger Lakes ...................................................................................................................................28 Southern Tier ..................................................................................................................................44 Central New York ..........................................................................................................................56 Mohawk Valley ...............................................................................................................................68 North Country .................................................................................................................................80 Capital Region ................................................................................................................................92 Mid-Hudson ...................................................................................................................................108 New York City ............................................................................................................................... 124 Long Island ................................................................................................................................... -

Performing Power

Rebecca Belmore: Performing Power Jolene Rickard The aurora borealis or northern lights, ignited by the intersection of elements at precisely the right second, burst into a fire of light on black Anishinabe nights. For some, the northern lights are simply reflections caused by hemispheric dust, but for others they are power. Rebecca Belmore knows about this power; her mother, Rose, told her so.1 Though the imbrication of Anishinabe thinking was crucial in her formative years in northern Ontario, Belmore now has a much wider base of observation from Vancouver, British Columbia. Her role as 2 transgressor and initiator—moving fluidly in the hegemony of the west reformulated as "empire " —reveals how conditions of dispossession are normalized in the age of globalization. Every country has a national narrative, and Canada is better than most at attempting to integrate multiple stories into the larger framework, but the process is still a colonial project. The Americas need to be read as a colonial space with aboriginal or First Nations people as seeking decolonization. The art world has embraced the notion of transnational citizens, moving from one country to the next by continuously locating their own subjectivities in homelands like China, Africa and elsewhere. As a First Nations or aboriginal person, Belmore's homeland is now the modern nation of Canada; yet, there is reluctance by the art world to recognize this condition as a continuous form of cultural and political exile. The inclusion of the First Nations political base is not meant to marginalize Belmore's work, but add depth to it. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE JANUARY 2019 Name: Alejandro Garcia Address: 303 Crawford Avenue Syracuse, NY 13224 Telephone: Office: (315) 443-5569 Born: Brownsville, Texas April 1, 1940 Academic Unit: School of Social Work Academic Specialization: Social Policy, Gerontology, Human Diversity Education: Ph.D., Social Welfare Policy, The Heller School for Advanced Studies in Social Welfare, Brandeis University (1980) Dissertation title: "The Contribution of Social Security to the Adequacy ` of Income of Elderly Mexican Americans." Adviser: Professor James Schulz. M.S.W., Social Work, School of Social Work, California State University at Sacramento (1969) B.A., The University of Texas at Austin (1963) Graduate, Virginia Satir's International AVANTA Process Institute, Crested Butte, Colorado (1987) Membership in Professional and Learned Societies: Academy of Certified Social Workers American Association of University Professors Council on Social Work Education The Gerontological Society of America National Association of Social Workers Association of Latino and Latina Social Work Educators Professional Employment: October 2015-present Jocelyn Falk Endowed Professor of Social Work, School of Social Work Syracuse University 1983 to present: Professor (Tenured), School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1994-2002 Chair, Gerontology Concentration, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY Garcia cv p. 2 1999, 2000 Adjunct faculty, Smith College School for Social Work Northampton, MA 1984-91 Faculty, Elderhostel, Le Moyne College, Syracuse, NY 1978-1983 Associate Professor, School of Social Work, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 1975-1978 Instructor, Graduate School of Social Work Boston College, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Social Work, Graduate School of Social Work, Boston University, Boston, MA 1977-1978 Special Lecturer in Social Policy. -

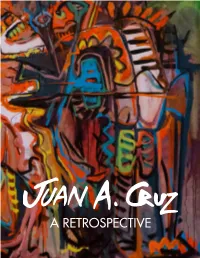

A Retrospective

A RETROSPECTIVE A RETROSPECTIVE This catalogue was published on the occasion of the exhibition Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective Organized by DJ Hellerman and on view at the Everson Museum of Art, May 4 – August 4, 2019 Copyright Everson Museum of Art, 2019 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019946139 ISBN 978-0-9978968-3-1 Catalogue design: Ariana Dibble Photo credits: DJ Hellerman Cover image: Juan Cruz, Manchas, 1986, oil on canvas, 48 x 72 inches, Everson Museum of Art; Gift of Mr. John Dietz, 86.89 Inside front image by Dave Revette. Inside back image by Julie Herman. Everson Museum of Art 401 Harrison Street Syracuse, NY 13202 www.everson.org 2 LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Honorable Minna R. Buck Stephen and Betty Carpenter The Dorothy and Marshall M. Reisman Foundation The Gifford Foundation Laurence Hoefler Melanie and David Littlejohn Onondaga Community College Neva and Richard Pilgrim Punto de Contacto – Point of Contact Samuel H. Sage Dirk and Carol Sonneborn Martin Yenawine 3 FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Spanning five decades, Juan A. Cruz: A Retrospective presents the work of one of Syracuse’s most beloved artists. Juan Cruz settled in Syracuse in the 1970s and quickly established himself as an important part of the local community. He has designed and painted numerous murals throughout the city, taught hundreds of children and teens how to communicate their ideas through art, and assumed the role of mentor and friend to too many to count. Juan’s art, and very person, are part of the fabric of Syracuse, and it is an honor to be able to share his accomplishments with the world through his exhibition at the Everson Museum of Art. -

