Analysis and Performance Problems of Vítězslava Kaprálová’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 9 No.2/3, 1993

JOURNAL afthe AMERICAN VIOLA SOCIETY Chapter of THE INTERNATIONAL VIOLA SOCIETY Association for the Promotion of Viola Performance and Research Vol. 9 Nos. 2&3 1993 The Journal ofthe American Viola Society is a publication ofthat organization and is produced at Brigham Young University, © 1993, ISSN 0898-5987. The Journalwelcomes letters and articles from its readers. Editorial andAdvertising Office: BYU Music Harris Fine Arts Center Provo, UT 84602 (801) 378-4953 Fax: (801) 378-5973 Editor: David Dalton Assistant Editor: David Day Production: Helen Dixon JAVS appears three times yearly. Deadlines for copy and art work are March 1, July 1, and November 1; submissions should be sent to the editorial office. Ad rates: $100 full page, $85 two-thirds page, $65 halfpage, $50 one-third page, $35 one-fourth page. Classifieds: $25 for 30 words including address; $40 for 31-60 words. Advertisers will be billed after the ad has appeared. Payment to "American Viola Society" should be remitted to the editorial office. OFFICERS Alan de Vertich President School ofMusic University of So. California 830 West 34th Street Ramo Hall 112 Los Angeles, CA 90089 (805) 255-0693 Thomas Tatton Vice-President 2705 Rutledge Way Stockton, CA 95207 Pamela Goldsmith Secretary 11640 Amanda Drive Studio City, CA 91604 Ann Woodward Treasurer 209 w. University Ave. Chapel Hill, NC 27514 David Dalton Past President Editor, JA VS Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 BOARD Mary Arlin J~ffery Irvine John Kella William Magers Donald !v1cInnes Kathryn Plummer Dwight Pounds -

A Chronology of All Artists' Appearances with the Chamber

75 Years of Chamber Music Excellence: A Chronology of all artists’ appearances with the Chamber Music Society of Louisville st 1 Season, 1938 – 1939 Kathleen Parlow, violin and Gunnar Johansen, piano The Gordon String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Heermann Trio nd 2 Season, 1939 – 1940 The Budapest String Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet Marcel Hubert, cello and Harold Dart, piano rd 3 Season, 1940 – 1941 Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord and Lois Wann, oboe Belgian PianoString Quartet The Coolidge Quartet th 4 Season, 1941 – 1942 The Trio of New York The Musical Art Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet th 5 Season, 1942 – 1943 The Budapest String Quartet The Coolidge Quartet The Stradivarius Quartet th 6 Season, 1943 – 1944 The Budapest String Quartet Gunnar Johansen, piano and Antonio Brosa, violin The Musical Art Quartet th 7 Season, 1944 – 1945 The Budapest String Quartet The Pro Arte Quartet Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord th 8 Season, 1945 – 1946 The Musical Art Quartet Nikolai Graudan, cello and Joanna Graudan, piano Philip Manuel, harpsichord and Gavin Williamson, harpsichord The Budpest String Quartet th 9 Season, 1946 – 1947 The Louisville Philharmonic String Quartet with Doris Davis, piano The Albeneri Trio The Budapest String Quartet th 10 Season, 1947 – 1948 Alexander Schneider, violin and Ralph Kirkpatrick, harpsichord The Budapest String Quartet The London String Quartet The Walden String Quartet The Albeneri Trio th 11 Season, 1948 – 1949 The Alma Trio -

