Educational Association Children's Library Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educating the Whole Person? the Case of Athens College, 1940-1990

Educating the whole person? The case of Athens College, 1940-1990 Polyanthi Giannakopoulou-Tsigkou Institute of Education, University of London A thesis submitted for the Degree of EdD September 2012 Abstract This thesis is a historical study of the growth and development of Athens College, a primary/secondary educational institution in Greece, during the period 1940-1990. Athens College, a private, non-profit institution, was founded in 1925 as a boys' school aiming to offer education for the whole person. The research explores critically the ways in which historical, political, socio-economic and cultural factors affected the evolution of Athens College during the period 1940-1990 and its impact on students' further studies and careers. This case study seeks to unfold aspects of education in a Greek school, and reach a better understanding of education and factors that affect it and interact with it. A mixed methods approach is used: document analysis, interviews with Athens College alumni and former teachers, analysis of student records providing data related to students' achievements, their family socio-economic 'origins' and their post-Athens College 'destinations'. The study focuses in particular on the learners at the School, and the kinds of learning that took place within this institution over half a century. Athens College, although under the control of a centralised educational system, has resisted the weaknesses of Greek schooling. Seeking to establish educational ideals associated with education of the whole person, excellence, meritocracy and equality of opportunity and embracing progressive curricula and pedagogies, it has been successful in taking its students towards university studies and careers. -

Section Iv. Interdisciplinary Studies and Linguistics Удк 821.14

Сетевой научно-практический журнал ТТАУЧНЫЙ 64 СЕРИЯ Вопросы теоретической и прикладной лингвистики РЕЗУЛЬТАТ SECTION IV. INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES AND LINGUISTICS УДК 821.14 PENELOPE DELTA, Malapani A. RECENTLY DISCOVERED WRITER Athina Malapani Teacher of Classical & Modern Greek Philology, PhD student, MA in Classics National & Kapodistrian University of Athens 26 Mesogeion, Korydallos, 18 121 Athens, Greece E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] STRACT he aim of this article is to present a Greek writer, Penelope Delta. This writer has re Tcently come up in the field of the studies of the Greek literature and, although there are neither many translations of her works in foreign languages nor many theses or disser tations, she was chosen for the great interest for her works. Her books have been read by many generations, so she is considered a classical writer of Modern Greek Literature. The way she uses the Greek language, the unique characters of her heroes that make any child or adolescent identified with them, the understood organization of her material are only a few of the main characteristics and advantages of her texts. It is also of high importance the fact that her books can be read by adults, as they can provide human values, such as love, hope, enjoyment of life, the educational significance of playing, the innocence of the infancy, the adventurous adolescence, even the unemployment, the value of work and justice. Thus, the educative importance of her texts was the main reason for writing this article. As for the structure of the article, at first, it presents a brief biography of the writer. -

Mary Paraskeva, 1882-1951

Mary Paraskeva, 1882-1951 Mary Paraskeva was born on the island of Mykonos in 1882. Her father, Nicolas Gripari, a scion of one of the oldest island families, owned a flourishing grain business based in Odessa, a cosmopolitan Black Sea city with a significant Greek population. The family owned the vast 12,000 hectare estate of Baranovka in the Volynia region of NW Ukraine (now Baranivka, in the oblast of Zhitomir). Apart from thousands of acres of valuable timberland, the estate enclosed a manor house which included the Τower of Maria Walewska, Napoleon’s Polish mistress, as well as the eponymous and then famous porcelain factory. We don’t know exactly when Mary Gripari, as she was then, developed an interest in photography, but it must have been at a relatively early age, most likely before she was twenty. According to family legend, she was first instructed in the use of a camera by her elder brother George. Her youth and adolescence were spent on her father’s estate, by that time a millionaire, consul of Greece and noble of the imperial Russian court. In 1903 she married Nicolas Paraskeva, a significantly older civil engineer living in Alexandria whom she accompanied to Egypt. There she became a part of the Greek and European society of Alexandria and met her lifelong friend Argine Salvagou, younger daughter of the Greek writer Penelope Delta. Delta, who never warmed to her, wrote in her memoirs: “That winter I met the ‘sorceress’, the newly married Mary Paraskeva. She read my palm and predicted that I would go through a spiritual crisis…”. -

