Whose Representative?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of India

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NOs.4444-4476 OF 2011 (Arising out of SLP(C)Nos.33123-33155 of 2010) Balchandra L. Jarkiholi & Ors. … Appellants Vs. B.S. Yeddyurappa & Ors. … Respondents WITH C.A.Nos…4522-4554/2011 @ SLP(C)Nos. 33185- 33217 of 2010 and C.A.Nos…4477-4509/2011 @ SLP(C)Nos.33533-33565 of 2010 J U D G M E N T ALTAMAS KABIR, J. 1. Leave granted. 2 2. All the above-mentioned appeals arise out of the order dated 10th October, 2010, passed by the Speaker of the Karnataka State Legislative Assembly on Disqualification Application No.1 of 2010, filed by Shri B.S. Yeddyurappa, the Legislature Party Leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party in Karnataka Legislative Assembly, who is also the Chief Minister of the State of Karnataka, on 6th October, 2010, under Rule 6 of the Karnataka Legislative Assembly (Disqualification of Members on Ground of Defection) Rules, 1986, against Shri M.P. Renukacharya and 12 others, claiming that the said respondents, who were all Members of the Karnataka Legislative Assembly, would have to be disqualified from the membership of the House under the Tenth Schedule of the Constitution of India. In order to understand the circumstances in which the Disqualification Application came to be filed by Shri Yeddyurappa for disqualification of the 13 named persons from the membership of the Karnakata 3 Legislature, it is necessary to briefly set out in sequence the events preceding the said application. 3. On 6th October, 2010, all the above-mentioned 13 members of the Karnataka Legislative Assembly, belonging to the Bharatiya Janata Party, hereinafter referred to as the “MLAs”, wrote identical letters to the Governor of the State indicating that they had been elected as MLAs on Bharatiya Janata Party tickets, but had become disillusioned with the functioning of the Government headed by Shri B.S. -

A Brief Report of the Business

A BRIEF REPORT OF THE BUSINESS TRANSACTED DURING THE FIRST SESSION (16, 22, 23, 24 MARCH, 2017) OF THE SEVENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA GOA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT PORVORIM – GOA 2017 1 A BRIEF REPORT OF THE BUSINESS TRANSACTED DURING THE FIRST SESSION (16, 22, 23, 24 MARCH, 2017) OF THE SEVENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA GOA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT PORVORIM – GOA 2017 2 PREFACE This booklet contains statistical information of the business transacted by the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa during its First Session, which was held on the 16, 22, 23 and 24 March, 2017. PORVORIM – GOA 31/3/2017 N.B. SUBHEDAR SECRETARY, LEGISLATURE 3 A BRIEF REPORT OF THE BUSINESS TRANSACTED BY THE SEVENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA DURING ITS FIRST SESSION, 2017, WHICH WAS HELD ON THE 16TH, 22ND, 23RD AND THE 24TH MARCH, 2017 1. INTRODUCTION Dr. (Smt.) Mridula Sinha, the Hon. Governor of Goa, vide Order dated the 15th March, 2017, summoned the First Session of the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa, which commenced on the 16th March, 2017, at 11 30 AM at the Assembly Hall, Porvorim, Goa. The National Anthem was played at the commencement of the Session. The First Session, 2017 of the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa had 4 sittings and had a duration of 6 hours and 8 minutes and has transacted an effective and a significant business. 2. DURATION OF THE SITTINGS OF THE HOUSE The total duration of the sittings of the House was 6 hours and 8 minutes. -

