Level Playing Fields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York

The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and The Politics of New York NEIL J. SULLIVAN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX This page intentionally left blank THE DIAMOND IN THE BRONX yankee stadium and the politics of new york N EIL J. SULLIVAN 1 3 Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogotá Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris São Paolo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available. ISBN 0-19-512360-3 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Carol Murray and In loving memory of Tom Murray This page intentionally left blank Contents acknowledgments ix introduction xi 1 opening day 1 2 tammany baseball 11 3 the crowd 35 4 the ruppert era 57 5 selling the stadium 77 6 the race factor 97 7 cbs and the stadium deal 117 8 the city and its stadium 145 9 the stadium game in new york 163 10 stadium welfare, politics, 179 and the public interest notes 199 index 213 This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgments This idea for this book was the product of countless conversations about baseball and politics with many friends over many years. -

John "Red" Braden Legendary Fort Wayne Semi- Pro Baseball Manager

( Line Drives Volume 18 No. 3 Official Publication of the Northeast Indiana Baseball Association September 2016 •Formerly the Fort Wayne Oldtimer's Baseball Association* the highlight of his illustrious career at that point in John "Red" Braden time but what he could not know was that there was Legendary Fort Wayne Semi- still more to come. 1951 saw the Midwestern United Life Insurance Pro Baseball Manager Co. take over the sponsorship of the team (Lifers). In He Won 5 National and 2 World Titles 1952 it was North American Van Lines who stepped By Don Graham up to the plate as the teams (Vans) sponsor and con While setting up my 1940s and 50s Fort Wayne tinued in Semi-Pro Baseball and Fort Wayne Daisies displays that role at the downtown Allen County Public Library back for three in early August (August thru September) I soon years in realized that my search for an LD article for this all, 1952, edition was all but over. And that it was right there '53 and in front of me. So here 'tis! '54. Bra- A native of Rock Creek Township in Wells Coun dens ball ty where he attended Rock Creek High School and clubs eas participated in both baseball and basketball, John ily made "Red" Braden graduated and soon thereafter was it to the hired by the General Electric Co. Unbeknownst to national him of course was that this would become the first tourna step in a long and storied career of fame, fortune and ment in notoriety, not as a G.E. -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

Base Ball Players

v DEVOTED TO BASE BALL, TRAP SHOOTING AND GENERAL SPORTS Title Registered IB TT. S. Patent Office. Copyright, 1910 by the Sportins LU» Fatttahing Company. Vol. 55-No. 6 Philadelphia, April 16, 1910 Price 5 Cents RACES! The New National oring Base Ball and League President, Predicts the Most Thomas J. Lynch, Successful and Reviews the Con Eventful Season ditions Now Fav- of Record. EW York City, N. Y., April 11. are the rules, and by them the players and On the threshold of the major the public must abidq. All the umpire need* league championship season, to know is the rules, but know them he N Thomas J. Lynch, the new presi must. dent of the National League, yes UMPIRES MUST BE ALERT. terday gave out the first lengthy "The ball players today, with all due »e- < interview of his official career to gpect to the men who played in the past, a special writer of the New York "World," are better as a class. Again, the advent which paper made a big feature of the story. of the college player is responsible. The. President Lynch was quoted as saying: "This brains on the ball field today are not confined is going to be the greatest year in the his to the umpire, but they are to be found be tory of American©s national game. That it neath the caps of every player. No better is the national sport I can prove by a desk- illustration of the keenness of modem ball ful of facts and figures. In the cities where players is to be found than in the game be organized base ball exists 8,000,000 persons tween New York and Chicago, in 1908, that last year paid admissions to see the games. -