Brian Jungen Friendship Centre

BRIAN JUNGEN FRIENDSHIP CENTRE Job Desc.: AGO Access Docket: AGO0229 Client: AGO A MESSAGE FROM Supplier: Type Page: STEPHAN JOST, Trim: 8.375" x 10.5" Bleed: MICHAEL AND SONJA Live: Pub.: Membership Mag ad KOERNER DIRECTOR, Colour: CMYK Date: April 2019 AND CEO Insert Date: Ad #: AGO0229_FP_4C_STAIRCASE DKT./PROJ: AGO0229 ARTWORK APPROVAL Artist: Studio Mgr: Production: LESS EQUALS MOREProofreader: Creative Dir.: Art Director: Copywriter: The AGO is having a moment. There’s a real energy when I walkTranslator: through the galleries, thanks to the thousands of visitors who have experienced the AGOAcct. for Service: the first time – or their hundredth. It is an energy that reflects our vibrant and diverseClient: city, and one that embraces the undeniable power of art to change the world. And weProof: want 1 more2 3 4people 5 6 to7 Final experience it and make the AGO a habit. PDFx1a Laser Proof Our membership is generous and strong. Because of your support, on May 25 we’re launching a new admission model to remove barriers and encourage deeper relationships with the AGO. The two main components are: • Everyone 25 and under can visit for free • Anyone can purchase a pass for $35 and visit as many times as they’d like for a full year Without your vital support as an AGO Member, this new initiative wouldn’t be possible. Thanks to you, a teenager might choose us to impress their date or a tired dad might take his children for a quick 30-minute visit, knowing he can come back again and again. You will continue to enjoy the special benefits of membership, including Members’ Previews that give you first access to our amazing exhibitions. -

9New York State Days

NEW YORK 3 REGIONS. 3 NIGHTS EACH. 9 INCREDIBLE DAYS. Explore a brand new self driving tour from New York City all STATE IN the way across the state, including the Hudson Valley, Syracuse and Buffalo Niagara. Countless sites. Countless memories. DAYS See New York State in 9 days. To book your reservation, contact your local travel agent or tour provider. DAY 1-3 HUDSON VALLEY DAY 4-6 SYRACUSE DAY 7-9 BUFFALO NIAGARA 9DAYS 1-3 IN THE HUDSON VALLEY Dutchess County Roosevelt-Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Hudson River views, Great Estates, farms & farm markets, FDR Presidential Library & Museum is America’s first events and festivals, cultural & culinary attractions, presidential library and the only one used by a sitting president. boutique & antique shopping – only 90 minutes from NYC! FDR was the 32nd President of the U.S. and the only president dutchesstourism.com elected to four terms. He was paralyzed by polio at age 39, led the country out of the Great Depression, and guided America The Culinary through World War II. fdrlibrary.org Institute of Eleanor Roosevelt’s Val-Kill is the private cottage home of one America of the world’s most influential women. nps.gov/elro The premier culinary Vanderbilt Mansion is Frederick W. Vanderbilt’s Gilded Age home school offers student- surrounded by national parkland on the scenic Hudson River. guided tours and dining nps.gov/vama at four award-winning restaurants. Walkway Over ciarestaurantgroup.com the Hudson The bridge (circa 1888) is a NY State Historic Park; 64.6m above the Hudson and 2.06km across, making it the world’s longest elevated pedestrian bridge. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