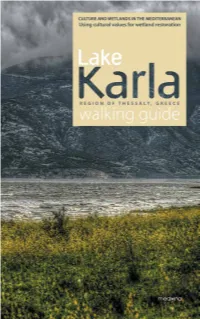

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

What Does Our Country Mean to Us? Gender Justice and the Greek Nation-State

What Does Our Country Mean to Us? Gender Justice and the Greek Nation-State by Athanasia Vouloukos A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © Copyright Athanasia Vouloukos 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 0-494-10075-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 0-494-10075-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Of Greek Feminism

Arms and the Woman Margaret Poulos Interwar Democratisation and the Rise of Equality: The 'First Wave' of Greek Feminism 3.1 Introduction After Parren's pioneering efforts in the late nineteenth century, a new feminism emerged in 1 Greece during the interwar years, which was greater in scale and whose primary focus was the extension of suffrage to women. As such it is often referred to as the 'first wave' of Greek feminism, in line with Anglo-American conceptions of feminist history.1 Interwar feminism emerged in the context of the 'Bourgeois Revolution' of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos— the period of great socio-political and economic transformation between 1909 and 1935,2 during which the territorial gains of the Balkan Wars (1912–13), participation in the Great War, and the massive demographic changes following the catastrophic Asia Minor campaign of 1921–223 were amongst the events of greatest consequence. The ascendancy of liberal politician Eleftherios Venizelos reflected largely a subterranean transformation of the Greek social economy. The struggle for dominance between the increasingly powerful merchant classes or bourgeoisie and the traditional (mainly rural) social classes—represented by the aristocracy, landowners, the peasantry, and the clergy—intensified and culminated in the Revolution of 1909,4 which brought Venizelos to power. As the bourgeoisie's most significant advocate, Venizelos ushered in a new political paradigm in his efforts to create the institutions indispensable to a modern republic, in the place of the traditional system of absolute clientelism that had prevailed since Independence. Amongst his important contributions were legislative reforms and the establishment of institutions that supported the growth of the fledgling industrial economy. -

14 the Language Question and the Diaspora*

14 The Language Question and the Diaspora* Karen Van Dyck The national perspective on the language question The issue of language has a privileged place in Greek intellectual discourse. In America the race question has been at the forefront of political discussions over the past century and a half; Italy has its Southern Question; in Greece it is the Language Question (to glossiko zitima), that has generated an analogous amount of pages and debate. Since the eighteenth century, well before independence, Greek intellectuals, school teachers, and priests have fought over which variety of the Greek language should be the official one: demotic, the language ‘of the people’, or katharevousa, a purist language that reintroduced elements of ancient Greek in order to ‘clean up’, or ‘purify’, spoken Greek, a language supposedly contaminated by centuries of Roman, Frankish, and Turkish rule. Which register of Greek a Greek spoke – and, even more importantly, wrote – was central to what it meant to be Greek. As scholars have amply shown, the language question and the particular problem of diglossia – in the Greek case the existence of two competing varieties of the language – have been enmeshed with the major developments and cultural struggles in modern Greek history from the nation’s inception to the present, as has been discussed by Peter Mackridge in chapter 13.1 Here I propose to shift the focus from the national to a diasporic perspective on the Language Question. I begin by rehearsing the familiar story of language reform * I am grateful to Roderick Beaton, Stathis Gourgouris, Nelson Moe, David Ricks, Dorothea von Mücke, and Clair Wills for their helpful comments, and especially to Peter Mackridge without whose knowledge and generosity this chapter would not have been written. -

Born in Athens in 1958. He Was an Athens School of Fine Arts Student (1979-1985)

