My Thirty Years in Baseball by John J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

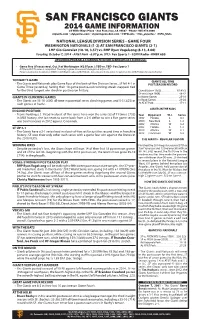

NLDS Notes GM 4.Indd

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2014 GAME INFORMATION 24 Willie Mays Plaza •San Francisco, CA 94107 •Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com •sfgigantes.com •sfgiantspressbox.com •@SFGiants •@los_gigantes• @SFG_Stats NATIONAL LEAGUE DIVISION SERIES - GAME FOUR WASHINGTON NATIONALS (1-2) AT SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS (2-1) LHP Gio Gonzalez (10-10, 3.57) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (8-13, 4.00) Tuesday, October 7, 2014 • AT&T Park • 6:07 p.m. (PT) • Fox Sports 1 • ESPN Radio • KNBR 680 UPCOMING PROBABLE STARTING PITCHERS & BROADCAST SCHEDULE: • Game Five (if necessary), Oct. 9 at Washington (#2:07p.m.): TBD vs. TBD- Fox Sports 1 # If the LAD/STL series is completed, Thursday's game time would change to 5:37p.m. PT Please note all games broadcast on KNBR 680 AM (English radio) and ESPN Radio. All postseason home games broadcast on 860 AM ESPN Deportes (Spanish radio). TONIGHT'S GAME GIANTS ALL-TIME • The Giants and Nationals play Game Four of this best-of- ve Division Series...SF fell 4-1 in POSTSEASON RECORD Game Three yesterday, having their 10-game postseason winning streak snapped, tied for the third-longest win streak in postseason history. Overall (since 1900) . 87-83-2 SF-era (since 1958) . .48-42 GIANTS IN CLINCHING GAMES In Home Games . .25-18 • The Giants are 15-10 (.600) all-time in potential series clinching games and 5-3 (.625) in In Road Games. .23-24 such games at home. At AT&T Park . .17-11 GIANTS IN THE NLDS IN GOOD POSITION • Teams holding a 2-1 lead in a best-of- ve series have won the series 52 of 71 times (.732) Year Opponent W-L Series in MLB history...the last team to come back from a 2-0 de cit to win a ve game series 1997 Florida L 0-3 was San Francisco in 2012 against Cincinnati. -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Baseball Cyclopedia

' Class J^V gG3 Book . L 3 - CoKyiigtit]^?-LLO ^ CORfRIGHT DEPOSIT. The Baseball Cyclopedia By ERNEST J. LANIGAN Price 75c. PUBLISHED BY THE BASEBALL MAGAZINE COMPANY 70 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY BALL PLAYER ART POSTERS FREE WITH A 1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION TO BASEBALL MAGAZINE Handsome Posters in Sepia Brown on Coated Stock P 1% Pp Any 6 Posters with one Yearly Subscription at r KtlL $2.00 (Canada $2.00, Foreign $2.50) if order is sent DiRECT TO OUR OFFICE Group Posters 1921 ''GIANTS," 1921 ''YANKEES" and 1921 PITTSBURGH "PIRATES" 1320 CLEVELAND ''INDIANS'' 1920 BROOKLYN TEAM 1919 CINCINNATI ''REDS" AND "WHITE SOX'' 1917 WHITE SOX—GIANTS 1916 RED SOX—BROOKLYN—PHILLIES 1915 BRAVES-ST. LOUIS (N) CUBS-CINCINNATI—YANKEES- DETROIT—CLEVELAND—ST. LOUIS (A)—CHI. FEDS. INDIVIDUAL POSTERS of the following—25c Each, 6 for 50c, or 12 for $1.00 ALEXANDER CDVELESKIE HERZOG MARANVILLE ROBERTSON SPEAKER BAGBY CRAWFORD HOOPER MARQUARD ROUSH TYLER BAKER DAUBERT HORNSBY MAHY RUCKER VAUGHN BANCROFT DOUGLAS HOYT MAYS RUDOLPH VEACH BARRY DOYLE JAMES McGRAW RUETHER WAGNER BENDER ELLER JENNINGS MgINNIS RUSSILL WAMBSGANSS BURNS EVERS JOHNSON McNALLY RUTH WARD BUSH FABER JONES BOB MEUSEL SCHALK WHEAT CAREY FLETCHER KAUFF "IRISH" MEUSEL SCHAN6 ROSS YOUNG CHANCE FRISCH KELLY MEYERS SCHMIDT CHENEY GARDNER KERR MORAN SCHUPP COBB GOWDY LAJOIE "HY" MYERS SISLER COLLINS GRIMES LEWIS NEHF ELMER SMITH CONNOLLY GROH MACK S. O'NEILL "SHERRY" SMITH COOPER HEILMANN MAILS PLANK SNYDER COUPON BASEBALL MAGAZINE CO., 70 Fifth Ave., New York Gentlemen:—Enclosed is $2.00 (Canadian $2.00, Foreign $2.50) for 1 year's subscription to the BASEBALL MAGAZINE. -