Major Leagues Are Enjoying Great Wealth of Star

MAJOR LEAGUES ARE ENJOYING GREAT WEALTH OF STAR FIRST SACKERS : i f !( Major League Leaders at First Base l .422; Hornsby Hit .397 in the National REMARKABLE YEAR ^ AMERICAN. Ken Williams of Browns Is NATIONAL. Daubert and Are BATTlMi. Still Best in Hitting BATTING. Pipp Play-' PUy«,-. club. (1. AB. R.11. HB SB.PC. Player. Club. G. AB. R. H. I1R. SB. PC. Slsler. 8*. 1 182 SCO 124 233 7 47 .422 iit<*- Greatest Game of Cobb. r>et 726 493 89 192 4 111 .389 Home Huns. 105 372 52 !4rt 7 7 .376 Sneaker, Clev. 124 421 8.1 ir,« 11 8 .375 liar foot. St. L. 40 5i if 12 0 0 .375 I'll 11 Lives. JlHTneyt Det 71184 33 67 0 2 .364 Russell, Pitts.. 48 175 43 05 12 .4 .371 l.-llmunn, D«t. 118 474! #2 163 21 8 .338 Konseca, Cln. (14 220 39 79 2 3 .859 Hugh, N. Y 34 84 14 29 0 0 .347.! George Sisler of the Browne is the Stengel, N. V.. 77 226 42 80 6 5 .354 Woo<lati, 43 108 17 37 0 0 H43 121 445 90 157 13 6 .35.4 N. Y Ill 3?9 42 121 1 It .337 leading hitter of the American League 133 544 100 191 3 20 .351 IStfcant. .110 418 52 146 11 5 .349 \ an Glider, St. I.. 4<"» 63 15 28 2 0 .337 with a mark of .422. George has scored SISLER STANDS A I TOP 'i'obln, fit J 188 7.71 114 182 11 A .336 Y 71 190 34 66 1 1 .347 Ftagsloart, Det 87 8! 18 27 8 0 .833 the most runs. -

Christy Mathewson Was a Great Pitcher, a Great Competitor and a Great Soul

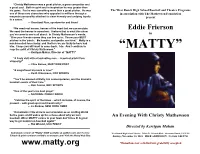

“Christy Mathewson was a great pitcher, a great competitor and a great soul. Both in spirit and in inspiration he was greater than his game. For he was something more than a great pitcher. He was The West Ranch High School Baseball and Theatre Programs one of those rare characters who appealed to millions through a in association with The Mathewson Foundation magnetic personality attached to clean honesty and undying loyalty present to a cause.” — Grantland Rice, sportswriter and friend “We need real heroes, heroes of the heart that we can emulate. Eddie Frierson We need the heroes in ourselves. I believe that is what this show you’ve come to see is all about. In Christy Mathewson’s words, in “Give your friends names they can live up to. Throw your BEST pitches in the ‘pinch.’ Be humble, and gentle, and kind.” Matty is a much-needed force today, and I believe we are lucky to have had him. I hope you will want to come back. I do. And I continue to reap the spirit of Christy Mathewson.” “MATTY” — Kerrigan Mahan, Director of “MATTY” “A lively visit with a fascinating man ... A perfect pitch! Pure virtuosity!” — Clive Barnes, NEW YORK POST “A magnificent trip back in time!” — Keith Olbermann, FOX SPORTS “You’ll be amazed at Matty, his contemporaries, and the dramatic baseball events of their time.” — Bob Costas, NBC SPORTS “One of the year’s ten best plays!” — NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO “Catches the spirit of the times -- which includes, of course, the present -- with great spirit and theatricality!” -– Ira Berkow, NEW YORK TIMES “Remarkable! This show is as memorable as an exciting World Series game and it wakes up the echoes about why we love An Evening With Christy Mathewson baseball. -

2020 MLB Ump Media Guide

the 2020 Umpire media gUide Major League Baseball and its 30 Clubs remember longtime umpires Chuck Meriwether (left) and Eric Cooper (right), who both passed away last October. During his 23-year career, Meriwether umpired over 2,500 regular season games in addition to 49 Postseason games, including eight World Series contests, and two All-Star Games. Cooper worked over 2,800 regular season games during his 24-year career and was on the feld for 70 Postseason games, including seven Fall Classic games, and one Midsummer Classic. The 2020 Major League Baseball Umpire Guide was published by the MLB Communications Department. EditEd by: Michael Teevan and Donald Muller, MLB Communications. Editorial assistance provided by: Paul Koehler. Special thanks to the MLB Umpiring Department; the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; and the late David Vincent of Retrosheet.org. Photo Credits: Getty Images Sport, MLB Photos via Getty Images Sport, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Copyright © 2020, the offiCe of the Commissioner of BaseBall 1 taBle of Contents MLB Executive Biographies ...................................................................................................... 3 Pronunciation Guide for Major League Umpires .................................................................. 8 MLB Umpire Observers ..........................................................................................................12 Umps Care Charities .................................................................................................................14 -