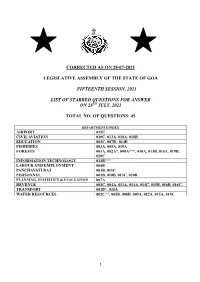

Corrected As on 28-07-2021 Legislative Assembly of The

CORRECTED AS ON 28-07-2021 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA FIFTEENTH SESSION, 2021 LIST OF STARRED QUESTIONS FOR ANSWER ON 28TH JULY, 2021 TOTAL NO. OF QUESTIONS: 45 DEPARTMENTS INDEX AIRPORT 015C CIVIL AVIATION 010C, 013A, 018A, 018B EDUCATION 003C, 007B, 014B FISHERIES 003A, 005A, 019A FORESTS 001A, 002A*, 008A***, 010A, 013B, 016A, 019B, 020C INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 011B*** LABOUR AND EMPLOYMENT 004B PANCHAYATI RAJ 003B, 011C PERSONNEL 001B, 010B, 013C, 020B PLANNING, STATISTICS & EVALUATION 007A REVENUE 001C, 004A, 011A, 014A, 014C, 015B, 016B, 016C, TRANSPORT 002B*, 020A WATER RESOURCES 002C**, 005B, 008B, 009A, 012A, 015A, 019C 1 SL. MEMBER QUESTION DEPARTMENT NO. NOS 001A FORESTS 1. SHRI CLAFASIO DIAS 001B PERSONNEL 001C REVENUE 002A* FORESTS 2. SHRI VINODA PALIENCAR 002B* TRANSPORT 002C** WATER RESOURCES 003A FISHERIES 3. SHRI SUBHASH SHIRODKAR 003B PANCHAYATI RAJ 003C EDUCATION 004A REVENUE 4. SMT. ALINA SALDANHA 004B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 005A FISHERIES 5 SHRI JOSE LUIS ALMEIDA 005B WATER RESOURCES 6. 006A FORESTS SHRI VIJAI SARDESAI 006B WATER RESOURCES 006C TRANSPORT 007A PLANNING, STATISTICS AND SHRI TICLO GLENN SOUZA EVALUATION 7. 007B EDUCATION 008A*** TRANSFERRED 8. SHRI PRASAD GAONKAR 008B WATER RESOURCES 9. SHRI DIGAMBAR KAMAT 009A WATER RESOURCES 010A FORESTS 10 SHRI ATANASIO MONSERRATE 010B PERSONNEL 010C CIVIL AVIATION 011A REVENUE 11 SHRI ANTONIO FERNANDES 011B*** TRANSFERRED 011C PANCHAYATI RAJ 12 SHRI CHURCHILL ALEMAO 012A WATER RESOURCES 013A CIVIL AVIATION 13 SHRI ROHAN KHAUNTE 013B FORESTS 013C PERSONNEL -

Mopa Airport Woes

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 Mopa Airport Woes Debating the Proposed Airport in North Goa KENNETH BO NIELSEN Vol. 50, Issue No. 25, 20 Jun, 2015 Kenneth Bo Nielsen ([email protected]) is a postdoctoral research fellow, University of Bregen, Norway. A proposed new airport in North Goa has brought to the fore the old North Goa–South Goa feud. With the current Bharatiya Janata Party government determined to make the project a success, they could ride roughshod over concerns, environmental as well as political. If the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led state government has its way, Goa will have a new operational international airport in five years from now. The proposed airport will be located on the Mopa plateau in Pernem taluka in North Goa, near the Maharashtra border. But although the project is backed by strong political and commercial interests, it has encountered stiff opposition from other quarters. This commentary examines how the proposed Mopa airport has polarised public opinion in India’s smallest state. From Dabolim to Mopa The only airport in Goa today is the centrally-located Dabolim international airport. Dabolim was built by the Portuguese as a civilian airport in 1955—the Portuguese military air force never had a presence in Goa—but only months after the Indian Army had liberated Goa in December 1961, the airport was taken over by the Indian Navy’s air wing (Pais 2014: 217). Dabolim airport today is thus in effect a civilian enclave within a military airbase. The Indian Navy has shown no interest in relocating its base in Dabolim elsewhere, and has generally proven reluctant to relinquish more land for the expansion of civilian operations, even when a new, integrated terminal building was inaugurated in 2013. -

A Brief Report of the Business Transacted During the Fifteenth Session of the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State Of

A BRIEF REPORT OF THE BUSINESS TRANSACTED DURING THE FIFTEENTH SESSION (28TH, 29THAND 30TH JULY 2021) OF THE SEVENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA GOA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT PORVORIM-GOA 2021 1 PREFACE This booklet contains statistical information of the business transacted by the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa during its Fifteenth Session, which was held from 28th, 29th, and 30th July 2021. Ms. Namrata Ulman 30/7/2021 Secretary 2 Brief Report of the Business transacted by the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa during its Fifteenth Session held from 28th July to 30th July 2021 In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause (1) of Article 174 of the Constitution of India, the Hon. Governor of Goa vide Order dated the 28th June, 2021, summoned the Fifteenth Session of the Seventh Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa, which commenced on 28th July 2021, at 11 30 AM at the Assembly Hall, Porvorim, Goa. The National Anthem was played at the commencement of the Session. The August House had a duration of 72 hours and 15 minutes during its 3 sittings which was held during the period from 28th, 29th, and 30th July 2021. 2. DURATION OF THE SITTINGS OF THE HOUSE The total duration of the sittings of the House was 72 hours and 15 minutes Sl. Dates of sitting Duration of sitting Total duration of the sitting No Hours Minutes 1. 28.7.2021 11:30 am to 1:09 pm 1 39 2:30 pm to 4:01 pm 1 31 4:30 pm to 1:09 am 8 39 2. -