Born in Athens in 1958. He was an Athens School of Fine Arts student (1979-1985). Upon graduation he had his first solo show; another ten followed. He has taken part in group exhibitions as well as global events. His works are found in private and public collections in Greece and abroad. He has also illustrated the following books: Anti tis Siopis by Lefteris Poulios (Instead of Silence, 1993), O Afanis Thriamvos Tis Omorfias by Argyris Chionis (The Unseen Triumph of Beauty, 1995), Mikri Zoologia (The Little Book of Zoology, Collective Work, 1998) and I Naftilia Kyklous Kanei by Philippos Begleris (Shipping goes around in circles, 2011). Between 1986 and 1996 he taught free-hand drawing at the Vakalo School of Arts. He lives and works in Athens. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013 Tassos Mantzavinos - Kostas Papanikolaou, Citronne Gallery, Poros, Greece 2012 Tassos Mantzavinos, Theorema Art Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2012 For my strength is made perfect in weakness, Benaki Museum (Pireos str. Annexe), Athens, Greece 2012 Skoufa Gallery, Athens, Greece 2010 Chess, K-art Gallery, Athens, Greece 2010 Zoumboulakis Galleries, Athens, Greece 2010 Angelo and Lito Katakouzenos Foundation, Athens, organised by the Hellenic Folklore Research Centre of the Academy of Athens, Athens, Greece (curated by Louisa Karapidaki) 2008 Galerie Aliquando, Paris, France 2008 TinT Gallery, Thessaloniki, Greece 2005 Ionos Gallery, Karditsa, Greece 2005 Nees Morfes Gallery, Athens, Greece 2004 TinT Gallery, Thessaloniki, Greece 2003 Ariadne Gallery, Heracleion, Crete, Greece -

![Balkanologie, Vol. IX, N° 1-2 | 2005, « Volume IX Numéro 1-2 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 19 Mai 2008, Consulté Le 17 Décembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9873/balkanologie-vol-ix-n%C2%B0-1-2-2005-%C2%AB-volume-ix-num%C3%A9ro-1-2-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-19-mai-2008-consult%C3%A9-le-17-d%C3%A9cembre-2020-4309873.webp)

Balkanologie, Vol. IX, N° 1-2 | 2005, « Volume IX Numéro 1-2 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 19 Mai 2008, Consulté Le 17 Décembre 2020

Balkanologie Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires Vol. IX, n° 1-2 | 2005 Volume IX Numéro 1-2 Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/547 DOI : 10.4000/balkanologie.547 ISSN : 1965-0582 Éditeur Association française d'études sur les Balkans (Afebalk) Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 décembre 2005 ISSN : 1279-7952 Référence électronique Balkanologie, Vol. IX, n° 1-2 | 2005, « Volume IX Numéro 1-2 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 19 mai 2008, consulté le 17 décembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/547 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/balkanologie.547 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 17 décembre 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 SOMMAIRE Dossier : Le meurtre du prêtre dans les Balkans au tourant du XXe siècle Le meurtre du prêtre dans les Balkans au tournant du XXe siècle Bernard Lory Le meurtre du prêtre comme violence inaugurale (Bulgarie 1872, Macédoine 1900) Bernard Lory Preachers of God and martyrs of the Nation The politics of murder in ottoman Macedonia in the early 20th century Basil C. Gounaris Le meurtre du prêtre Acte fondateur de la mobilisation nationaliste albanaise à l'aube de la révolution Jeune Turque Nathalie Clayer Dossier : Diasporas musulmanes balkaniques dans l'Union européenne Diasporas musulmanes balkaniques dans l'Union Européenne Introduction Xavier Bougarel et Dimitrina Mihaylova Western Thracian Muslims in Athens From Economic Migration to Religious Organization Dimitris Antoniou Transmission de l'identité et culte du héros Les associations de -

FRIDTJOF NANSEN and the GREEK REFUGEE PROBLEM1 (September-November 1922)