GILIRE's ORDER Cut One In

10 TIIF MORNING OREGONIAN. MONDAY. MARCII ,2, 1914. the $509 and the receipts, according to their fthev touched him fnr k!t hltw and five name straightened out and made standing the end of the tourney. runs. usual announcement. it House, a pitcher from the NOT FOR ' "Rehg battiug for Adams." CLEAN BASEBALL HARD SWIM FATAL E IS HOLDOUT; ...recruited BERGER ' 11-- Central Association, twirled the fifth, "That is another boot you have OREGOMAS BEAT ZEBRAS, 3 sixth and seventh innings and Kills made Ump. I am going to get a hit Johnson, from the Racine, Wis., club, for myself," said Rehg. He made Gene Rich, .Playing "Star Game for the last two. Johnson is a giant, with good his threat with a single. CAViLL FIXED a world of speed. He fanned six of SERAPHS, IS REPORT Last year he pulled one at the ex- GILIRE'S ORDER TO ARTHUR J JUMP PRICE Winners; injured. the seven batters who faced him. pense of George McBrlde, that at first was an- made the brilliant shortstop sore, and The fourth straight victory PLEASANTON, Cal., March 1. (Spe- then on second thought made him nexed by --the Oregonia Club basketball cial.) Manager' Devlin, of th6 Oaks, laugh. Rehg was coaching at third, team against the Zebras yesterday. The was kept busy today, taking part in when an unusually difficult grounder winners scored 11 points-t- the Zebras' the first practice game of the training Angel was hit to MBride's right. Off with Ex-Wor- 3. was played on the Jew- Shortpatcher Is Federal President Says That ld; in The match First Baseman Asks $30,000 ' assembling Former. -

An Analysis of the American Outdoor Sport Facility: Developing an Ideal Type on the Evolution of Professional Baseball and Football Structures

AN ANALYSIS OF THE AMERICAN OUTDOOR SPORT FACILITY: DEVELOPING AN IDEAL TYPE ON THE EVOLUTION OF PROFESSIONAL BASEBALL AND FOOTBALL STRUCTURES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chad S. Seifried, B.S., M.Ed. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Donna Pastore, Advisor Professor Melvin Adelman _________________________________ Professor Janet Fink Advisor College of Education Copyright by Chad Seifried 2005 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to analyze the physical layout of the American baseball and football professional sport facility from 1850 to present and design an ideal-type appropriate for its evolution. Specifically, this study attempts to establish a logical expansion and adaptation of Bale’s Four-Stage Ideal-type on the Evolution of the Modern English Soccer Stadium appropriate for the history of professional baseball and football and that predicts future changes in American sport facilities. In essence, it is the author’s intention to provide a more coherent and comprehensive account of the evolving professional baseball and football sport facility and where it appears to be headed. This investigation concludes eight stages exist concerning the evolution of the professional baseball and football sport facility. Stages one through four primarily appeared before the beginning of the 20th century and existed as temporary structures which were small and cheaply built. Stages five and six materialize as the first permanent professional baseball and football facilities. Stage seven surfaces as a multi-purpose facility which attempted to accommodate both professional football and baseball equally. -

Golf Goods Paramount and Whippet Golf Balls And

OSVOtCO TO Sportsmen anZ Athletes Base Ball, Trap Shooting Hunting, Fishing. College Foot Ball, Golf. Laivn Tennis. Cricket, Track Athletics, Vasket Ball, Sorter. Court snnif. Billiards, Bowling, Rifle and Revolver Shooting, Automobtlmg. Yachting. Camping, Rowing, Canoeing, Motor Boating, Swimming, Motor Cycling, Polo, Harness Racing and Kennel. VOL. 67. NO, 21 PHILADELPHIA. JULY 22,1916 PRICE 5 CENTS illp:':":::;:-::>::>: George men are chased from the game, probably suspended, IN SHORT METRE when they have a righteous kick. For instance, it looked like bad judgment on the part of Bill Klem to ANAGER FIELDKR JONES, of the Browns, is chase Zimmerman last Tuesday,-as 7Am had a right M one of those veterans who thinks the game is not porting Hilt to talk and argue with the umpire, as he is captain played as intelligently as it formerly was: He said: A WEEBTLT JOUBNAL DEVOTED TO BABB BALL, TRAP of the Cubs. Tet a lot of fellows have been pulling "I have not seen many of the plays which formerly rough stuff, and just because they are stars have been \vere used by winning major league teams. They seem SHOOTING AND ALL CLEAN SFOBTS. getting away with it. Ty Cobb was fined ^25 and to have been forgotten or relegated by the order of *HB WORLD'S OLDEST AND BEST BASB BALL JODKNAL. suspended three days for pulling a stunt that should things. The hitting nowadays is not as strong as it have banned him for a month, without pay, yet maybe used to be in the old days, when the pitchers were ZOTTNDED APRIL, 1SS3 a captain or manager will be soaked just as much as just as good as they are today, and in many instances Cobb for arguing with the umpire over a decision that better. -