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes

Antitrust and Baseball: Stealing Holmes Kevin McDonald 1. introduction this: It happens every spring. The perennial hopefulness of opening day leads to talk of LEVEL ONE: “Justice Holmes baseball, which these days means the business ruled that baseball was a sport, not a of baseball - dollars and contracts. And business.” whether the latest topic is a labor dispute, al- LEVEL TWO: “Justice Holmes held leged “collusion” by owners, or a franchise that personal services, like sports and considering a move to a new city, you eventu- law and medicine, were not ‘trade or ally find yourself explaining to someone - commerce’ within the meaning of the rather sheepishly - that baseball is “exempt” Sherman Act like manufacturing. That from the antitrust laws. view has been overruled by later In response to the incredulous question cases, but the exemption for baseball (“Just how did that happen?”), the customary remains.” explanation is: “Well, the famous Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. decided that baseball was exempt from the antitrust laws in a case called The truly dogged questioner points out Federal Baseball Club ofBaltimore 1.: National that Holmes retired some time ago. How can we League of Professional Baseball Clubs,‘ and have a baseball exemption now, when the an- it’s still the law.” If the questioner persists by nual salary for any pitcher who can win fifteen asking the basis for the Great Dissenter’s edict, games is approaching the Gross National Prod- the most common responses depend on one’s uct of Guam? You might then explain that the level of antitrust expertise, but usually go like issue was not raised again in the courts until JOURNAL 1998, VOL. -

Landis, Cobb, and the Baseball Hero Ethos, 1917 – 1947

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2020 Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 Lindsay John Bell Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bell, Lindsay John, "Reconstructing baseball's image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947" (2020). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 18066. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/18066 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reconstructing baseball’s image: Landis, Cobb, and the baseball hero ethos, 1917 – 1947 by Lindsay John Bell A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Rural Agricultural Technology and Environmental History Program of Study Committee: Lawrence T. McDonnell, Major Professor James T. Andrews Bonar Hernández Kathleen Hilliard Amy Rutenberg The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this dissertation. The Graduate College will ensure this dissertation is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2020 Copyright © Lindsay John Bell, 2020. All rights reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

This Entire Document

SPORTINGTBADXXAXKED BY THB SFOKTINO LIFE PVB. CO. SNTBSBD AT PHILA. P. O. ASLIFE. SECOND CLASS MATTBB VOLUME 25, NO. 21. PHILADELPHIA, AUGUST 17, 1895. PKICE, TEN CENTS. BRDSH WELL PLEASED MANAGERIAL YIEWS A BIG CUT-DOWN. LATE NEWS BY WIRE. With the Financial Results of This On Mr. Byrne's Position In the Campaign. Temple Cup Matter. Special to "Snorting Life." Special to "Sporting Life." FROM EIGHT CLUBS TO FOUR AT THE O'CONNOR SUIT AGAIHST THE Cincinnati, Aug. 16. The Cincinnati Club Baltimore, Aug. 10. While the Bostons las made more money so far this season were here both Managers Selee and Han- LEAGDE FIZZLES OPT. han any year since the formation of the on talked over the Temple Cup question. ONE SWOOP. resent 12-olub circuit. "Cincinnati is uot Mr. Selee agreed with Ha u Ion that the In- he only city that has done well," said Pres- entlon of the giver of the cup was that dent Brush. "Every city In the League has t should be played for each season by the The Texas-Southern League Loses San Tne California Winter Trip is Assured njoyed increased attendance, and there is rst and second clubs, but Mr. Byrne, who very propspect that it will continue until 9 a member of the Temple Cup Committee, Managerial Views o! the Temple he end of the season. An Improvement in hlnks the club winning the championship Antonio, Honston and Shreveport, he times, together with an increased In- hould play New York for the trophy. The erest In the game by reason of the close Boston manager suggested that as a com- Oasts Austin and Reorganizes as a Cnp Question A Magnate's Optim and exciting race are the causes of this >romise the first and second clubs play a >rosperity." Mr. -