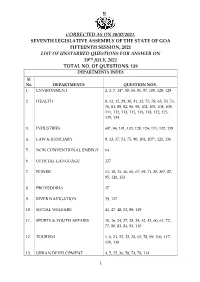

Corrected As on 30/07/2021

CORRECTED AS ON 30/07/2021. SEVENTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA FIFTEENTH SESSION, 2021 LIST OF UNSTARRED QUESTIONS FOR ANSWER ON 30TH JULY, 2021 TOTAL NO. OF QUESTIONS: 139 DEPARTMENTS INDEX Sl. No. DEPARTMENTS QUESTION NOS. 1. ENVIRONMENT 2, 3, 7, 14*, 50, 54, 91, 97, 100, 128, 129 2. HEALTH 8, 12, 15, 29, 30, 31, 32, 55, 59, 63, 70, 73, 76, 81, 88, 92, 96, 98, 102, 105, 108, 109, 111, 112, 113, 115, 116, 118, 122, 125, 135, 134 3. INDUSTRIES 68*, 94, 101, 103, 120, 124, 131, 132, 139 4. LAW & JUDICIARY 9, 13, 37, 53, 75, 90, 104, 107*, 123, 136 5. NON CONVENTIONAL ENERGY 64 6. OFFICIAL LANGUAGE 137 7. POWER 11, 18, 25, 46, 66, 67, 69, 71, 85, 86*, 87, 95, 126, 133 8. PROVEDORIA 17 9. RIVER NAVIGATION 39, 127 10. SOCIAL WELFARE 41, 47, 48, 52, 89, 119 11. SPORTS & YOUTH AFFAIRS 10, 16, 24, 27, 28, 34, 42, 43, 60, 61, 72, 77, 80, 83, 84, 93, 110 12. TOURISM 1, 6, 21, 23, 33, 38, 65, 78, 99, 106, 117, 130, 138 13. URBAN DEVELOPMENT 4, 5, 35, 36, 58, 74, 79, 114 1 14. WOMEN & CHILD 19, 20, 22, 26, 40, 44, 45, 49, 51, 56, 57, DEVELOPMENT 62, 82, 121 * Transferred to other Department. 2 MEMBERS INDEX SL MEMBER LAQ NO. NO . 1. SHRI ALEIXO REGINALDO LOURENCO 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14*, 15, 136, 137 2. SHRI ANTONIO FERNANDES 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 3. -

O. G. Series III No. 43.Pmd

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2018-20 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 23rd January, 2020 (Magha 3, 1941) SERIES III No. 43 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY GOVERNMENT OF GOA 1. No bidder shall be admitted to the auction unless he/she makes a deposit of Rs. 100/- as Department of Finance an earnest money separately in respect of Revenue & Control Division each zone. The earnest money can be Office of the Commissioner of Excise deposited in the Department between 27th __ January, 2020 to 04th February, 2020 and thereafter deposits shall also be accepted at Public Notice the place of auction before commencement of No. CE/15/2017-18/Cashew/Exc/3905 auctions of respective Talukas. It is hereby notified to all concerned that public 2. At the close of the auction the deposits of auctions of rights to manufacture liquor from earnest money made by the unsuccessful cashew juice in respect of various zones located in bidders shall be refunded to them against the North and South Goa in between bidders who undertake to manufacture the maximum quantity production of receipts of such deposits. of liquor from particular zones for cashew season of 3. The licence shall be granted to the bidder the year 2020, shall be held before the committee who shall undertake to manufacture the constituted under Rule 72(2) of Goa Excise Duty highest quantity of liquor of 25% under proof Rules, 1964 at Swami Vivekanand Hall, Panaji-Goa, or corresponding quantity of lesser strength and Ravindra Bhavan (Black Box Hall), Margao, after full payment of bid amount. -