1826 CHESTNUT ST Name of Resource: Aldine Theatre Proposed

ADDRESS: 1826 CHESTNUT ST Name of Resource: Aldine Theatre Proposed Action: Designation Property Owner: Sam’s Place Realty Associates LP Nominator: Kevin Block, Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia Staff Contact: Laura DiPasquale, [email protected] OVERVIEW: This nomination proposes to designate the property at 1826 Chestnut Street as historic and list it on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The nomination contends that the former Aldine Theatre, constructed in 1921, is significant under Criteria for Designation A, E, and J. Under Criterion A, the nomination argues that the theatre has significant character, interest, or value as one of the last remaining first-run movie palaces in Philadelphia. Under Criterion E, the nomination explains that the Aldine was the work of prominent local builders William Steele & Sons. Under Criterion J, the nomination argues that the Aldine represents the commercial development of Chestnut Street in the prestigious Rittenhouse Square neighborhood after the turn of the twentieth century. Following the submission of the nomination and notification to the property owner, the nominator uncovered additional information not presented in the nomination, which is posted on the Historical Commission’s website as additional information. The Committee on Historic Designation previously reviewed a nomination for the property in March 1986 and recommended against designation owing to the loss of architectural integrity of the interior and the front doors. The Historical Commission adopted the recommendation of the Committee at its April 1986 meeting and declined to designate the property. The staff notes that the interior of the property is not under consideration, and that the Historical Commission routinely designates properties that have alterations. -

LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE* 1 1909 E102 Anonymous Christy Mat(T)

Huggins and Scott's December 12, 2013 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE* 1 1909 E102 Anonymous Christy Mat(t)hewson PSA 6 17 $ 5,925.00 2 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Bat Off Shoulder) with Piedmont Factory 42 Back—SGC 60 17 $ 5,628.75 3 Circa 1892 Krebs vs. Ft. Smith Team Cabinet (Joe McGinnity on Team) SGC 20 29 $ 2,607.00 4 1887 N690 Kalamazoo Bats Smiling Al Maul SGC 30 8 $ 1,540.50 5 1914 T222 Fatima Cigarettes Rube Marquard SGC 40 11 $ 711.00 6 1916 Tango Eggs Hal Chase PSA 7--None Better 9 $ 533.25 7 1887 Buchner Gold Coin Tim Keefe (Ball Out of Hand) SGC 30 4 $ 272.55 8 1905 Philadelphia Athletics Team Postcard SGC 50 8 $ 503.63 9 1909-16 PC758 Max Stein Postcards Buck Weaver SGC 40--Highest Graded 12 $ 651.75 10 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder Ty Cobb/Desperate Slide for Third PSA 3 11 $ 592.50 11 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Cleveland Americans PSA 5 with Joe Jackson 9 $ 1,303.50 12 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Brooklyn Nationals PSA 5 7 $ 385.13 13 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card St. Louis Nationals PSA 4 5 $ 474.00 14 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Boston Americans PSA 3 2 $ 325.88 15 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card New York Nationals PSA 2.5 with Thorpe 5 $ 296.25 16 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Pittsburgh Nationals PSA 2.5 13 $ 474.00 17 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Detroit Americans PSA 2 16 $ 592.50 18 1913 T200 Fatima Team Card Boston Nationals PSA 1.5 7 $ 651.75 19 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards of Philadelphia & Pittsburgh Nationals--Both PSA 6 $ 272.55 20 (4) 1913 T200 Fatima Team Cards--All PSA 2.5 to 3 11 $ 770.25