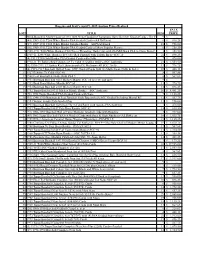

Prices Realized

SPRING 2014 PREMIER AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot# Title Final Price 1 C.1850'S LEMON PEEL STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $2,421.60 2 1880'S FIGURE EIGHT STYLE BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $576.00 3 C.1910 BASEBALL STITCHING MACHINE (NSM COLLECTION) $356.40 4 HONUS WAGNER SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL W/ "FORMER PIRATE" NOTATION (NSM COLLECTION) $1,934.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1909 FORBES FIELD (PITTSBURGH) OPENING GAME AND 5 DEDICATION CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $7,198.80 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO JUNE 30TH, 1910 FORBES FIELD OPENING GAME AND 1909 WORLD 6 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,065.60 1911 CHICAGO CHAMPIONSHIP SERIES (WHITE SOX VS. CUBS) PRESS TICKET AND SCORERS BADGE AND 1911 COMISKEY 7 PARK PASS (NSM COLLECTION) $290.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO MAY 16TH, 1912 FENWAY PARK (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 8 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $10,766.40 ORIGINAL INVITATION AND TICKET TO APRIL 18TH, 1912 NAVIN FIELD (DETROIT) OPENING GAME AND DEDICATION 9 CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $1,837.20 ORIGINAL INVITATION TO AUGUST 18TH, 1915 BRAVES FIELD (BOSTON) OPENING GAME AND 1914 WORLD 10 CHAMPIONSHIP FLAG RAISING CEREMONY (NSM COLLECTION) $939.60 LOT OF (12) 1909-1926 BASEBALL WRITERS ASSOCIATION (BBWAA) PRESS PASSES INCL. 6 SIGNED BY WILLIAM VEECK, 11 SR. (NSM COLLECTION) $580.80 12 C.1918 TY COBB AND HUGH JENNINGS DUAL SIGNED OAL (JOHNSON) BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $11,042.40 13 CY YOUNG SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $42,955.20 1929 CHICAGO CUBS MULTI-SIGNED BASEBALL INCL. ROGERS HORNSBY, HACK WILSON, AND KI KI CUYLER (NSM 14 COLLECTION) $528.00 PHILADELPHIA A'S GREATS; CONNIE MACK, CHIEF BENDER, EARNSHAW, EHMKE AND DYKES SIGNED OAL (HARRIDGE) 15 BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $853.20 16 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED 1948 FIRST EDITION COPY OF "THE BABE RUTH STORY" (NSM COLLECTION) $7,918.80 17 BABE RUTH AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $15,051.60 18 DIZZY DEAN SINGLE SIGNED BASEBALL (NSM COLLECTION) $1,272.00 1944 & 1946 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ST. -

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr. -

Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports

Fordham Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 9 1999 Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Jason M. Pollack Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jason M. Pollack, Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports, 67 Fordham L. Rev. 1645 (1999). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Take My Arbitrator, Please: Commissioner "Best Interests" Disciplinary Authority in Professional Sports Cover Page Footnote I dedicate this Note to Mom and Momma, for their love, support, and Chicken Marsala. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol67/iss4/9 TAKE MY ARBITRATOR, PLEASE: COMMISSIONER "BEST INTERESTS" DISCIPLINARY AUTHORITY IN PROFESSIONAL SPORTS Jason M. Pollack* "[I]f participants and spectators alike cannot assume integrity and fairness, and proceed from there, the contest cannot in its essence exist." A. Bartlett Giamatti - 19871 INTRODUCTION During the first World War, the United States government closed the nation's horsetracks, prompting gamblers to turn their -

Babe Ruth As Legal Hero

Florida State University Law Review Volume 22 Issue 4 Article 13 Spring 1995 Babe Ruth as Legal Hero Robert M. Jarvis Nova University Shepard Broad Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Litigation Commons Recommended Citation Robert M. Jarvis, Babe Ruth as Legal Hero, 22 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 885 (1995) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol22/iss4/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BABE RUTH AS LEGAL HERO* ROBERT M. JARVIS** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................... 885 II. LITIGATION INVOLVING BABE RUTH ........................... 886 III. BABE RUTH'S PLACE IN LEGAL LITERATURE ................ 891 A. JudicialReferences ........................................ 891 B. Scholarly References ...................................... 894 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................................ 896 .I. INTRODUCTION G EORGE Herman Ruth, better known as "Babe" Ruth, "The ~Sultan of Swat," and "The Bambino," generally is recog- nized as the greatest baseball player of all time.' During an illustri- ous career spent playing first for the Boston Red Sox (1914-19), then for the New York Yankees (1920-34), and finally for the Boston Braves (1935), Ruth appeared in 2503 games, belted 714 home runs, collected 2873 hits, knocked in 2211 runs, drew 2056 walks, and re- tired with a .342 batting average and an unparalleled .690 slugging average.2 Incredibly, before his powerful bat dictated moving him from the mound to the outfield, Ruth also compiled a 94-46 won- loss record and a 2.28 earned run average as a pitcher.3 W © 1995 by Robert M.