Download Goa

For More Questions Click Here Q: Who is the Current Chief Minister of Goa ? (a) Digambar Kamat (b) Laxmikant Parsekar (c) Manohar Parrikar (d) None of These Ans: Manohar Parrikar Q: Who is the Current Governor of Goa ? (a) Om Prakash Kohli (b) Mridula Sinha (c) Margaret Alva (d) Smt. V. S. Ramadevi Ans: Mridula Sinha Q: Who is the Current Director general of police of Goa ? (a) Sudhir Yadav (b) Dr. Muktesh Chander (c) Sanjay Kumar, IPS (d) None of These Ans: Dr. Muktesh Chander Q: Which is the Goa state Animal ? (a) Gaur/Gavoredo in Konkani Bos gaurus (b) Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica (c) Blackbuck Antilope cervicapra (d) None of these Ans: Gaur/Gavoredo in Konkani Bos gaurus Q: Which is the Goa state Tree? (a) Chinar Platanus orientalis (b) Sacred fig Ficus religiosa (c) Asna Terminalia elliptica (d) None of These Ans: Asna Terminalia elliptica Q: Which is the Goa state Bird? (a) House sparrow Passer domesticus (b) Bastar hill myna Gracula religiosa peninsulari (c) Yellow-throated bulbul Pycnonotus xantholaemus (d) None of these Ans: Yellow-throated bulbul Pycnonotus xantholaemus Q: How long was the tenure of Laxmikant Parsekar (a) 5 years, 126 days (b) 1 years, 156 days (c) 2 years, 136 days (d) None of These Ans: 2 years, 126 days Q: Who is the first Governor of Goa ? (a) Sh. Bhagawan Sahay (b) Sh. Om Parkash (c) Lt. Gen. K. Bhadur Singh (d) Maj. Gen. K. S. Himmatsinhji Ans: Maj. Gen. K. S. Himmatsinhji Q: Who is the First Chief Justices of Goa ? (a) P.C.B. -

Indian Delegates and Advisers to International Labour Conference (1919-2016)

Indian Delegates and Advisers to International Labour Conference (1919-2016) Indian Delegates and Advisers 1919 Government Delegates Mr. Louis James Kershew, C.S.I., C.I.E., Secretary, Revenue and Statistics Department, India Office, London. Mr. Atul Chandra Chatterjee, C.I.E., I.C.S., Acting Chief Secretary, United Provinces Government. Adviser Mr. John David Frederick Engel, Chief Inspector of Factories, Bombay Presidency. Employers’ Delegate Mr. Alexander Robertson Murray, C.B.E., Chairman of the Indian Jute Mills Association. Workers’ Delegate Mr. Narayan Malhar Joshi, Secretary, Social Service League, Bombay. Adviser Mr. Bahman Pestonji Waddia, President, Madras Labour Union. 1920 Government Delegates Mr. L. J. Kershaw, C.S.I, C.I.E., Former Secretary to the Government of India, Secretary of the India Office, London. Capt. D. F. Vines, O.B.E., A.D.C., Royal Indian Marine, Director of the Arsenal at Calcutta. Technical Advisers Commander H. Hodgkinson, R. N., Karachi. Mr. J.E.P. Curry, J.P., Marine Department, Bombay. Shipowners’ Delegates Mr. A. Cameron, Of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Co., and the British India Steam Navigation, Company. Technical Advisers Mr. J. Taylor, Director of the River Steam Navigation Co., Ltd., London and Calcutta. Capt. C.S. Penny, Deputy Director of the Fleet of the British India Steam Navigation Company, Bombay. Mr. J. Melville, Deputy Administrator of the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company. Seamen’s Delegate Mr. A.M Mazarello, President of the Asiatic Seamen’s Union, Bombay. Technical Advisers Bhika Ahmed, Lascar Serang. Habiboola Elhamdeen, Fireman Serang. 1921 Government Delegates Mr. A. C. Chatterjee, C.I.E., I.C.S., Secretary to the Government of India, Department of Industries. -