APRIL 2009 LIST See Inside for Valid Dates

tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 APRIL 2009 LIST See inside for valid dates Dear Customer As the weather here becomes positively agreeable and the evenings lengthen, we offer you a cornucopia of delights containing both new growth and old returning favourites in a seductively priced spring bouquet - we hope you cannot resist! The major new release this month is Angela Hewitt’s re-visit of the Bach 48, a fresh look at this masterpiece of the keyboard repertoire. The reports indicate a quite different approach from her original recordings a decade ago, resulting from her years of performing and living with this music - a ‘new-found freedom’ as Ms Hewitt calls it. We have made it available at a special price for this list, along with reductions on the whole of her Hyperion back catalogue. The LSO Live Gergiev Mahler series continues with Symphony no.8 recorded in the mammoth acoustic of St Paul’s Cathedral. DG, in this Handel year, provide us with the first ever studio recording of his neglected Ezio, first performed in London in 1732 and a fine example of ‘opera seria’. For fans of the Gheorghiu/Alagna duo, there is a fascinating new world premiere recording on the Larghetto label (see page 8) of excerpts from a little known opera by Vladimir Cosma, Marius and Fanny, inspired by the writings of Marcel Pagnol. As always, we have negotiated reduced price offers - HM Gold, Praga, Delphian, Accord, Handel sets on Hyperion, EMI Gemini and British Composers, and the Medici Arts DVD catalogue. Make the most of them. -

Annual Brochure 2016

· 2016 · www.ecma-music.com www.ecma-music.com EUROPEAN CHAMBER MUSIC ACADEMY Oslo 2015 Vilnius 2015 Großraming 2016 contents 04 Preface Bern 2015 Fiesole 2015 08 Erasmus+ 10 ECma – Educational program 12 Partnerships 14 Partners 23 Cooperating partners 24 STaTEmEnTs about ECma i 26 Ensembles 29 Alumni 30 Guest Ensembles 31 Awards and achievements Vienna/Grafenegg 2015 41 General assembly, 2015 42 STaTEmEnTs about ECma ii Oslo 2016 44 Tutors 49 Cd releases Manchester 2016 50 Obituary – peter Cropper 52 Events Vilnius 2016 54 The association as of october 2016 EuropEan ChambEr musiC aCadEmy 3 PREFACE – ThE STORY OF ECMA t was piero Farulli who had the original idea and subsequently asked potential how to search for and find their own inter pre tations. The expansion his good friends hatto beyerle (alban berg Quartet), Norbert brainin from string quartets to ensembles with piano or other instruments was a i (amadeus Quartet), and milan skampa (smetana Quartet) to head the natural consequence. first accademia Europea del Quartetto with him in Fiesole. This course, held during 2001 and 2002, was an extraordinary success for the young Today, following more than ten years of excellent work and out standing participants: the incredible experience of spending one week with four great success under the leadership of its two artistic directors, ECma has come artists and masters, each of them so different from the others, was utterly to be regarded as an apex of chamber music training. and a continuously unlike any of the master classes in which they had participated before! increasing number of institutions, academies, and festivals have come to view ECma as an anchor point: not as a standalone school, but as a strate- so piero asked hatto to take the lead and fashion a true programme of ad- gic partnership of institutions, each of which makes its own contribution in vanced training for chamber musicians that would travel throughout Europe. -

Ouvrir La Préface (PDF)

III Vorwort als er in Prag seine frühere Lehrtätig- siehe die Bemerkungen am Ende der vor- keit als Professor für Komposition und liegenden Edi tion). Für beide Komposi- Instrumentation am Konservatorium tionen forderte Dvorák ein erheblich wieder aufnahm. Während der Arbeit höheres Honorar, als es bei ihm zuvor am Quartett op. 105 schrieb er am für Kammermusikwerke üblich war, was Antonín Dvorák (1841 – 1904) war seit 23. Dezember an seinen Freund Alois sowohl den erhöhten Marktwert seiner Herbst 1892 als Musikdirektor am Na- Göbl: „Ich bin jetzt sehr fleißig. Ich Musik als auch sein gestiegenes Selbst- tional Conservatory of Music in New arbeite so leicht und es gelingt mir so bewusstsein unterstreicht. „Das Hono- York tätig. 1895 verbrachte er wie im wohl, daß ich es mir gar nicht besser rar für die 2 Quartette ist à 3000 Mark Jahr zuvor seine Sommerferien in Böh- wünschen könnte. Ich habe soeben mein jedes (= 6000 Mark) gewiß so hoch be- men. Im August entschloss er sich, nicht neues Quartett G-dur beendet und jetzt messen, wie irgend denkbar!“, stöhnte mehr nach Amerika zurückzukehren. beschließe ich schon wieder ein zweites Simrock, akzeptierte die For derung Neben der finanziell angespannten Si- in As-dur, zwei Sätze habe ich ganz fer- aber ohne weitere Verhandlung (Brief tuation des Conservatory waren Heim- tig und das Andante [so die ursprüngli- vom 15. Mai 1896, Korrespondenz und weh und die monatelange Trennung von che Bezeichnung für Satz III] schreibe Dokumente, Bd. 8, Prag 2000, S. 25). seinen Kindern ausschlaggebend für ich gerade und ich denke, ich werde es Vermutlich fand die Uraufführung diese Entscheidung. -