HARRY J. PSOMIADES FRIDTJOF NANSEN AND THE GREEK REFUGEE PROBLEM1 (September-November 1922) Although the Allied powers had proscribed the newly created League of Nations in Geneva (1919) from being a major player in the shaping of a peace settlement following the defeat of Greek arms in Asia Minor, they were more than eager to have it assume responsibility for a humanitarian crisis for which they were partly culpable. Even before the end of Greek-Turkish hostilities (1919-1922)2 and the signing of the Mudanya armistice in October 1922, they had contemplated calling upon the newly created League of Nations in Geneva (1919) to act as liaison between the Greek and Turkish authorities in matters 1. This work was made possible, in part, by a grant from the Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation; by the support of the director and staff of the League of Nations Archives (Geneva) in 1992; by the director (Dr. Valentini Tselika) and staff of the Benaki Museum Historical Archives, Penelope Delta House (Kifisia); and by the director (Dr. Photini Thomai Constantopoulou) and staff (Michael Mantios) of the Diplomatic and Historical Archives, Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Athens). 2. Following the armistice of Mudros (October 20, 1918), Greek forces occupied Eastern Thrace and in May 1919, at the invitation of the Allies, the Smyrna [Izmir] district. The long delayed and fateful Near East peace treaty of Sèvres (August 20, 1920), not unexpectedly awarded, inter alia, to Greece Eastern Thrace and provided for a zone of Greek influence in the Smyrna region that would eventually lead to Greek annexation. -

The-Greeks-And-The-Making-Review-Kit.Pdf

The story of the Greeks in Egypt from Muhammad Ali to Nasser About the book: From the early nineteenth century through to the 1960s, the Greeks formed the largest, most economically powerful, and geographically and socially diverse of all European communities in Egypt. Although they benefited from the privileges extended to foreigners and the control exercised by Britain, they claimed nonetheless to enjoy a special relationship with Egypt and the Egyptians, and saw themselves as contributors to the country’s modernization. The Greeks and the Making of Modern Egypt is the first account of the modern Greek presence in Egypt from its beginnings during the era of Muhammad Ali to its final days under Nasser. It casts a critical eye on the reality and myths surrounding the complex and ubiquitous Greek community in Egypt by examining the Greeks’ legal status, their relations with the country’s rulers, their interactions with both elite and ordinary Egyptians, their economic activities, their contacts with foreign communities, their ties to their Greek homeland, and their community life, which included a rich and celebrated literary culture. Alexander Kitroeff suggests that although the Greeks’ self-image as contributors to Egypt’s development is exaggerated, there were ways in which they functioned as agents of modernity, albeit from a privileged and protected position. While they never gained the acceptance they sought, the Greeks developed an intense and nostalgic love affair with Egypt after their forced departure in the 1950s and 1960s and resettlement in Greece and farther afield. This rich and engaging history of the Greeks in Egypt in the modern era will appeal to students, scholars, travelers, and general readers alike. -

The Historiography and Cartography of the Macedonian Question

X. The Historiography and Cartography of the Macedonian Question by Basil C. Gounaris 1. The contest for the Ottoman inheritance in Europe From the moment that the word ‘Hellas’ was deemed the most appropriate for the name of the modern state of the Romioi, the question of Macedonia, in theory at least, had been judged. Historical geography – according to Strabo’s well-known commentary – placed the land of Alexander within Greece, but in actuality, of course, the issue did not concern the Greeks directly. Their territorial ambitions extended at a stretch beyond Mt Olympus. Moreover, until the mid-19th century at least, the absence of any rival com- petitors meant that the identity of the Macedonians was not an issue yet. Knowledge of their history in medieval times was foggy, whilst the multilingualism did not surprise anyone: to be an Orthodox Christian was a necessary factor, but also sufficient enough for one to be deemed part of the Greek nation.1 If there was any concern over Macedonia and its inhabitants, then this was clearly to be found within the Slavic world, in particular within the Bulgarian national renais- sance and its relations with both Russia and Serbia. Prior to the foundation of the Greek state in 1822, Vuk Karadjic, the leading Serbian philologist and ethnographer included some Slavic folk songs from Razlog as ‘Bulgarian’ in one of his publications. In 1829 the Ukrainian Yuri Venelin also classed the inhabitants of Macedonia as Bulgarians, in his study The Ancient and Present-Day Bulgarians and their Political, Ethnographic and Religious Relationship to the Russians.