Goa´S Democratic Becoming and the Absence of Mass Political Violence

Aureliano FERNANDES, Lusotopie 2003 : 331-349 Goa´s Democratic Becoming and the Absence of Mass Political Violence olitical change, it is presumed, especially in transitional or emerging nations of Asia and Africa, is likely to be prefaced by massive political Pviolence. This phenomena, it is believed, not only threatens viability of these nation states, and their capacity to function effectively, but also forces the discipline of comparative politics to evolve new conceptualization in order to understand this crisis (Sloan 1971 : 12). This emasculation occurs as a result of transition « from empire to nation », a price for « liberation » from coloniality. Violence, therefore, becomes one more rationalization for American and Eurocentric formulations of the failure of emerging Asian- Indian nation-states as integrating forces. Clearly, therefore, the post colonial challenge subsists in the entrenchment of new state formations in a colonial past and their potential to redefine society to create a space for the varied culture world of its people, asserting diverse identities. In the case of Goa, a lusotopic space, its historical fashioning, its multicultural ethos, despite its ethnological diversity, and more importantly its democratic political institutions, more specifically its bi-party system have managed political change without the aberration of large scale mass political violence, vindicating the cause of democracy and the fact that orderly change is possible in transitional societies. Ironically the phenomenology of the « new imperialism » of the 21st Century, betrayed by deleterious violence against nations and peoples, seems to suggest that democratic political institutions have met their annihilation in the « land of their birth ». Violence in politics The role of violence as a medium of political discourse has increased strikingly in South Asia, Far East, Africa and South America in the post colonial era. -

SERIES I No. 21 Goa Legislature Secretariat

Reg. No. GR/RNP/GOA/32 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 19th August, 2010 (Sravana 28, 1932) SERIES I No. 21 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY NOTE There are two Extraordinary issues to the Official Gazette, Series I No. 20 dated 12-8-2010, as follows:— (1) Extraordinary dated 13-8-2010 from pages 793 to 794 regarding modification of the timings of the GOA SANDS ONLINE Scheme– Not. No. JS(BUD)/32/2010 from Department of Finance ((Budget Division). (2) Extraordinary (No. 2) dated 16-8-2010 from pages 795 to 796 regarding Amendments to entries of Schedule I – Not. No. 30/1/2006-Fin(R&C)(13) from Department of Finance (Revenue & Control Division). INDEX Department Report/Notification Subject Pages 1. Goa Legislature Secretariat LA/LEGN/2010/1799 Second Report – Select Committee on the Goa 797 Co-operative Societies Act, 2010. 2. Inland & Waterways Not.- CP/H.S.O 138/2010 Alteration of the Port limits – Tiracol and Talpona. 873 Captain of Ports Captain & ex officio Joint Secretary 3. Personnel Not.- 1/25/86-PER(P. F. I.) R. R. – Commercial Tax. 874 Joint Secretary Goa Legislature Secretariat ___ LA/LEGN/2010/1799 The following Report which was presented in the Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa on 6th August, 2010 is hereby published for general information in pursuance of Rule-231 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business of the Goa Legislative Assembly. __________ FIFTH LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA SECOND REPORT OF SELECT COMMITTEE ON THE GOA CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETIES ACT, 2001 Presented to the House on 6th August, 2010 GOA LEGISLATURE SECRETARIAT ASSEMBLY HALL PORVORIM-GOA 797 OFFICIAL GAZETTE — GOVT. -

Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics

School of Social Sciences and Humanities Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics Jason Keith Fernandes A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Anthropology Supervisor: Professor Rosa Maria de Figueiredo Perez, Professora Associada com Agregação, ISCTE-University Institute of Lisbon June 2013 School of Social Sciences and Humanities Citizenship Experiences of the Goan Catholics Jason Keith Fernandes A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Anthropology Jury Doutora Maria Paula Gutierres Meneses Investigadora do Centro de Estudos Sociais da Universidade de Coimbra Doutora Pamila Gupta Senior Researcher the University of Witwatersrand Doutor Everton Vasconcelos Machado Investigador de Pós-Doutoramento do Centro de Estudos Comparatistas da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa Doutor Miguel de Matos Castanheira do Vale de Almeida, Professor Associado com Agregação do Departamento de Antropologia da ECSHumanas do ISCTE-IUL Doutora Rosa Maria Figueiredo Perez Professora Associada com Agregação do Departamento de Antropologia da ECSHumanas do ISCTE-IUL (Supervisor) Research project supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia June 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that the nature of the citizenship experience of the Catholics in the Indian state of Goa is the experience of those located between civil society and political society. This argument commences from the postulate that the recognition of Konkani in the Devanagari script as the official language of Goa, determined the boundaries of the state’s civil society.Through an ethnographic study of the contestations around the demand that the Roman script also be officially recognised, the thesis demonstrates how by deliberately excluding the Roman script for the language, the largely lower-caste and lower-class Catholic users of the script were denoted as less than authentic members of the legitimate civil society of the state.