000000018 1.Pdf

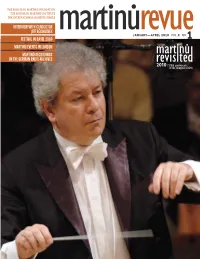

THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ FOUNDATION THE BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ INSTITUTE THE INTERNATIONAL MARTINŮ CIRCLE INTERVIEW WITH CONDUCTOR JIŘÍ BĚLOHLÁVEK martinůJANUARY—APRILrevue 2010 VOL.X NO. FESTIVAL IN BASEL 2009 1 MARTINŮ EVENTS IN LONDON MARTINŮ RECORDINGS ķ IN THE GERMAN RADIO ARCHIVES contents 3 Martinů Revisited Highlights 4 news —Anna Fárová Dies —Zdeněk Mácal’s Gift 5 International Martinů Circle 6 festivals —The Fruit of Diligent and Relentless Activity CHRISTINE FIVIAN 8 interview …with Jiří Bělohlávek ALEŠ BŘEZINA 9 Liturgical Mass in Prague MILAN ČERNÝ 10 News from Polička LUCIE JIRGLOVÁ UP 0121-2 11 special series —List of Martinů’s Works VIII 12 research —Martinů Treasures in the German Radio Archives GREGORY TERIAN 13 review —Martinů in Scotland GREGORY TERIAN 14 review —Czech Festival in London UP 0123-2 UP 0126-2 PATRICK LAMBERT 16 festivals —Bohuslav Martinů Days 2009 PETR VEBER 17 news / conference 18 events 19 news UP 0106-2 UP 0122-2 UP 0116-2 —New CDs, Publications ARCODIVA Jaromírova 48, 128 00 Praha 2, Czech Republic tel.: +420 223 006 934, +420 777 687 797 • fax: +420 223 006 935 e-mail: [email protected] ķ highlights IN 2010 TOO WE ARE CELEBRATING a momentous anniversary – 120 years since the birth of Bohuslav Martinů (8 December 1890, Polička). Numerous ensembles and music organisations have included Martinů works in their 2010 repertoire. We will keep you up to date on this page with the most significant events. MORE INFORMATION > www.martinu.cz > www.czechmusic.org ‹vFESTIVALS—› The 65th Prague Spring The 65th PRAGUE SPRING INTERNATIONAL MUSIC FESTIVAL International Music Festival Prague, 12 May—4 June 2010 Prague / 12 May—4 June 2010 www.festival.cz 15 May 2010, 11.00 am > Martinů Hall, Lichtenštejn Palace Scherzo, H. -

A Survey of Czech Piano Cycles: from Nationalism to Modernism (1877-1930)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM NATIONALISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) Florence Ahn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Larissa Dedova Piano Department The piano music of the Bohemian lands from the Romantic era to post World War I has been largely neglected by pianists and is not frequently heard in public performances. However, given an opportunity, one gains insight into the unique sound of the Czech piano repertoire and its contributions to the Western tradition of piano music. Nationalist Czech composers were inspired by the Bohemian landscape, folklore and historical events, and brought their sentiments to life in their symphonies, operas and chamber works, but little is known about the history of Czech piano literature. The purpose of this project is to demonstrate the unique sentimentality, sensuality and expression in the piano literature of Czech composers whose style can be traced from the solo piano cycles of Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), Josef Suk (1874-1935), Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1935) to Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942). A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM ROMANTICISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) by Florence Ahn Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2018 Advisory Committee: Professor Larissa Dedova, Chair Professor Bradford Gowen Professor Donald Manildi Professor -

CCMA Coleman Competition (1947-2015)