The Social and Environmental Turn in Late 20Th Century Art

THE SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURN IN LATE 20TH CENTURY ART: A CASE STUDY OF HELEN AND NEWTON HARRISON AFTER MODERNISM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN MODERN THOUGHT AND LITERATURE AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY LAURA CASSIDY ROGERS JUNE 2017 © 2017 by Laura Cassidy Rogers. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/gy939rt6115 Includes supplemental files: 1. (Rogers_Circular Dendrogram.pdf) 2. (Rogers_Table_1_Primary.pdf) 3. (Rogers_Table_2_Projects.pdf) 4. (Rogers_Table_3_Places.pdf) 5. (Rogers_Table_4_People.pdf) 6. (Rogers_Table_5_Institutions.pdf) 7. (Rogers_Table_6_Media.pdf) 8. (Rogers_Table_7_Topics.pdf) 9. (Rogers_Table_8_ExhibitionsPerformances.pdf) 10. (Rogers_Table_9_Acquisitions.pdf) ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Zephyr Frank, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Gail Wight I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Ursula Heise Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. -

Karl Hubbuch (Karlsruhe 1891 – 1979 Karlsruhe)

Nummer 397 Kunstwerk des Monats April 2018 Karl Hubbuch (Karlsruhe 1891 – 1979 Karlsruhe) Erinnerungen an den 04. Januar 1925, 1925, Lithographie 30,8 x 23,1 cm (Darstellung) 32,5 x 24,9 cm (Blatt), Inv. Nr. L 638 „Der Welt den Spiegel vorhalten“, mit diesem Zitat aus durch einen collageartigen Aufbau mit mehreren Erzähl- Shakespeares Hamlet umschrieb Karl Hubbuch die Intenti- ebenen gelungen. on seiner Kunst (Brief an Franz Roh vom 12. Februar 1953). Der Blick aus dem Fenster, angedeutet durch den Vorhang in der oberen linken Ecke, fällt auf eine Hochzeitsge- Wie bei vielen Arbeiten der 1920er Jahre hat Hubbuch sellschaft. Die Leserichtung führt den Blick weiter über auf dem Blatt mit den „Erinnerungen an den 04. Januar ein Gebäude zu dem Brautpaar in einem Auto. Durch 1925“ einen autobiographischen Inhalt in einen größeren zwei große Blüten, die vermutlich auf einer Fensterbank gesellschaftlichen Rahmen eingebettet. Dies ist ihm stehen, sind vier kleinteiligere Szenen isoliert. Die Berliner Theaterbühnen hatten den jungen Hubbuch Aufruf zur Wahl der Demokratie dar. Damit spielte er zu einer solchen Komposition mit verschiedenen Bild- auf die politische Lage an, in der Hitler längst kein kleines strukturen und Maßstäben inspiriert. Während seiner Licht mehr war. Durch eine Unterredung am Tresen und Studienzeit an der Lehranstalt des Kunstgewerbemuseums der Beschilderung „Arbeits-Amt“ verdeutlichte er ein hatte er bis Kriegsausbruch viele Inszenierungen gesehen. weiteres gesellschaftliches Problem. Zudem schien Der Wechsel von der Großherzoglichen Badischen Aka- Hubbuch durch die Darstellung einer Frau mit grafischen demie in Karlsruhe nach Berlin wurde Hubbuch 1912 Blättern auf die eigene Lage des Künstlerdaseins zu durch die finanzielle Unterstützung seines bis dahin verweisen. -

Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

A Communist Newspaper for Hungarian-Americans: The Strange World of the Uj Elore Thomas L. Sakmyster On November 6, 1921 the first issue of a newspaper called the Uj Elore (New Forward) appeared in New York City.1 This paper, which was published by the Hungarian Language Federation of the American Communist Party (then known as the Workers Party), was to appear daily until its demise in 1937. With a circulation ranging between 6,000 and 10,000, the Uj Elore was the third largest newspaper serving the Hungarian-American community.2 Furthermore, the Uj Elore was, as its editors often boasted, the only daily Hungarian Communist newspaper in the world. Copies of the paper were regularly sent to Hungarian subscri- bers in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, Buenos Aires, and, on occasion, even smuggled into Budapest. The editors and journalists who produced the Uj Elore were a band of fervent ideologues who presented and inter- preted news in a highly partisan and utterly dogmatic manner. Indeed, this publication was quite unlike most American newspapers of the time, which, though often oriented toward a particular ideology or political party, by and large attempted to maintain some level of objectivity. The main purpose of Uj Elore, as later recalled by one of its editors, was "not the dissemination of news but agitation and propaganda."3 The world as depicted by writers for the Uj Elore was a strange and distorted one, filled with often unintended ironies and paradoxes. Readers of the newspaper were provided, in issue after issue, with sensational and repetitive stories about the horrors of capitalism and fascism (especially in Hungary and the United States), the constant threat of political terror and oppression in all countries of the world except the Soviet Union, and the misery and suffering of Hungarian-American workers. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T.