The Photographs of George Platt Lynes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

George Tooker David Zwirner

David Zwirner New York London Hong Kong George Tooker Artist Biography George Tooker (1920–2011) is best known for his use of the traditional, painstaking medium of egg tempera in compositions reflecting urban life in American postwar society. Born in Brooklyn, he received a degree in English from Harvard University before he began his studies at the Art Students League in 1943, where he worked under the regionalist painter Reginald Marsh. In 1944, Tooker met the artist Paul Cadmus, and they soon became lovers. Cadmus, sixteen years his senior, introduced Tooker to the artist Jared French, with whom he was romantically involved, and French’s wife, Margaret Hoening French, and the four of them traveled extensively throughout Europe and vacationed regularly together. Tooker appears in a number of the photographs taken by PaJaMa, the photographic collective formed by Cadmus and the Frenches, and he served as a model for Cadmus’s painting Inventor (1946). Cadmus and French introduced Tooker to the time-intensive medium of egg tempera, which would become his principal medium. Tooker’s career found early success, due in part to his friend Lincoln Kirstein, the co-founder of the New York City Ballet, encouraging the inclusion of his work in the Fourteen Americans (1946) and Realists and Magic-Realists (1950) exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art. In 1950, Subway (1950) entered the Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection—the artist’s first museum acquisition—and the following year he received his first solo exhibition at the Edwin Hewitt Gallery. Near the end of the 1940s, Tooker parted ways with Cadmus because of the latter’s ongoing relationship with the Frenches. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

George Platt Lynes David Zwirner

David Zwirner New York London Hong Kong George Platt Lynes Artist Biography Among the greatest photographers of the twentieth century, George Platt Lynes (1907–1955) developed a uniquely elegant and distinctive style of portraiture alongside innovative investigations of the erotic and formal qualities of the male nude body. Born and raised in New Jersey with his brother Russell, who would go on to become a managing editor at Harper’s Magazine, Lynes entertained literary ambitions in his youth. While at prep school in Massachusetts, where he studied beside future collaborator and New York City Ballet founder Lincoln Kirstein, he began a correspondence with the American writer Gertrude Stein, then living in Paris. Over a series of successive visits to Paris, he met Stein and her partner, Alice B. Toklas, who integrated him into their creative milieu. At their salons, he met such figures as the painter Pavel Tchelitchew, French writer André Gide, and the dancer Isadora Duncan. Accompanying him on many of these transatlantic journeys was a romantically involved couple consisting of writer Glenway Wescott and the publisher and future director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Monroe Wheeler, the latter of whom became Lynes’s lover. During a failed attempt to write a novel and a successful stint as the owner of a bookshop in New Jersey, Lynes began experimenting with a camera in 1929, photographing friends in his creative social circles in New York and Paris. Those early casual experiments would become a serious commitment to the medium. In 1931, he settled in New York, where his ménage à trois continued with Wheeler and Wescott, with all three sharing an apartment, an arrangement that lasted until 1943. -

Oral History Interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5

Oral history interview with Paul Cadmus, 1988 March 22-May 5 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Paul Cadmus on March 22, 1988. The interview took place in Weston, Connecticut, and was conducted by Judd Tully for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview JUDD TULLY: Tell me something about your childhood. You were born in Manhattan? PAUL CADMUS: I was born in Manhattan. I think born at home. I don't think I was born in a hospital. I think that the doctor who delivered me was my uncle by marriage. He was Dr. Brown Morgan. JUDD TULLY: Were you the youngest child? PAUL CADMUS: No. I'm the oldest. I's just myself and my sister. I was born on December 17, 1904. My sister was born two years later. We were the only ones. We were very, very poor. My father earned a living by being a commercial lithographer. He wanted to be an artist, a painter, but he was foiled. As I say, he had to make a living to support his family. We were so poor that I suffered from malnutrition. Maybe that was the diet, too. I don't know. I had rickets as a child, which is hardly ever heard of nowadays. -

Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

A Communist Newspaper for Hungarian-Americans: The Strange World of the Uj Elore Thomas L. Sakmyster On November 6, 1921 the first issue of a newspaper called the Uj Elore (New Forward) appeared in New York City.1 This paper, which was published by the Hungarian Language Federation of the American Communist Party (then known as the Workers Party), was to appear daily until its demise in 1937. With a circulation ranging between 6,000 and 10,000, the Uj Elore was the third largest newspaper serving the Hungarian-American community.2 Furthermore, the Uj Elore was, as its editors often boasted, the only daily Hungarian Communist newspaper in the world. Copies of the paper were regularly sent to Hungarian subscri- bers in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, Buenos Aires, and, on occasion, even smuggled into Budapest. The editors and journalists who produced the Uj Elore were a band of fervent ideologues who presented and inter- preted news in a highly partisan and utterly dogmatic manner. Indeed, this publication was quite unlike most American newspapers of the time, which, though often oriented toward a particular ideology or political party, by and large attempted to maintain some level of objectivity. The main purpose of Uj Elore, as later recalled by one of its editors, was "not the dissemination of news but agitation and propaganda."3 The world as depicted by writers for the Uj Elore was a strange and distorted one, filled with often unintended ironies and paradoxes. Readers of the newspaper were provided, in issue after issue, with sensational and repetitive stories about the horrors of capitalism and fascism (especially in Hungary and the United States), the constant threat of political terror and oppression in all countries of the world except the Soviet Union, and the misery and suffering of Hungarian-American workers. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

Tamwag Fawf000053 Lo.Pdf

A LETTER FROM AMERICA By Pam Flett- WILL be interested in hearing what you think of Roosevelt’s foreign policy. When he made the speech at Chicago, I was startled and yet tremendously thrilled. It certainly looks as if something will have to be done to stop Hitler and Mussolini. But I wonder what is behind Roosevelt's speech. What does he plan to do? And when you get right down to it, what can we do? It’s easy to say “Keep out of War,” but how to keep out? TREAD in THE FIGHT that the ‘American League is coming out with a pamphlet by Harty F. Ward on this subject—Neutrality llready and an American sent in Peace my order. Policy. You I’ve know you can hardly believe anything the newspapers print these days_and I’m depending gare end ors on hare caer Phiets. For instance, David said, hational, when we that read i¢ The was Fascist_Inter- far-fetched and overdone. But the laugh’s for on him, everything if you can that laugh pamphlet at it- Fe dered nigiae th fact, the pamphiot is more up- iendalainow than Fodey'eipener eso YOUR NEXT YEAR IN ART BUT I have several of the American League pamphlets—Women, War and Fascism, Youth Demands WE'VE stolen a leaf from the almanac, which not only tells you what day it is but gives you Peace, A Blueprint for Fascism advice on the conduct of life. Not that our 1938 calendar carries instructions on planting-time (exposing the Industrial Mobiliza- tion Plan)—and I’m also getting But every month of it does carry an illustration that calls you to the struggle for Democracy and Why Fascism Leads to War and peace, that pictures your fellow fighters, and tha gives you a moment’s pleasure A Program Against War and Fascism. -