THE COLEMAN COMPETITION The Coleman Board of Directors on April 8, 1946 approved a Los Angeles City College. Three winning groups performed at motion from the executive committee that Coleman should launch the Winners Concert. Alice Coleman Batchelder served as one of a contest for young ensemble players “for the purpose of fostering the judges of the inaugural competition, and wrote in the program: interest in chamber music playing among the young musicians of “The results of our first chamber music Southern California.” Mrs. William Arthur Clark, the chair of the competition have so far exceeded our most inaugural competition, noted that “So far as we are aware, this is sanguine plans that there seems little doubt the first effort that has been made in this country to stimulate, that we will make it an annual event each through public competition, small ensemble chamber music season. When we think that over fifty performance by young people.” players participated in the competition, that Notices for the First Annual Chamber Music Competition went out the groups to which they belonged came to local newspapers in October, announcing that it would be held from widely scattered areas of Southern in Culbertson Hall on the Caltech campus on April 19, 1947. A California and that each ensemble Winners Concert would take place on May 11 at the Pasadena participating gave untold hours to rehearsal Playhouse as part of Pasadena’s Twelfth Annual Spring Music we realize what a wonderful stimulus to Festival sponsored by the Civic Music Association, the Board of chamber music performance and interest it Education, and the Pasadena City Board of Directors. -

Czech Music Culture in London and Post-1989 Developments in Czechoslovakia at the Time

International Journal of Arts and Commerce ISSN 1929-7106 www.ijac.org.uk CZECH MUSIC CULTURE IN LONDON AND POST-1989 DEVELOPMENTS IN CZECHOSLOVAKIA AT THE TIME Markéta Koutná Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci, Filozofická Fakulta, Katedra muzikologie Czech Republic E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The study deals with Czech-London musical relations, particularly Czech music culture in London within the context of cultural, social and political change in 1989. An analysis of the opera, chamber music, and symphonic production of Czech music in London between 1984 and 1994 identifies how and whether the Czechoslovak Velvet Revolution affected the firm position that Czech music culture had held in the capital of the United Kingdom. Key words: Czech musical culture, London, emigration, composers, the Velvet Revolution, 1989 The musical relations between the Czechs and London represent an important current issue. As the capital of the United Kingdom, London naturally takes the lead within the British cultural scene. With its population, budget, and institutional capacities, it is one of the world’s major social and cultural centres, and thanks to the high interest of London-based institutions in Czech music, it is also one of the world's top producers of Czech music. The current research examines how, if at all, the events of November 1989 influenced the position of Czech musical culture in London and the relationship between Czech and London musicians. I became interested in this issue while researching data for my dissertation on Czech musical culture in London.1 Using the specific example of interpretations of Czech opera, chamber music and 1 The study is a part of the student grant project IGA_FF_2015_024 Influence of the Velvet Revolution on Czech Musical Culture in London and all the data used in the study draw on the author’s research for her dissertation Czech Musical Culture in London Between 1984 and 1994. -

CUMULATIVE INDEX: SECTION (A): ARTICLES

CUMULATIVE INDEX to Czech Music and Other Society Journals: 1974-1994 Abstracted by Richard Beith Issue 2 July 1995 INTRODUCTION The Dvořák Society has always published a journal since the Society was founded in 1974. In the early years, the format and title changed frequently, but the name Czech Music has been used since 1978 and the familiar A5 format has been in use since 1980. Journal size has varied from the first issue, a single sheet of foolscap, printed on both sides, to the latest issue with 192 A5 size pages. Up until the Autumn 1987 issue, Czech Music also contained the “current information” listing concert dates, latest record news and forthcoming Society events. Since 1988 the entirely separate Newsletter has been published to cover such “current information”. Ephemeral items such as crosswords, concert announcements and new record issue news are omitted from the index, particularly such information appearing in the Journals prior to 1988, i.e. before the introduction of the separate Newsletter. The titles of articles, as printed, have occasionally been expanded by additional explanations in parenthesis. For example, “Music to Dismember” referring to cuts in live performances of Dvořák’s works now has the added comment: (Performance Cuts). Titles of musical works have generally been left in the language of the original articles, Czech, English or Slovak as appropriate. As the journals have not been given continuous pagination within one volume, i.e., as every separate issue starts with a page 1, a very full reference is given, egg: “March 74 1:1:1” = March 1974 issue, Volume 1, No 1, article starting on page 1; Summer 1993 18:1:87 = Summer 1993 issue, Volume 18, No 1, article starting on page 87. -

Catalogo Per Autori Ed Esecutori

Abel, Carl Friedrich Quartetti, archi, Op. 8, No. 5, la maggiore The Salomon Quartet The Schein String Quartet Addy, Obo Wawshishijay Kronos Quartet Adorno, Theodor Wiesengrund Zwei Stucke fur Strechquartett op. 2 Buchberger Quartett Albert, Eugene : de Quartetti, archi, Op. 7, la minore Sarastro Quartett Quartetti, archi, Op. 11, mi bemolle maggiore Sarastro Quartett Alvarez, Javier Metro Chabacano Cuarteto Latinoamericano 1 Alwyn, William Quartetti, archi, n. 3 Quartet of London Rhapsody for String Quartet Arditti string quartet Andersson, Per Polska fran Hammarsvall, Delsbo The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom Quartet The Skane Quartet Andriessen, Hendrik Il pensiero Raphael Quartet Aperghis, Georges Triangle Carre Trio Le Cercle Apostel, Hans Erich Quartetti, archi, Op. 7 LaSalle Quartet Arenskij, Anton Stepanovic Quartetti, archi, op. 35 Paul Rosenthal, Vl Matthias Maurer, Vla Godfried Hoogeveen, Vlc Nathaniel Rosen, Vlc Arriaga y Balzola, Juan Crisostomo Jacobo Antonio : de Quartetti, archi, No. 1, re minore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Quartetti, archi, No. 2, la maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet 2 Quartetti, archi, Nr. 3, mi bemolle maggiore Voces Streichquartette Quartet sine nomine Rasoumovsky Quartet Atterberg, Kurt Quartetti, archi, Op. 11 The Garaguly Quartet Aulin, Tor Vaggvisa The Follinger-Hedberg Quartet The Galli Quintet The Goteborg Quartet The Halsingborg Quartet The Kjellstrom -

Program Trio in C Major, No

Long Theater * Stockton, California * March 31, 1979 * 8:00 p.m. FRIENDS OF CHAMBER MUSIC in cooperation with UNIVERSITY OF THE PACIFIC, and SAN JOAQUIN DELTA COLLEGE present Bruno Canino, piano Cesare Ferraresi, violin Rocco Filippini, cello PROGRAM TRIO IN C MAJOR, NO. 43 (HOBOKEN XV NO. 27) • (Franz) Joseph Haydn (1732 - 1809) Allegro Andante Finale (Presto) TRIO IN A MINOR (1915) . ... Maurice Ravel Modere (1875 - 1937) Pantoum (Assez vif) Passacaille (Tres large) Final (Anime) INTERMISSION TRIO IN B FLAT MAJOR, OPe 97 •• ..... Ludwig ("The Archduke") van Beethoven Allegro moderado (1770 - 1827) Scherzo (Allegro) Andante cantabile, rna pero con moto (Variations) Allegro moderato - Presto Trio di Milano is represented by Mariedi Anders Artists Manage ment, Inc., 535 El Camino Del Mar, San Francisco, California. The TRIO DI MILANO, composed of three noted and talented musicians, was formed in the spring of 1968. Engaged by the most important Italian musical societies to play at Milan, Torino, Venice, Rome, Florence, Pisa, Genoa, and Padua, the Trio has also performed in Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal and the United States and has been acclaimed with enthu siasm and exceptional success everywhere. CESARE FERRARESI was born at Ferrara in 1918, took his degree for violin at the Verdi Conservatorio of Milan, where he is now Principle Professor. Winner of the Paganini Prize and of the International Compe tition at Geneva, he has now for many years enjoyed an intensely full and busy career as a concert artist. Leader of the Radio Symphony Orchestra (RAI) at Milan and soloist of the "Virtuosi di Roma", he has played at the most important music festivals at Edinburgh, Venice, Vienna, and Salz burg and in the major musical centers of Europe, Japan, and the United States.