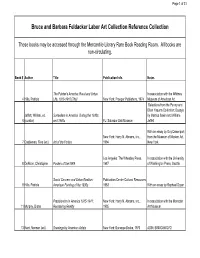

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

February 7, 2001

April 2019 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Keith de Lellis (212) 327-1482 [email protected] GEORGE PLATT LYNES PORTRAITS, NUDES, & DANCE APRIL 11 – MAY 23, 2019 Keith de Lellis Gallery showcases the portrait photography of noted fashion photographer and influential artist George Platt Lynes (American, 1907–1955) in its spring exhibition. Though largely concealed during his lifetime (or published under pseudonyms), Lynes’ male nude photographs are perhaps his most notable works today and inspired later artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Herb Ritts. Primarily self-taught, Lynes was influenced by Man Ray when he visited Paris in 1925, where he also met Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Wescott, and John Cocteau. Publisher Jack Woody wrote, “surrealism, neo-romanticism, and other European visual movements remained with him” when he returned to New York (Ballet: George Platt Lynes, Twelvetree Press, 1985). Lynes first exhibited with surrealist gallerist Julian Levy in 1932, and was featured at many galleries and museums in his lifetime, including three group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art. He opened his New York studio in 1933, finding great success in commercial portraiture for fashion magazines (Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, etc.) and local elites. The artist relocated to Los Angeles in 1946 to lead Vogue’s west coast studio for two years, photographing celebrities such as Katharine Hepburn and Gloria Swanson, before returning to New York to focus on personal work, disavowing commercial photography. While his commercial work allowed him to support himself and brought him great recognition as a photographer, it did not fulfill him creatively, leading the artist to destroy many of those negatives and prints towards the end of his life. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. [ANTHOLOGY] JOYCE, James. Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. (Edited by Robert McAlmon). 8vo, original printed wrappers. (Paris: Contact Editions Three Mountains Press, 1925). First edition, published jointly by McAlmon’s Contact Editions and William Bird’s Three Mountains Press. One of 300 copies printed in Dijon by Darantiere, who printed Joyce’s Ulysses. Slocum & Cahoon B7. With contributions by Djuna Barnes, Bryher, Mary Butts, Norman Douglas, Havelock Ellis, Ford Madox Ford, Wallace Gould, Ernest Hemingway, Marsden Hartley, H. D., John Herrman, Joyce, Mina Loy, Robert McAlmon, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. Includes Joyce’s “Work In Progress” from Finnegans Wake; Hemingway’s “Soldiers Home”, which first appeared in the American edition of In Our Time, Hanneman B3; and William Carlos Williams’ essay on Marianne Moore, Wallace B8. Front outer hinge cleanly split half- way up the book, not affecting integrity of the binding; bottom of spine slightly chipped, otherwise a bright clean copy. $2,250.00 BERRIGAN, Ted. The Sonnets. 4to, original pictorial wrappers, rebound in navy blue cloth with a red plastic title-label on spine. N. Y.: Published by Lorenz & Ellen Gude, 1964. First edition. Limited to 300 copies. A curious copy, one of Berrigan’s retained copies, presumably bound at his direction, and originally intended for Berrigan’s close friend and editor of this book, the poet Ron Padgett. -

Historic Tullamore Farm a True Town & Country Farm

AUCTION Historic Tullamore Farm A True Town & Country Farm September 20th 207.8+/- Acres Preserved Farmland Delaware Twp, Hunterdon County, NJ Private Pastoral Setting with Breathtaking Country and Delaware River Views • Located in the picturesque rolling Hunterdon County hillside and just steps to the Delaware River and Towpath Trail for walking, biking or riding horses. • Truly a diverse compound combining a lovely historic home site, equestrian center, guest cottages, event center, barns and farmland. • Wonderfully restored historic main stone house built in the 1800’s and later expanded features an open floor plan with expansive windows to take in the +/- beautiful rolling hills. 106.33 Acres • The main home features a chef’s kitchen with center island which opens to the dining room and great room with cathedral ceilings and French doors opening to an expansive patio. The master private wing features a spacious bedroom, cozy fireplace, dressing room, European en suite bath with soaking tub and office. There are two guest suites, plus two upstairs bedrooms with bathroom. • Host equestrian events! The Equestrian center includes indoor and outdoor riding arena, acres 101.47+/- Acres of paddocks, and two barns with 16 stalls plus apartment for trainer or laborers. • Rich productive soils. • The farm has been utilized as a grass-fed cattle operation and can easily be converted to a vineyard or other agritourism business. • Walk or Ride along the Delaware River towpath for access to Stockton, Lambertville, Frenchtown or cross the bridge